7. “To Isis the Great, Lady of Benevento”: Privately Dedicated Egyptian Obelisks in Imperial Rome and the Twin Obelisks of Benevento Reedited

- Luigi Prada

Assistant Professor of Egyptology, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University - with an appendix by Paul D. Wordsworth

Associate Lecturer in Islamic Archaeology, University College London

[…] sunt enim gemini obelisci beneventani […] magno in pretio habendi.

—Luigi Maria Ungarelli, 1842

When we think of Egyptian obelisks and ancient Rome, what immediately comes to mind are the large monoliths, inscribed with hieroglyphs, that the Romans relocated from Egypt to their imperial capital city, monuments that were already ancient at the time of their removal, having originally been erected by Egyptian pharaohs in the second and first millennia BC.1 But besides these ancient monuments, obelisks of two other kinds were erected by Roman emperors. The first type consists of uninscribed obelisks, valued for their mass and devoid of any kind of hieroglyphic inscriptions, with the most renowned example being the Vatican obelisk, now standing at the center of Piazza San Pietro.2 The other, and probably the most intriguing kind, comprises obelisks with hieroglyphic inscriptions expressly commissioned and dedicated by Roman emperors, sporting texts composed for the occasion in Middle Egyptian—that is, the archaic, classical phase of the Egyptian language, which had fallen out of common use already in the second millennium BC but was traditionally still employed in Egypt, on account of its historical prestige, for monumental hieroglyphic inscriptions. Two such inscribed Roman obelisks are known today:3 the Pamphili obelisk, erected by Domitian (r. AD 81–96) and now in Piazza Navona, with texts celebrating the emperor and the Flavian dynasty, and the Barberini obelisk, carved by order of Hadrian (r. AD 117–38) and now located in the Monte Pincio gardens, with inscriptions focused on the life, death, and deification of his companion Antinous.4 Egyptian hieroglyphs could therefore be used—albeit exceptionally—in official inscriptions ordered by imperial authority, as an alternative to the two mainstream scripts (and languages) in which official texts were normally issued across the Roman Empire: Latin and Greek.5

It is perhaps less well known that the erection of obelisks in the Roman Empire did not occur exclusively at the behest of the emperor. Some, of more reduced size than their royally ordered counterparts, were in fact commissioned by influential private citizens with sufficient financial means. Thus, in the year AD 166, under the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, a centurion named Titus Aurelius Restitutus dedicated a pair of obelisks in Aswan, at the southern frontier of Egypt.6 Neither of them survives, hence we do not know what these obelisks looked like and whether they were uninscribed or displayed any hieroglyphic texts.7 Nevertheless, the Latin inscription carved on the base of one of the two—which is all that survives of these monuments—makes it clear that these two obelisks (oboliscos duos, l. 4) were erected by Restitutus to Jupiter and at least another deity (the text is lacunose, but this must have been either Juno—as is most likely—or Isis) “[for] the health and victory of our emperors” ([pro] salute et victoria imp(eratorum) n(ostrorum), l. 2), seemingly a reference to their recent victory in the Parthian war.8

Luckily, there are also cases in which privately commissioned obelisks, and not just their pedestals, have survived into our times. In some instances they could be decorated with so-called pseudo-hieroglyphic inscriptions. Examples include a small obelisk now in Florence,9 which carries an incomprehensible text formed by a patchwork of phrases and individual hieroglyphic signs in most cases inspired by genuine earlier Egyptian inscriptions, and a fragment of another obelisk, this time in Benevento,10 in which the carvings intended to represent hieroglyphs are purely fanciful signs, having no actual direct resemblance or connection to the ancient Egyptian script.11 Less frequently, however, these private obelisks could also be decorated with meaningful hieroglyphic inscriptions, bearing texts expressly commissioned for the occasion, as a nonroyal counterpart to imperial commissions such as the Pamphili and Barberini obelisks cited above. The fragmentary Borgia and Albani obelisks and the much better preserved twin obelisks of Benevento belong to this remarkable category, and it is on these monuments that the present paper will focus.12 Before delving into a closer analysis of these monuments, however, a methodological issue needs to be addressed.

When it comes to ancient Rome’s interest in all things Egyptian, modern scholarship has typically traced a clear line between actual “Egyptian” antiquities that the Romans imported from Egypt (be they statues, reliefs, obelisks, or other artifacts) and “Egyptianizing” objects produced in Italy to emulate Egyptian products. Running in parallel to this classification, a similar distinction has also been drawn between those monuments that bear legible, meaningful hieroglyphic inscriptions and those that sport illegible pseudo-hieroglyphs. This is a classification imposed by modern scholars upon the ancient evidence, however, and would not have been necessarily valid in the eyes of the Romans. Recently Molly Swetnam-Burland has convincingly argued that such a rigid taxonomy can actually be misleading when trying to understand Roman interest in and approaches to ancient Egyptian culture and its artistic production, since it risks uprooting the objects from their historical context and therefore fails to grasp their cultural biographies.13 Thus, when dealing with Roman obelisks, we should not necessarily assume that monuments inscribed with legible hieroglyphic texts such as those of Benevento appeared intrinsically more Egyptian to a Roman audience than those covered in pseudo-hieroglyphs, like the Florentine specimen. No Roman citizen—and very few native Egyptians, to be sure—would have been able to read a hieroglyphic inscription, be it genuine or “gibberish,” and thus its value would have been primarily symbolic, through the connection that (pseudo-)hieroglyphs established with ancient Egypt and its traditions, real or perceived. It is therefore only apt that, when referring to a hieroglyphic text written on a papyrus scroll, Apuleius should use the phrase litterae ignorabiles, or “unknown characters,” in his novel of Isiac salvation.14

While accepting this framework, I would, however, argue that Roman obelisks inscribed with legible hieroglyphic texts—be they imperial or private commissions—still occupy a distinct place in the study of Roman aegyptiaca.15 Indeed, they invite us to push our criticism even further and to question the common equivalences often implicitly traced in modern scholarship between: (a) original Egyptian imports = legible hieroglyphs and (b) Egyptianizing monuments = pseudo-hieroglyphs. Since they were commissioned by Roman patrons and, at least in some cases, were carved in Italy (likely examples include the Borgia and Albani obelisks, discussed below, but also Domitian’s Pamphili obelisk),16 they have generally been regarded as Egyptianizing artifacts. Yet, rather than being covered in pseudo-hieroglyphs, they make a creative use of the ancient Egyptian language and script and thus attest to the evolution of Roman as much as of Egyptian royal ideology and religious thought: for the Roman emperor was ultimately also Egypt’s pharaoh, and the only individuals able to produce hieroglyphic inscriptions at the time were members of the Egyptian priesthood. These monuments thus operated simultaneously on two levels. Surely they held an immediate symbolic function associating them with Egypt and the perceived lore of its ancient traditions, as did any other Egyptianizing artifact. But on top of this they also communicated a specific, programmatic message in their inscriptions. In them, to quote Swetnam-Burland, there is no dichotomy between an Egyptian “creation” and a Roman “reuse”; nor is there a competition between a “symbolic” and a “literal” meaning: for their creation was simultaneously Egyptian and Roman, and their meaning was intended from the start to work on both a symbolic and a literal level.17

We must also remember that these obelisks’ inscriptions were not written purely according to the whimsy of Egyptian priests. Far from it, they were prepared following the instructions of their powerful dedicators, based at least in part on original drafts in Greek or Latin, and their preparation surely must have entailed a serious investment of money and time, which was bound to be much bigger than anything required for comparable aegyptiaca that were instead covered in gibberish inscriptions. Necessarily, the Roman sponsors of such inscribed monuments were therefore fully conscious of the specific meaning of the hieroglyphic carvings incorporated into their dedications and would have had an interest in advertising it. In fact, I even wonder whether the hieroglyphic inscriptions of these novel obelisks would have been made accessible to the Roman public, at least in some cases, by means of Latin translations. These need not necessarily have been published as accompanying epigraphs to the obelisks—something of which we have no evidence—but could have been easily circulated in other, more perishable forms, perhaps as opuscula. To be sure, we do know that at least one Greek version of the hieroglyphic inscriptions of an Egyptian obelisk dating to pharaonic antiquity and reerected in Rome by Augustus (r. 27 BC–AD 14)—the Flaminio obelisk—existed and was read in antiquity.18 If translations of the inscriptions of ancient pharaonic obelisks reerected in Roman Italy could be published and disseminated, mostly as an erudite curiosity, would it not make all the more sense to suppose that something alike was done for obelisks containing custom-made inscriptions immortalizing living figures—be they the reigning emperor and/or a private dedicator—who had an active interest in having the details of their Egyptian architectural feats known? After all, modesty and subtlety were not virtues in which the Romans of the imperial age excelled.

All of the above is what makes these artifacts both Roman and Egyptian from the very moment of their conception and thus objects worthy of investigation for the Roman historian and the Egyptologist alike. It is thus no surprise that inscribed Roman obelisks should attract special attention among scholars and that the detailed study of their inscriptions and the information carried therein should be a key component in their historical assessment. This is why I feel justified in singling out these artifacts as pertaining to a specific and indeed important class among aegyptiaca and in devoting a study to a particular subgroup among them—that of inscribed Roman obelisks dedicated by private individuals. So let us now discuss the actual specimens of this corpus, that is, the Borgia, Albani, and, in special detail, Benevento obelisks.

The Borgia and Albani Obelisks

These two red granite obelisks, of which only fragments survive, are preserved in museum collections in Palestrina and Naples (Borgia)19 and in Munich (Albani).20 According to their inscriptions—which, as expected, were drawn up in Middle Egyptian—they were both dedicated by the same individual, a Titus Sextius Africanus,21 but the badly damaged state in which they survive means that we can hardly say anything more about them, apart from the fact that they were probably erected in the first century AD in honor of an emperor whose name and titles partly survive in fragmentary cartouches. Scholars normally recognize this emperor as Claudius (r. AD 41–54), but this remains uncertain, as can immediately be seen from the transliterations and translations of the inscriptions.22

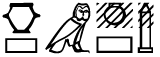

Borgia Obelisk

(Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Palestrina and Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli)23

