21. A Crumb(ling) Display: Conserving Bread in the Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb

- Mirta Pavić

- Jasna Jablan

- Ivana Bačić

- Harald Fitzek

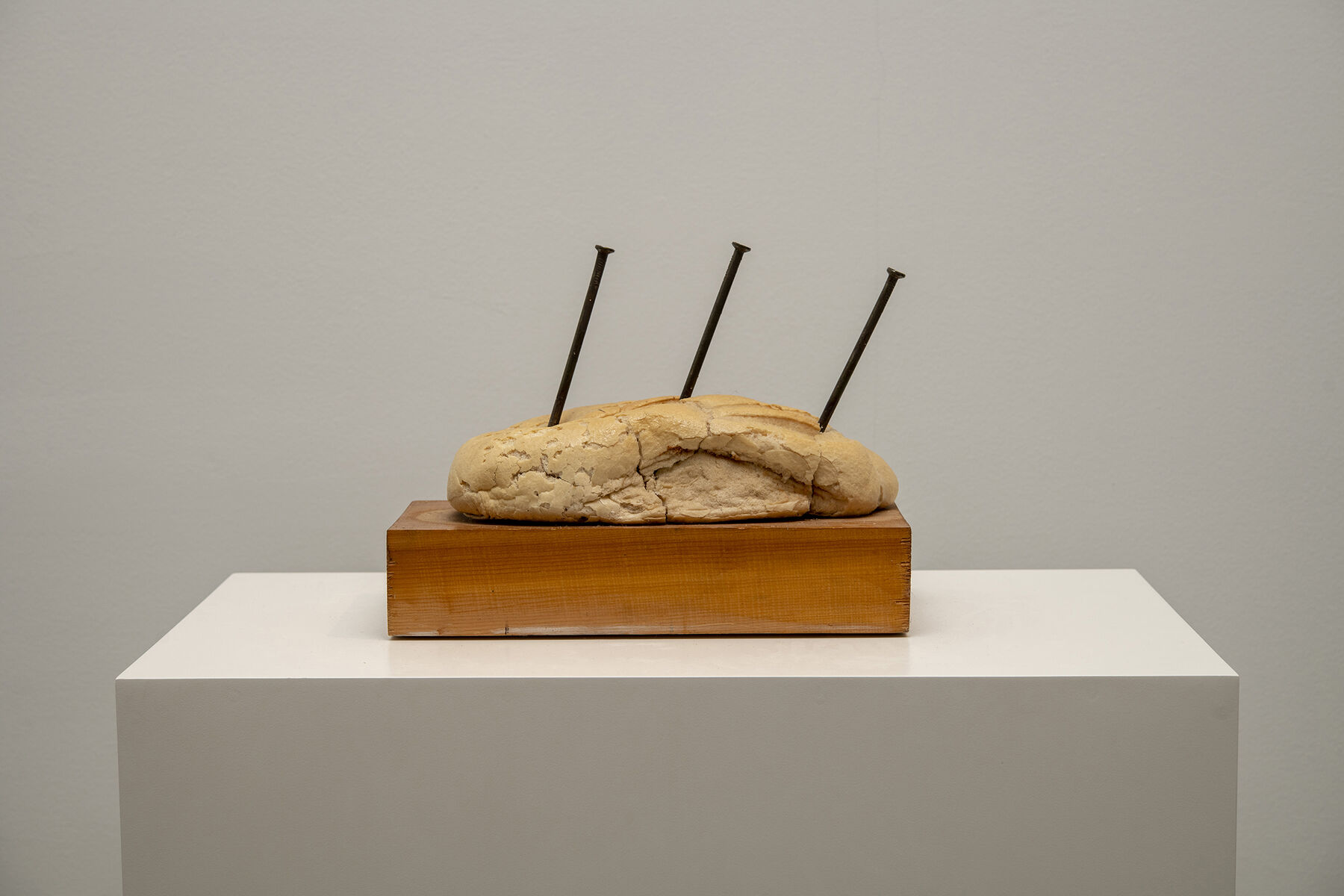

One’s first association with bread is likely food. But this simple ingredient found a place for itself in an entirely different context in the work of Dragoljub Raša Todosijević (b. 1945), a pioneer in the field of conceptual art in the former Yugoslavia. Nailed Bread (1973, fig. 21.1) belongs to Zagreb’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MSU), and is among the most exciting artworks on permanent view, judging by public feedback. It is no less interesting from a conservation point of view. In order for this perishable material, through which the artist rejects the idea that an artwork is merely an object, to retain its original form and consistency, it must be preserved with particular care.

Figure 21.1

Figure 21.1Nailed Bread is an unmistakable example of an artwork made of a material that is at the same time its primary bearer of meaning. Bread is the material from which it is made, but it simultaneously brings to mind staple foods, and the Crucifixion, in this way breaking down the barrier between art and life.

In 2009 the MSU moved to a new purpose-built building, where Nailed Bread was exhibited as part of the permanent collection from the very beginning. The permanent collection is not static, but periodically rotated within the gallery space. In 2010 Nailed Bread was exhibited in close proximity to other organic materials, such as Philip Corner’s installation Piano Bed (1999, fig. 21.2), which is made of an upright piano, hay, and a cap. This probably contributed to the changes that were noted on the bread in the same year, almost four decades after its creation.

Figure 21.2

Figure 21.2Earlier Treatments

Raša Todosijević’s work is, for the most part, focused on communicating with viewers through the production of a deceptively realistic piece () and performances and texts in which he discusses his own works, rather than through static objects.1 The MSU work speaks through its symbolism and belongs to the museum’s collection of sculpture. In 2010, when the first changes—drying, cracking, and crumbling—were noted, it was therefore logical to telephone the artist (who is still living, and resides in Belgrade) to determine his attitude toward the preservation of this piece from 1973. Given that the artist used bread in many of his works, he immediately suggested that he donate a new piece of bread to the museum to replace the existing one; he had been unaware that there was even a possibility of conserving the original bread. But for us, the fact that ours is not the only bread piece by Raša Todosijević was an additional motive to attempt conservation of the original bread. The artist was informed that our intention was to consolidate the bread and expose it to gamma irradiation to eliminate insect infestation. He was very surprised, happy, and eager to hear about the results.

A solution of ethyl-methacrylate copolymer Paraloid B-72 in ethanol (6 percent) was tested on a dried piece of bread baked from the same type of flour as the original. The consolidated sample was stable, and showed the desired characteristics during a test where it was dropped to the floor, in comparison to a sample that was not consolidated, which broke apart into little pieces (fig. 21.3). The original bread was then taken apart into the elements that it had already broken into through the natural process of drying out (fig. 21.4). Small decayed parts were removed from the interior, and the nails were cleaned and coated with an anti-corrosive liquid. Paraloid B-72 was then injected into the material (fig. 21.5). The separated parts of Nailed Bread were then successfully joined using the same consolidant. Thereafter, the object was exposed to gamma irradiation at the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb.2

Changes in the bread once again appeared in late 2018, namely minor local disintegration and tiny flying insects around it, which led to the suspicion that the consolidant had not been homogenously spread out across the material. It was therefore decided that the piece would be reexamined, and various consolidants tested in order to compare their characteristics to Paraloid B-72. The primary characteristics sought in the consolidant were: zero or minimal impact on visual appearance and aesthetics; the possibility of dissolving in a solvent that evaporates quickly (as the authors were concerned that prolonged contact with the bread could harm it) and that it not break down the starch; stability; and resistance to parasites.

