5. The Kellis Mammisi: A Painted Chapel from the Final Centuries of the Ancient Egyptian Religion

- Olaf E. Kaper

Professor of Egyptology, Institute for Area Studies, Leiden University

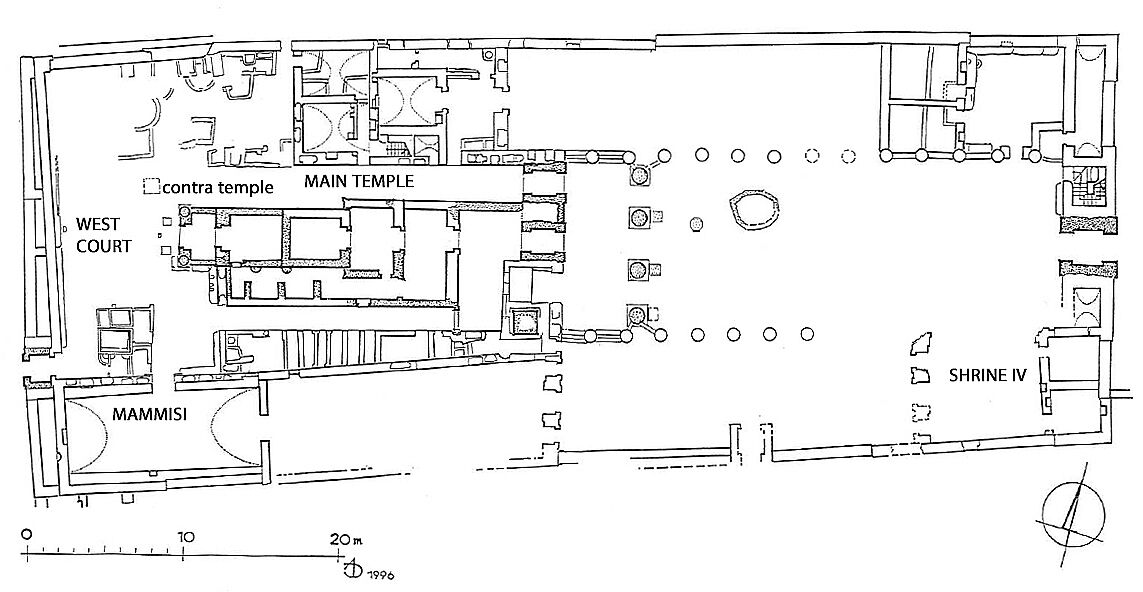

The mammisi of Kellis is one of the major archaeological finds in Egypt from the past forty years (fig. 5.1). (A mammisi is a birth house in the form of a subsidiary chapel belonging to a larger temple.) Its significance lies in its wall paintings, which offer a radical new perspective on the religion of Roman Egypt. It overturns the established notion that the temples in the south of Egypt followed traditional patterns and that true innovation of religious ideas took place in major cult centers but not in the countryside. This article presents some of the most important paintings in this shrine for the first time.

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Kellis is a village situated in the center of Dakhla Oasis, one of the large oases of the Western Desert, which was administered in combination with the neighboring Kharga Oasis.1 The village was abandoned before the end of the fourth century AD, and it has been under excavation since 1986 under the direction of Colin Hope. Its remains include a large temple enclosure, houses, workshops, three remarkably large villas with wall paintings,2 a bathhouse, three churches, several cemeteries, and possibly a nymphaeum.3

The village temple was dedicated to a relatively new Egyptian god: Tutu, designated in Greek as Totoes or Tithoes. This god first emerged as a local deity of the town of Sais in the 26th Dynasty,4 after which his cult spread throughout the country. Despite the god’s wide popularity, the Kellis temple is the only known example that was dedicated primarily to Tutu. It is worth speculating as to why Tutu did not feature more prominently in the Egyptian religious landscape. It is not because he was merely a minor god, in the manner of the god Bes, who did not receive a temple cult anywhere in the country until late Roman times.5 Tutu, in contrast, did receive a cult in many temples as an associated deity, even when he was not the primary focus of the cult. Examples are the temples at Esna and Koptos.6 There are several priests of Tutu known from inscriptions, also outside of Kellis,7 and the temple calendar at Esna records two festival dates for Tutu.8 Perhaps the reason why the Kellis temple remained exceptional is to be sought in the date of its foundation in the early Roman period, at which time very few new temples were built in Egypt.9 The increasing popularity of Tutu was elsewhere incorporated into existing cults, and there were not many occasions when a new temple could be dedicated to the god. There may well have been other temples dedicated primarily to Tutu, but at this moment the Kellis temple is the only one known.