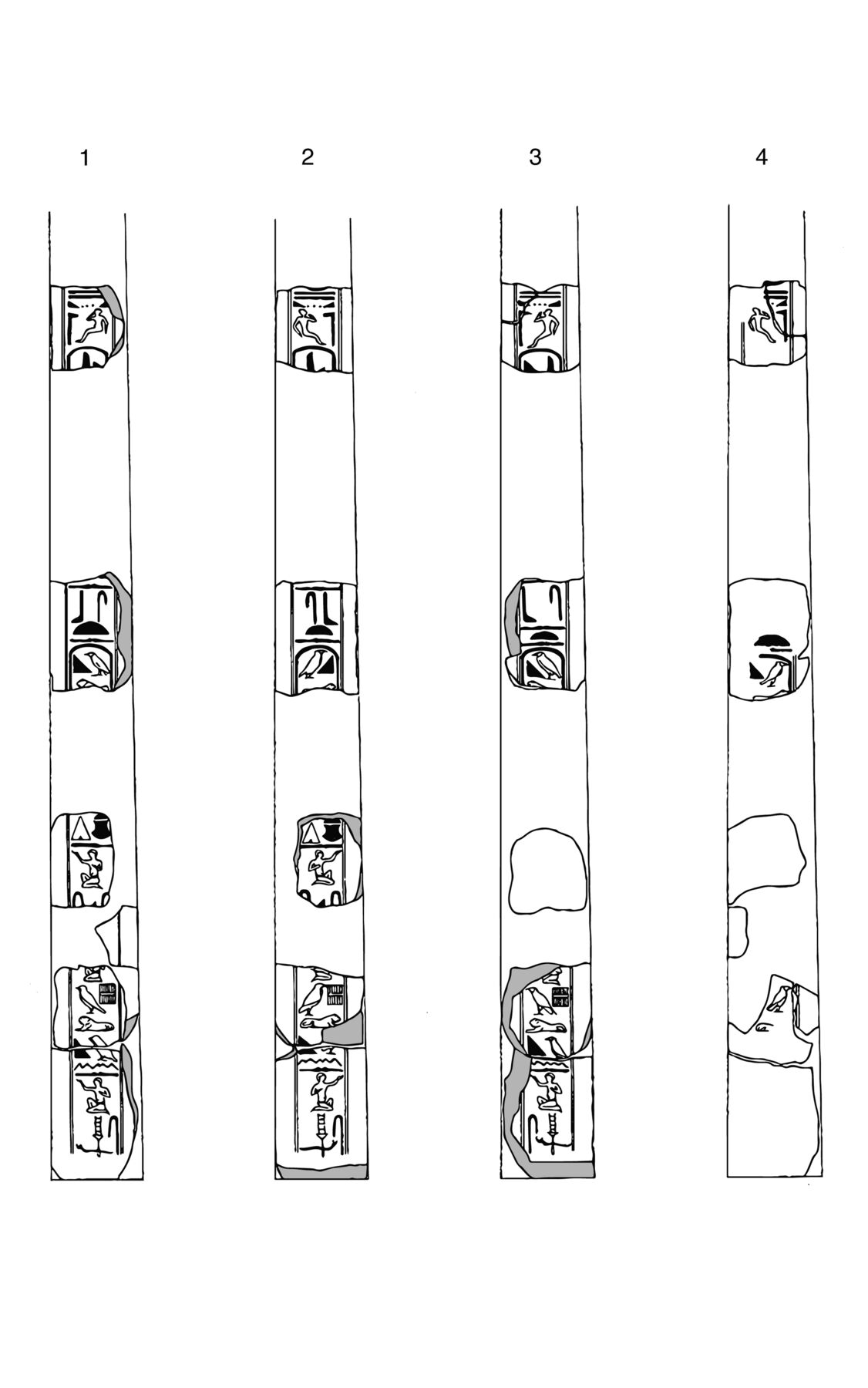

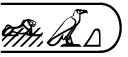

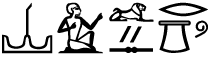

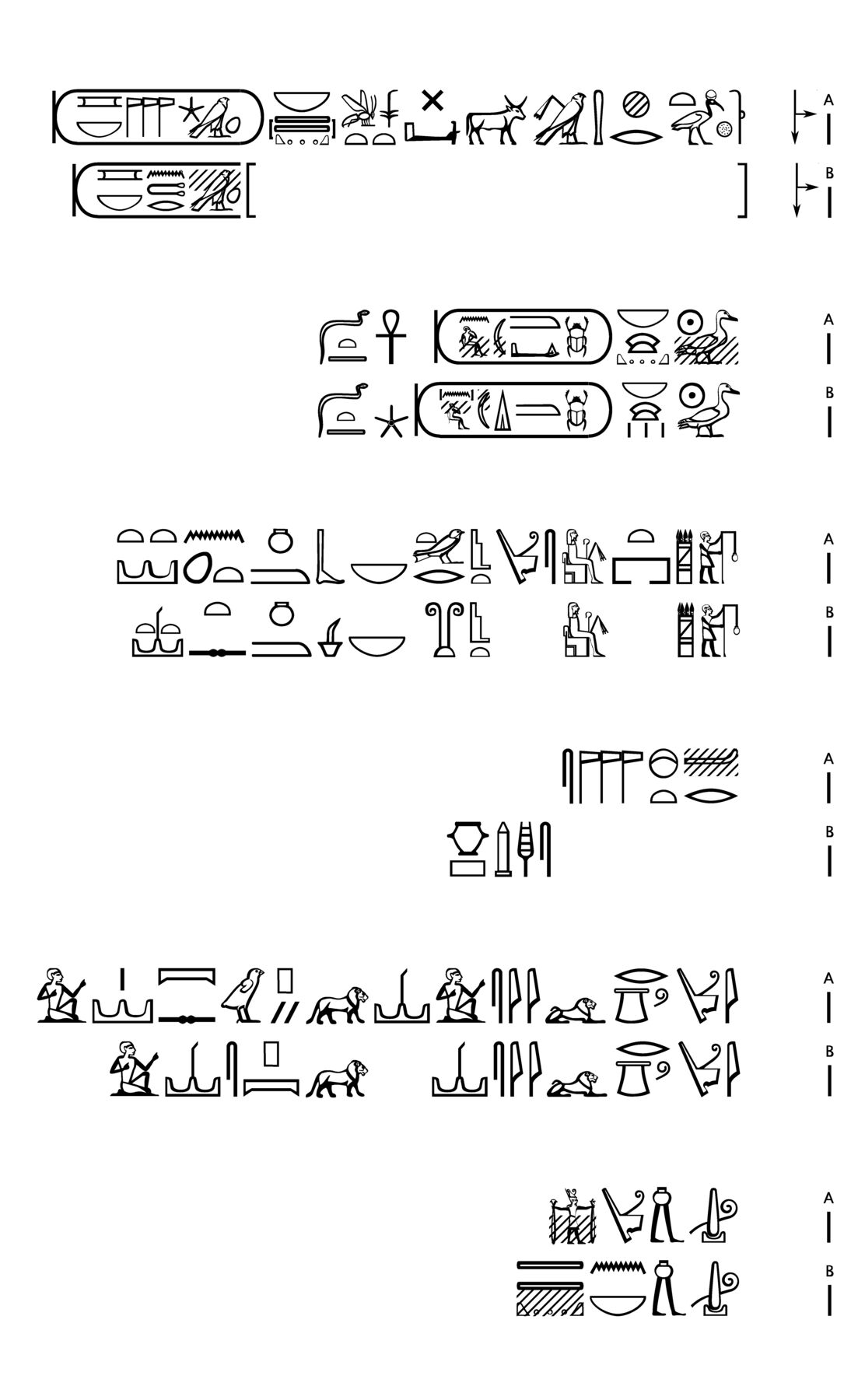

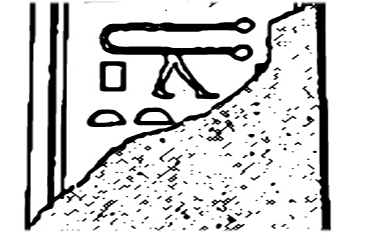

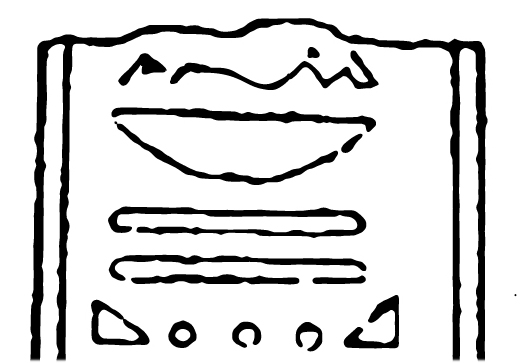

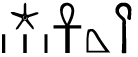

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1 Figure 7.2

Figure 7.2 Figure 7.4

Figure 7.4| Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|

| [. . .] ˹nb˺ tA.wy sA nTr ˹QI˺[. . .] %bsts QA˹R˺[. . .] &its ˹%qs˺[ts] AprqAns saHa=f <sw> | […] the Lord of the Two Lands, the Son of the God, … […] the Augustus, … […]. (As for) Titus Sex[tius] Africanus, he erected <it> (sc., this obelisk).24 |

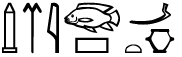

Albani Obelisk

(Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich)

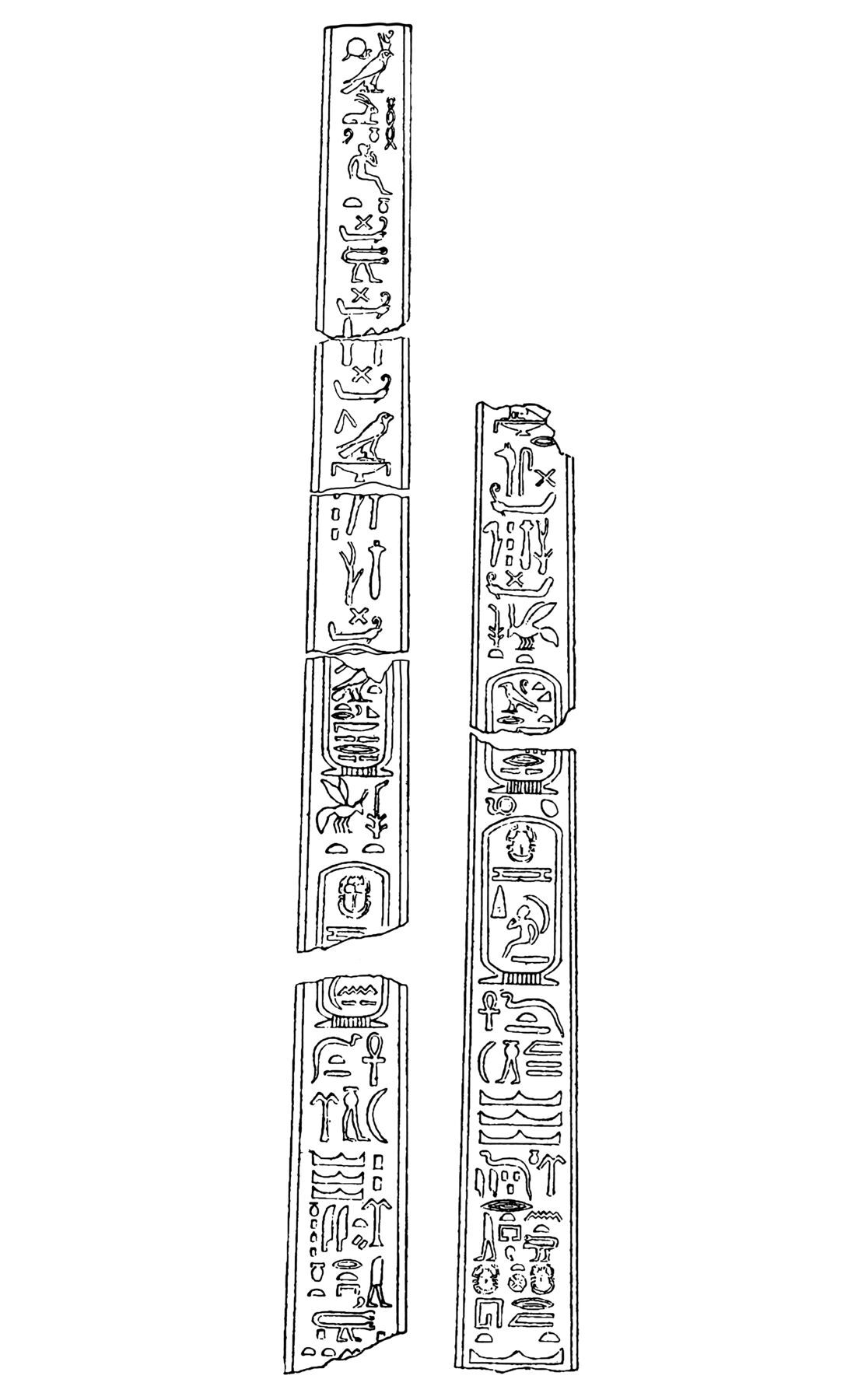

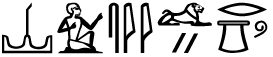

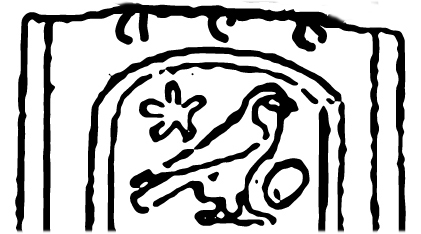

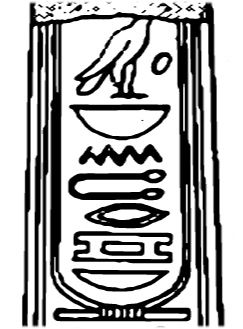

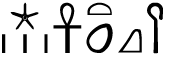

Figure 7.5

Figure 7.5 Figure 7.7

Figure 7.7| Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|

| [. . . K]˹Y%˺R% %bsts &its %qsts AprqAns sxn.n{.t}=f s(w) r [. . .] | [… C]aesar, the Augustus. (As for) Titus Sextius Africanus, he dedicated it (sc., this obelisk)25 … […] |

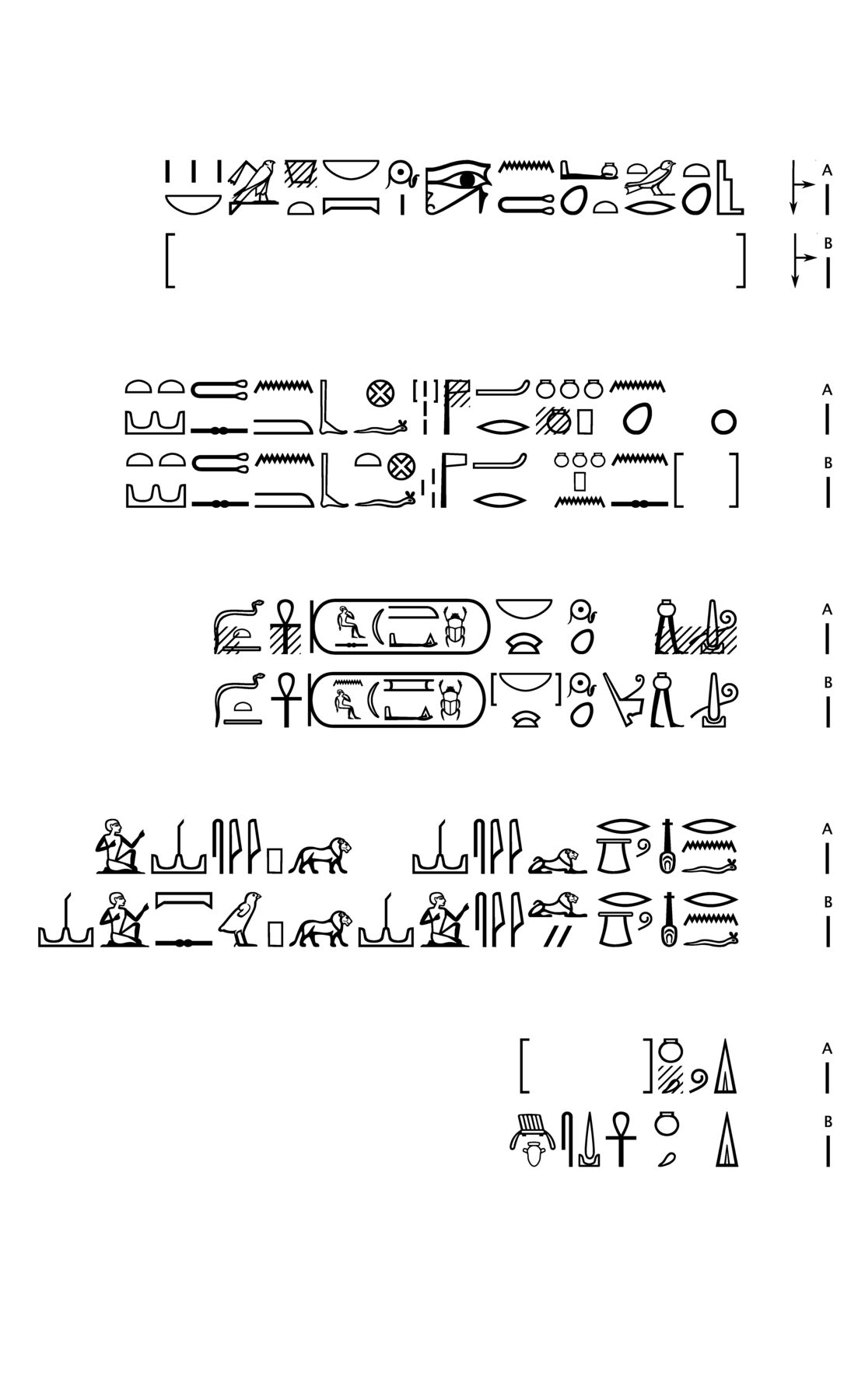

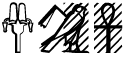

The name of Claudius has been reconstructed from the Borgia fragments, which bear at the beginning of their second cartouche the signs  QA˹R˺[. . .]. In modern studies, these have typically been interpreted as Q˹L˺A[. . .] (the sign of the recumbent lion

