18. Pieces of the People We Love: Challenges in Caring for Works by Adrián Villar Rojas in the Moderna Museet Collection

- Thérèse Lilliegren

- Tora Hederus

- My Bundgaard

- Sara Norrehed

- Tom Sandström

No doubt there is a paradox within my practice: In order to keep on existing it has to be somehow preserved, and at the same time it involves disappearance and the political rejection of commodification as represented by the capitalocene-submissive form of art practiced in the twenty-first century.

—Adrián Villar Rojas, 2018

The conservation of artworks made from unconventional or unstable organic materials—materials that decay and change in galleries and storage spaces—poses challenges to traditional museum principles. This became evident in the encounter with works by Adrián Villar Rojas (b. 1980) at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm (fig. 18.1) in 2015. How should conservation meet and embrace the decay and entropy that are important to this work? A balance between artistic intent, curatorial needs, and conservation care was sought.

Figure 18.1

Figure 18.1A central notion in Villar Rojas’s work relates to time and life spans; ephemeral qualities are significant. Few of his former pieces still exist, and his previous productions are now mainly experienced through documentation. In this context, the decisions regarding any conservation action need to be carefully considered and executed. This paper describes the ethical and practical conservation concerns that were encountered in caring for the work of Villar Rojas. The initial challenges appeared when preparing the 2015 exhibition, but the later acquisition of two works in the show highlighted issues of long-term conservation. The project is a work in progress, and we are presenting our thoughts and actions so far.

Fantasma

In 2015 the Moderna Museet in Stockholm produced one of the first major museum solo exhibitions by Adrián Villar Rojas. The featured works included materials such as bread, fruit, vegetables, a lobster tail, and a then eight-year-old sponge cake.

The starting point for the projects created by Villar Rojas and his team is often site-specific—indeed, interaction with the site is taken to its utmost limits. The exhibition at Moderna Museet, entitled Fantasma, was such a case.1 A central theme was interrelated with the museum context, highlighting issues of memory and the shaping of objects, inclusion and exclusion of objects and audiences, and the question of who determines and who has access to museum contents. The self-consuming practice of the artist confronted the museum’s traditional perspective of eternity.

The space was designed to partly disorient visitors in order to heighten their awareness of the museum’s features. Villar Rojas wanted to create what he described as “a crazy passage, where people would wonder what is going on or what went wrong in terms of display of objects, use of walls, use of textures, use of the space” (). Typical museum features and details were distorted by narrowed passages, raised podiums, and faux wall panels. Slick, pristine, shiny surfaces and illuminated showcases were used. These features surrounded objects consisting of various kinds of organic and inorganic materials, partly in decay, creating a contrasting setting that highlighted and commented on the works as museum pieces. In the film introducing the exhibition, Villar Rojas stated how he wanted to reflect on the concept of documents and on the objects as documents, and what that means to him specifically, since most of his earlier works no longer exist ().

For this project, adhering to a core feature of museum practice, Villar Rojas for the first time chose to reinstall works from earlier exhibitions. “This show is a big mirror, in a way, of these wrinkled objects,” he noted (). The objects were effectively “elevated” to museum documents, and the vulnerable, originally temporal pieces, in this setting, challenged classical museum terms like permanence, inherent value, treatability, and transportability (fig. 18.2).

Initial Challenges

On arrival in Stockholm, some of the objects were found to be infested by insects—mainly biscuit beetles (Stegobium paniceum)—and mold. Since the exhibition was to take place amid the permanent collection, rather than in the more separate galleries that usually host the temporary exhibitions, the infestation risk called for an immediate action plan. An entomologist and a mold expert were consulted. Due to the short time available prior to installation, the infested parts were treated with Vikane gas (sulfuryl fluoride). Mold spores were analyzed before further exposure to museum staff or visitors was allowed. Fortunately, the examination showed low concentrations and no toxic spores.

During preparation and through the exhibition period there was an open dialogue between the conservators and the artist regarding the display of objects. Dilemmas, big or small, were attended to with perfect attention to minute detail by the Villar Rojas studio. For example, there were discussions about vulnerable pieces that could not be secured or protected, and about the handling of debris and losses, namely whether these should be removed or retained. Images were exchanged and mutual decisions made. Conservators had to work outside their comfort level, accepting change and losses, and the artist had to be understanding toward necessary treatments and limitations of display.