Several images of the god were found carved on stelae and depicted on the walls of the Kellis temple. Tutu is often depicted in Roman Egypt as a striding sphinx with a cobra as a tail, but on the temple walls he usually appears in fully human form.10 The god was in control of fate, and that is why his image could be combined with that of the Greek goddess Nemesis.11 He provided divine protection against illness and other misfortunes, which explains his popular appeal. His consort in Kellis was called Tapsais. She is not known from other sites, because she was probably a local woman who became a goddess after death.12 Like Tutu, she was in control of fate, and like Isis, she was depicted wearing a queen’s crown.13

The temple stopped functioning in the course of the fourth century AD,14 and the building was robbed of its stone subsequently, at an unknown date. Only a few blocks with relief decoration remained in situ. From these it is clear that building works at the Kellis temple started in the first century AD; the earliest inscriptional evidence dates to the time of Nero (r. AD 54–68).15 A fragmentary cartouche from the entrance gateway dates perhaps to Hadrian (r. AD 117–38), and other work was carried out under Antoninus Pius (r. AD 138–61) and Pertinax (r. AD 193).16 Finding Pertinax here is remarkable, because there are no other monuments in Egypt on which his name appears in hieroglyphs. Pertinax ruled for only three months in AD 193, and the relief therefore shows how essential the role of the pharaoh was still considered to be at this time. In this remote region at the border of the Roman Empire, knowing the identity of the emperor was still vital for the proper form of decoration on the walls of a village temple. Nevertheless, in Dakhla and Kharga the priests deviated from the practices in the Nile Valley, because they consistently reversed the order of the names of the emperor in the two cartouches.17 This remarkable show of independence may be explained by the local attachment to rules of decorum set under the last Ptolemies.18 The temple decoration in the oases was thus provided with a reference to the Hellenistic kings, which must have enhanced the religious significance of the temple decoration with a historical dimension in accordance with local tradition.

The Kellis temple is one of the smallest temples known in Egypt, with only a few tiny rooms. Its small size may be explained by a scarcity of local funds in this village, which could not procure large amounts of stone from the local quarries and pay for the necessary stonemasons. The financing of local temple buildings in the villages of Roman Egypt probably did not involve the central government at all, despite the practice of inscribing the name of the emperor on its walls.19 At the same time, this small temple was set within a large enclosure that contained a wide array of buildings associated with the temple cult. Not much of this enclosure and its various subdivisions has been excavated, so its purpose remains subject to speculation.

Next to the stone temple, on a parallel axis, stands the mammisi. This building consists of an inner room measuring 4.8 meters in width and 12 meters in depth, with a slightly larger forecourt.20 This makes the mammisi much larger than any room of the stone temple, but it was built of mud brick, which made its construction much less costly. In contrast to the stone temple, the mammisi is preserved in its entirety, even though the vaulted roof collapsed in antiquity. The inner room of the building was excavated between 1991 and 2004, and the fragments of its former painted plaster decoration were retrieved. The conservation and reconstruction of the paintings continued between 2004 and 2011, after which work at the site had to be interrupted.21

The walls of the mammisi still stand up to 3.5 meters in its southwest corner (fig. 5.2). Its decoration consists of paintings on a thin layer of plaster, which is still attached to the walls. The entire vaulted ceiling, which contains most of the figurative decoration, had become fragmented, and only small parts remained attached to clusters of bricks from the collapsed vault. In order to conserve and reconstruct the decoration, a system was devised by the conservators Michelle Berry and Laurence Blondaux by which the thin layer of plaster could be removed from its brick support and united with the loose fragments that had been found in its surroundings.22 Reconstructed scenes could be glued together and fixed on a wooden support, which allows handling and will ultimately make it possible to display the scenes.23 The illustrations in the present essay show some of the results to date.

The building is remarkable, and two aspects of the decoration make it unique. First, it is completely painted using two different systems of representation (styles). A dado of classical paneling is painted below, surrounded by vines and with a series of different birds depicted within each panel, which also includes a (mostly vandalized) Medusa head in its center.24 Its dating is probably early second century AD, based on the style and colors of the paintings,25 which resemble those of the richer houses at Kellis from the early second century.26 The Medusa heads are a known feature of classical panel decoration and are also present in Roman temples in Italy of the first century.27

Greek influence was important in the oases already from an early time, and it is one of the distinguishing features of the local culture, where it is more dominant than in the Nile Valley.28 The clearest indication in archaeology is the widespread adoption of Greek ceramic forms in the oasis during the Ptolemaic period.29 The adoption of Roman-style wall paintings should not be a surprise, therefore, even though their appearance in an Egyptian temple is totally unexpected.

