15. When Installation Art Depends on Live Surroundings to Survive

- Camilla Ayla Oliveira dos Anjos

- Magali Melleu Sehn

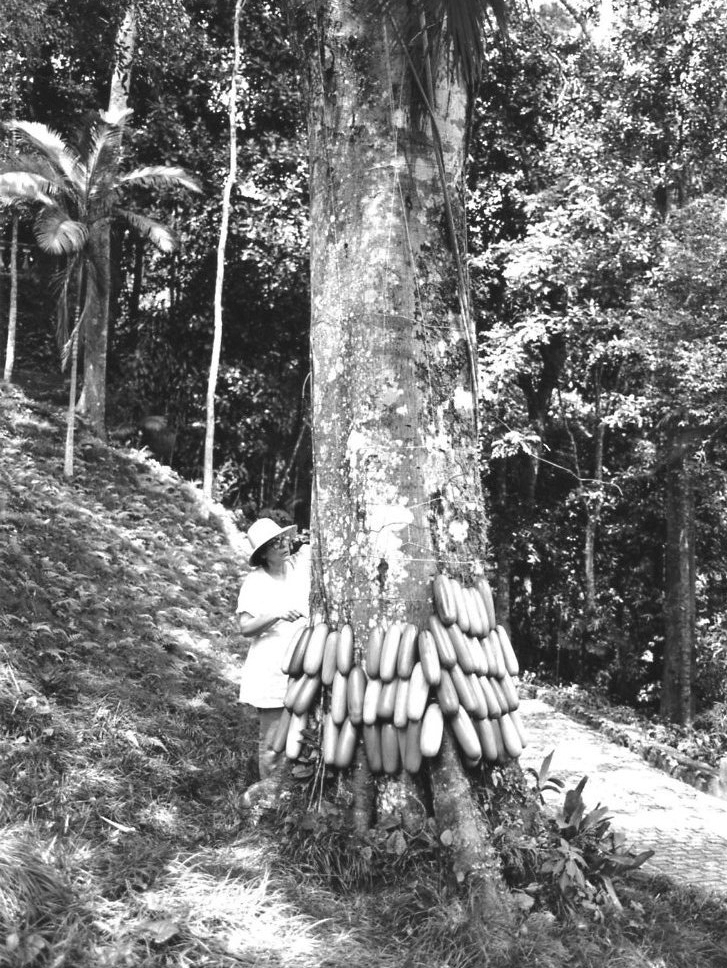

Although living matter in art is often associated with rapid decay, the artwork discussed here, Aqui Estão (Here They Are, 1999, fig. 15.1) by Anna Maria Maiolino (b. 1942), is made from a material that is organic yet relatively stable: wood. The living matter that supports the existence of this artwork is the tree to which it is attached. For this installation, the natural surrounding is as important as the wood sculpted by the artist’s hand.

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1The Museu do Açude in Rio de Janeiro is a historic museum founded by Raymundo Ottoni Castro Maya (1894–1968) using property and money that he acquired through his family’s lucrative coffee business, with a collection primarily composed of objects collected in Brazil and during his travels across the world.1 Castro Maya was an important patron of the arts in Rio de Janeiro in the mid-twentieth century. The museum was inaugurated during his lifetime, in 1964, and until the 1990s was focused on its historical collection. In 1983 the Castro Maya Foundation ceased to exist and the museum became federal property when the estate transferred the responsibility for its administration to the Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional.

What sets the Museu do Açude apart from other historical institutions is its location in one of the largest national parks inside a huge urban area in Brazil: the Tijuca Forest.2 In the 1990s, increased awareness of the importance of the surrounding natural space prompted the director of the museum at the time, Carlos Martins, along with the artist Tunga, to invite artists to submit proposals for site-specific installations within the forest. In 1993 the first such, entitled Aquadorado, was realized by Shelagh Wakely: Wakely sprinkled a thin layer of powdered gold in the waters of one of the museum’s outdoor fountains. After this first experience with contemporary art outdoors, Martins decided to host an exhibition called Potências do Orgânico (Organic Potencies) in 1994 consisting entirely of temporary site-specific installations, curated by Marcio Doctors. Some of the installations were meant to decay and eventually disappear; for example, Tunga created an art installation using tables covered in syrup and a UV light to attract insects, which became incorporated into the installation. Artur Barrio wrapped a gate in raw meat.