The long exhibition period, April to October, required daily monitoring by conservators. It went well, the only exception being that of recurring minor infestations, which were heat treated in the conservation department.2

Acquisition: Pedazos de las personas que amamos

Two of the more challenging works in Fantasma were acquired by Moderna Museet after the exhibition. Despite the inherent museological challenges, the works were selected because they were central to Fantasma and also represent key characteristics of how the artist addresses the time-based, the ephemeral, and the cinematic in sculpture. During the exhibition, the main aim was to control and stop infestations. The options available for this were limited given that the works were on view. With the later acquisition came long-term conservation concerns related to the works’ essential nature. Should they be allowed to decay, or could they be approached in a more traditional way?

Untitled (fig. 18.3) is a cake originally baked in 2006, which at the time of acquisition was nine years old. The materials are described as sponge cake, marzipan, milk chocolate, and plastic, and it measures 18 × 50 × 51 cm. It was baked by the artist’s aunt and was originally part of Pedazos de las personas que amamos (Pieces of the People We Love), a large installation shown in 2007 at arteBA, a contemporary art fair in Buenos Aires. The original installation was arranged on a large wooden table and depicted the universe from God’s point of view, with objects following a life cycle ending with an intentional death (fig. 18.4). The cake was the final and pivotal scene of the tragedy, a miniature landscape in the shape of a cemetery where the heartbroken main character dies inside a giant robot shell, surrounded by small crosses (, 9).

Figure 18.3

Figure 18.3 Figure 18.4

Figure 18.4Villar Rojas never intended for the cake to be saved after this initial installation, but it was collected by the artists’ parents and brought to their hometown of Rosario, Argentina, where it was stored in a warehouse for eight years before traveling to Stockholm. In Fantasma it was displayed in a wall vitrine with a rounded inner back wall, behind glass and on a white underlit (LED) surface of acrylic (fig. 18.5).

Figure 18.5

Figure 18.5Since entering the Moderna Museet collection, its visual appearance has not changed significantly, but the cake shows heavy signs of passing time. Colors are faded, and dimensions and textures show dramatic changes, with cracks and many losses. Past infestations are visible as bore holes, and dead beetles are fused to the surface—easy to mistake, at first, for sprinkles.

Acquisition: Los teatros de Saturno III

Los teatros de Saturno III (The Theaters of Saturn III, fig. 18.6) consists of eighty-five different parts, each with different measurements and made of diverse materials, including plants, bread, fish, sneakers, electronics, and a lobster tail. The objects were originally shown at kurimanzutto in Mexico City in 2014, where they were part of the larger installation Los teatros de Saturno (fig. 18.7). Components of this installation were produced by the Villar Rojas team in a temporary workshop in Mexico. Found objects were combined with organic material and foodstuffs; for instance fresh vegetables and fruits were molded into shapes using gesso. The resulting objects were spread out over the gallery floors, which during the exhibition were covered with soil, and they changed by growing, rotting, and decaying throughout the exhibition period (fig. 18.8).

Figure 18.6

Figure 18.6 Figure 18.7

Figure 18.7 Figure 18.8

Figure 18.8In Fantasma, a selection of 284 objects were shown, including epoxy figures from the series The Work of the Ocean.3 They were put on a large white podium 1.55 meters high. Half of the surface holding the objects was painted, and the other half was opaque white acrylic lit from below with LED lights. These two very different presentations show that the artist does not have a static approach, and that objects can transform according to context.

After the exhibition, the installation was split into four parts, of which Moderna Museet acquired one, consisting of eighty-five objects. Shortly after the acquisition, the work was shown at Moderna Museet Malmö, a subsidiary of the Stockholm museum. In dialogue with Villar Rojas, it was decided that the objects should be exhibited on a podium of the same construction and height as in Fantasma, but one-fourth the original size. The surface was still half underlit opaque white acrylic, and half a painted surface. Even if the same type of presentation was chosen for the exhibition in Malmö, the artist is open to other display constellations, with these possibilities still to be determined.

Objects from Los teatros de Saturno are in different stages of decay. The most significant and dramatic changes, mainly to the organic parts, occurred already during the exhibition at kurimanzutto, but degradation is an ongoing process, albeit now a lot less dramatic. Vegetables, fruits, and other matter were hard to recognize upon arrival at Moderna Museet, and so documentation from the production in Mexico was used to trace and identify the materials of the objects.