Above the classical paneling are four registers of Egyptian-style images and hieroglyphs. The reconstruction of the vault is now largely completed, and nearly every detail can be reconstructed from fragments (fig. 5.3). This twofold scheme is unconventional in an Egyptian temple, and it requires an explanation. I have argued elsewhere that there was a greater freedom from decorum in the oases,30 which may have fostered the creation of this original shrine, but I am now convinced of a more specific motivation for its conception.

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3A cultic niche situated in the back wall of the mammisi resembles the lararium niches, or aediculae, found in Roman houses in Egypt as well as in Italy,31 even though no examples of such niches are as yet known from the houses of Kellis.32 The niche in the mammisi had modeled pilasters on either side and a plaster conch shell within its arched upper part. This domestic element is striking and unparalleled within an Egyptian temple context.33 Beneath the niche was an apron, a console with a projecting platform on which divine statues and other objects could be placed. This element had originally been attached to the wall using wooden pegs, but it became detached during the collapse of the vaulted roof, and its remnants were found on the floor underneath the niche. The apron was reconstructed from fragments, and its decoration is striking (fig. 5.4). It is known to have been symmetrical in shape and decoration, even though the left end of the apron is lost. The decoration shows a large central calyx of an acanthus leaf on a white background, with floral extensions on either side combined with the figure of a winged naked youth (Eros) holding bunches of grapes. The presence of these putti has a parallel on the apron of a domestic aedicula found in a late Roman house in Amheida, Dakhla Oasis.34 The parallel has two seated Eros figures facing each other, and their presence in a private house indicates that the Eros figures were not specifically selected for the mammisi but belong to the architectural form and general significance of the aedicula. Only the Eros on the right has been preserved on the Kellis apron. The grapes in his hands echo the vines surrounding the dado panels on the same wall. On either side of the central acanthus leaf, open lotus flowers are depicted, an Egyptian element that probably refers to the statues to be placed on top of the platform. In accordance with the cultic function of the mammisi, it is likely that statues in Egyptian style of both Tutu and his mother, Neith, were present, placed above the two lotus flowers depicted on the apron.35