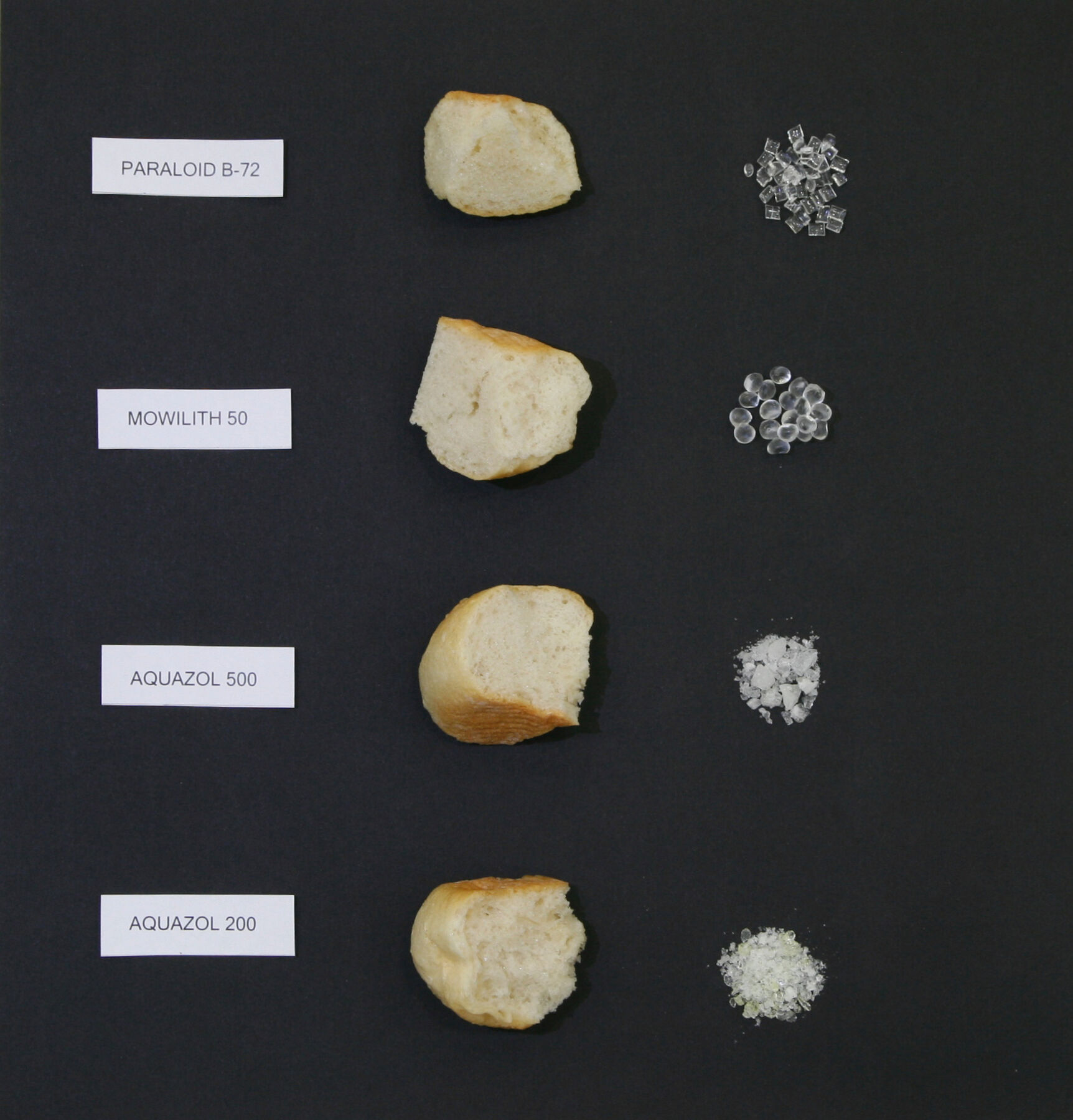

Four consolidants were tested on the bread samples, all synthetic resins that could dissolve in a fast-evaporating solvent: polyvinyl acetatehomopolymer (Mowilith 50),3 poly (2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) (Aquazol 200 and 500),4 and Paraloid B-72.5 Every sample of bread tested with a consolidant was compared to a sample of the original consolidated bread.

Materials and Methods

Samples of bread having the same qualities as the original bread (a white bread commonly used in this region and available in all grocery stores) were prepared and consolidated with the four different polymer resins (fig. 21.6). Solutions were made using different concentrations of the consolidants (6, 10, and 15 percent solutions in ethanol). The consolidants were injected into each sample using a syringe with a needle.

Optical microscopy, Raman microscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy–attenuated total reflection (FTIR-ATR), and correlative scanning electron microscopy (SEM)–Raman microscopy () provided the details necessary for the conservators to make decisions.6 The aim was to gather information on the behavior of the consolidant applied in the first treatment (Paraloid B-72) over the period of nine years in comparison with the four new consolidants applied to the test samples. Surface characterization, changes due to conservation treatment, and evaluation of spatial distribution of the constituents were determined with FTIR-ATR. There are many advantages to this technique: it is nondestructive, does not require any sample preparation, and gives molecular information on inorganic and organic components. FTIR-ATR spectroscopy provides information about functional groups present in molecules based on the energy of vibrational transitions.