QA˹R˺[. . .]. In modern studies, these have typically been interpreted as Q˹L˺A[. . .] (the sign of the recumbent lion  having both the phonetic value r and l), hence Claudius.26 In parallel, scholars have read in the Borgia fragments’ first cartouche only the sign

having both the phonetic value r and l), hence Claudius.26 In parallel, scholars have read in the Borgia fragments’ first cartouche only the sign  i, typically understanding this ˹I˺[. . .] to be the beginning of the title autokrator (i.e., emperor).27

i, typically understanding this ˹I˺[. . .] to be the beginning of the title autokrator (i.e., emperor).27

It was only recently that Elisa Valeria Bove highlighted that the top part of a  q seemingly also survives in the first cartouche, which she thus read ˹QI˺[. . .] and considered to be a writing of Caius (hence assigning the obelisks to the reign of Caligula—r. AD 37–41—rather than Claudius) or, alternatively, of the generic imperial title Caesar.28 As for the second cartouche, she understood QA˹R˺[. . .] as A<W&>Q˹R˺[&R], that is, as part of a defective writing for autokrator.29 Indeed, Bove’s new epigraphic record of the Borgia fragments held in Palestrina is correct: as a new inspection of the section has confirmed, the reading ˹QI˺[. . .] in the first cartouche is indisputable.30 Nevertheless, I find Bove’s understanding of QA˹R˺[. . .] as a heavily defective writing of autokrator to be deeply unlikely. For all we know, and on account of the peculiar forms that Egyptian royal titularies can take in Roman inscriptions such as this, QA˹R˺[. . .] might, in fact, even pertain to an unusual writing of the title Germanicus.31 Overall, I think it is impossible to state with any degree of certainty which emperor was originally named in these cartouches, which is why I leave their content unread in my translation.

q seemingly also survives in the first cartouche, which she thus read ˹QI˺[. . .] and considered to be a writing of Caius (hence assigning the obelisks to the reign of Caligula—r. AD 37–41—rather than Claudius) or, alternatively, of the generic imperial title Caesar.28 As for the second cartouche, she understood QA˹R˺[. . .] as A<W&>Q˹R˺[&R], that is, as part of a defective writing for autokrator.29 Indeed, Bove’s new epigraphic record of the Borgia fragments held in Palestrina is correct: as a new inspection of the section has confirmed, the reading ˹QI˺[. . .] in the first cartouche is indisputable.30 Nevertheless, I find Bove’s understanding of QA˹R˺[. . .] as a heavily defective writing of autokrator to be deeply unlikely. For all we know, and on account of the peculiar forms that Egyptian royal titularies can take in Roman inscriptions such as this, QA˹R˺[. . .] might, in fact, even pertain to an unusual writing of the title Germanicus.31 Overall, I think it is impossible to state with any degree of certainty which emperor was originally named in these cartouches, which is why I leave their content unread in my translation.

Similar uncertainty has also affected the understanding of the private dedicator’s name. Most interpreters agree on seeing in the inscriptions’ &its %qsts AprqAns a rendering of Latin Titus Sextius Africanus,32 but others have suggested transliterating the cognomen as PAlAqns and reading in it Palicanus, a name already attested in the epigraphy of Palestrina.33 Nevertheless, based on the order in which the signs most frequently occur on both the Borgia and the Albani obelisks, I am of the opinion that Africanus remains the preferable reading.34

Perhaps more remarkably, the very relationship between the two obelisks is uncertain. They were undoubtedly commissioned by the same patron (whose name appears, identically, on both monoliths) and carved in the same workshop (their epigraphy is the same). Since the fragments of the Borgia obelisk were unearthed in Palestrina (ancient Praeneste), however, while the Albani obelisk section is thought to originate from Rome, it has generally been assumed that they were not twin obelisks erected at the same site.35 This may well be the case, but I believe it is also possible that both were originally a pair in Palestrina and that one of the two was moved, in antiquity or later, to nearby Rome.36

The discovery of the Palestrina fragments in the area of the sanctuary to Fortuna Primigenia (and the known assimilation between this goddess and Isis) has also led a number of scholars to suggest a connection between these two obelisks and the cult of Isis.37 As attractive and plausible as this view is, it must remain, however, only a hypothesis, for sadly no mention of any Egyptian deity, let alone of Isis, survives in either of the obelisks’ inscriptions.

To complete this brief overview of the Borgia and Albani obelisks, a few words ought to be devoted to the nature of their hieroglyphic inscriptions. From an epigraphic viewpoint, they present a number of idiosyncrasies (recurrent inversions of signs and awkwardly shaped hieroglyphs—note especially the unusual width of the  t sign in most of its occurrences) that are generally believed to be diagnostic of hieroglyphic inscriptions carved in Italy rather than in Egypt, by craftsmen who were not conversant with the traditional proportions of the signs that they were reproducing.38 Also remarkable are some peculiarities in the text of the inscriptions, like the choice of the unusual phrase sA nTr “the Son of the God” in lieu of the traditional pharaonic epithets used to introduce the cartouches,39 and some apparent syntactic oddities, such as the name of the dedicator being anticipated before a verb in the suffix-conjugation and (in the case of the Borgia obelisk) the absence of a direct object referring to the obelisk. In consideration of the poor condition in which both obelisks and their texts survive, it is hard to pass a firm judgment, and surely the perplexities of scholars who saw in these inscriptions a corrupt use of Middle Egyptian, influenced by the rules of Latin syntax, are in part justifiable. As I argued before, however, I do not share these perplexities,40 and I still believe that the texts of both obelisks can be explained in terms of standard Egyptian grammar (even despite the seeming omission of the direct object in the Borgia obelisk). Whatever our judgment of the linguistic quality of these inscriptions, their texts must have been composed by an Egyptian priest, after some general instructions in Latin or Greek prepared according to Africanus’s wishes. Said priest would have been the only available professional figure with a knowledge of Middle Egyptian, the archaic language phase traditionally used for such monumental inscriptions, and of the hieroglyphic script.41 I would therefore be inclined to ascribe any issues found in the inscriptions to the Roman carver(s) and their potential misunderstandings (and/or omissions) of the signs that they were meant to reproduce on the stone rather than to the Egyptian priest’s linguistic competence.

t sign in most of its occurrences) that are generally believed to be diagnostic of hieroglyphic inscriptions carved in Italy rather than in Egypt, by craftsmen who were not conversant with the traditional proportions of the signs that they were reproducing.38 Also remarkable are some peculiarities in the text of the inscriptions, like the choice of the unusual phrase sA nTr “the Son of the God” in lieu of the traditional pharaonic epithets used to introduce the cartouches,39 and some apparent syntactic oddities, such as the name of the dedicator being anticipated before a verb in the suffix-conjugation and (in the case of the Borgia obelisk) the absence of a direct object referring to the obelisk. In consideration of the poor condition in which both obelisks and their texts survive, it is hard to pass a firm judgment, and surely the perplexities of scholars who saw in these inscriptions a corrupt use of Middle Egyptian, influenced by the rules of Latin syntax, are in part justifiable. As I argued before, however, I do not share these perplexities,40 and I still believe that the texts of both obelisks can be explained in terms of standard Egyptian grammar (even despite the seeming omission of the direct object in the Borgia obelisk). Whatever our judgment of the linguistic quality of these inscriptions, their texts must have been composed by an Egyptian priest, after some general instructions in Latin or Greek prepared according to Africanus’s wishes. Said priest would have been the only available professional figure with a knowledge of Middle Egyptian, the archaic language phase traditionally used for such monumental inscriptions, and of the hieroglyphic script.41 I would therefore be inclined to ascribe any issues found in the inscriptions to the Roman carver(s) and their potential misunderstandings (and/or omissions) of the signs that they were meant to reproduce on the stone rather than to the Egyptian priest’s linguistic competence.

When it comes to the content of the texts of these obelisks, two defining elements stand out, despite their fragmentary condition. The first is the mention of the emperor, which almost certainly occurred in the context of a celebration of the reigning monarch.42 The second is the identity of the private patron who dedicated the obelisks, that is, Titus Sextius Africanus. As we will see shortly, these two elements are essential components in the inscriptions of privately dedicated inscribed Roman obelisks, and they both feature prominently also in the more complex texts of the twin obelisks of Benevento.

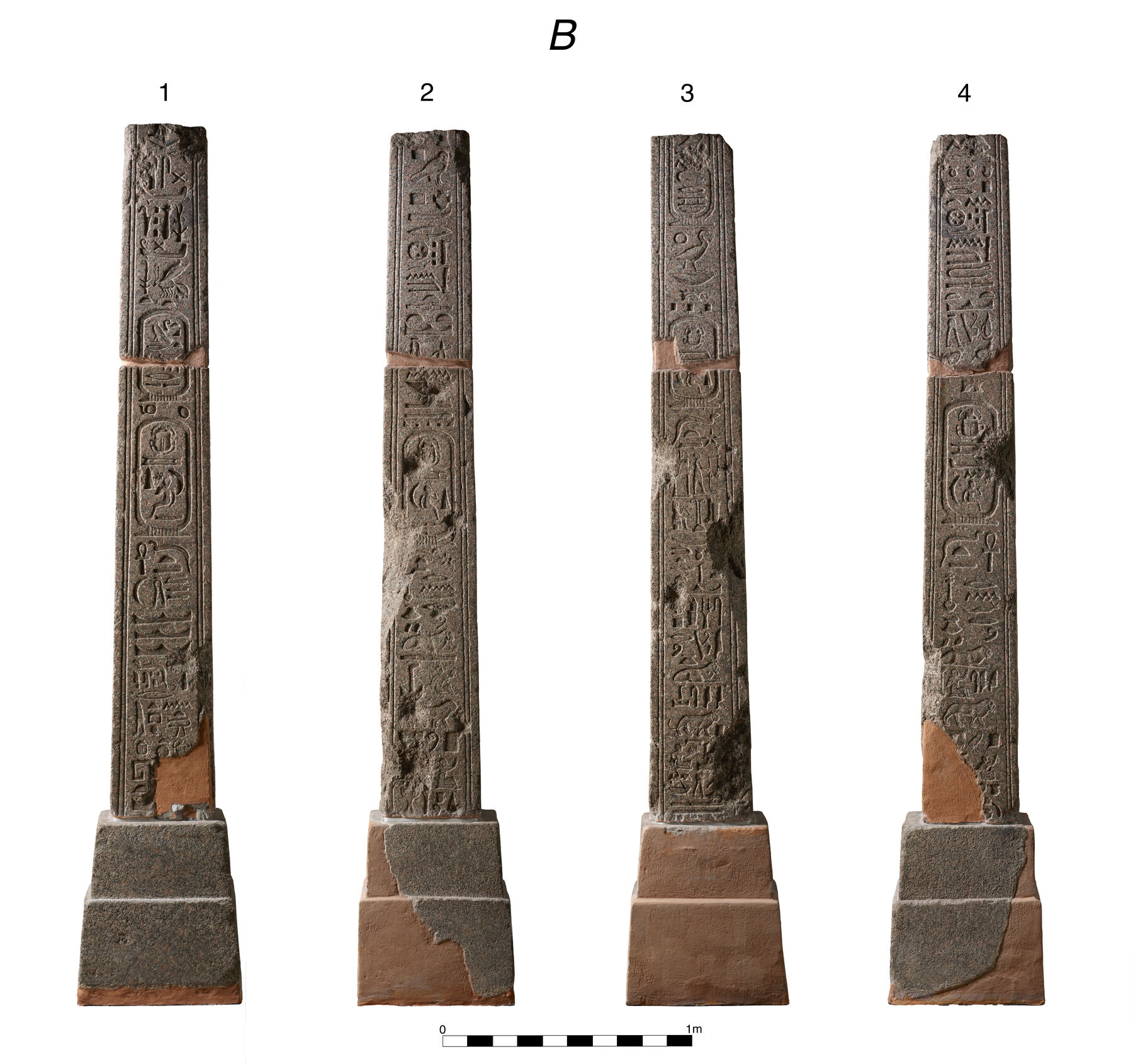

The Benevento Obelisks

These red granite twin obelisks probably stood in front of the Iseum of Benevento.43 Compared to the sorry state of the Borgia and Albani obelisks, they are substantially better preserved. One of them, traditionally labeled obelisk A, survives almost in its entirety, missing only its pyramidion, and now stands in a public square of Benevento, Piazza Papiniano. Its full shaft has been reassembled from five fragments,44 for a combined height of 4.12 meters; once its ancient stepped plinth (which is 0.77 meter high) and the modern pyramidion (0.5 meter) are also included, the total is 5.39 meters.45 Its twin, obelisk B, lacks the upper third of its shaft, including its pyramidion. The remainder has been reassembled from two fragments, reaching a combined height of 2.8 meters or, with the inclusion of its ancient plinth (which is 0.7 meter high), of 3.5 meters.46 It is now preserved in Benevento’s Museo del Sannio (inv. 1916).47 Since the original bases of both obelisks are preserved, it is interesting to note that neither shows any kind of inscribed dedication in Latin (or Greek).48 This is unlike the case of the Aswan obelisks dedicated by Titus Aurelius Restitutus, at least one of which bore a Latin inscription on its plinth, elucidating the reason for their dedication and the identity of their commissioner. The bases of the Borgia and Albani obelisks are not extant; hence we do not know how they would have compared.

