8. Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration and Innovation in the Exhibition of Living Matter at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe: The Case of the Planetary Community Chicken Exhibition

- Davison Chiwara

The National Gallery of Zimbabwe was officially established in 1952 through an act of parliament, and opened to the public in 1957 as a center for exhibiting sculptures, paintings, drawings, print works, and installations by Zimbabwean and international artists. It acquires traditional and contemporary art from local and international artists through loans, bequests, purchases, and donations, and likewise exhibits both traditional and contemporary art. An appropriate environment must be provided for the conservation of all artworks on view, and thus the exhibition of living matter as contemporary art can be a challenge due to its fragile and complex nature.

The exhibition team for the 2016 show Planetary Community Chicken was made up of Koen Vanmechelen and his exhibition crew from Belgium; Chido Govera, a Zimbabwean entrepreneur specializing in mushroom and poultry farming; Raphael Chikukwa, the exhibition’s curator; and gallery staff from the Conservation and Collections, Exhibitions, Workshop, Education, and Public Programming departments. Vanmechelen and Govera came up with the concept and provided the key resources, including the chickens and mushrooms. The role of Conservation and Collections was to preserve the exhibited elements as well as other artworks in the gallery. Workshop provided equipment and crew for the installation. Vanmechelen’s crew and Exhibitions were responsible for designing the presentation and led the installation work. Education prepared learning materials, and Public Programming publicized the exhibition to the media, corporate and other sponsors, and the public.

Planetary Community Chicken was the first show of its kind in terms of exhibiting living matter at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe. Its goal was to leverage the museum as a respected public platform to empower people with the knowledge necessary to diversify their agricultural activities, specifically through the production of chickens, eggs, and mushrooms for self-sustenance (mushrooms are an excellent source of fiber and protein).

The idea was born of an urgency to educate citizens about the need to restock a local species of roadrunner, which had depleted due to diseases resulting from inbreeding. The chickens in the show were a new species resulting from the crossbreeding of Vanmechelen’s cosmopolitan rooster with the Zimbabwean common chicken, also known as the roadrunner. The resultant offspring are less susceptible to disease, stress, and physiological problems than the roadrunner.

The intended audiences for the demonstrated food production system involving chickens and mushrooms were rural communities in Zimbabwe surrounding the capital city, Harare; the exhibition was connected to a social project of empowering residents. The new breed of chicken was donated to them to be used for crossbreeding with local chickens beyond the exhibition. One such community was Seke, where local residents successfully crossbred the chickens, produced eggs, and grew mushrooms. The production fulfilled their consumption needs, and the surplus was sold.

The exhibition was an intricate one, demanding a conscious conservation mindset to keep the chickens alive as well as ensuring that the chicken eggs and mushrooms remained fresh for the month-long duration of the show. Caution was also taken to prevent potential pest infestation of other artworks, especially those composed of organic materials, for instance sculptures, paintings, drawings, or prints made using wood or paper.

Conservation Challenges

Contemporary artworks containing biological materials such as food, bodily fluids and/or tissues, plants, animals, and animal parts pose specific challenges for museums, conservators, and collectors. They are prone to illness, decay, putrefaction, and eventual disappearance, which makes them difficult to exhibit and preserve for future museum visitors. In the case of this exhibition, numerous challenges presented themselves. Confinement of live chickens in an environment that is too hot or cold, without sufficient ventilation, without regular cleaning or hygiene, or without adequate feed or water can cause illness, stress, even death. A hot environment also causes the decomposition of chicken eggs. Mushrooms will likewise not survive if they are exhibited in an unregulated environment; overly hot temperatures, lack of humidity, or inadequate watering can all result in wilting and decomposition. In light of all this, the exhibition of live chickens, chicken eggs, and mushrooms required an understanding of issues that are vital for their preservation.

Innovation for the Conservation of Living Matter and Artworks

Pest Control

The exhibition team proactively addressed potential pest hazards. The nests prepared for the egg-laying chickens were to be made from logs gathered in the forest—these nests would be more cost effective for the gallery compared to buying specially prepared nests from the market—but they posed a greater possibility of pest infestation on both the chickens and other artworks made from organic materials. Thus, the nesting materials were treated with pesticides, then covered with black polyethylene sheets and placed for a prolonged time in the sun to kill any pests present (fig. 8.1, fig. 8.2a, fig. 8.2b). This was a low-cost method of preventing pest infestation in the gallery, since the museum had no fumigation chambers.