Today, both of the artworks that were acquired are stored in the conservation department, continuously being monitored for infestation while awaiting a complete conservation plan.

Ethics: Accepting Change?

When an ephemeral work enters a museum collection, its status needs to be determined, and the artist’s intention identified. Ephemeral works can vary in nature, and different approaches can be adopted. There is a wide spectrum of possible conservation strategies, from a total non-intervention policy to the possibility of replacing components.

Villar Rojas has described his works as diachronic objects that transform and mutate over time (). Time and life spans are important in his practice. Parallel to this is his interest in what will be the last artwork on the planet, and an engagement in the aging of the objects and their conservation care: “They are so fragile; they need so much care. That’s another of my extreme fantasies: maybe the children of the children of the people I work with will still have to be restoring and preserving and taking care of these objects, whichever are left. It will be an endless battle against time” ().

At the creation point, both works were clearly ephemeral, and degradation was originally a natural part of their life cycle (). Different circumstances made the continuation of their existence possible, and with the reinstallation in the Stockholm exhibition, their lives took a new turn. Between the two venues, the identity of the Los teatros de Saturno objects went through a change from actively performing as “mutant sculptures” living in the soil at kurimanzutto in 2014 to passive highlighted museum pieces at Moderna Museet in 2015. This transformation has implications for future care and points to the importance of defining the identity of the objects.

As the artist put it: “The Moderna Museet is the very first moment where I am introducing objects that were previously shown in another exhibition. And I think that was the key motor, the engine, of this show” (). The habit of reusing materials from former works was not new to the artist, but the Stockholm exhibition was the first time that objects as complete entities were stored and reinstalled in their same configuration. The museum context and the way the theme of the exhibition related to this will be an important factor in any future reinstallations, and should be taken into account in the decision making and conservation approach.

Defining the nature of and temporal aspects governing the ephemerality of these objects is not straightforward. Could the conservation care and activities be incorporated in their life cycle, given the particular context in which they were exhibited? One could claim that fundamental, defining factors of the objects’ existence changed when they became museum artifacts in the Fantasma context, and that this continues into their future life at Moderna Museet, thus making conservation care a part of their natural change. The dialogue between artist, museum curators, and conservators regarding any larger decisions is ongoing. A thorough artist interview was completed on December 4, 2019. It will be an important tool for any decisions regarding the definition of objects and how to proceed with conservation care.

Preparations for Storage and Future Display

Regardless of the guidelines that will be set, preparations for storage needed to be made, and insects are in no way acceptable in storage spaces. A project was initiated to investigate options for long-term storage, with the primary aim being to avoid infestation. The project is a collaboration with the Heritage Science laboratory at the Swedish National Heritage Board through the Guest Colleague program. This program offers scientific support, including relevant instrumentation and analyses, to assist conservators working with public collections. The project is ongoing and is planned to be presented in the near future.

The project investigates the prerequisites for anoxic storage, which early in the process was suggested as a sustainable option to avoid infestations. This would also slow all deterioration caused by oxygen-related processes. Normally this is a desired effect for conservation, but in this case one might not want this disturbance to degradation processes, due to the work’s intentionally ephemeral qualities.

Another concern was how to detect and predict emissions from the materials—the objects themselves but also the materials chosen for storage and packing (). For the Los teatros de Saturno objects, an effort has been made to identify the different plastic materials to determine how best to store the items and minimize their negative effects on one another. This has primarily been done using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). A study of volatiles and emissions is planned in order to see if there is a need for additional absorbents in anoxic storage. Dye-coated pH-sensitive A-D strips have been used to detect acidic gases. Still, many of the individual objects involve multiple materials, and so a complete identification of all constituents does not take away from the fact that a strategy for co-storing materials is needed. Therefore, the possibility of adding adsorbents to the storage system in order to mitigate emissions has been considered, with activated charcoal likely being the best suited. To minimize storage space, the objects need to be stored together. Storage boxes will be transparent to facilitate monitoring.