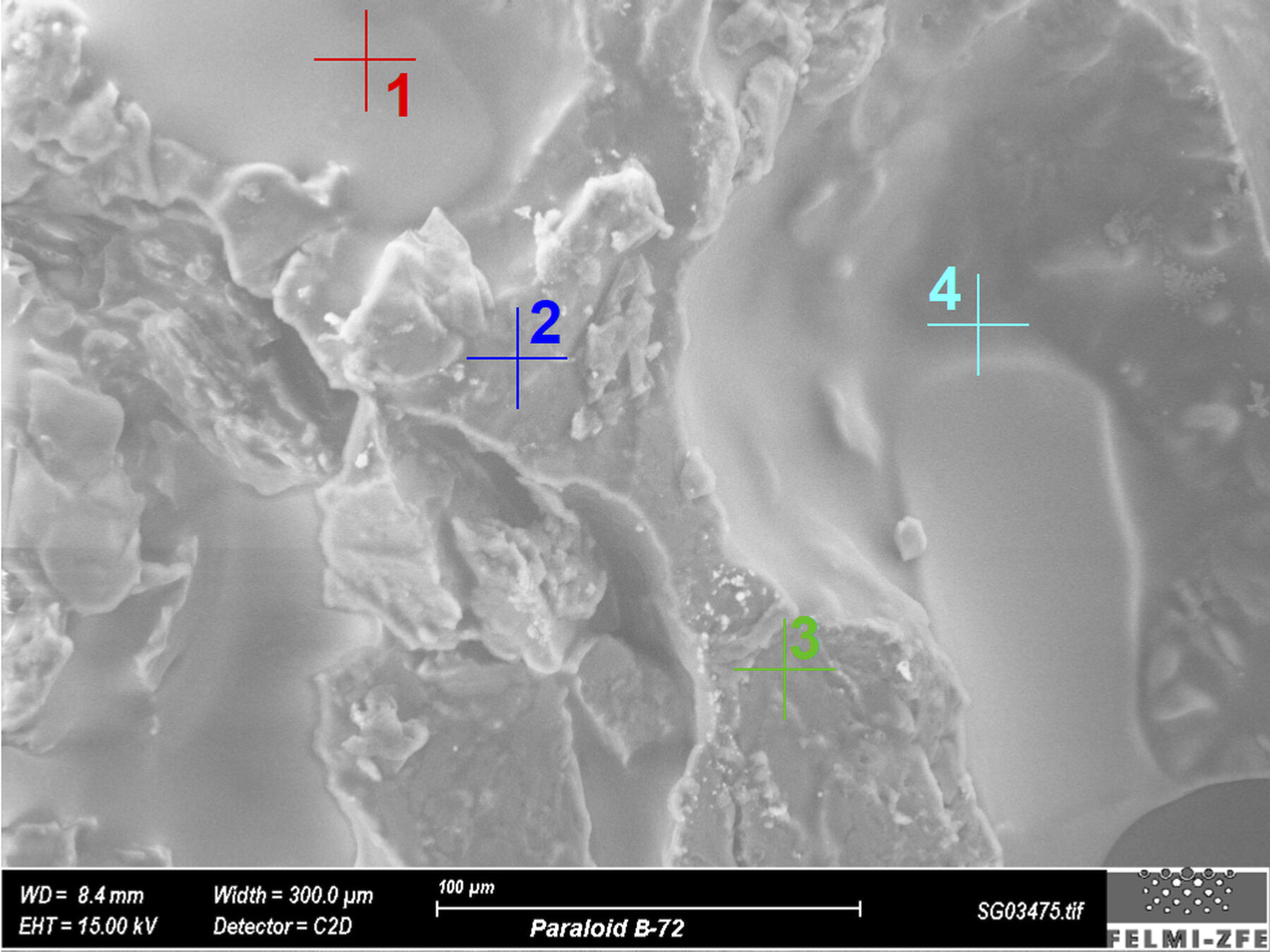

A complete picture of the chemical distribution of the components within a test sample may be obtained using Raman microscopy, which can provide chemical analysis on a micrometer scale. In addition, correlative SEM-Raman microscopy was performed as a novel technique that combines the high spatial resolution and depth of focus of SEM with the chemical analysis of confocal Raman microscopy.

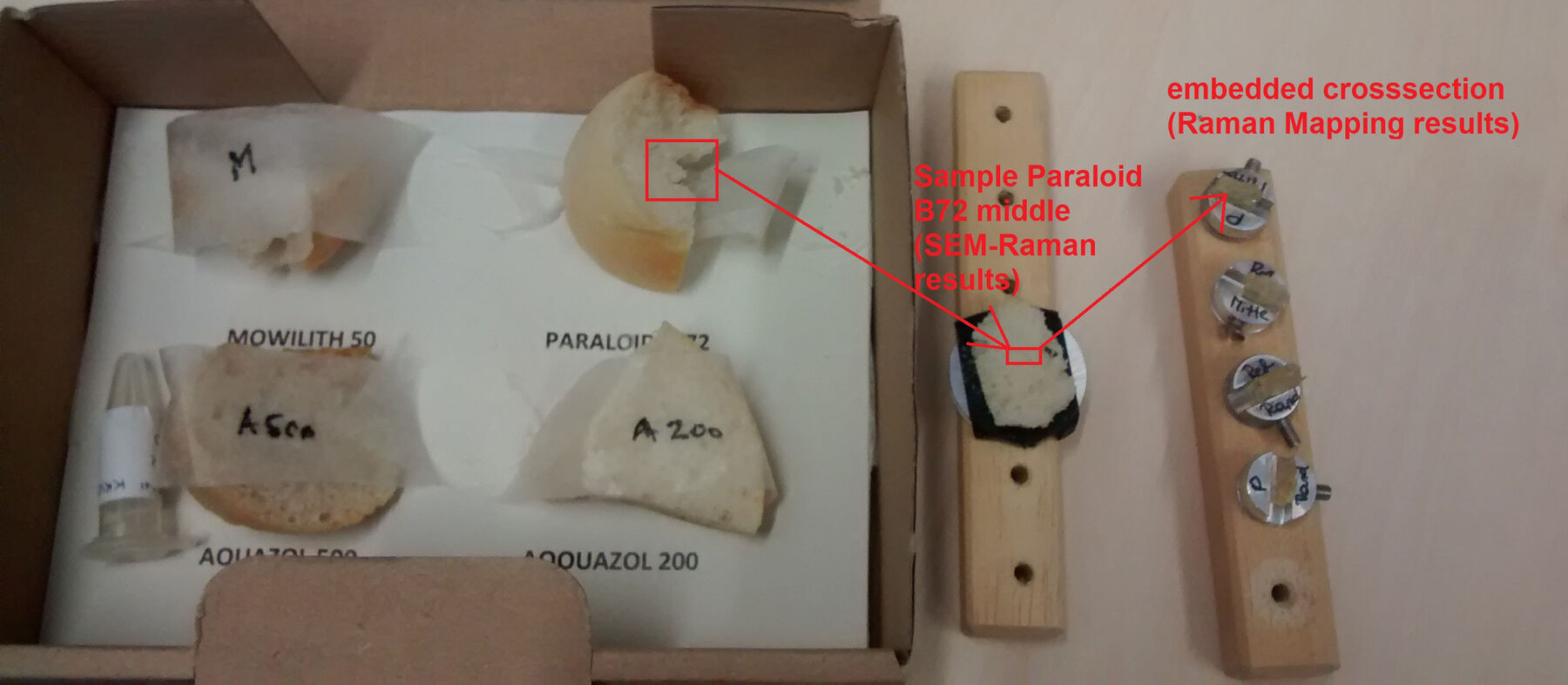

Consolidated bread samples with various resins and concentrations were prepared and cured. These included samples of the original bread consolidated nine years ago as well as the newly prepared and consolidated samples. Samples used for SEM-Raman microscopy were prepared by simple cut. Parts of these samples were embedded in epoxy resin using flat embedding molds, dried at room temperature, and cut with ultramicrotomy (Leica UC6; Histo diamond knife) in order to produce a flat block surface for microscopic measurements and for Raman mapping (fig. 21.7).