Additionally, the museum environment was disinfected to prevent the outbreak of diseases that affect chickens.

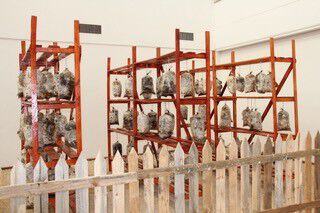

Mushrooms are a fungus whose spores could potentially harm some of the gallery’s organic artworks. To prevent this, polyethylene bags were used for mushroom production, which helped to contain the mushroom spores and prevent them from entering the galleries (fig. 8.3a, fig. 8.3b).

Creating an Environmentally Friendly Atmosphere for Living Matter

The exhibition team created an all-encompassing installation, transforming the Courtauld Gallery wing into a representation of a farmyard (fig. 8.4a, fig. 8.4b) with enough space to allow free air circulation, which in turn created a cool environment, preventing stress and suffocation of chickens or rotting of the chicken eggs and mushrooms. The exhibition team added soil to the main ground-floor space along with a wooden palisade fence—an enclosure mirroring a typical fowl run. The fowl run allowed for free movement of the chickens and ample space for them to forage living organisms in the soil.

Figure 8.4a

Figure 8.4a Figure 8.4b

Figure 8.4bGovera was responsible for cultivation of the mushrooms. She noted: “We manipulate places around us into the right kind of incubators of the ideas or the activities we want to carry out. . . . Chickens were scratching on the floor, they were mating, they were laying eggs, eggs were incubated.” The transformation of the gallery’s wing was in line with Amalia Kallergi’s assertion that for an institution to host a living exhibition, it must undergo spatial modifications and introduce new routines and procedures into its normal practices ().

The gallery’s transformation complied with the provisions of ICOM, which stress that, with regard to living collections, special consideration should be given to the natural and social environment from which they derive. Institutions should display live animals only if they can be looked after appropriately, and when they can form part of a positive message about nature for visitors (, 10, 15; , 3). The exhibition team did this by simulating a natural environment in which chickens and mushrooms can be cultivated successfully.

Installation of Chicken Hutches

The chicken shelters were two Zimbabwean-style hutches and two Senegalese-style hutches. According to Chikukwa, the curator, the juxtaposition was intended to show cross-cultural similarities in the rearing of chickens in these two countries. The similarities involve the use of dagga (an earthen structure made by molding clay mixed with water) and thatch. These materials help regulate temperatures, keeping chickens warm when temperatures are low, and cool when temperatures are high. The only difference is that the Senegalese hutches are elevated, whereas the Zimbabwean hutches are not (fig. 8.5a, fig. 8.5b).

Feeding of Chickens

The chickens foraged for food and other organisms found in the soil, but the exhibition team also provided supplementary feed and fresh drinking water to keep them healthy and thriving. Those responsible for this task acquired basic knowledge of domestic poultry rearing from an ordinary level agriculture subject (a practical subject offered at secondary schools under the Zimbabwe School Examinations Council).

The Preservation of Mushrooms

According to Govera, mushroom production is an indoor activity requiring an environment with sufficient humidity and air flow. She stated that the creation of this environment in the gallery was an interpretation of science in the form of art. The exhibition team provided shelves for the mushrooms and sand on the ground to maintain the required humidity. The mushrooms were kept fresh by watering them in the morning and evening throughout the duration of the exhibition. Mature mushrooms were harvested, and pieces of mushroom that fell to the ground were removed to keep the environment clean.

Govera further explained that they housed the mushrooms in polyethylene bags to keep them fresh (see fig. 8.3a, fig. 8.3b) and highlighted a long process that started with the humidification, pasteurization, and incubation of the bags before the gallery installation. Nutrients for mushroom growth were added to the bags as part of the incubation process.

Importance of Collaboration in the Exhibition of Living Matter

Cross-disciplinary collaboration was crucial in preserving living matter in the Planetary Community Chicken exhibition. In addition to the creative collaboration between artist Koen Vanmechelen and entrepreneurial mushroom and poultry farmer Chido Govera that led to the concept for the exhibition, staff members from the gallery’s various departments were essential in executing and maintaining it. The involvement of people from different disciplines created a hub of ideas and skills as well as human and material resources for the successful exhibition of living matter. Everyone shared an understanding of the need to provide an environment suitable for preserving a living ecosystem. Govera, who has collaborated with Vanmechelen since 2012—their projects have been featured at the 2014 Havana Biennial and the 2015 Venice Biennale—states: “The key to a successful exhibition of chicken and mushrooms in the gallery was understanding and appreciation of each other’s work. I have an appreciation of [Vanmechelen’s] work, and he has an appreciation of my work. It’s just merging these two roles, which are complemented by Koen’s artistic eye in the context of art. He is an exceptional artist who can transform anything into art.”