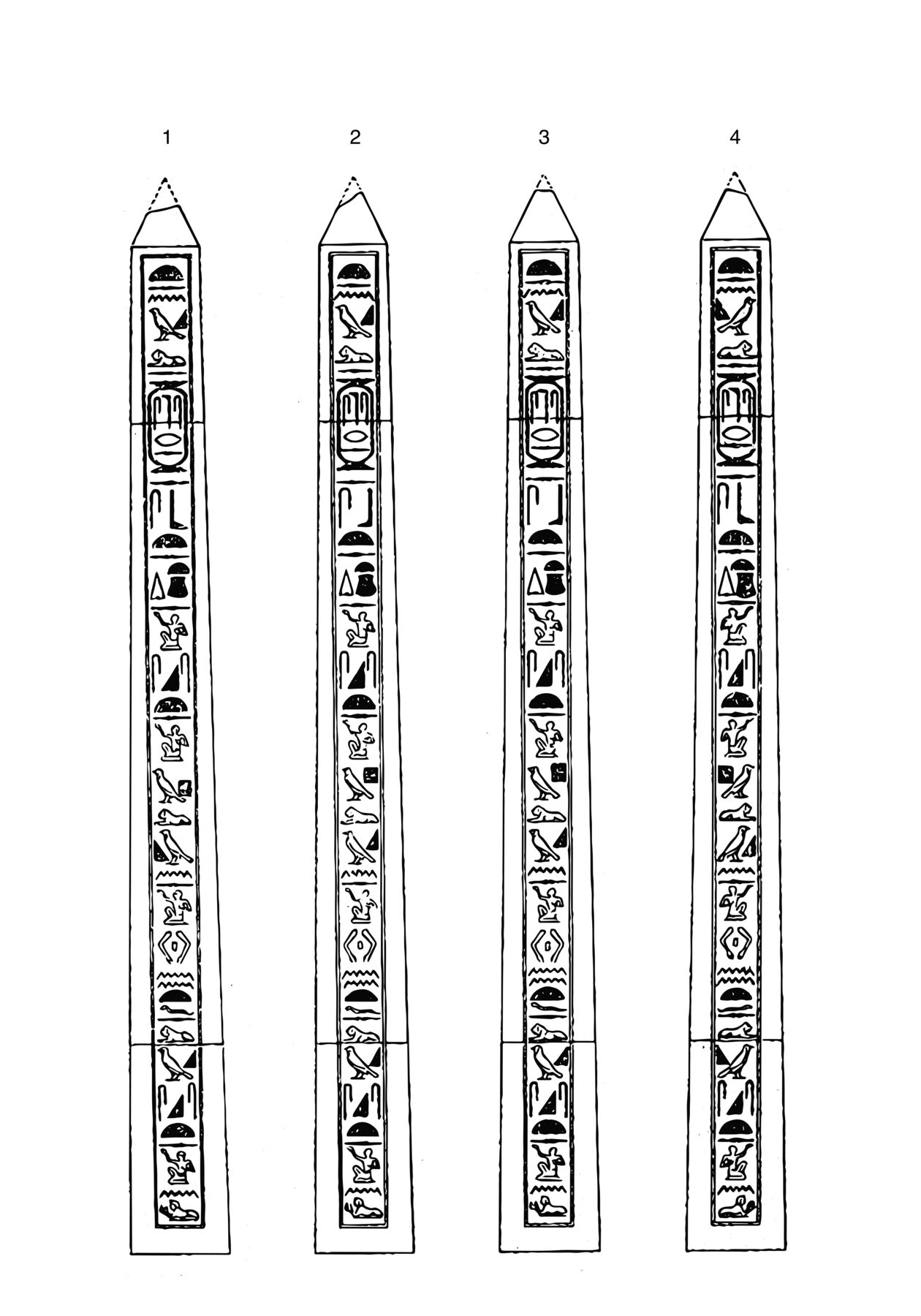

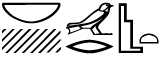

Figure 7.8

Figure 7.8 Figure 7.9

Figure 7.9From their Middle Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions, we learn that the Benevento obelisks were erected as part of the construction of the city’s Iseum by a local notable, whose name was Rutilius Lupus,49 in the eighth year of the reign of Emperor Domitian, that is, in AD 88/89.50 They were dedicated to Isis in celebration of the emperor, seemingly to commemorate his successful return from a military expedition, if we understand the text correctly (more on this in the following commentary, note 10 to side 2).

These twin obelisks, or fragments thereof, have been known to scholars since the early days of Egyptology.51 The first full scientific treatment appeared shortly after the discovery, in 1892, of the top section of obelisk A, which finally restored this obelisk’s inscription to its original length and provided a complete text for these twin monuments. Thus, in 1893 Adolf Erman and Ernesto Schiaparelli independently published two studies of the inscriptions.52 The latter was unfortunately laden with mistakes both in the copying of the hieroglyphs and in the text’s translation—as pointed out by Erman in a later, expanded study of the obelisks—and is hence completely superseded.53 Instead Erman’s work—especially his second study, from 1896—is still consulted with profit to this day and in fact remains the only full philological treatment of the inscriptions of both obelisks available to date. Other complete translations of the obelisks’ texts have appeared since Erman’s, but in these cases scholars have generally preferred simply to translate the complete inscriptions of obelisk A, noting the few passages that diverge from those of B.54 Such translations have been produced by various authors, including Hans W. Müller,55 Michel Malaise,56 Erik Iversen,57 Ethelbert Stauffer,58 Vito A. Sirago,59 Rosanna Pirelli,60 Marina R. Torelli,61 Laurent Bricault,62 Kristine Bülow Clausen,63 and the present writer.64 In many cases, however, these and other authors—a number of whom were not Egyptologists but ancient historians—were unable or unwilling to engage directly with the original hieroglyphic texts and thus reproduced more or less verbatim earlier translations, relying mainly on those by Erman, Müller, Malaise, and Iversen, with varying degrees of success.65 The resulting situation, with multiple and significantly divergent published translations, many of which depend on secondary literature, has—understandably—engendered confusion and many a misconception as to the exact content of the inscriptions, contributing to the problems that we are still facing in making sense of them.

Perhaps the clearest example of such a potential for confusion concerns a problematic phrase found in the inscriptions,  wDA ini, the interpretation of which can radically change our understanding of the text.66 Whereas Erman, Müller, and Malaise understand it as an allusion to the safe return of Domitian from a military expedition, Iversen instead sees in it a title of the obelisk’s dedicator, namely, an Egyptian rendering of the Latin word legatus. The two interpretations are mutually exclusive. Yet they can be found merged as if mutually compatible in later studies that depend on these scholars’ publications, which results in a complete misrepresentation of the ancient evidence.67 Nor is this the only problematic and disputed passage in the inscriptions: divergent readings, for instance, also impact the name of the dedicator, as we will see in the commentary below.

wDA ini, the interpretation of which can radically change our understanding of the text.66 Whereas Erman, Müller, and Malaise understand it as an allusion to the safe return of Domitian from a military expedition, Iversen instead sees in it a title of the obelisk’s dedicator, namely, an Egyptian rendering of the Latin word legatus. The two interpretations are mutually exclusive. Yet they can be found merged as if mutually compatible in later studies that depend on these scholars’ publications, which results in a complete misrepresentation of the ancient evidence.67 Nor is this the only problematic and disputed passage in the inscriptions: divergent readings, for instance, also impact the name of the dedicator, as we will see in the commentary below.

It is on account of such difficulties with the text and of the increasing interest that aegyptiaca (and Isiaca) like these obelisks are enjoying in present scholarship—among Egyptologists and scholars of the classical world alike—that I think it not only worthwhile but also necessary to offer a reedition of the inscriptions of these obelisks.68 This reedition provides a new standardized copy of the hieroglyphic text, a new translation, and, for the first time, also a transliteration of the Egyptian original (for the reader’s convenience, the transliteration and translation are offered again, as a continuous text, in appendix A). It draws together more than a century of relevant scholarship and its often wildly divergent interpretations of the inscriptions, sieves through these different layers of understandings (and misunderstandings), and offers a commentary that intends to be relevant and accessible to scholars from both academic backgrounds—Egyptology and ancient history—trying to make crucial issues of Egyptian language and epigraphy that directly impinge on the meaning of the text understandable also to nonspecialists.69 My ultimate aim is that such a study will clear the slate from a series of misconceptions about these monuments, present (and justify) the best possible readings, and clarify what we can understand for sure from the inscriptions and what instead remains problematic or hypothetical. Thus, it will hopefully become a platform for colleagues to engage with and from which to develop further studies on these unique obelisks.

Another contribution of this study is a new, improved epigraphic copy of the obelisks’ inscriptions, combined with detailed photographic documentation (for which, see appendix C). Originally my research took as a starting point Erman’s published facsimiles, which were derived from squeezes (paper molds) taken from the originals and had consequently always been assumed to be reliable epigraphic records.70 Indeed, none of the intervening studies since Erman’s time have ever looked again at the original epigraphy. In a good number of instances, however, it became apparent to me that his copies—albeit admirable for the time and circumstances in which they had been created—are inexact, something that I could definitively confirm when I inspected the obelisks in person. Thus, I have provided a new facsimile of the inscriptions (as an edited version of Erman’s), following a study of newly captured digital images and, most importantly, a collation with the originals. Specifically, I inspected both obelisks during a visit to Benevento in July 2020, having previously already examined obelisk B in August 2018, on the occasion of the exhibition Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

While highlighting issues with Erman’s copy, this new epigraphic study has simultaneously confirmed, however, how valuable his and other historic documentation of these obelisks remain. First, it revealed that some of the details inaccurately reproduced in Erman’s facsimile—concerning both the inscriptions and the position of the fractures between the different obelisks’ fragments—are instead correctly registered in a much earlier copy, the first modern epigraphic record of the Benevento obelisks, which was published in 1842 by Luigi Ungarelli.71 Though itself not exempt from mistakes, this earlier record turns out to be at times more faithful to the original and possibly also to preserve details of the inscriptions that had become damaged or lost half a century later, in Erman’s time. Albeit long forgotten, Ungarelli’s copy is therefore still worth consulting.72 Second, this new epigraphic survey has also shown that both obelisks suffered considerable damage sometime during the twentieth century, I believe during World War II (through the heavy bombings to which Benevento was subjected and/or the occupation of the city by the Allies in 1943). Especially in the lower section of obelisk B (which, at the time, was standing outdoors in Piazza Papiniano, wrongly combined with the upper fragments of obelisk A), several and substantial parts of the inscriptions that were still extant in Erman’s time are, sadly, now lost.73 Nineteenth-century copies like Ungarelli’s and Erman’s therefore remain an irreplaceable asset to modern scholars.

To conclude, I offer here a few practical notes about the following reedition. Any particularly significant difference between Ungarelli’s and Erman’s copies and, more importantly, between Erman’s facsimile and my own will be discussed individually in the textual commentary. The reader will also find a systematic overview of such differences in appendix B, which, on the one hand, compares Ungarelli’s and Erman’s copies and, on the other, highlights the points of Erman’s facsimile that I was able to correct or improve upon. I made the conscious choice not to mark in my new facsimile damage that has occurred since the time of Erman, for this would have entailed the obliteration of a significant amount of epigraphic information, especially for obelisk B. My copy is therefore not a facsimile of the monuments in their present condition but rather a corrected and enhanced copy of Erman’s, closely documenting these artifacts in their end-of-nineteenth-century state. Any modern damage, however, is fully recorded and can be observed in the photographic documentation published here, which was taken at the Getty in 2017 (obelisk B) and in Benevento in 2020 (obelisk A). Such damage is also flagged, whenever appropriate, in the textual commentary.

My standardized copy of the hieroglyphic texts is the first published since Erman’s 1896 study. To assist the reader and intuitively show my interpretation of the inscription, the mutual positioning of some signs has been reordered, in those cases in which inversions or odd arrangements occur in the original. Whenever my standardized hieroglyphic transcription significantly disagrees with Erman’s, this is flagged in the commentary.

This reedition follows the traditional order in which the inscriptions have been numbered since Erman’s first study, moving clockwise around the obelisks beginning from the side containing the royal titulary of Domitian.74 This face is generally considered to come first, since its inscriptions are the only ones mirroring each other in terms of the orientation of their hieroglyphs, with obelisk A’s signs facing right and B’s signs facing left.75 All other sides have their inscriptions facing right, according to the preferred direction of Egyptian indigenous scripts. Indeed, I believe we can suggest a further, in this case ideological, reason why side 1 must have taken pride of place and faced the visitors who approached the temple: for it is the only face of the monoliths that names and celebrates exclusively the emperor, Domitian, while making no mention of the private dedicator, whose name instead appears, repeatedly but less prominently, on the other three sides of each obelisk.

Finally, while obelisk B is located in a museum and its sides are therefore not permanently related to the cardinal points, it is worth recording the approximate orientation of the faces of obelisk A, in its current setting in Piazza Papiniano. This is as follows: 1 = south side; 2 = west side; 3 = north side; 4 = east side.

Commented reedition of the inscriptions on the Benevento obelisks

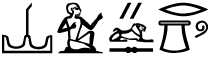

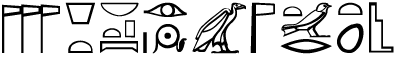

Side 1

Summary

The focus is on the celebration of Emperor Domitian. It includes his full royal titulary in traditional Egyptian style, that is, his five names,76 followed by a reference to his military might as displayed by the tributes gathered in Rome from all over the empire and even from beyond its borders. The mention of his military feats may be either generic praise or a precise allusion to the emperor’s return from his Dacian and Germanic campaigns in AD 89.