Results

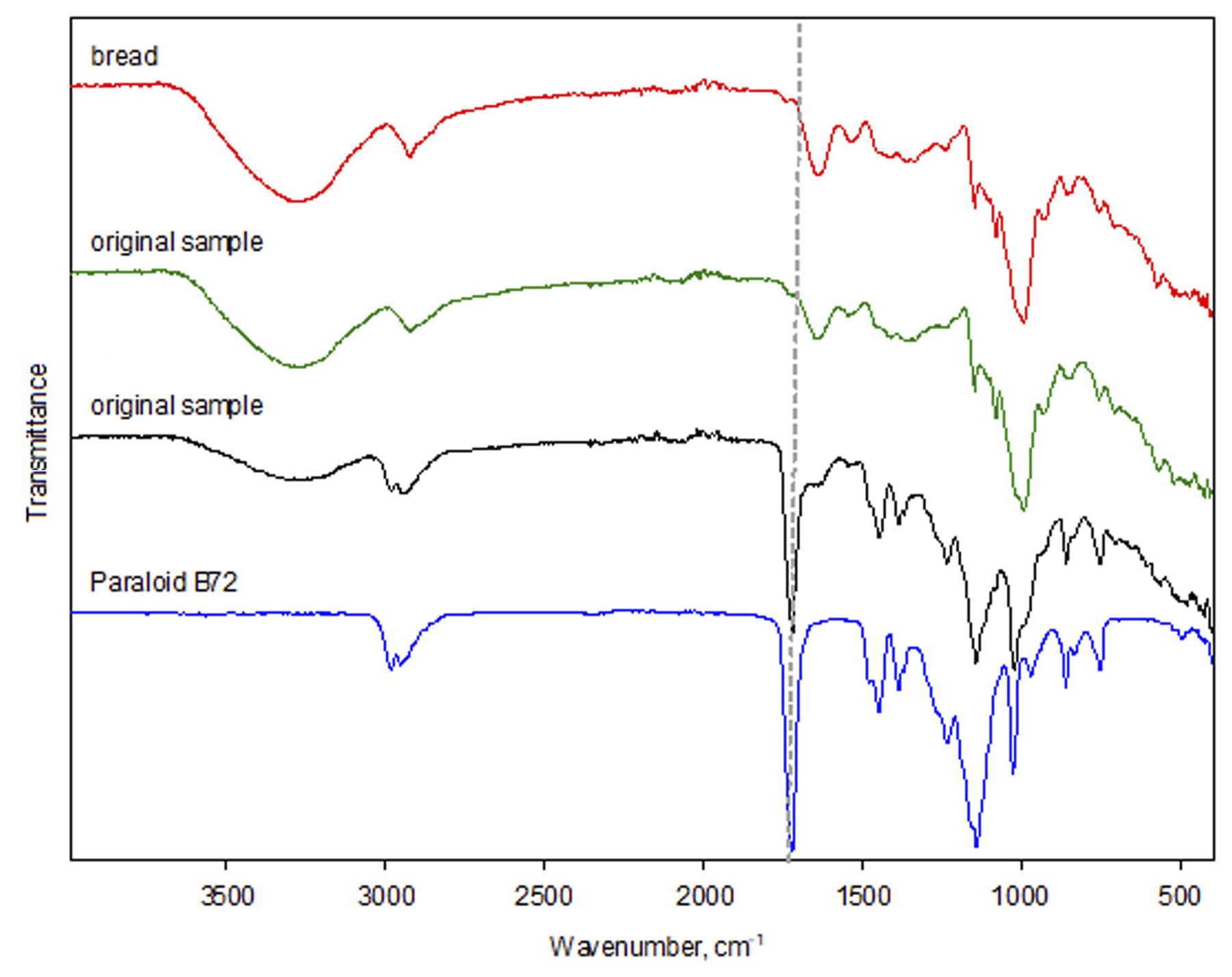

FTIR-ATR was used to determine how homogeneously the consolidant had penetrated the bread samples. The obtained spectra for untreated bread (without any consolidant), samples taken from the original object consolidated with Paraloid B-72, and pure solution of Paraloid B-72 in ethanol are shown in fig. 21.8. The line drawn at 1723 cm-1 signals the absorption band related to carbonyl stretching (ν C=O) characteristic for Paraloid B-72. This band was used as a marker for determining the presence of Paraloid B-72 in the sample, since it is not present in untreated bread. In addition, the variations in intensity as a function of location provided semi-quantitative information on the concentration of Paraloid B-72. The significant variations in intensity indicate an uneven distribution of Paraloid B-72 ().

Figure 21.8

Figure 21.8Unlike the Paraloid B-72 and Mowilith 50, as a marker for the Aquazol 200 and Aquazol 500, an absorption band with a maximum at 1195 cm-1 was used, since this band is not present in untreated bread. According to literature, this band is most likely attributable to the stretching of C–C bonds ().

Similar results were obtained for all the other samples analyzed. FTIR measurements were taken randomly at five different locations inside of each bread sample. At some points of measurement, very low concentrations of the consolidant were observed, while at some other points the concentration of the consolidant was very high. The characteristic absorption bands for each are listed in table 21.1, with the respective areas per location and per sample. The results indicate that the consolidant is unevenly distributed in all samples irrespectively of the concentration. The results also show that the consolidation of the new test bread samples as well as the original bread sample taken from the object that was consolidated with Paraloid B-72 in 2010 did not cause any change to the vibrational modes of the starch and selected polymer materials, suggesting that the consolidant is chemically stable, and compatible with the bread.

| Paraloid B72 | Mowilith 50 | Aquazol 200 | Aquazol 500 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| characteristic absorption band | 1723 cm-1 | 1723 cm-1 | 1195 cm-1 | 1195 cm-1 |

| Area of characteristic absorption band (average of 2 measurements) | ||||

| Pure consolidant | 18.96 | 18.73 | 2.15 | 12.95 |

| Area of characteristic absorption band analyzed at 5 different positions | ||||

| Bread with consolidant in 6% ethanol | 2.07 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.08 |

| 4.06 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.07 | |

| 0.56 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.09 | |

| 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | |

| 1.38 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.15 | |

| Bread with consolidant in 10% ethanol | 4.47 | 7.70 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| 1.23 | 1.07 | 0.13 | 0.16 | |

| 3.79 | 4.05 | 0.10 | 0.19 | |

| 0.92 | 7.63 | 1.03 | 0.26 | |

| 0.72 | 1.67 | 0.12 | 0.10 | |

| Bread with consolidant in 15% ethanol | 2.21 | 9.20 | 0.69 | 0.45 |

| 1.08 | 1.52 | 0.05 | 0.18 | |

| 2.50 | 17.74 | 0.90 | 1.28 | |

| 1.88 | 12.70 | 0.27 | 0.04 | |

| 1.59 | 4.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | |

| Paraloid B72 | Mowilith 50 | Aquazol 200 | Aquazol 500 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| characteristic absorption band | 1723 cm-1 | 1723 cm-1 | 1195 cm-1 | 1195 cm-1 |

| Area of characteristic absorption band (average of 2 measurements) | ||||

| Pure consolidant | 18.96 | 18.73 | 2.15 | 12.95 |

| Area of characteristic absorption band analyzed at 5 different positions | ||||

| Bread with consolidant in 6% ethanol | 2.07 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.08 |

| 4.06 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.07 | |

| 0.56 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.09 | |

| 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | |

| 1.38 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.15 | |

| Bread with consolidant in 10% ethanol | 4.47 | 7.70 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| 1.23 | 1.07 | 0.13 | 0.16 | |