Following this first outdoor exhibition, the new museum director, Vera de Alencar, implemented a project for the occupation of the museum’s forest space with permanent, site-specific installations. Called Espaço de instalações permanentes (Space of Permanent Installations), it was inaugurated with two works: Anna Maria Maiolino’s Aqui Estão (Here They Are) and Iole de Freitas’s Dora Maar na Piscina (Dora Maar in the Pool). This collection eventually grew to include ten works by different artists and was renamed Circuito de Arte Contemporânea (Contemporary Art Track). The most recent additions came in 2016. Since 2013 the museum has also hosted annual temporary exhibitions of site-specific works in its outdoor spaces.

Aqui Estão

Aqui Estão is one in a series of works exploring composition, material, and gesture initiated by Anna Maria Maiolino in the beginning of the 1990s. The manufacturing by Maiolino’s hand (fig. 15.2) is as important as the aesthetic result. The repetition of the same gesture created “primitive forms,” which look alike but are never exactly the same (, 32). The gesture imprints a singularity in each one (fig. 15.3). The art critic Suely Rolnik regards Aqui Estão as the climax of this series:

Solid cylinders with rounded ends made from a variety of wood shaped on a lathe, providing a rich range of colors, shades and nuances. The forms are linked by a metal wire that goes through a hole made at one end and binds them to the trunk of an ancestral tree in its natural forest habitat. The work establishes a living composition comprised in the natural trunk and its exuberant cloak of artificial fruit. In this intimate contact, the woods of the artwork evolve with the natural changes in the wood of the trunk; exposed to the same milieu, they are again covered with moss and take on the textures and colors of the trees they originally came from. (, 110–11)

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2 Figure 15.3

Figure 15.3Maiolino notes that she chose wood because it would last longer than the unfired clay she had been using thus far in the series. She selected five kinds of wood, made 750 basic forms, and tied them to a huge tree beside the main structure of the Museu do Açude (fig. 15.4). The installation was specifically created for that spot, and only exists as long as the tree and all the cylinders are there. The following passage is from the only known extant interview about the work. Conducted by the curator at the Museus Castro Maya (the parent organization), it has since 2003 played continuously in the Museu do Açude’s reception area:

I don’t mean to compete with nature but clearly nature is powerful—it contains the elements, the wind, the storms. In other words, the artwork should be something to stay there. At the same time, I want to cherish a concept that I have been developing for a long time and is still important to me: it is about repetition, about the gesture in the action of basic forms in repetition. Then I thought about using wood. Then I produced almost eight hundred wood cylinders, shaped them on a lathe, with different kinds of wood, I mean, the idea was to return the matter to the original matter, right? I felt that the artwork’s power takes place from an accumulation, right?! In addition, this installation produces these basic handmade forms, rescuing the idea of a collective labor, those forgotten ideas, and those gestures—not those forgotten ideas—those forgotten gestures. Then the people regain themselves in their labor. The point about the accumulation is that the more time stretches, with more accumulation, the more powerful the artwork is.3

Figure 15.4

Figure 15.4In the exhibition catalogue, Doctors, the curator, also underlines the importance of the installation’s color nuances:

Those who saw the locale before the work was placed in it probably remember it as a neutral space, a space to pass through. Now, what becomes evident is the chromatic explosion of this space, which has been unleashed by the richness of the tones of the wood into many nuances of greens and yellows. Aqui Estão draws us close to the landscape (illusory representation) to usher in an experience of the immanence of this space (installation). (, 52)

Artist Intent Modification: Color Appearance versus Material Decay

Aqui Estão was initially meant to decay. With the passing of time, it would increasingly blend in with nature to the point that it might no longer, at first glance, be recognizable as an artwork made by human hands. Microbiological attacks and patination would cause the wood to lose its rich nuances of color and blend with the tree that supports it. But the museum staff reported that Maiolino changed her mind when she realized that the alterations brought about by gradual deterioration were not going the way she had imagined (the only documentation for this is the oral testimony of former museum staff). Apparently the artist once visited and disliked the visual aspect of her installation so much that she requested a restoration. The artwork was restored around 2014, but again the documentation is very scarce, and consists only of staff recollections and a few digital images.