The final storage solution should leave the objects visible, facilitate monitoring without opening, offer minimal contact points to the vulnerable objects, and avoid unnecessary handling. The packing materials need to be long-term, sustainable, and not emit any gases that could be harmful to the collection. All the potential packing materials are therefore being Oddy tested as a starting point in determining what is suitable (, 9).4

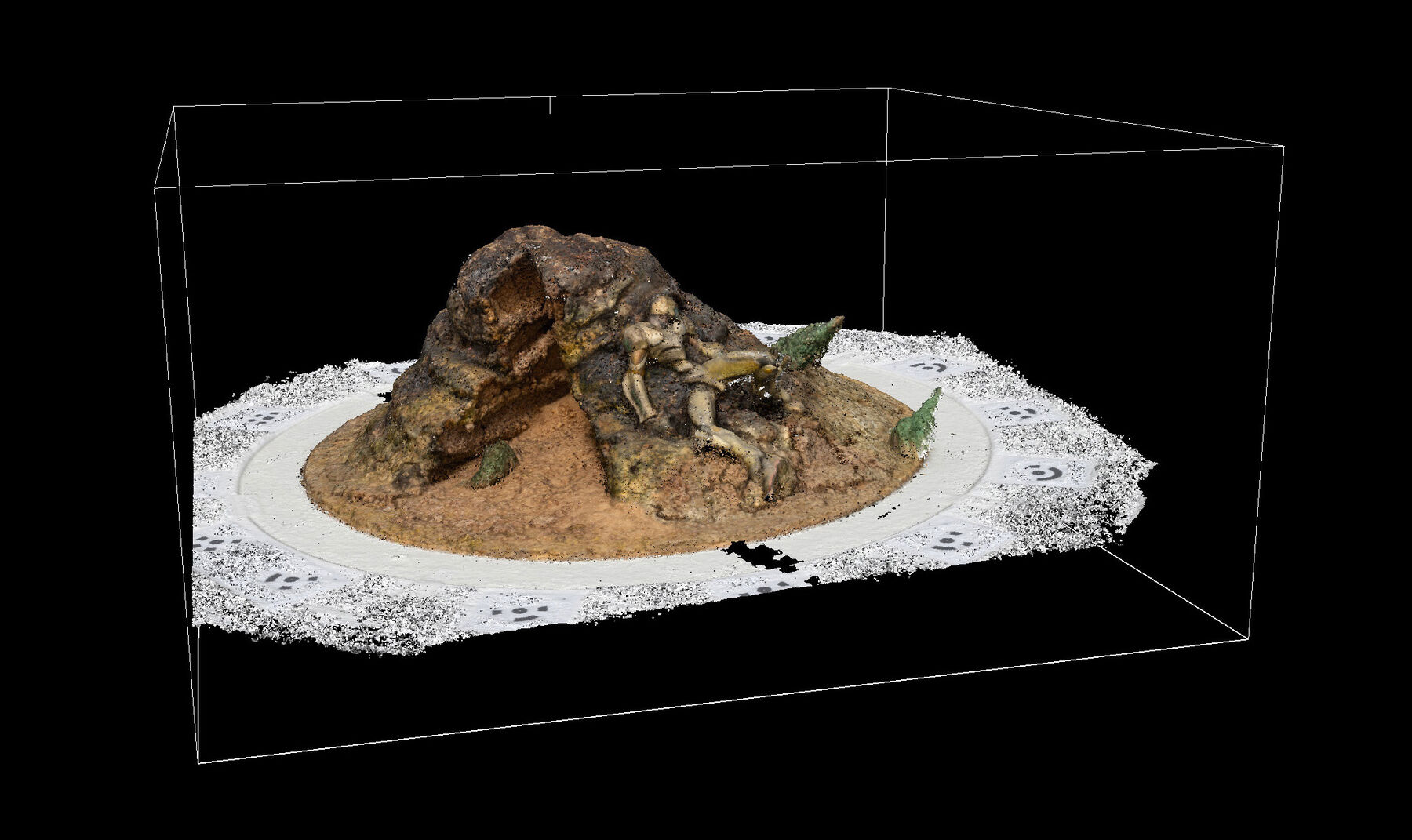

Possibilities for documenting changes in dimension, shape, and color are also being sought. A first step was to perform photogrammetry to generate a 3D model of the sponge cake (fig. 18.9). Care was taken to document the performance of the photogrammetry in order to accurately replicate the investigation at a later time, so as to visualize dimensional and color changes; specifically, small hidden markers were placed under the base plate of the cake to facilitate comparative photogrammetry in the future. This method, if successful, could be applied to all the Villar Rojas objects.