Their long history of working together on international exhibitions made it possible for them to bridge their disciplines and collaborate in exhibiting living matter in Planetary Community Chicken. Their artistic collaboration was supported by the commitment of the gallery staff, who provided the needed person-hours, resources, and guidance on technical aspects. The exhibition of biological art poses complex issues, often requiring collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches to conservation. Beyond the artist’s creative vision, other experts must provide technical knowledge and skills (; ).

The involvement of experts from different disciplines enabled the museum to provide an environment and facilities that supported the preservation of living matter. This cross-disciplinary collaboration created an “innovation hub” for the preservation of live chickens, fresh eggs, and fresh mushrooms in the gallery. Innovative ideas emerged from this hub, transforming the Courtauld Gallery into an environment mirroring a real fowl run supporting live chickens and eggs and the growing of mushrooms.

Preventing any cruelty to the chickens was an important consideration in the overall design of the exhibition environment. The team’s collaborative efforts provided key facilities and an environment that guaranteed the safety of the chickens. Cruelty to animals manifests in various forms such as physical harm, psychological pain, exploitation, health risk, and commodification of animals (). All these were prevented by the exhibition team; the chickens felt at home and looked healthy, with no signs of psychological or physical harm. With regard to the ethics of exhibiting living animals, institutions, artists, and art historians are entangled in tricky discussions about the rights and treatment of animals (). Such challenges were not encountered in Planetary Chicken Community, as the exhibition team observed the rights of the chickens through an environment that supported their survival.

Conclusion

The Planetary Chicken Community exhibition attracted many visitors from all walks of life. The exhibition showcased a project run by Chido Govera in rural areas to empower communities to be more self-sufficient in food production. The project on the crossbreeding of the chickens and the growing of mushrooms empowered communities with knowledge for rearing chickens and growing mushrooms for healthy nutrition and a source of livelihoods.

The exhibition fused science and art. It was a novel and challenging undertaking for the gallery, as it encompassed living matter that required the transformation of the gallery environment in order to preserve it, as well as the adoption of precautionary measures to protect the organic artworks in the collection from potential pest infestation.

Planetary Community Chicken showed that the integration of different disciplines, a shared goal, proactive teamwork, and mutual understanding among the exhibition team members are vital in the conservation of living matter in a museum. The conservation discipline immensely benefits from tapping into the knowledge of other fields to safeguard living matter and other artworks in a museum. A common goal ensures shared responsibilities and overlapping of tasks among members of the exhibition team, which simplifies work on exhibiting living matter. Proactive teamwork helps in identifying critical conservation needs in the exhibition of living matter and ensures that the needs are addressed in a timely manner. Mutual understanding between the artist and exhibition team members helps in the fusion of ideas in transforming living matter into art in a museum. The preservation of living matter in museums is a complex issue requiring versatility and integration of people from different disciplines, including artists, conservators, curators, exhibition designers, and other stakeholders. These were key in Planetary Community Chicken, where collaborative efforts ensured a smooth flow of operations.

Bibliography

- DiNoia 2019

- DiNoia, Megan. 2019. “Decomposing Art: How Museum Professionals Treat Living Matter.” Heritagebites, April 15, 2019, https://heritagebites.org/2019/04/15/decomposing-art-how-museum-professionals-treat-living-matter/.

- ICOM 2006

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). 2006. ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums. Paris: ICOM.

- ICOM 2013

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). 2013. ICOM Code of Ethics for Natural History Museums. Paris: ICOM.

- Kallergi 2008

- Kallergi, Amalia. 2008. “Bioart on Display: Challenges and Opportunities of Exhibiting Bioart.” Leiden, the Netherlands: Leiden University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266333742_Bioart_on_Display-_challenges_and_opportunities_of_exhibiting_bioart.

- Kaplan 2017

- Kaplan, Isaac. 2017. “When Is It Okay to Use Animals in Art?” Artsy, May 11, 2017, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-animals-art.