| 3.79 | 4.05 | 0.10 | 0.19 | |

| 0.92 | 7.63 | 1.03 | 0.26 | |

| 0.72 | 1.67 | 0.12 | 0.10 | |

| Bread with consolidant in 15% ethanol | 2.21 | 9.20 | 0.69 | 0.45 |

| 1.08 | 1.52 | 0.05 | 0.18 | |

| 2.50 | 17.74 | 0.90 | 1.28 | |

| 1.88 | 12.70 | 0.27 | 0.04 | |

| 1.59 | 4.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | |

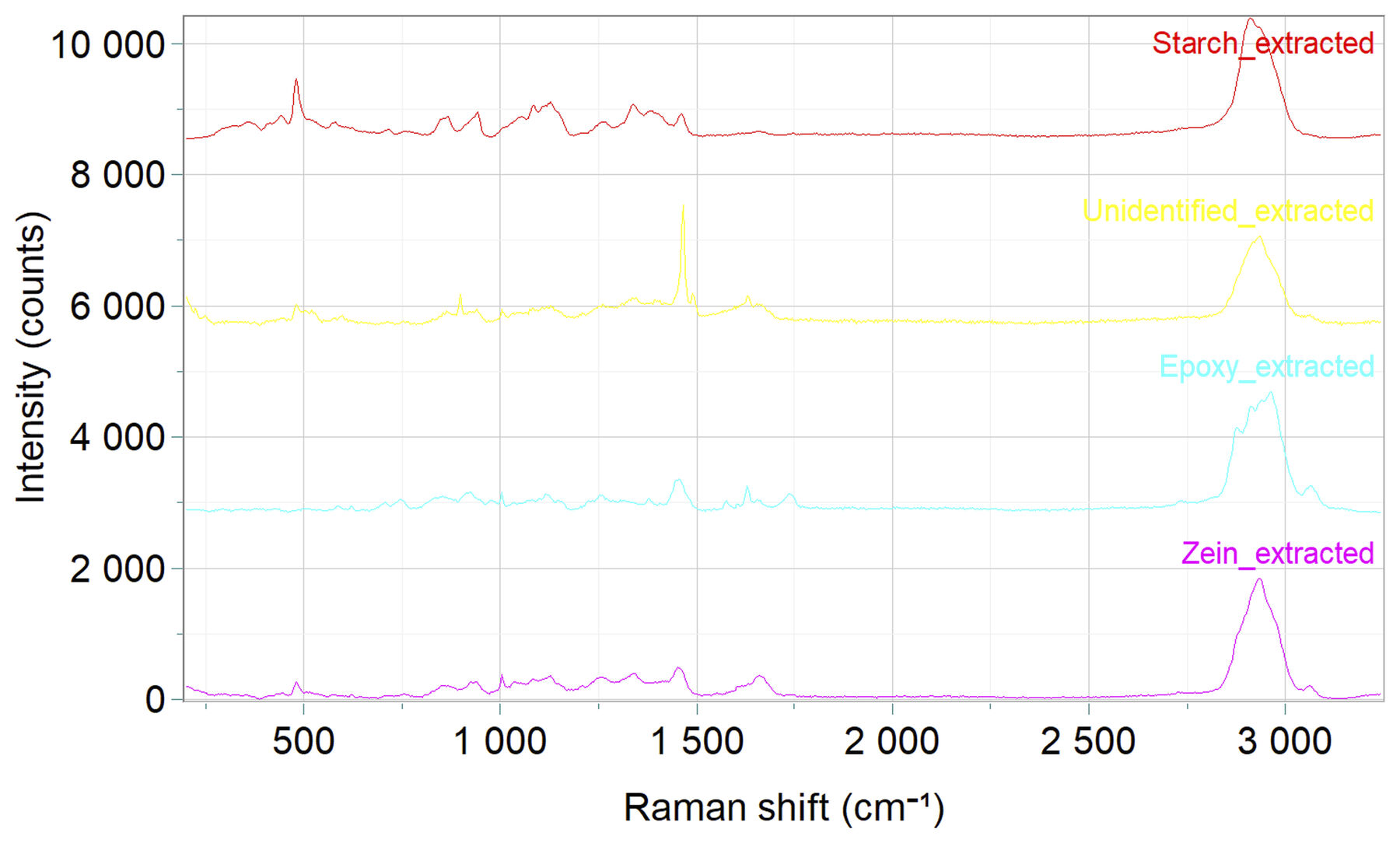

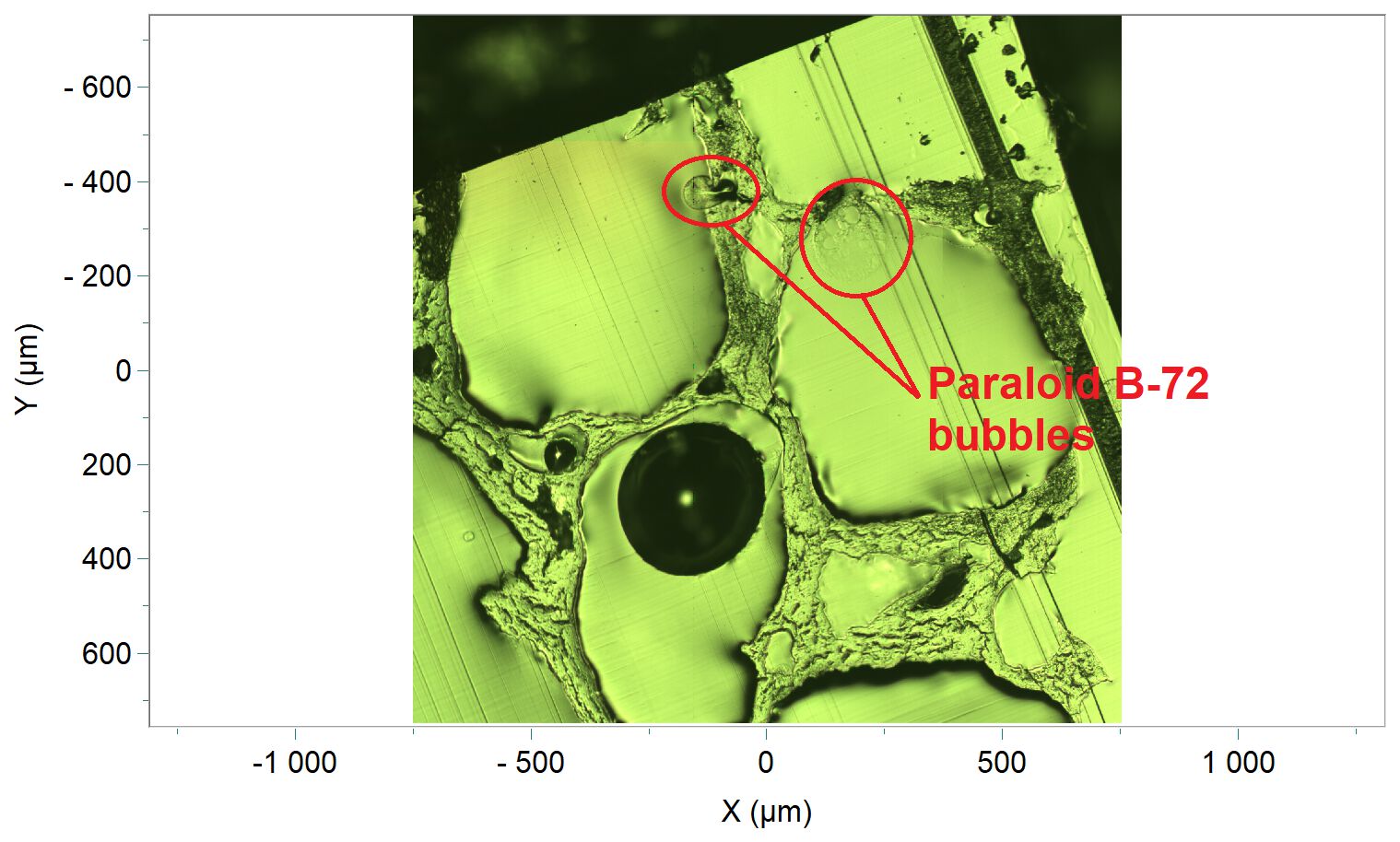

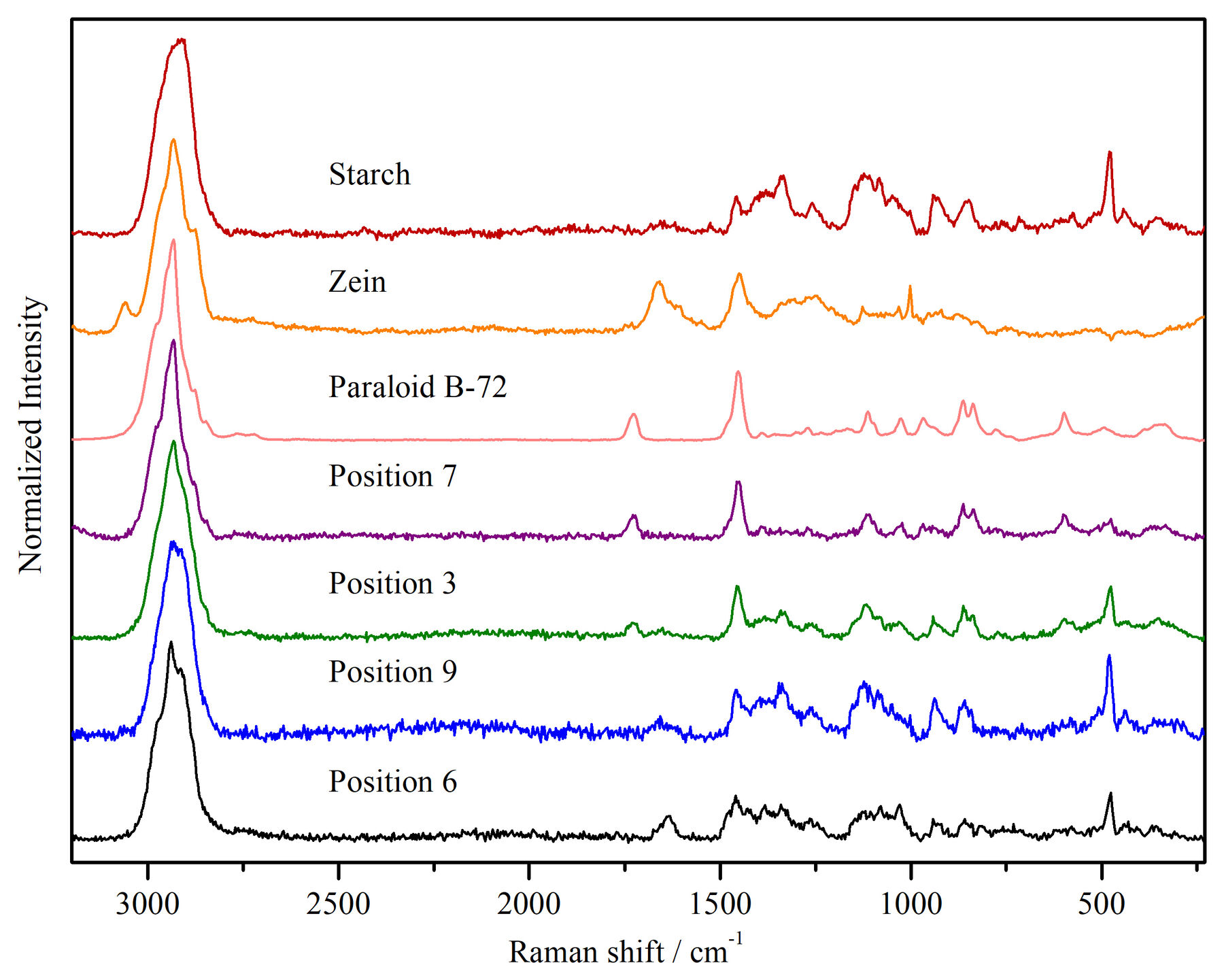

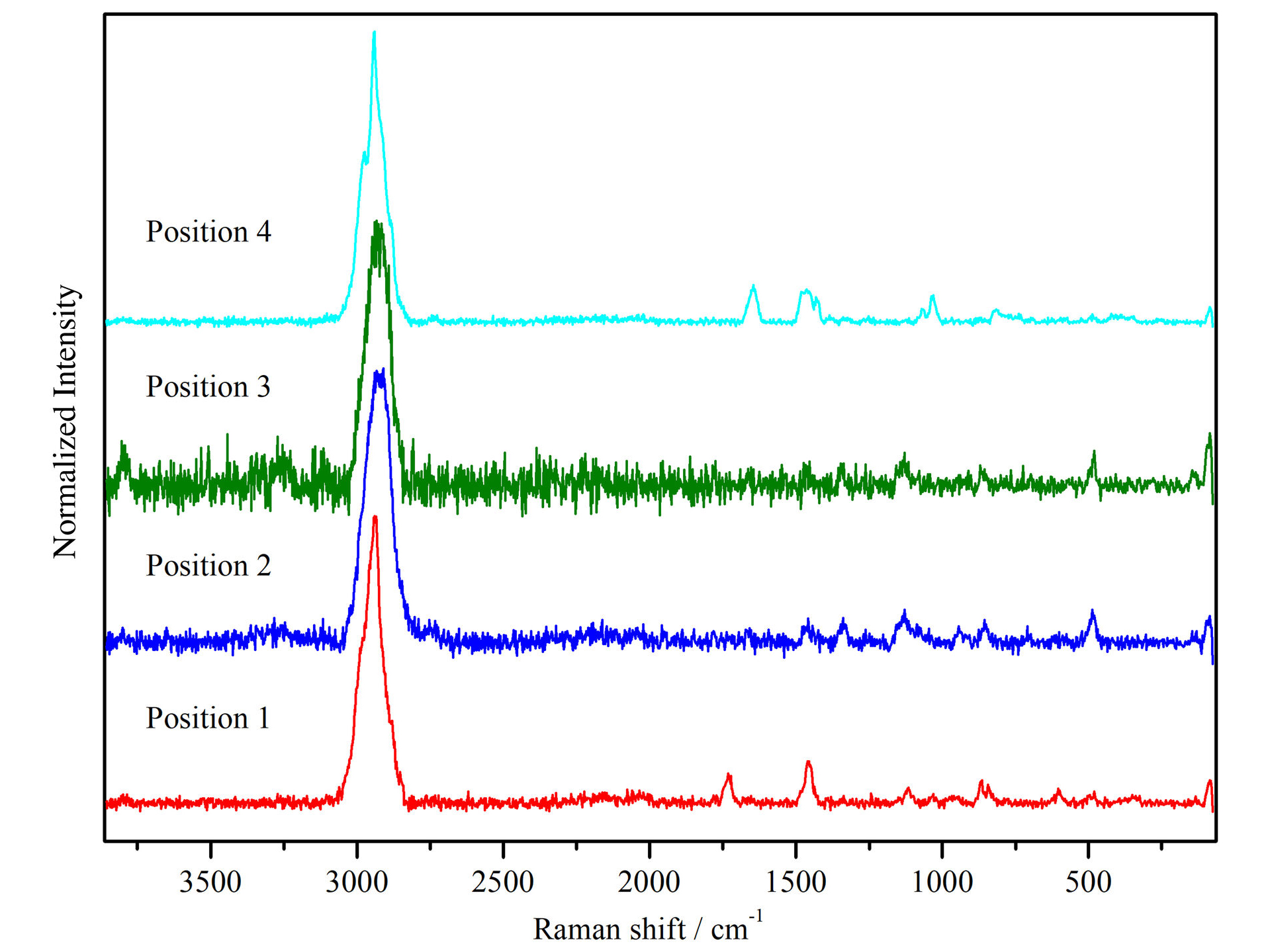

Optical microscopy and confocal Raman microscopy were used as further experimental analytical techniques.7 To confirm the results obtained by FTIR spectroscopy and for material characterization, optical microscopy on ultra-microtome cut samples was used. In the optical microscope image (fig. 21.9) it is fairly obvious that large droplets of Paraloid B-72 have formed. Raman measurements performed on ten different positions confirmed that the chemical composition of the bubbles observed using light microscopy corresponds to the composition of Paraloid B-72 (the spectra shown are 3 and 7, fig. 21.10). On the other hand, on all other positions analyzed, the presence of the consolidant used was not confirmed (the spectra shown are 6 and 9, fig. 21.10). Direct measurements on an unprepared piece of bread excluded any influence from our sample preparation. In all samples, the obtained results have confirmed the presence of starch and an additive (zein), and the presence of Paraloid B-72 was confirmed in the treated samples of bread.