Two pictures show the process of detachment of the wood pieces from the tree and their reinstallation, but there is no image of the whole work and no documentation of the installation’s condition or the reasons why the restoration was done. Two additional pictures are known, depicting what appears to be the application of a coating, but no one on staff was able to provide information on what precisely they show. One after-treatment picture was found as well, showing just one side of the installation.

The photos and information on the installation’s inauguration in the exhibition catalogue constitute most of the accessible documentation (). The Açude has not maintained any records of the installation’s history besides the images described above.

Risk Management: A Tool to Identify Priorities

The decision-making model for the conservation and restoration of modern and contemporary art proposed by the Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (SBMK) in 1999 and recently revised was initially suggested for Aqui Estão, but could not be practically applied because of the lack of documentation on the work, which is a prerequisite for the model.4 Instead, the risk management process (ABC method) was used, as it had successfully been applied to another indoor installation (; ). Because there was no data about how the installation had interacted with its surroundings, the model was deemed generative of more potential approaches to its conservation. The following steps were followed for evaluating the artwork and its associated risks and future status.

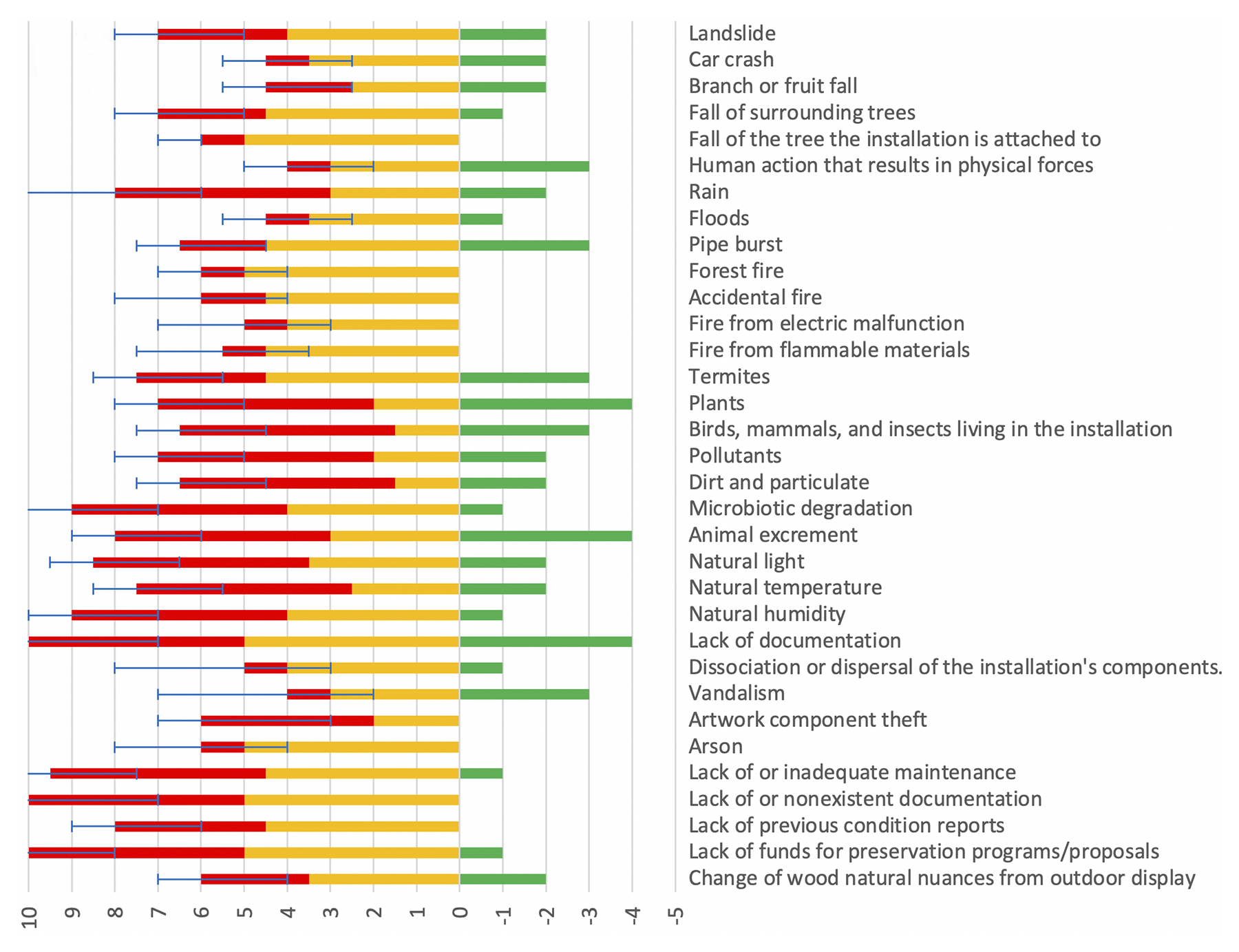

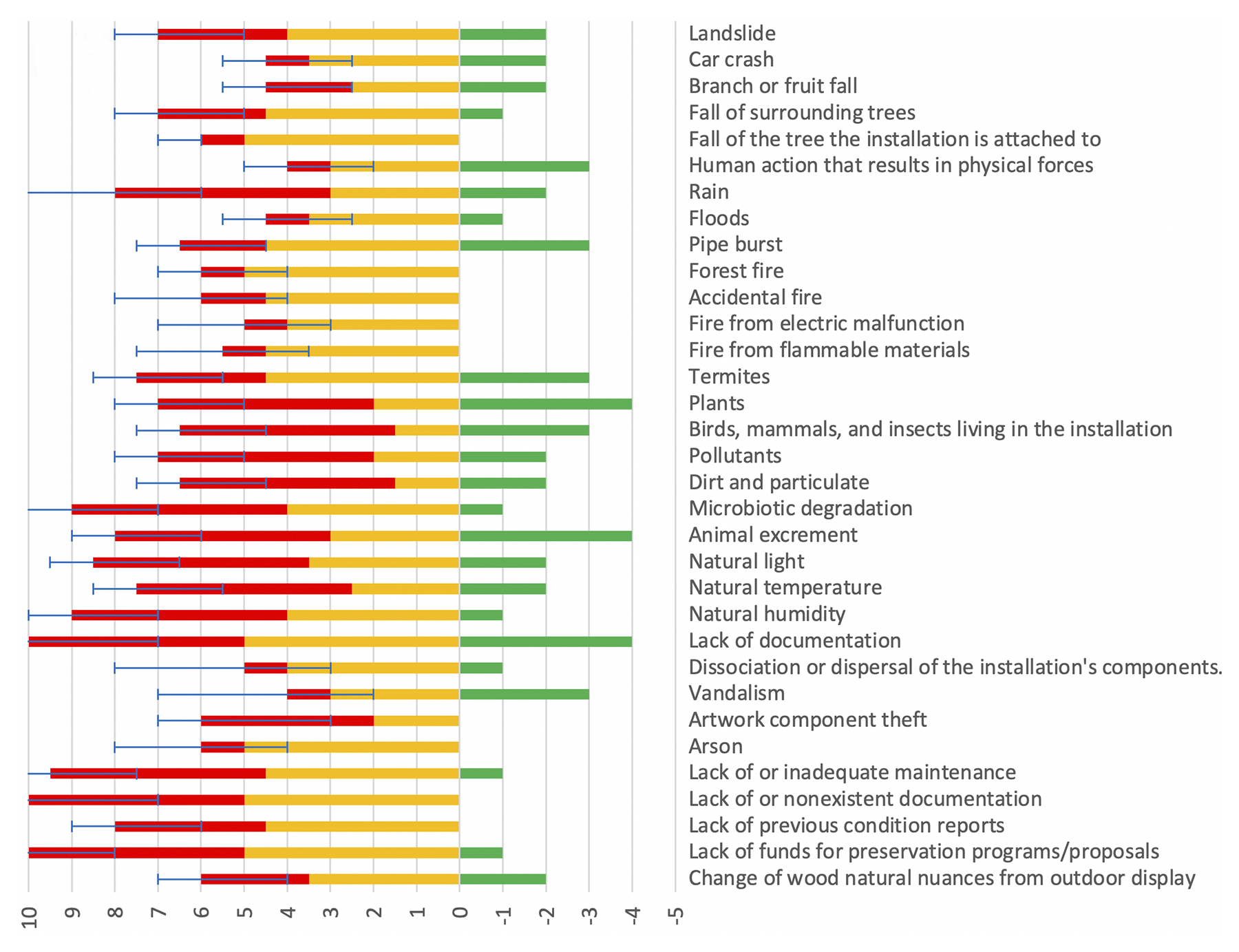

Thirty-three primary risks were enumerated in the evaluation and used to generate table 15.1. The red bars represent the A score (risk probability or damage accumulation), the yellow bars represent the B score (risk impact in the installation), and the green bars represent the C score (chances for reversing the damage). The blue lines represent the uncertainty.