Figure 18.9

Figure 18.9A planned X-ray examination will, in the best scenario, give us structural information and make it possible to see the impact of insects on the inner structure.

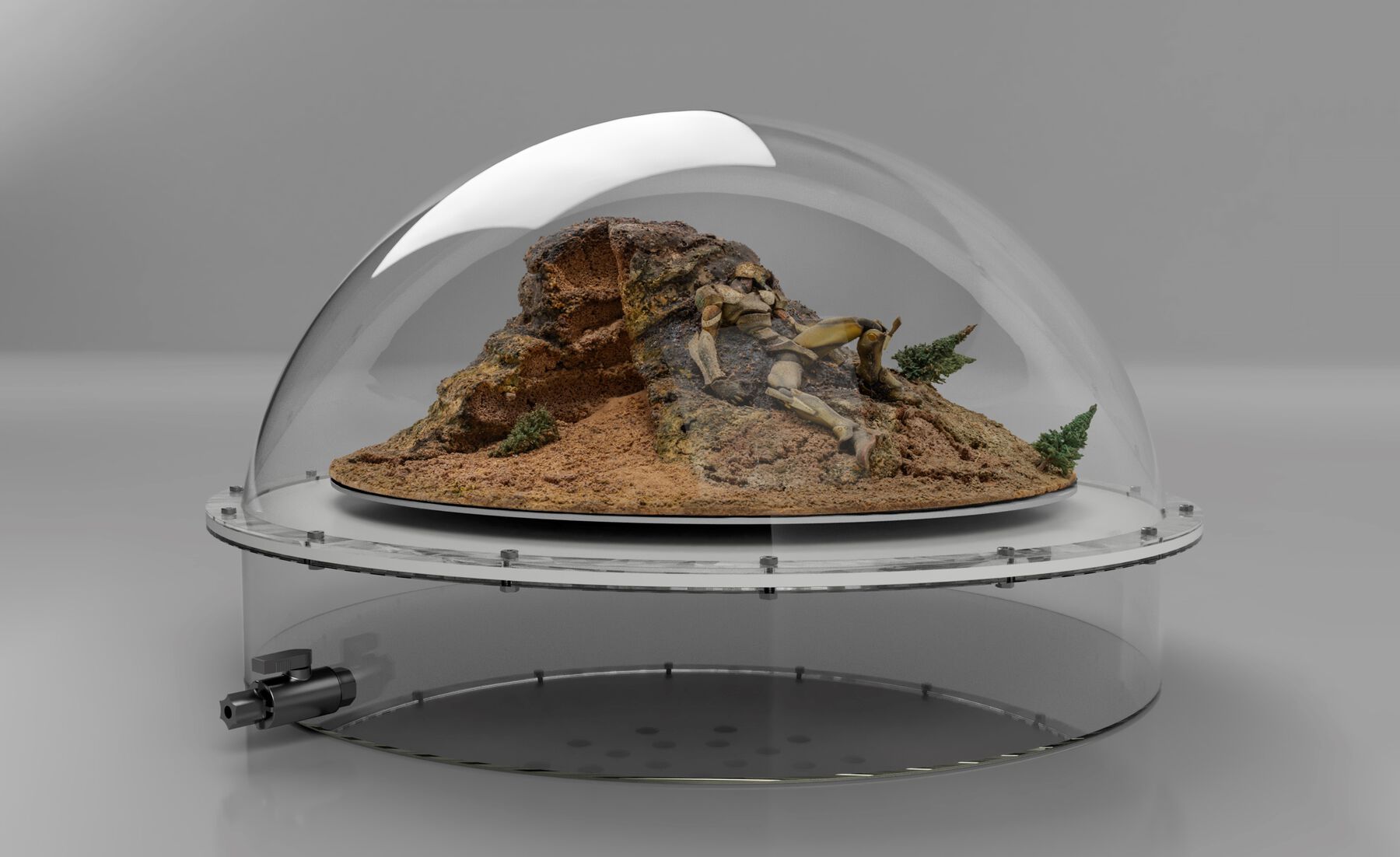

Development of a Showcase Prototype

Together with the Swedish National Heritage Board, the conservators started planning for an oxygen-free storage solution for the cake. A transparent hemisphere shape was chosen to minimize the amount of air and to facilitate monitoring. When a digital sketch was rendered, it was reminiscent of a hibernation pod, a recurring reference in Villar Rojas’s work (fig. 18.10). There were sci-fi connotations and suggestions of a survival sphere connecting it to the last-art-object-on-Earth thoughts, and to the aesthetics of later Villar Rojas projects.5 This, in turn, led to the idea of a combined storage and showcase solution, a way to permanently keep the piece in an oxygen-free environment.