Figure 21.9

Figure 21.9 Figure 21.10

Figure 21.10The results of light microscopy were also confirmed using a sophisticated Raman-SEM technique (). Two correlative Raman-SEM measurements of an unembedded part of the sample were performed. The SEM’s good depth of field was used to obtain reasonable images, and Raman point measurements were used to confirm the chemistry (fig. 21.11a, fig. 21.11b). The results obtained also showed the presence of droplets of Paraloid B-72 on the top of the bread.

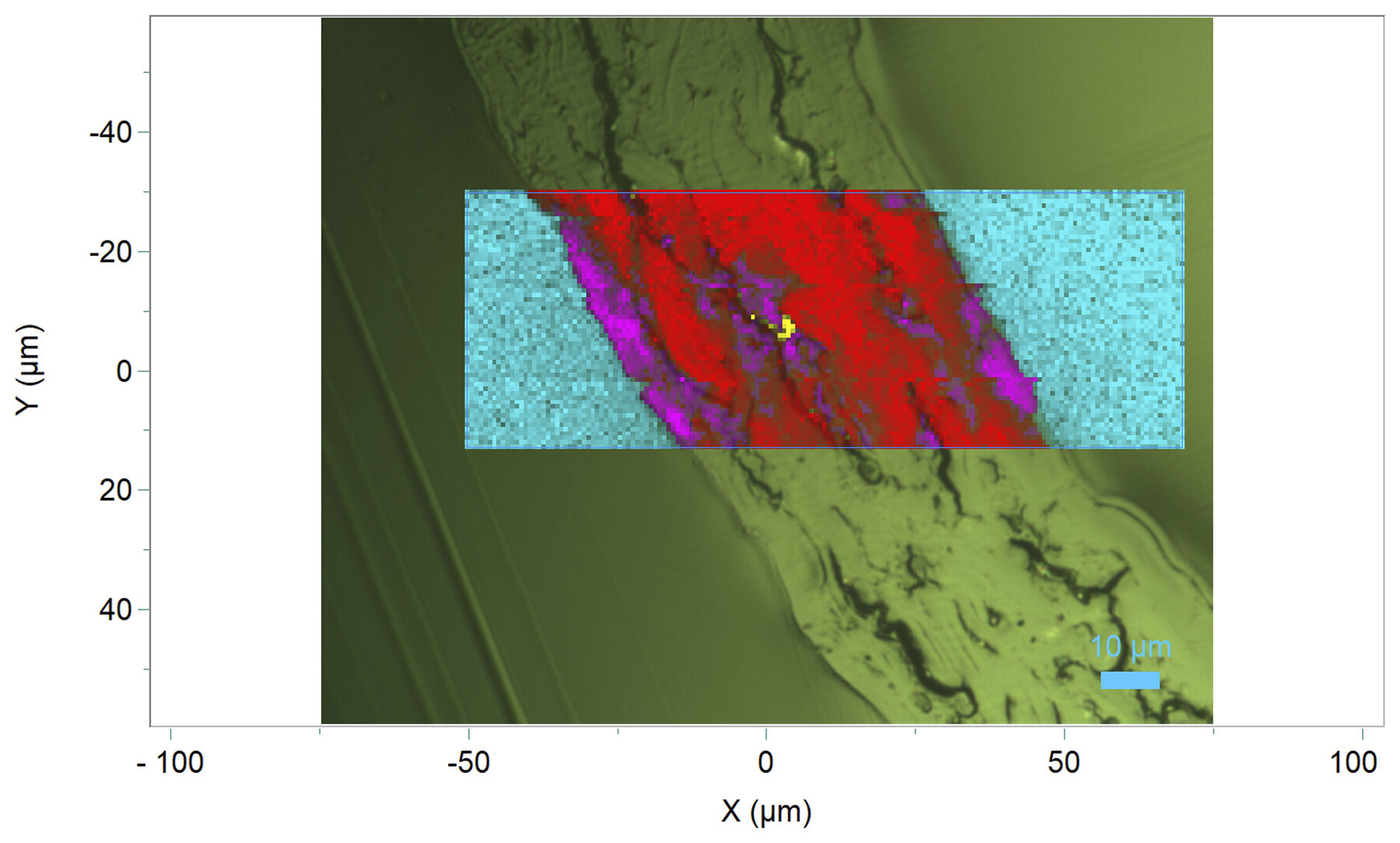

Based on observations obtained using light microscopy, Raman mapping was performed on one thread of the bread with no bubbles close by (fig. 21.12a, fig. 21.12b). In the mapping, only components belonging to the bread (starch and zein) and one unidentified contamination particle in the middle of the thread (but not Paraloid B-72) were found. The physical resolution of the mapping is approximately 1 µm and the pixel resolution is 0.75 µm, confirming that there is no thin coating of Paraloid B-72.

Figure 21.11a

Figure 21.11a Figure 21.11b

Figure 21.11bThe results of Raman point and mapping analysis confirmed the inhomogeneous distribution of Paraloid B-72 in the analyzed sample, present mostly in clusters of large droplets.

All other samples were analyzed in precisely the same way, and the same results were obtained for all the consolidants used (Mowilith 50, Aquazol 200, and Aquazol 500) (results not shown) through optical microscopy. Large droplets of consolidants had formed. Some droplets of the consolidant were found on the treated bread, but the threads of the bread were not completely covered by any consolidant, which was in each case confirmed using Raman point measurements. These measurements confirmed the results of the mapping of all analyzed samples, with some positions showing consolidants and others showing no consolidants (). The inhomogeneous distribution was observed in all analyzed samples.

Mycological Analysis

Because the presence of microorganisms was noted in Nailed Bread, a mycological analysis (examining test samples for the presence of fungi) was also performed. Dry swabs were taken from six spots on the object and inoculated on the surface of malt extract agar (MEA). Control swabs were taken from an indoor environment and inoculated on MEA. Samples were incubated at 25°C in the dark for ten days.

Afterward, the incubation plates were examined under an optical microscope. Object samples recovered white mycelia on two plates, Penicillium spp. and Chaetomium spp. on one plate and one unidentified colony, while two plates remained sterile. Control samples recovered Aspergillus from the section Nigri, Flavi, and Versicolores, Phomopsis spp., and Alternaria spp.