| Risk Type | C Score | B Score | A Score | Uncertain Positive | Uncertain Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landslide | -2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Car Crash | -2 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Branch or fruit fall | -2 | 2.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Fall of surrounding trees | -1 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 2 |

| Fall of the tree the installation is attached to | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Human action that results in physical forces | -3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Rain | -2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Floods | -1 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Pipe burst | -3 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Forest fire | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Acidental fire | 0 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Fire from electric malfunction | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Fire from flammable materials | 0 | 4.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Termites | -3 | 4.5 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Plants | -4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Birds, mammals, and insects living in the installation | -3 | 1.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Pollutants | -2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Dirt and particulate | -2 | 1.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Mircobiotic degradation | -1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Animal excrement | -4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Natural light | -2 | 3.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Natural temperature | -2 | 2.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Natural humidity | -1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Lack of documentation | -4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Dissociation or dispersal of the installation’s components (wood rolls) | -1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Vandalism | -3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Artwork component theft | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Arson | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Lack of or inadequate maintenance | -1 | 4.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Lack of or nonexistent documentation | 0 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Lack of previous condition reports | 0 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1 | 2 |

| Lack of funds for preservation programs/proposals | -1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Change of wood natural nuances from outdoor display | -2 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 2 |

| |||||

| Risk Type | C Score | B Score | A Score | Uncertain Positive | Uncertain Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landslide | -2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Car Crash | -2 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Branch or fruit fall | -2 | 2.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Fall of surrounding trees | -1 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 2 |

| Fall of the tree the installation is attached to | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Human action that results in physical forces | -3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Rain | -2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Floods | -1 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Pipe burst | -3 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Forest fire | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Acidental fire | 0 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Fire from electric malfunction | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Fire from flammable materials | 0 | 4.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Termites | -3 | 4.5 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Plants | -4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Birds, mammals, and insects living in the installation | -3 | 1.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Pollutants | -2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Dirt and particulate | -2 | 1.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Mircobiotic degradation | -1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Animal excrement | -4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Natural light | -2 | 3.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Natural temperature | -2 | 2.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Natural humidity | -1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Lack of documentation | -4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Dissociation or dispersal of the installation’s components (wood rolls) | -1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Vandalism | -3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Artwork component theft | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Arson | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Lack of or inadequate maintenance | -1 | 4.5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Lack of or nonexistent documentation | 0 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Lack of previous condition reports | 0 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1 | 2 |

| Lack of funds for preservation programs/proposals | -1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Change of wood natural nuances from outdoor display | -2 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 2 |

| |||||

Some of the main considerations in an application of risk management were the importance of the color nuances for the artist and critics, as discussed above; the manufacturing by the artist’s hand as an important aspect of the concept; that the installation is site specific and tied to actual living matter; its location, in the sense of both being outdoors and in this specific geographic site; the interaction of the materials and the environment over time; the work’s current conservation status; and any possible link between present damage and possible causes. Information to identify possible problems was drawn in part from the media (news and digital archives from magazines, and other images and information from secondary sources on the internet with specific dates associated) and past museum publications.

The major risks are linked to the geographic location of the Açude and its administration. The seasonal rains—and their physical force—had destroyed two site-specific installations in the past, and damaged the museum buildings themselves. Besides that, the museum suffers from a lack of funding and staff, which is in great part responsible for the absence of documentation and monitoring. The scarcity of planning and funds leads to delayed responses toward conservation, which in this case had led to the loss of important material and immaterial characteristics.

The location outdoors is the major cause of damage to Aqui Estão, yet nothing can be done about that: the work is site specific and impossible to relocate, and its environment cannot be modified. The forest, as a national park, cannot be altered in any way, and the installations will therefore suffer daily the consequences of being outdoors. As a result, the most immediate, urgent, and cheap preservation measure that can be taken is to adequately document the work.