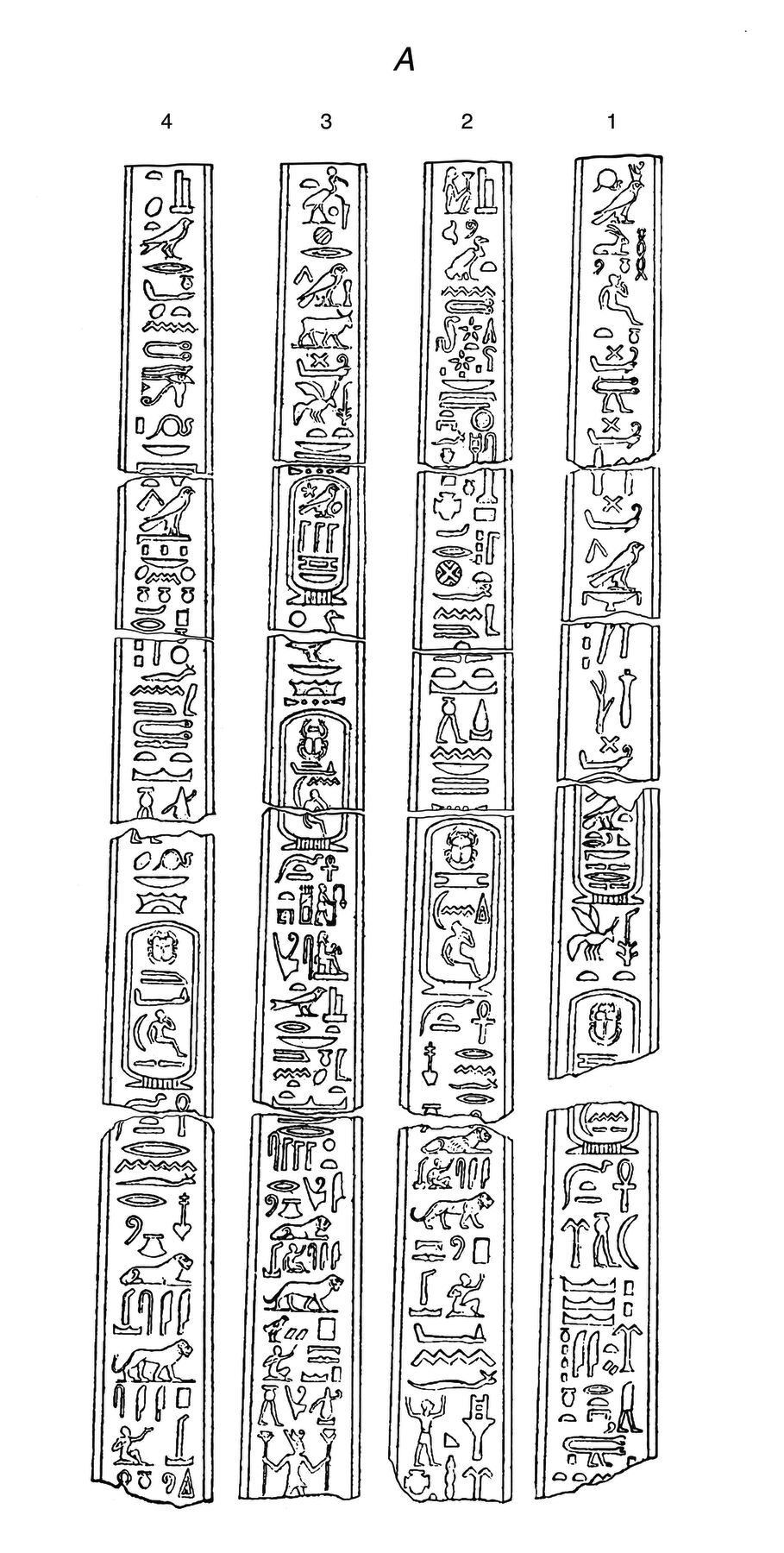

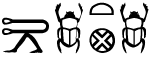

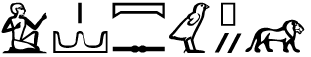

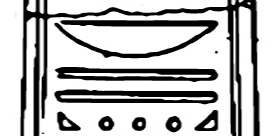

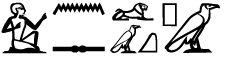

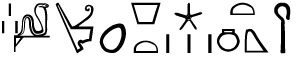

Figure 7.10

Figure 7.10 Figure 7.11

Figure 7.11 Figure 7.12

Figure 7.12 Figure 7.13

Figure 7.13| Obelisk A (Piazza Papiniano)77 | Obelisk B (Museo del Sannio) |

|---|---|

| ↓→ @r Hwn n<x>t(?) <nb.ty> iTi ˹m sxm˺ bik nbw ˹wsr rnp.w(t)˺ aA nxt <nsw.t bi.ty> ˹AW˺&QR&R K%R% nsw.t bi.ty &˹M˺[&]IN% anx D.t xbi in(.w) m tA.wy xAs.wt m ntyy.w r iy.t=f n.t Xnw [!r]˹m˺ | ←↓ [. . .] ˹bik˺ nbw wsr rnp.w(t) aA nxt nsw.t bi.ty AW&QR&[R] K˹Y%˺R% sA Ra &M&IN% anx D.t xbi in(.w) m tA.wy xAs.wt m nDy.w r iy.t=f n.t Xnw !rm |

| The Horus “Str<o>ng(?) Youth,” <the Two Ladies> “He Who Conquers through Might,” the Golden Falcon “Powerful of Years and Great of Triumph,” <the King of Upper and Lower Egypt> Emperor Caesar, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Domi[t]ian, ever-living, he who collects tribute from the Two Lands and the subjugated foreign countries to his sanctuary(?) of the capital city, [Ro]me. | […] the Golden Falcon “Powerful of Years and Great of Triumph,” the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Empero[r] Caesar, the Son of Re Domitian, ever-living, he who collects tribute from the Two Lands and the subjugated foreign countries to his sanctuary(?) of the capital city, Rome. |

Notes

(1) n<x>t(?): The text has nt, which makes no sense. As Domitian’s Horus name appears in his Pamphili obelisk, side 1, as  Hwn qn “Valorous Youth,”78 most interpreters have quite radically emended our inscription’s nt

Hwn qn “Valorous Youth,”78 most interpreters have quite radically emended our inscription’s nt  into qn

into qn  ,79 a reading that has the additional advantage of connecting Domitian’s Horus name with that of earlier Ptolemaic rulers, confirming a link observed elsewhere in his titulary.80 Overall, the royal titulary of Domitian as it appears in the Pamphili and Benevento obelisks is, however, significantly different; hence there is no reason to consider the Pamphili obelisk’s version as a necessary parallel here. Neither is yet another variant to this Horus name, Hwn nfr “Perfect Youth” (found in Domitian’s titulary in the temple of Dush), particularly helpful.81 Another reading proposed in earlier scholarship suggests understanding our nt as a writing of nt(r) < nTry “Divine,” but this must certainly be excluded on account of phonetic reasons and of the determinatives accompanying this word,

,79 a reading that has the additional advantage of connecting Domitian’s Horus name with that of earlier Ptolemaic rulers, confirming a link observed elsewhere in his titulary.80 Overall, the royal titulary of Domitian as it appears in the Pamphili and Benevento obelisks is, however, significantly different; hence there is no reason to consider the Pamphili obelisk’s version as a necessary parallel here. Neither is yet another variant to this Horus name, Hwn nfr “Perfect Youth” (found in Domitian’s titulary in the temple of Dush), particularly helpful.81 Another reading proposed in earlier scholarship suggests understanding our nt as a writing of nt(r) < nTry “Divine,” but this must certainly be excluded on account of phonetic reasons and of the determinatives accompanying this word,  , which clearly describe an adjective connected with the ideas of strength/conflict.82 I therefore prefer tentatively to read these signs as n<x>t, for this has the advantage of being a substantially less invasive emendation than qn, while still matching the concept expressed in the determinatives (qn and nxt are, in fact, virtual synonyms).83 Note that elsewhere in these inscriptions, nxt appears in the shorter writings

, which clearly describe an adjective connected with the ideas of strength/conflict.82 I therefore prefer tentatively to read these signs as n<x>t, for this has the advantage of being a substantially less invasive emendation than qn, while still matching the concept expressed in the determinatives (qn and nxt are, in fact, virtual synonyms).83 Note that elsewhere in these inscriptions, nxt appears in the shorter writings  (below in both A/1 and B/1) and

(below in both A/1 and B/1) and  (A/3).

(A/3).

To be sure, yet another reading could alternatively be proposed: tn (< Tni), meaning “Distinguished/Honored (Youth).” This suggestion has the advantage of requiring hardly any emendation to the original text: the mutual position of the two signs would simply be inverted, nt in lieu of tn, and such accidental inversions can occur in these obelisks’ inscriptions. The verb Tni is not normally associated with the determinatives found here in our inscription, however, which is why I ultimately consider this interpretation unlikely.84

(2) <nb.ty>: An accidental omission in A, contra Jürgen von Beckerath, who considers the following iTi m sxm as still part of Domitian’s Horus name, thus implying that his Two Ladies name was completely omitted from the inscription.85

(3) iTi ˹m sxm˺: This phrase, “He Who Conquers through Might” (despite the damage, m sxm is clearly recognizable in the writing  ), is already found in the titulary of earlier sovereigns, both Ptolemaic (as in the Two Ladies name of Ptolemy I Soter and the Horus name of Ptolemy X Alexander) and Dynastic (as in the Golden Falcon name of Amenhotep II).86 In Roman times the preparation of the royal titulary of the ruling pharaoh would still have been the prerogative of members of the Egyptian priesthood.87 It is thus unsurprising that its authors would often take inspiration from—or even reproduce—earlier titularies, be they of Ptolemaic or even Dynastic date (see also note 4 to this side below).

), is already found in the titulary of earlier sovereigns, both Ptolemaic (as in the Two Ladies name of Ptolemy I Soter and the Horus name of Ptolemy X Alexander) and Dynastic (as in the Golden Falcon name of Amenhotep II).86 In Roman times the preparation of the royal titulary of the ruling pharaoh would still have been the prerogative of members of the Egyptian priesthood.87 It is thus unsurprising that its authors would often take inspiration from—or even reproduce—earlier titularies, be they of Ptolemaic or even Dynastic date (see also note 4 to this side below).

(4) wsr rnp.w(t): Though damaged in A, the phrase is preserved in B, with a fuller writing of wsr. The same Golden Falcon name is attested for Ramesses II (wsr rnp.wt aA nxt.w).88

Note that a clear crack affects this section of obelisk A on all its four inscribed sides. This was left virtually unmarked in Erman’s copy, no doubt due to an accidental omission, which also led him to erroneously state that obelisk A was broken into four, rather than the actual five, fragments.89 The same crack is instead clearly marked in Ungarelli’s earlier copy, though for only three out of the four sides, namely, A/2–4. This is the reason why his copy inaccurately renders wsr rnp.w(t) here in A/1 as if intact: surely this was not the case, as confirmed by Georg Zoëga’s earlier copy, the first one ever published of the Benevento inscriptions, in 1797.

(5) <nsw.t bi.ty>: Another accidental omission in A (but correctly present in B). Certainly no text was lost in the lacuna caused by the crack affecting the obelisk at this point,90 since the top curve of the cartouche is still preserved just above the crack itself, underneath the arm-with-stick determinative (as is partly visible in Erman’s drawing and, much more clearly, on the original).

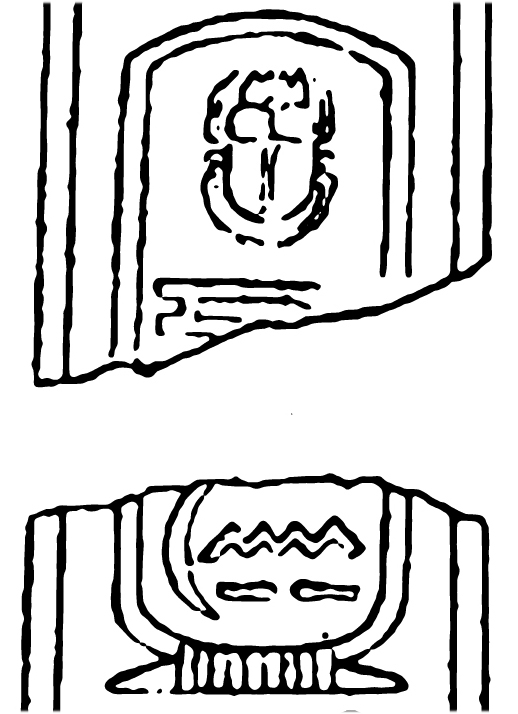

(6) K˹Y%˺R%: While obelisk A writes K%R%, obelisk B must have used the alternative spelling KY%R%, as can be reconstructed despite the lacuna. Indeed B shows the bottom end of three vertical strokes here, on the lower edge of the crack. In Erman’s facsimile only one such stroke is recorded, and there are none in Ungarelli’s earlier copy. All three are certainly original and not the result of later damage, however, for they were already marked in Zoëga’s copy. These three lines can only be the remainders of two reeds and a tall s, to the left of which would have stood the now missing final r of the preceding title AW&QR&[R], probably as a mouth-seen-sideways sign or even as a small standard mouth, thus:  or

or  (in context:

(in context:  or

or  ). Given the space available in the crack, which is quite limited, the signs in this sequence ys must have been carved rather small and compact (similar but even somewhat smaller than they are in the writings of the name Rwtl(y)ys in A/2–3 and B/4). Curiously, apart from omitting the traces of the three vertical strokes, Ungarelli’s copy shows this title as if still fully preserved in his time, in the writing

). Given the space available in the crack, which is quite limited, the signs in this sequence ys must have been carved rather small and compact (similar but even somewhat smaller than they are in the writings of the name Rwtl(y)ys in A/2–3 and B/4). Curiously, apart from omitting the traces of the three vertical strokes, Ungarelli’s copy shows this title as if still fully preserved in his time, in the writing  K%R%. Clearly this cannot have been the case, and Ungarelli must have restored this passage based on A’s version. This suspicion is confirmed by a number of other inaccuracies that affect his copy in this area; see, for example, the excessive width of k and the presence, above it, of the second r of AW&QR&R, which are both contradicted by the original.