The only unusual finding on the object is Chaetomium spp., known as a tertiary colonizer of damp indoor materials. Since the object is kept in optimal environmental conditions, dry and with no visible mold growth, it is possible that some insects, perhaps flies, transferred the mold from another source to the surface of the object.

Concluding Thoughts

The research carried out thus far has led to a few significant findings. When it comes to biological material, it is important to act immediately, as soon as changes appear; if not, the material might be lost. To avoid the development of mold, it is important to isolate the piece inside a vitrine while it is on display and maintain optimal environmental conditions.

The aim of the research was to analyze the characteristics and behavior of the chosen consolidants. A lot of effort was put into this initial phase of research in order to better understand the biological material and improve its long-term preservation. The selection of consolidant is limited by the type of solvent used. Water, for example, should be avoided, as it breaks down bread. All the consolidants tested showed similar characteristics, but Paraloid and Mowilith might be a little shinier in appearance than Aquazol.

Results indicated that the consolidants tested did not cause a chemical change in the starch or its incorporation into the structure of the polymer backbone, which means that they are all potential consolidants for the conservation of this type of material. Confocal Raman microscopy indicated that all consolidants distribute unevenly and tend to accumulate as large droplets. Research into application methods that might improve the dispersion of the consolidant will continue, but overall, even with this imperfect application method, it was observed that the consolidants do prolong the life span of the bread.

Another observation on the method of application of the consolidants is that it is rather invasive: to spread the consolidant within the material, the needle needs to reach the depth of the material, in this case the bread. That said, this procedure did not affect the structure of bread due to its porosity and flexibility.

The different techniques have straightforward applications for the investigation of formation processes, mechanisms of degradation (chemical and physical), and interaction with the consolidant. Accelerated aging tests still need to be carried out on all of the samples with each of the consolidants in order to see how the consolidants react over a longer time period, as well as to test a greater variety of application methods.

Food as an artistic material transmits a message by being precisely what it is. The musealization of such materials opens up many ethical and technical questions (), as contemporary art often does, as well as collaborations with experts in different scientific fields. Artworks that contain organic materials especially require the establishment of methodologies for their maintenance. Nailed Bread belongs to the 1970s, a very productive time for conceptual art in the former Yugoslavia, on which Raša Todosijević left a mark. The object itself, made of the original material by the artist in this particular period, has an authenticity and a special meaning for the artist and for the museum. Replacing it with a new loaf of bread would require re-hammering the nails—an action that would not only change the work’s meaning, but alter its time and dating because it would take place in a new moment and under different circumstances.

The answers to some of the questions we encountered—Why this material in particular? Why is it important to preserve this particular piece of bread? What is so unique about it?—speak to the very fundamentals of our work, to thinking about and understanding what we do and why we do it.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Professor Maja Šegvić Klarić from the Department of Microbiology of the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry, for helping with the mycological analysis, and to the Austrian Center for Electron Microscopy and Nanoanalysis, Graz, and Sanja Šimić for their help in conducting the SEM-Raman experiments.

Notes

Raša Todosijević began his work in the informal Oktobar (October) group, together with Marina Abramović, Era Milivojević, Neša Paripović, Zoran Popović, and Gergelj Urkom, and they continued working in specific spheres of artistic activity, for instance the body-artistic activities of Abramović, and Raša Todosijević’s analysis of the social, as well as the political, function of art (, 3–4). ↩︎

This method is the easiest for eliminating insects that may be present, and when dealing with bread, irradiation of no more than 2 kGy is recommended; anything higher may lead to changes in the material, such as yellowing. ↩︎

This has a medium molecular weight and very good penetration and drying properties, and is effective on a wide range of substrates. Its excellent light stability means that it can be used in applications subjected to intense UV radiation. ↩︎

These have broad solubility in water and polar organic solvents, have good thermal stability, maintain a neutral pH, and have good solubility. They can be used as an adhesive, in painting medium, as consolidant, and as binder. Aquazol 500 molecular weight: 500,000; Aquazol 200 molecular weight: 200,000 ↩︎

This is a durable and non-yellowing acrylic resin more flexible than many other adhesives typically used. It tolerates more stress and strain on a join. ↩︎

Infrared spectra were recorded on a Bruker Alpha FTIR spectrometer with the single-reflection diamond ATR technique. Spectra were collected in frequency range of 4000 to 400 cm-1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1. In this study, samples were characterized using a novel correlative method combining SEM and Raman microscopy. The instrument used is a combination of a scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Sigma 300 VP) and a fast confocal Raman microscope (RISE, WiTec) operating independently in the same vacuum chamber and allowing correlated imaging between SEM and Raman for structural and chemical information in the same region of interest without complicated manipulation of the sample. ↩︎

Confocal Raman microscopy is a powerful characterization tool that allows collection of chemical information via Raman spectra with the same spatial resolution of a confocal laser microscope. The measurements were performed on a LabRAM HR 800 (with Olympus BX41) using a 532 nm laser (excitation power approximately 10mW) and an Olympus x50 LMPLFLN (NA=0.5) objective. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Colombo et al. 2015

- Colombo, Annalisa, Francesca Gherardi, Sara Goidanich, John Delaney, René de la Rie, Maria Ubaldi, Lucia Toniolo, and Roberto Simonutti. 2015. “Highly Transparent Poly (2-Ethyl-2-Oxazoline)-TiO2 Nanocomposite Coatings for the Conservation of Matte Painted Artworks.” RSC Adv. 5 (October): 84879–88.

- Hollricher, Schmidt, and Breuninger 2014

- Hollricher, Olaf, Ute Schmidt, and Sonja Breuninger. 2014. “RISE Microscopy: Correlative Raman and SEM Imaging.” Microscopy Today 22 (November): 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1551929514001175.

- Schmidt, Ayasse, and Hollricher 2016

- Schmidt, Ute, Philippe Ayasse, and Olaf Hollricher. 2016. “RISE Microscopy: Correlative Raman and SEM Imaging.” In European Microscopy Congress 2016: Proceedings, 1023–24. Wiley Online Library.

- Susovski 1978

- Susovski, Marijan, ed. 1978. Nova umjetničkapraksa 1966–1978. Zagreb: Galerija suvremene umjetnosti [Gallery of Contemporary Art].

- Tarnowski and Morris 2001

- Tarnowski, C. P., and M. D. Morris. 2001. “Raman Spectroscopy and Microscopy.” In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology, edited by K. H. Jürgen Buschow, Robert W. Cahn, Merton C. Flemings, Bernhard Ilschner, Edward J. Kramer, Subhash Mahajan, and Patrick Veyssière, 7976–83. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Temkin 1999

- Temkin, Ann. 1999. “Strange Fruit.” In Mortality Immortality? The Legacy of 20th-Century Art, edited by Miguel Angel Corzo, 45–50. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Tijardović 1978

- Tijardović, Jasna. 1978. “Marina Abramović, Slobodan Milivojević, Neša Paripović, Zoran Popović, Raša Todosijević, Gergelj Urkom.” In Nova umjetničkapraksa 1966–1978, edited by Marijan Susovski, 55–59. Zagreb: Galerija suvremene umjetnosti [Gallery of Contemporary Art].

- Vahur et al. 2016

- Vahur, Signe, Anu Teearu, Pilleriin Peets, Lauri Joosu, and Ivo Leito. 2016. “ATR-FT-IR Spectral Collection of Conservation Materials in the Extended Region of 4000-80 Cm−1.” Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 408 (13): 3373–79.