Conservation Proposal: Model for Documentation and Preservation

Since the institution’s documentation is not sufficient to evaluate the alterations that Aqui Estão has already undergone, and given that these same changes cannot be ignored as part of the installation’s history, a model of documentation is proposed that should remedy some lack of information. Models presented in publications from Getty (; ; ; ; ; ), Tate (), the University of Amsterdam (, 179–90, 191–95), and the publications Modern Art: Who Cares? () and Inside Installations () exemplify this suggestion of documentation. The model presented here is the first step for preserving the installation. A model file for documentation of the museum’s site-specific installations that integrates the contemporary outdoor collection was proposed. To make this model, already-revised reports systems in relevant contemporary collections were used.

Since the museum already possesses valuable (albeit unorganized) documentation, mostly photographs and information in exhibition catalogues, the main goal for the initial phase is to organize this information and combine it with additional sources such as artist interviews and newspaper clippings. At the same time, we propose to give the museum staff tools and methods to complete the information bank. Hopefully, compiling the existing information will also encourage the museum to study the various installations’ surroundings and how nature is impacting their preservation.

Once the first steps of the documentation are completed, an interview in situ should be conducted to ask the artist detailed questions about her intentions for the creation of the work and its appearance, and her wishes for its preservation. This should serve as the base to design a conservation plan. It would also be important to create an institutional memory by recording oral histories with staff who were working at the museum when the artwork was created.

The documentation is the most urgent measure because it is the tool and guide when any preservation measure is necessary. The conservation and restoration measures need financial resources to be completed, and one way to obtain these is by presenting the government with a proposal. It is impossible to demonstrate any urgency about these measures if there are no records of the material damage, its rate of occurrence, and by what standards it should be preserved. Having consistent documentation is necessary to show what should be done and how to do it, and obtain the necessary financing. The model file could then be applied to all of the Açude’s outdoor site-specific installations.

With the record of the artist’s current opinion about how the installation should look, a path for preservation in consonance with its material and immaterial aspects can be drawn. Even if the artist decides to accept the material’s decay, the documentation will still be paramount as a way to record its existence—how it has passed through the years and eventually dissolved back into nature.

If instead a decision is taken to mitigate the damage of time, different actions are suggested. First, a study of the microorganisms present on the wood’s surface would be useful to eliminate them in a targeted way. The wooden cylinders would need to be detached from the tree, with adequate documentation of the process and mapping of the cylinders’ positions. The treatment of the wood should include cleaning and removing microbiological attack, consolidating the wood, and filling losses and retouching surfaces as necessary. Most importantly, a protective surface coating should be applied. Finally, the cylinders would be reattached to the tree with a material that does not degrade the artwork, damage the tree, or impede the tree’s continued growth. It would be important, after the restoration, to create a maintenance routine, including periodic application of a biocide and regular monitoring of the artwork’s appearance.

Conclusion

The main threat to Aqui Estão is its location outdoors, yet the work is site specific. In establishing a conservation plan, it is paramount to start by clarifying the artist’s position in regard to the acceptability of decay. Two main pathways are envisaged: one where the work is allowed to decay and slowly disappear, and one in which the wood is treated and its color nuances restored. In both cases, systematic documentation is needed. But the economic reality of the Museus Castro Maya and its overall priorities also must be taken into consideration. There are more than ten thousand items in the collection, and the Açude has only four staff responsible for all its works, both indoors and outdoors.

Unfortunately, considering the resources needed to preserve the site-specific outdoor installations on the one hand, and the pressing needs of the entire collection on the other, one realizes that there is little chance of being able to address the conservation of the outdoor installations. Funding is needed to implement any preservation measures, and the reality of federal museums in Brazil has been, for a long time, one of a lack of funds. This tendency has been worsening in recent years, but we can only hope that the trend will be reversed in the future.