K%R%. Clearly this cannot have been the case, and Ungarelli must have restored this passage based on A’s version. This suspicion is confirmed by a number of other inaccuracies that affect his copy in this area; see, for example, the excessive width of k and the presence, above it, of the second r of AW&QR&R, which are both contradicted by the original.

(7) nsw.t bi.ty: Obelisk A wrongly inserts this phrase before Domitian’s birth name, in lieu of the expected sA Ra, which is instead correctly given by B. Note also the modern damage to the t underneath the bee sign (absent from and likely postdating Erman’s copy).

(8) &˹M˺[&]IN%: Judging from the size of the lacuna in A, the lost sign was a flat one, namely  di/ti (as in A/3–4 and B/4). The child sign

di/ti (as in A/3–4 and B/4). The child sign  was clearly absent, as suggested both by the lacuna’s size, which is too small to accommodate it and, more importantly, by the fact that this is the sole occurrence in both obelisks in which n and s appear together in the cartouche as

was clearly absent, as suggested both by the lacuna’s size, which is too small to accommodate it and, more importantly, by the fact that this is the sole occurrence in both obelisks in which n and s appear together in the cartouche as  . In all other writings of Domitian’s name in these obelisks, only one or the other sign appears in this plain form, and it does so always in combination with the child sign, that is, as

. In all other writings of Domitian’s name in these obelisks, only one or the other sign appears in this plain form, and it does so always in combination with the child sign, that is, as  or

or  .

.

The hieroglyphic rendering of Domitian’s name as it appears in the Benevento obelisks is unparalleled.91 The first part, &mti, is unproblematic: it uses signs with values commonly attested in Ptolemaic and Roman times. As for the second half, the child sign is used interchangeably, with the phonetic value n (in A/4 and B/1–2) or s (in A/2–3, B/3 [with  above it lost in lacuna], and B/4), both of which are commonly attested for this sign.92 Finally, the moon crescent sign

above it lost in lacuna], and B/4), both of which are commonly attested for this sign.92 Finally, the moon crescent sign  has troubled a number of interpreters of this writing of Domitian’s name. Erman already considered it to stand for i,93 which is indeed the correct reading (through association with Greco-Roman writings of the name for the lunar god Thoth as i, for example,

has troubled a number of interpreters of this writing of Domitian’s name. Erman already considered it to stand for i,93 which is indeed the correct reading (through association with Greco-Roman writings of the name for the lunar god Thoth as i, for example,  ).94

).94

(9) xbi in(.w): Both the translations “he who collects” and “he who collected tribute” are possible. This phrase was misunderstood by the early editors of these obelisks; its correct reading was established only in later studies.95

(10) tA.wy: Written as two small squares in A,  , the reading is elucidated by the clearer writing in B,

, the reading is elucidated by the clearer writing in B,  . Iversen understands ns.ty “the two thrones,”96 but this reading is to be excluded, also on account of another occurrence of these square signs here in A/1, in the noun Xnw (written with the place name ITi-tA.wy: see note 13 to this side below).97

. Iversen understands ns.ty “the two thrones,”96 but this reading is to be excluded, also on account of another occurrence of these square signs here in A/1, in the noun Xnw (written with the place name ITi-tA.wy: see note 13 to this side below).97

As observed in previous scholarship,98 the mention of the Two Lands, a traditional name for Egypt in pharaonic inscriptions, can here be understood to designate not simply Egypt but also—from a Roman Weltanschauung—the entirety of the empire.

(11) m ntyy.w/nDy.w: Literally, “as subjects.” The standard spelling is nDy, but A shows a slightly different phonetic writing for it, ntyy, as well as an odd layout of the signs, with n placed at the end, rather than at the beginning, of the word (the word is much clearer in B, but problems with its writing clearly occurred here too, since the preposition follows the noun: literally, nDy.w m). This is a well-attested phrase, particularly in connection with xAs.wt, as in our obelisks.99

Traditionally designating the foreign, desert lands outside the Nile Valley—as opposed to tA.wy—in our case the subjugated xAs.wt can be reconceptualized as the territories beyond the Roman Empire’s borders. A number of interpreters understand this mention of gathering tribute from the empire and the enemy territories outside it not as a generic formula celebrating Domitian but as a specific reference to his return from his Dacian and Germanic campaigns in his eighth year, the same year when the obelisks were dedicated.100 As Frédéric Colin remarks, however, this must remain only a hypothesis, for this phrase concerning the gathering of tribute and the subjugation of foreign lands is a standard topos of pharaonic propaganda, which need not necessarily be tied to specific historical events.101

(12) iy.t: A problematic word, written consistently in both obelisks as  , which past interpreters have either left untranslated102 or generally understood as designating Domitian’s imperial palace in Rome, mainly on account of the house determinative

, which past interpreters have either left untranslated102 or generally understood as designating Domitian’s imperial palace in Rome, mainly on account of the house determinative  and of the use of the possessive “his.”103 In fact, a word iy.t is known from other sources to indicate not the royal residence but a sanctuary in the Egyptian city of Letopolis.104 This sanctuary included a cult of Osiris-Apis, and its priesthood might have enjoyed close connections with that of the Serapeum in Memphis.105 If this is the word intended in our obelisks, iy.t should therefore refer to a sanctuary here too, with the inscription perhaps alluding to a temple built or expanded by Domitian in Rome. It is tempting—but perhaps too far-fetched—to think of this sanctuary as the Iseum Campense, which in the ancient sources is associated with a Serapeum (it is simply labeled so, for example, in the Forma Urbis Romae) and which Domitian reconstructed following a fire in the year AD 80.106

and of the use of the possessive “his.”103 In fact, a word iy.t is known from other sources to indicate not the royal residence but a sanctuary in the Egyptian city of Letopolis.104 This sanctuary included a cult of Osiris-Apis, and its priesthood might have enjoyed close connections with that of the Serapeum in Memphis.105 If this is the word intended in our obelisks, iy.t should therefore refer to a sanctuary here too, with the inscription perhaps alluding to a temple built or expanded by Domitian in Rome. It is tempting—but perhaps too far-fetched—to think of this sanctuary as the Iseum Campense, which in the ancient sources is associated with a Serapeum (it is simply labeled so, for example, in the Forma Urbis Romae) and which Domitian reconstructed following a fire in the year AD 80.106

Alternatively, if iy.t does not refer to a temple, one may understand it as an aberrant writing of either: (a) the noun iw(y).t/iwA(y).t “house, city quarter” (also “sanctuary,” as the dwelling of a god), typically characterized by the house determinative both in hieroglyphs and in Demotic,107 which could fit here if understood as a reference to Rome’s imperial quarter, that is, Domitian’s palace; or (b) the noun iA.t “mound, place,” though the meaning would instead point, in this case, to a funerary context (hardly fitting here), and the use of the house determinative with this word would also be unexpected, hence making this second option highly unlikely.108

Finally, note that Pirelli translates this passage as “fino al ritorno nella città di Roma.”109 She must therefore understand iy.t as the infinitive of the verb “to come (back),” but such a translation does not account for the house determinative, ignores the possessive =f, and does not explain the following genitival preposition n.t. Thus it should be rejected.

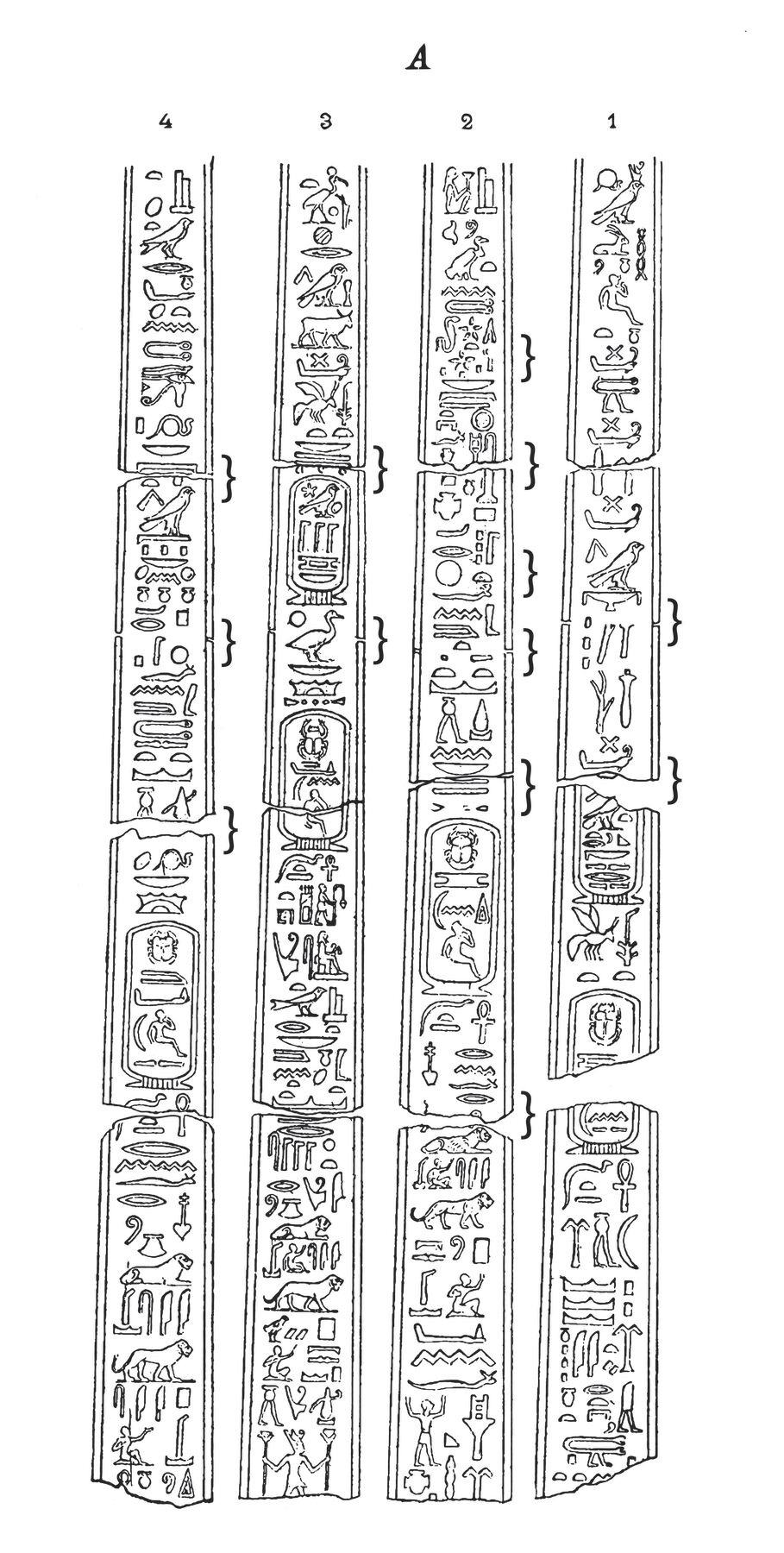

(13) Xnw: Taken sign by sign, the reading of this group should be ITi-tA.wy, with tA.wy written again with two small squares in A,  (see note 10 to this side above), and, in a clearer writing, with two scarab beetles in obelisk B,

(see note 10 to this side above), and, in a clearer writing, with two scarab beetles in obelisk B,  . ITi-tA.wy literally means “The Conqueror of the Two Lands”110 and was originally the name of the Middle Kingdom royal residence established by Amenemhat I (12th Dynasty, twentieth century BC), probably near el-Lisht.111 Its name became synonymous with capital city (Egyptian Xnw), so that, in later and, most typically, Greco-Roman times, it could aptly be used to designate any royal residence, as is the case here, where it specifically refers to Rome. As a consequence, the hieroglyphic group used to write ITi-tA.wy can itself be a sportive writing for the word Xnw112 and thus be translated simply as “royal residence, capital city.”113 Normally, when this sign group has such a value, its elements are encased by a wall, as in

. ITi-tA.wy literally means “The Conqueror of the Two Lands”110 and was originally the name of the Middle Kingdom royal residence established by Amenemhat I (12th Dynasty, twentieth century BC), probably near el-Lisht.111 Its name became synonymous with capital city (Egyptian Xnw), so that, in later and, most typically, Greco-Roman times, it could aptly be used to designate any royal residence, as is the case here, where it specifically refers to Rome. As a consequence, the hieroglyphic group used to write ITi-tA.wy can itself be a sportive writing for the word Xnw112 and thus be translated simply as “royal residence, capital city.”113 Normally, when this sign group has such a value, its elements are encased by a wall, as in  . Yet, even in the absence of a wall element around the signs, as in the case of our obelisks’ inscriptions, the reading Xnw and the translation “capital city” (rather than the specific toponym ITi-tA.wy) are not in doubt.114

. Yet, even in the absence of a wall element around the signs, as in the case of our obelisks’ inscriptions, the reading Xnw and the translation “capital city” (rather than the specific toponym ITi-tA.wy) are not in doubt.114

It is worth noting that the use of this hieroglyphic group in our obelisks also allows for a visual play linking Domitian and Rome, the emperor and his capital, under the shared concept of might. This is achieved by means of the hieroglyph  , iTi “to seize, to conquer,” which appears in a ring composition of sorts both in the emperor’s Two Ladies name at the start of this side’s inscription (iTi m sxm) and, though not to be read phonetically, in the designation of the capital city here at its end (Xnw < ITi-tA.wy).