Figure 18.10

Figure 18.10A plan for this was drawn and a digital mockup produced. In this, the work is placed on a white acrylic support. The bottom part holds the devices monitoring and adjusting the air quality: relative humidity, temperature, pH, and oxygen levels. A port will make it possible to extract small amounts of air for control measurements. When exhibited, the white acrylic support can be integrated to hide the bottom part housing the controls. Since it is transparent, it can still be lit from underneath, as in the Fantasma installation. The initial presentation to the artist and to collection curators elicited positive responses. The first brief was well received, and the digital sketch will be a useful tool.

The hemisphere raises many questions. Can we keep the piece oxygen-free without compromising the intent of the artist? In the event that the permanent hemisphere is found to be acceptable, how will it affect the integrity of the work? Will it in fact make it a new piece, or will it remain the same work dated 2007? Had we, in the moment we presented the sphere, stepped out of our roles as conservators and affected the future display and perception of this work? Again, continued conversations with Villar Rojas in order to more closely define the work are crucial to any further decisions.

Conclusion

Caring for the works by Villar Rojas in the Moderna Museet collection is a work in progress. Research into the development of these works has indicated that their ephemeral nature might have changed when entering the museum, from being active, performing, deteriorating objects to more passive artifacts. This eventual redefinition will open possibilities for conservation measurements that at first were considered impossible.

Conservation and collection management must be open to the fact that the identity and appearance of artworks can change over time and prepared to redefine approaches. The acquired works are examples of objects being both materially transformed and affected by different presentations. Professional roles are also shifting. Conservation crossed traditional professional borders by taking an active part in the life span and aesthetic future of the Pieces of the People We Love cake by presenting the idea of the permanent showcase. Villar Rojas and collection curators have had and will hopefully continue to have active roles in the development of the conservation strategy.

Notes

Curated by Lena Essling and Matilda Olof-Ors, April 25–October 25, 2015. ↩︎

Inner temperature 60℃ for two hours. ↩︎

Exhibition by Adrián Villar Rojas at De 11 Lijnen, Oudenburg, Belgium, 2013. ↩︎

The Oddy test is an accelerated corrosion test that involves putting a small amount of material in a sealed enclosure at 60℃ and 100 percent relative humidity for twenty-eight days, together with metal coupons (silver, lead, and copper), and observing the effect of the material emissions on the metals. ↩︎

Examples include The Theater of Disappearance, Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles (2017), and The Theater of Disappearance, National Observatory of Athens (2017). ↩︎

Bibliography

- Canosa and Norrehed 2019

- Canosa, Elyse, and Sara Norrehed. 2019. Strategies for Pollutant Monitoring in Museum Environments. Visby, Sweden: Swedish National Heritage Board. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1324224/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Essling and Villar Rojas 2015

- Essling, Lena, and Sebastián Villar Rojas. 2015. “Fantasma Adrián Villar Rojas.” Exhibition booklet. Edited by Maria Morberg. Stockholm: Moderna Museet.

- Thickett and Lee 2004

- Thickett, D., and L. R. Lee. 2004. “Selection of Materials for the Storage or Display of Museum Objects.” British Museum Occasional Paper 111. London: British Museum.

- Villar Rojas 2014

- Villar Rojas, Adrián. 2014. Filmed interview by Jordan Bahat at kurimanzutto, Mexico City. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=qJEE-yNCHQM.

- Villar Rojas 2015

- Villar Rojas, Adrián. 2015. Filmed interview by Lena Essling, Moderna Museet, Stockholm. https://youtu.be/g6yv6qKJjG4.

- Villar Rojas 2017

- Villar Rojas, Adrián. 2017. Filmed interview by Elina Kountouri, Neon, Athens, June 3, 2017. https://player.vimeo.com/video/224171178.

- Villar Rojas 2018

- Villar Rojas, Adrián. 2018. “In the Studio: Adrián Villar Rojas.” Interview by Gabriel Roland. Collectors Agenda, August 20, 2018, https://www.collectorsagenda.com/en/in-the-studio/adrian-villar-rojas.