Notes

“Castro Maya was the son of Raymundo de Castro Maya, a renowned engineer with connections to Emperor D. Pedro II, and Theodozia Ottoni de Castro Maya, heiress of a traditional liberal intellectual family. From his father, Castro Maya inherited the taste for collections of art objects, and from his mother, the fondness for literature. The family lived in France when his father occupied the position of Brazilian vice consul in Paris, a city to which Castro Maya returned several times, and which influenced his cultural formation.” From the museum’s website: http://museuscastromaya.com.br/castro-maya/?lang=en. ↩︎

The Tijuca Forest is a mountainous place covered with human-made reforestation. What was once a natural forest had been devastated during colonial times to grow sugar and coffee. Replanting was initiated in the second half of the nineteenth century in part to protect Rio’s water supply, and in part by order of the Portuguese Royal Family, who moved to Rio de Janeiro in the nineteenth century and ordered a wholesale redesign of the city along European lines. They hired landscapers and other professionals to enact the transformation from a coffee plantation to a tropical European-inspired forest. In 1961 Tijuca Forest was declared a national park. It contains most of the city’s natural and human-made attractions, such as the sculpture of Christ the Redeemer atop Corcovado mountain; Mayrink Chapel, decorated with murals painted by Cândido Portinari; and imperial-era constructions such as the pagoda-style gazebo at Vista Chinesa outlook. Other attractions include natural heritage such as the Cascatinha Waterfall and a colossal granite picnic table called Mesa do Imperador (Imperator’s Table). ↩︎

My transcript and translation. The recording in the original Portuguese is available here: https://vimeo.com/125530548. ↩︎

The decision-making model is available at https://sbmk.nl/source/documents/decision-making-model.pdf. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Ankersmit et al. 2011

- Ankersmit, Bart, Agnes W. Brokerhof, Tatja Scholte, Simone Vermaat, and Gaby Wijers. 2011. “Installation Art Subjected to Risk Assessment: Jeffrey Shaw’s Revolution as Case Study.” In Inside Installations: Theory and Practice in the Care of Complex Artworks, edited by Tatja Scholte and Glenn Wharton, 91–101. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Beekens and Learner 2014

- Beekens, Lydia, and Tom Learner, eds. 2014. Conserving Outdoor Painted Sculpture. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Doctors 1999

- Doctors, Marcio, ed. 1999. A forma na floresta: Espaço de instalações permanentes: Iole de Freitas, outubro, 1999: Anna Maria Maiolino, novembro, 1999. Rio de Janeiro: Museu do Açude.

- Heuman 1999

- Heuman, Jackie, ed. 1999. Material Matters: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture. London: Tate Gallery Publishing.

- Hummelen, Sillé, and Zijlmans 1999

- Hummelen, IJsbrand, Dionne Sillé, and Marjan Zijlmans, eds. 1999. Modern Art: Who Cares? An Interdisciplinary Research Project and an International Symposium on the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art. Amsterdam: Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art.

- Learner and Rivenc 2014

- Learner, Tom, and Rachel Rivenc. 2014. Conserving Outdoor Painted Sculpture: Proceedings from the Interim Meeting of the Modern Materials and Contemporary Art Working Group of ICOM-CC. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Levin 2012

- Levin, Jeffrey, ed. 2012. “Conservation of Public Art.” Special issue, Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 27 (2): https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/pdf/v27n2.pdf.

- McNally and Hsu 2012

- McNally, Rika Smith, and Lillian Hsu. 2012. “Conservation of Contemporary Public Art.” Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 27 (2): 4–9.

- Michalski and Pedersoli 2016

- Michalski, Stefan, and José Luiz Pedersoli Jr. 2016. The ABC Method: A Risk Management Approach to the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. Ottawa: Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute, and ICCROM.

- Pullen and Heuman 2007

- Pullen, Derek, and Jackie Heuman. 2007. “Modern and Contemporary Outdoor Sculpture Conservation: Challenges and Advances.” Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 22 (2): https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/22_2/feature.html.

- Rolnik 2002

- Rolnik, Suely. 2002. “Flowerings of Reality.” In Anna Maria Maiolino: Vida afora = A Lifeline, edited by Catherine de Zegher and Paço Imperial, 110–11. São Paulo: Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo; New York: Drawing Center.

- Scholte and Wharton 2011

- Scholte, Tatja, and Glenn Wharton, eds. 2011. Inside Installations: Theory and Practice in the Care of Complex Artworks. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Verbeeck 2016

- Verbeeck, Muriel. 2016. “There Is Nothing More Practical Than a Good Theory: Conceptual Tools for Conservation Practice.” Studies in Conservation 61, supplement 2: 233–40.