, iTi “to seize, to conquer,” which appears in a ring composition of sorts both in the emperor’s Two Ladies name at the start of this side’s inscription (iTi m sxm) and, though not to be read phonetically, in the designation of the capital city here at its end (Xnw < ITi-tA.wy).

In theory, to think of all possibilities, one could alternatively here understand Xnw as an abridged writing of the preposition m-Xnw “in.” If so, the preceding n.t would not be a genitival preposition, but a writing of the relative converter nt(y). In this case, the whole phrase would translate somewhat differently, namely: “to his sanctuary(?), which is in Rome.”

(14) [!r]˹m˺: In A, only the very top part of an m in its  shape and two t’s originally associated with the foreign-land determinative (

shape and two t’s originally associated with the foreign-land determinative ( ) survive, with the former sign being barely discernible and absent from Ungarelli’s copy. The original form and arrangement of the signs, given the size of the lacuna, was possibly

) survive, with the former sign being barely discernible and absent from Ungarelli’s copy. The original form and arrangement of the signs, given the size of the lacuna, was possibly  . As is the case with Benevento’s name (see note 9 to side 2), that of Rome is also followed by the foreign-land determinative, since the Egyptian author of the inscription—irrespective of where he was actually based, in Italy or Egypt—conceptualized both cities as foreign, un-Egyptian places.

. As is the case with Benevento’s name (see note 9 to side 2), that of Rome is also followed by the foreign-land determinative, since the Egyptian author of the inscription—irrespective of where he was actually based, in Italy or Egypt—conceptualized both cities as foreign, un-Egyptian places.

Concerning the writing of the name of Rome in hieroglyphs, a recent study has remarked on the presence of initial h in the Benevento obelisks and other Roman hieroglyphic inscription as if an oddity.115 Far from it, this h is in fact a regular and integral element in any Egyptian transcription of Rome’s name, which is typically attested in either a shorter or a fuller writing (respectively, !rm, as in our obelisks, or !rmA and comparable spellings).116 Its presence is not intrusive but is surely derived from a precise transliteration into Egyptian of the name of Rome in Greek (which, of course, would have been the first language through which knowledge of Rome would have come to Egypt). Specifically, it is the way in which Egyptian must have noted the aspiration attached to the letter rho, which, when in the word-initial position, has a rough breathing, appearing as ῥ: indeed, the Greek name of Rome is Ῥώμη.

Note that in B the bottom right half of the inscription (the section containing the name of Rome), which was intact at the time of Erman, is now severely damaged.

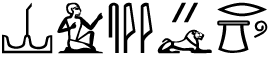

Side 2

Summary

Following a celebration of Isis, the text records the erection of the obelisks in honor of her and of the gods of Benevento by a private dedicator, Rutilius Lupus. A passage, the interpretation of which remains controversial (and which appears also in the texts of sides 3 and 4), potentially identifies the occasion for the obelisks’ dedication as the return of Domitian from his Dacian and Germanic campaigns. Good wishes, probably referring to the dedicator, conclude this side.

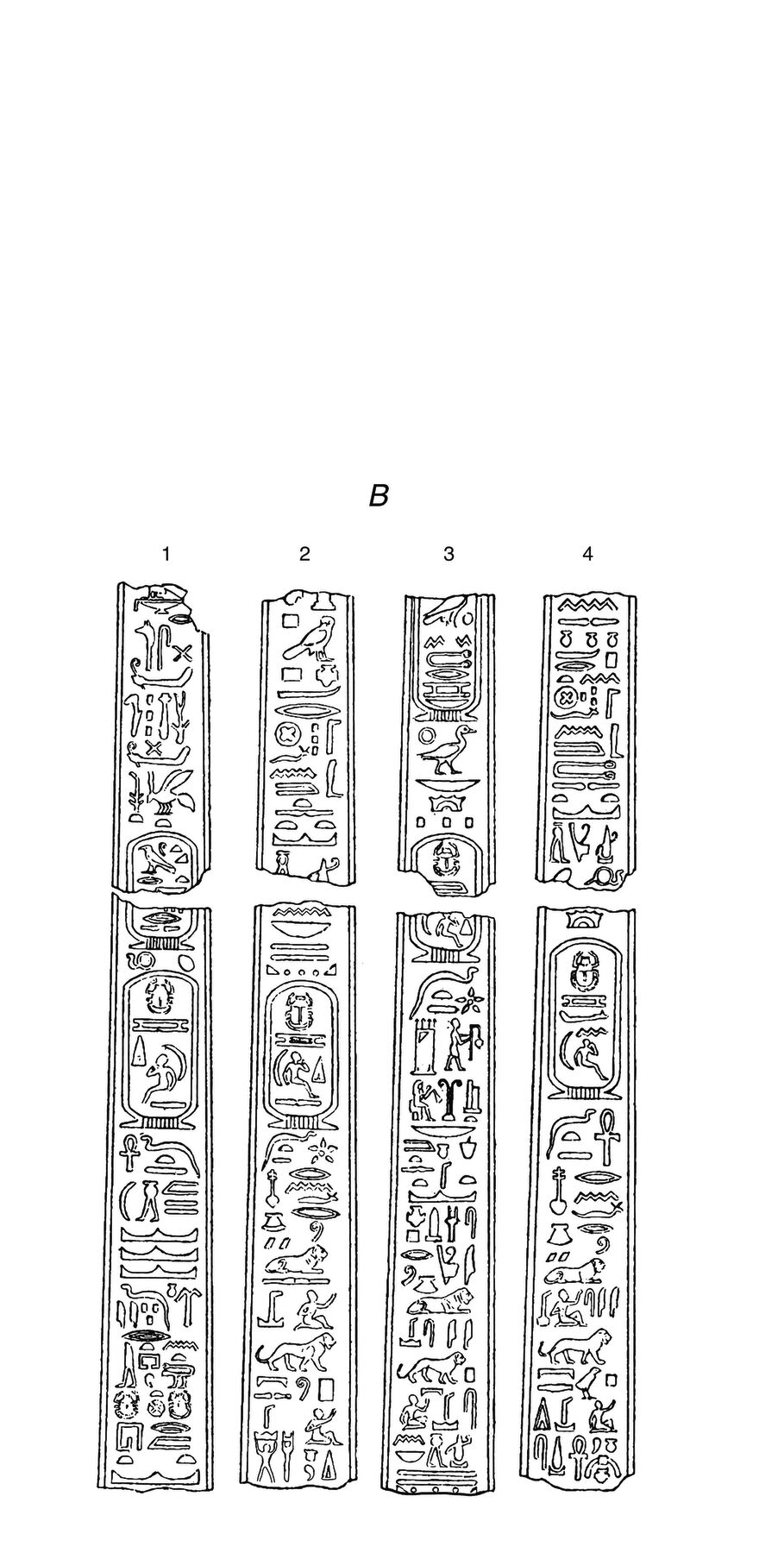

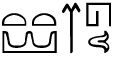

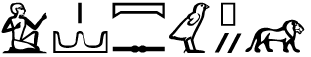

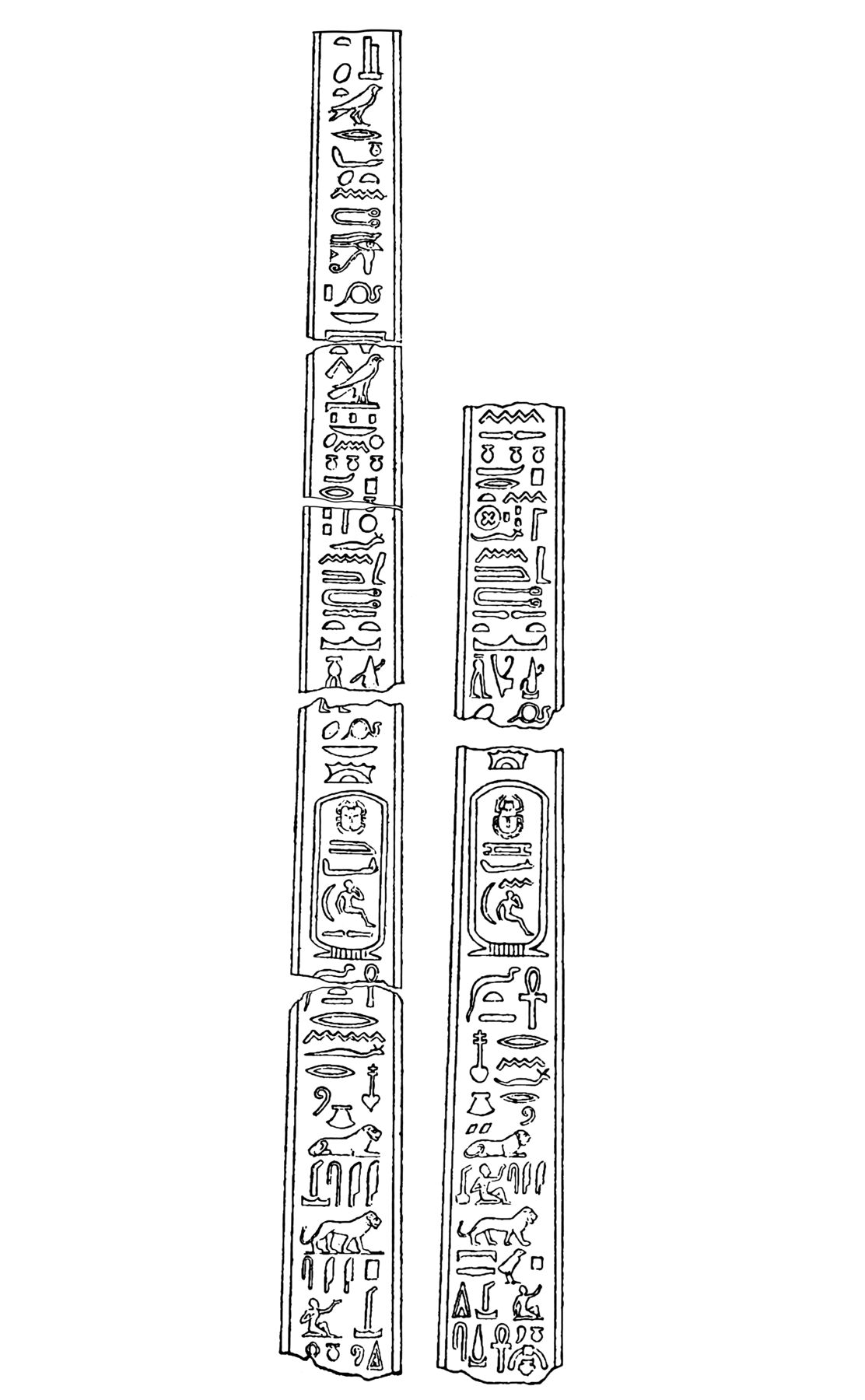

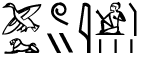

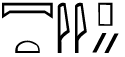

Figure 7.14

Figure 7.14 Figure 7.15

Figure 7.15 Figure 7.16

Figure 7.16 Figure 7.17

Figure 7.17| Obelisk A (Piazza Papiniano) | Obelisk B (Museo del Sannio) |

|---|---|

| ↓→ As(.t) wr(.t) mw.t nT(r) %pd.t HqA.t anx.w nb(.t) p(.t) tA dwA.t saHa=f n=˹s˺ txn n inr mAT Hna nTr.w niw.t=f Bnmts (w)DA ini n nb tA.wy &M&IN% anx D.t rn=f nfr R˹wt˺l˹y˺ys Lpws di n=f aHaw qAi m nDm-ib | ↓→ [. . .] ˹txn˺ m inr mAT Hna nTr.w niw(.t)=f Bnmts ˹wDA ini˺ n nb tA.wy &M&IN% anx D.t rn=f nfr Rwtlys Lpws di n=f aHaw qAi |

| Isis the Great, the God’s Mother, Sothis, Queen of the Stars, Lady of the Sky, the Earth, and the Netherworld: he erected an obelisk of granite stone to her and the gods of his city, Benevento, so that the return of the Lord of the Two Lands Domitian, ever-living, might be prosperous. His good name is Rutilius Lupus. May a long lifetime in joy be granted to him. | […] an obelisk of granite stone […] and the gods of his city, Benevento, so that the return of the Lord of the Two Lands Domitian, ever-living, might be prosperous. His good name is Rutilius Lupus. May a long lifetime be granted to him. |

Notes

(1) nT(r): Note the phonetic writing,  , which is found again in A/4 (and see also note 4 to side 3). As already pointed out by Colin, the word is used here in the singular, as normally expected in this common epithet of Isis referring to her son Horus as “the god.”117 A translation in the plural (“la mère des dieux”), given by Malaise and since repeated by various authors,118 is incorrect.

, which is found again in A/4 (and see also note 4 to side 3). As already pointed out by Colin, the word is used here in the singular, as normally expected in this common epithet of Isis referring to her son Horus as “the god.”117 A translation in the plural (“la mère des dieux”), given by Malaise and since repeated by various authors,118 is incorrect.

(2) %pd.t HqA.t: Based on its position between the two words, the feminine ending  t can be considered to be in zeugma, as applying to both. The HqA sign,

t can be considered to be in zeugma, as applying to both. The HqA sign,  , is reproduced as damaged in Erman’s copy but is in fact fully preserved.

, is reproduced as damaged in Erman’s copy but is in fact fully preserved.

(3) HqA.t anx.w: Or, perhaps, to be transliterated with another word for “star,” for example, HqA.t sbA.w? The logographic writing,  , leaves both options open, and while the star sign is used with the value anx in B/2–3, this is in the phrase anx D.t, in which the word’s meaning is a different one, “to live.” Svenja Nagel transliterates here nb.t sbA.w/sw.w, choosing sbA or, rather, the rendering of its contemporary pronunciation sw (compare Demotic sw and Coptic ⲥⲓⲟⲩ “star”);119 her nb.t in lieu of the expected HqA.t is certainly only an oversight, in that the reading of the crook sign is indisputable. Nonetheless, I believe the reading anx.w to be preferable, on account of parallels for this title of Isis/Isis-Sothis, in which the word is phonetically spelled out as such.120

, leaves both options open, and while the star sign is used with the value anx in B/2–3, this is in the phrase anx D.t, in which the word’s meaning is a different one, “to live.” Svenja Nagel transliterates here nb.t sbA.w/sw.w, choosing sbA or, rather, the rendering of its contemporary pronunciation sw (compare Demotic sw and Coptic ⲥⲓⲟⲩ “star”);119 her nb.t in lieu of the expected HqA.t is certainly only an oversight, in that the reading of the crook sign is indisputable. Nonetheless, I believe the reading anx.w to be preferable, on account of parallels for this title of Isis/Isis-Sothis, in which the word is phonetically spelled out as such.120

Several other interpreters have read this phrase quite differently, namely, as HqA.t nTr.w “Queen of the Gods.”121 This is, in theory, a possible reading, and such a title is indeed attested for Isis.122 The epithet “Queen of the Stars” applied to Isis in her identification with the star Sothis is not only more fitting, however, but is also confirmed by parallels.123 It should therefore be favored.

(4) nb(.t): It is unclear why Iversen oddly translates the male “Lord,” rather than “Lady,” since this epithet refers to Isis (same in his translation of A/4).124

Erman wonders if nb may in fact stand for nb(.w) and refer not to Isis but to the previous word (which he reads as nTr.w), thus understanding the whole as “Queen of the Gods, the Lords of the Sky, the Earth, and the Netherworld.”125 This, however, is surely not the case: the title still belongs to the list of epithets of Isis that opens the inscription on this side.

(5) n=˹s˺: The suffix pronoun, written with a small  , is marked as lost in Erman’s copy, but in fact largely survives, just on the edge of the lacuna.

, is marked as lost in Erman’s copy, but in fact largely survives, just on the edge of the lacuna.

(6) ˹txn˺: At the beginning of the surviving text in B, there is a damaged obelisk sign for txn and, to its left, the remainders of another sign (marked as undistinguished damage in Ungarelli’s copy), the nature of which is unclear. Its traces could match the shape of a granite bowl,  , perhaps used as an ad hoc determinative for the word txn “obelisk.” Note, however, that in A (as well as in B/3) txn has no determinative and, if a determinative were present after it, one would typically expect the plain stone sign,

, perhaps used as an ad hoc determinative for the word txn “obelisk.” Note, however, that in A (as well as in B/3) txn has no determinative and, if a determinative were present after it, one would typically expect the plain stone sign,  . Alternatively, the traces could perhaps belong to a nw pot sign: if so, this section of the text should be transcribed in a slightly different order than I have, as

. Alternatively, the traces could perhaps belong to a nw pot sign: if so, this section of the text should be transcribed in a slightly different order than I have, as  , and transliterated as ˹txn n˺ inr m mAT (with m being the genitival n, transformed through anticipatory assimilation to the following mAT). The translation (literally, “an obelisk of stone of granite”) would remain largely unaffected.

, and transliterated as ˹txn n˺ inr m mAT (with m being the genitival n, transformed through anticipatory assimilation to the following mAT). The translation (literally, “an obelisk of stone of granite”) would remain largely unaffected.

(7) n/m inr mAT: The first stone sign in this passage is a logogram for inr “stone,” while the second is a determinative for mAT “granite”;126 the signs are to be read, right to left, in this order:  (A; the granite vase and the second stone signs are inverted in the original) and

(A; the granite vase and the second stone signs are inverted in the original) and  (B; this is according to my proposed reading, but see an alternative interpretation in note 6 to this side). In A, the writing of the preposition m as n is a late feature (compare Demotic m > n); B uses instead the expected Middle Egyptian writing, m. Note also that, in B/3, we read

(B; this is according to my proposed reading, but see an alternative interpretation in note 6 to this side). In A, the writing of the preposition m as n is a late feature (compare Demotic m > n); B uses instead the expected Middle Egyptian writing, m. Note also that, in B/3, we read  txn mAT, with neither an intervening preposition nor the word inr, probably on account of the lack of space (alternatively—but less plausibly—one could read it as txn inr mAT, by positing an inversion of the last two signs, with the stone block for inr and the vase sign, with no determinative, for mAT). As already pointed out by Erman,127 Domitian’s Pamphili obelisk in Rome is also described in its own inscriptions as made of the same material: it is another

txn mAT, with neither an intervening preposition nor the word inr, probably on account of the lack of space (alternatively—but less plausibly—one could read it as txn inr mAT, by positing an inversion of the last two signs, with the stone block for inr and the vase sign, with no determinative, for mAT). As already pointed out by Erman,127 Domitian’s Pamphili obelisk in Rome is also described in its own inscriptions as made of the same material: it is another  txn m in(r) mAt “obelisk of granite stone.”128 Note also that, in his translation of the Benevento inscriptions, Erman freely renders the original text as “red granite,” since this is the stone of which the obelisks are made,129 and this mention of “red granite” is still repeated in modern studies that closely depend on his translation.130 Yet mAT does not indicate exclusively “red” granite, nor is such an adjective or explicit characterization of the stone’s color originally present in the inscriptions—neither here nor in B/3.

txn m in(r) mAt “obelisk of granite stone.”128 Note also that, in his translation of the Benevento inscriptions, Erman freely renders the original text as “red granite,” since this is the stone of which the obelisks are made,129 and this mention of “red granite” is still repeated in modern studies that closely depend on his translation.130 Yet mAT does not indicate exclusively “red” granite, nor is such an adjective or explicit characterization of the stone’s color originally present in the inscriptions—neither here nor in B/3.

(8) Hna nTr.w niw.t=f: In A, note the inverted arrangement of the signs, with nTr.w coming before Hna, with another inversion affecting the niw.t sign and its t ending.

Mention of other, unspecified deities sharing with Isis the dedication of the obelisks (and of the Beneventan Iseum itself) appears again in A/4 and B/4 (both have “the gods of his [sc., the dedicator’s] city, Benevento,” as here on side 2) as well as in A/3 (recording “her [sc., Isis’s] Ennead”).131 The identity of these theoi synnaoi of Isis in Benevento remains unknown, though it is possible—or even likely—that they would have included other gods of Egyptian origin.132

(9) Bnmts: Despite the crack in A and the damage recorded in Erman’s copy, the final s  is, in fact, fully preserved. The writing of the city’s name in Egyptian hieroglyphs is predictably a hapax, found only on these monuments. It is written consistently Bnmts (or the phonetic equivalent BnmTs) in both obelisks, except for A/3, where it appears in a fuller writing, as Bnmnts (this side is also notable for its more diversified choice of hieroglyphs, with A/3 having

is, in fact, fully preserved. The writing of the city’s name in Egyptian hieroglyphs is predictably a hapax, found only on these monuments. It is written consistently Bnmts (or the phonetic equivalent BnmTs) in both obelisks, except for A/3, where it appears in a fuller writing, as Bnmnts (this side is also notable for its more diversified choice of hieroglyphs, with A/3 having  for s, and B/3 using

for s, and B/3 using  for b).133 In theory, a transliteration Bnbts/BnbTs/Bnbnts might also be possible, as the interchange of m(n) and b is attested in texts from the time.134

for b).133 In theory, a transliteration Bnbts/BnbTs/Bnbnts might also be possible, as the interchange of m(n) and b is attested in texts from the time.134

The fact that the Egyptian rendering of the city’s name ends with the letter s points to an original Greek draft, rather than Latin, on the basis of which the Middle Egyptian text was composed.135 Indeed, while the city is known in Latin only as Beneventum,136 in Greek it is attested both as Βενεουεντόν/Βενεουέντον and as Βενεβεντός/Βενεουεντός, with final sigma.137 The latter writing is clearly at the origin of the Egyptian rendition (compare especially the orthography Βενεβεντός with the full hieroglyphic writing of A/3, Bnmnts/Bnbnts). It should also be noted that the existence of a Greek and of a Latin draft are not mutually exclusive. Guidelines for the inscriptions may first have been prepared in Latin following the instructions of the Beneventan dedicator, then translated into Greek as an intermediary passage, and thence used as a draft outline for the final Middle Egyptian version. It should come as no surprise that an Egyptian priest (the only person able to compose a hieroglyphic Middle Egyptian text in the first century AD) would have been more familiar with Greek, the lingua franca of the Roman East, than with Latin.138 Note also how the name of Benevento is consistently followed by a foreign-land determinative  (in association with a throw-stick sign, which also indicates foreignness, in B/3:

(in association with a throw-stick sign, which also indicates foreignness, in B/3:  ), as was the case with the name of Rome on side 1 (see note 14 to that side).

), as was the case with the name of Rome on side 1 (see note 14 to that side).

(10) wDA ini: This phrase, which appears in the middle of the inscription on sides 2 and 4 and at the end of side 3 in both obelisks, constitutes a major problem in the interpretation of the text. Two radically different translations have been suggested to date. The first was proposed by Erman,139 who understands the phrase as meaning “for the well-being and return” (of the emperor), with the two verbs used as nominalized infinitives, and sees in it a rendering of the Latin expression pro salute et reditu: “he erected an obelisk … for the well-being and return of the Lord of the Two Lands.” The obelisks would thus have been erected on the occasion of Domitian’s return to Rome after a military expedition. This interpretation has the advantage of connecting the date of the obelisks’ dedication (AD 88/89, based on the text of side 3) with that of Domitian’s Dacian and Germanic campaigns—that is, respectively, the war against Decebalus and the revolt of Saturninus—and his following return to Rome in AD 89 (see note 11 to side 1 above).

At least two serious problems affect this translation, however. First, the verb ini does not mean “to come (back)” but “to bring (back).” Erman’s proposed solution to this issue is far from convincing. He considers ini to be a very literal translation from Greek κομίζειν, active voice “to bring” / κομίζεσθαι, passive voice “to return,”140 but the lexicon used throughout these inscriptions is overall the expected and correct Middle Egyptian vocabulary, and such an unidiomatic use of the Egyptian language at a crucial passage would be most surprising. Second, in none of its six occurrences is the phrase wDA ini introduced by a preposition (the expected equivalent of Latin pro). This consistent absence of a preposition is all the more conspicuous when compared with the otherwise regular presence of the genitival preposition n after this phrase (in virtually all cases, wDA ini n nb tA.wy “the wDA ini of the Lord of the Two Lands” / wDA ini n sA Ra “the wDA ini of the Son of Re,” with the sole exception of A/4), especially when considering that the genitival n is otherwise one of the most commonly omitted prepositions in Egyptian texts as a whole. For his part, Erman remarks that the omission of a preposition before wDA ini is no big issue. In his support, he points out that the datival preposition n (the one which, in his opinion, he would expect before wDA ini) is generally omitted in the Benevento inscriptions.141 Close scrutiny proves him wrong, however, showing that in both obelisks the datival preposition is correctly employed and written eight times, and only once (in B/3, before As.t) is it omitted. Erman’s interpretation and his proposed solutions to the issues that it raises thus fall short of convincing.

A second and entirely different interpretation of the phrase was offered by Iversen.142 His premise is the same as Erman’s, for Iversen also thinks that wDA ini must be the rendering of a Latin expression. In his case, however, he considers it an Egyptian neologism translating the Latin title legatus (Augusti). To justify his proposal, he understands wDA not as the verb “to be well, prosperous,” but as the verb “to proceed, to travel,” notwithstanding the lack of the walking-legs determinative  that one would typically expect after this verb (though such an omission might perhaps be justified on account of the walking legs already present within the following sign, ini). He thus translates wDA ini as “the one who travels and brings (back)” > “the legate” (or even, still according to Iversen, “he who goes forth and returns,” supposing that ini may here be an—unparalleled—writing of an “to return”). The chief advantage of his solution is that wDA ini would thus fit perfectly in the syntax of the text, being another reference to the grammatical subject of the sentence, the monument’s dedicator: “he erected an obelisk …, (namely) the legate of the Lord of the Two Lands …, whose good name is …” Further, prosopographical evidence would also seem to invite such a translation, as we know of the existence of an individual of Beneventan origin, Marcus Rutilius Lupus (for more on the dedicator’s name, see notes 14 and 15 to this side below), who indeed bore the title of legatus Augusti.143

that one would typically expect after this verb (though such an omission might perhaps be justified on account of the walking legs already present within the following sign, ini). He thus translates wDA ini as “the one who travels and brings (back)” > “the legate” (or even, still according to Iversen, “he who goes forth and returns,” supposing that ini may here be an—unparalleled—writing of an “to return”). The chief advantage of his solution is that wDA ini would thus fit perfectly in the syntax of the text, being another reference to the grammatical subject of the sentence, the monument’s dedicator: “he erected an obelisk …, (namely) the legate of the Lord of the Two Lands …, whose good name is …” Further, prosopographical evidence would also seem to invite such a translation, as we know of the existence of an individual of Beneventan origin, Marcus Rutilius Lupus (for more on the dedicator’s name, see notes 14 and 15 to this side below), who indeed bore the title of legatus Augusti.143

Even with Iversen’s proposal, however, there are serious issues. One is the unexpected presence of a unique neologism in a text that otherwise uses standard Middle Egyptian lexicon (except, of course, for rendering Roman personal and geographic names). The other is the lack of any determinative following this phrase to help the reader (including the ancient reader, given the supposed neologism!) understand its meaning. After wDA ini, one would at least have expected a seated-man determinative,  , ideally even combined with a foreign-land determinative,

, ideally even combined with a foreign-land determinative,  or

or  (as is the case with the personal name of the dedicator—see notes 14 and 15 to this side).

(as is the case with the personal name of the dedicator—see notes 14 and 15 to this side).