Figure 5.4

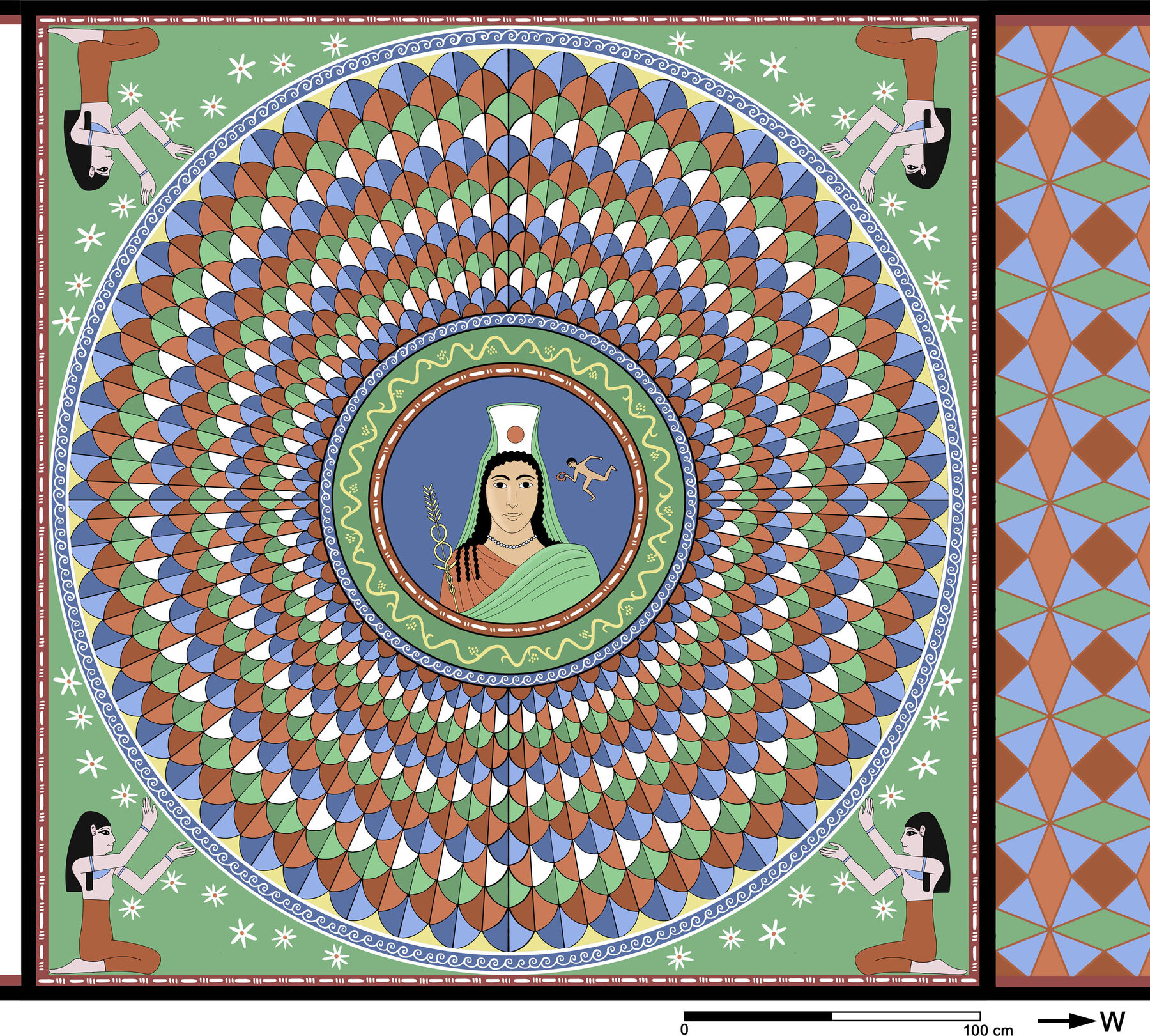

Figure 5.4The combination of lotus flowers with classical-style decoration is also found at the bottom of the walls of the mammisi, where a series of broad, elongated panels were painted, each separated by lotus flowers. Evidently the painters of these elements were familiar with Egyptian iconography. This familiarity is even more apparent from the paintings on the highest part of the vault of the mammisi, a wide band that spanned the length of the room and that was decorated largely with paintings in the Roman tradition. The three large patterns on this band are familiar from the classical repertoire as known from the walls of houses and public buildings,36 but the central element is more complicated. This pattern was constructed around a large circular element of radiating scales or feathers, which is more familiar from mosaic floors.37 At the heart of this circular feature was probably a painted bust of Isis-Demeter, of which only a part remains. The circle is surrounded in the four corners of the pattern by four seated goddesses set amid a sprinkle of white flowers on a green ground that visually suggests a sky with stars (fig. 5.5). One of these corner figures has been reconstructed from fragments (fig. 5.6).38 The appearance and system of representation (style) of the goddesses is purely Egyptian, with tight red dresses and long black hair, but the circular part of the painting is in the Roman system of representation, even when it includes Isis as its central image.

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.5 Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6The most remarkable aspect of this painting is the way that the ancient artist(s) took two familiar designs from two different artistic traditions and merged them into a new, powerful image. The juxtaposition of the two styles has added a new layer of meaning to the circular mosaic pattern by turning it into an image of the sky held up by the four supports of heaven. The latter are well known from circular images of the zodiac in Egypt, such as the one from Dendera now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris,39 and the ceilings of two painted tombs in Qarat el-Muzawwaqa, in Dakhla Oasis.40 One of the latter, in the tomb of Petubastis, has the goddesses in the same posture as in the Kellis painting and set against a background of stars, but the circular zodiac they are supporting is rendered according to the Egyptian system of representation.41

The Kellis painting demonstrates a high level of artistic freedom and an originality of design that is unparalleled in Egyptian temples. The combination of two systems of representation, the Egyptian and the Hellenistic or Roman, is familiar from tomb decoration in Roman Egypt,42 in which the religious content of the tomb or an item of tomb equipment, such as a shroud or a coffin, was made according to Egyptian conventions, whereas the individual who was the focal point of the tomb’s decoration was rendered in the more contemporary Hellenistic or Roman style. In this context, I employ the term style in a technical sense, as a system of representation in which the Egyptian artist worked according to a strict canon of proportions and with frontal, or “aspective,” images.43 In this respect the Egyptian artists differed from those of other cultures, and it was a difference that was consciously applied on funerary items and tomb walls in the Roman period. Only in the Kellis mammisi were the two styles equally divided over the walls and ceiling of a shrine.

The integration of the two systems of representation in a single painting, as on the Kellis chapel ceiling, may indicate that the same painters were versed in two different styles, especially since there are also other locations in the mammisi where the styles are found juxtaposed in a minor way. Unfortunately there is no way to be certain about this. We do not know anything about the persons responsible for the design of the mammisi paintings or about the painters themselves. In general we do not know much about the organization of the work of decorating temple walls. Each temple was different, and designing the layout and contents of each wall could involve much intricate planning, in ways that we are only beginning to understand.44

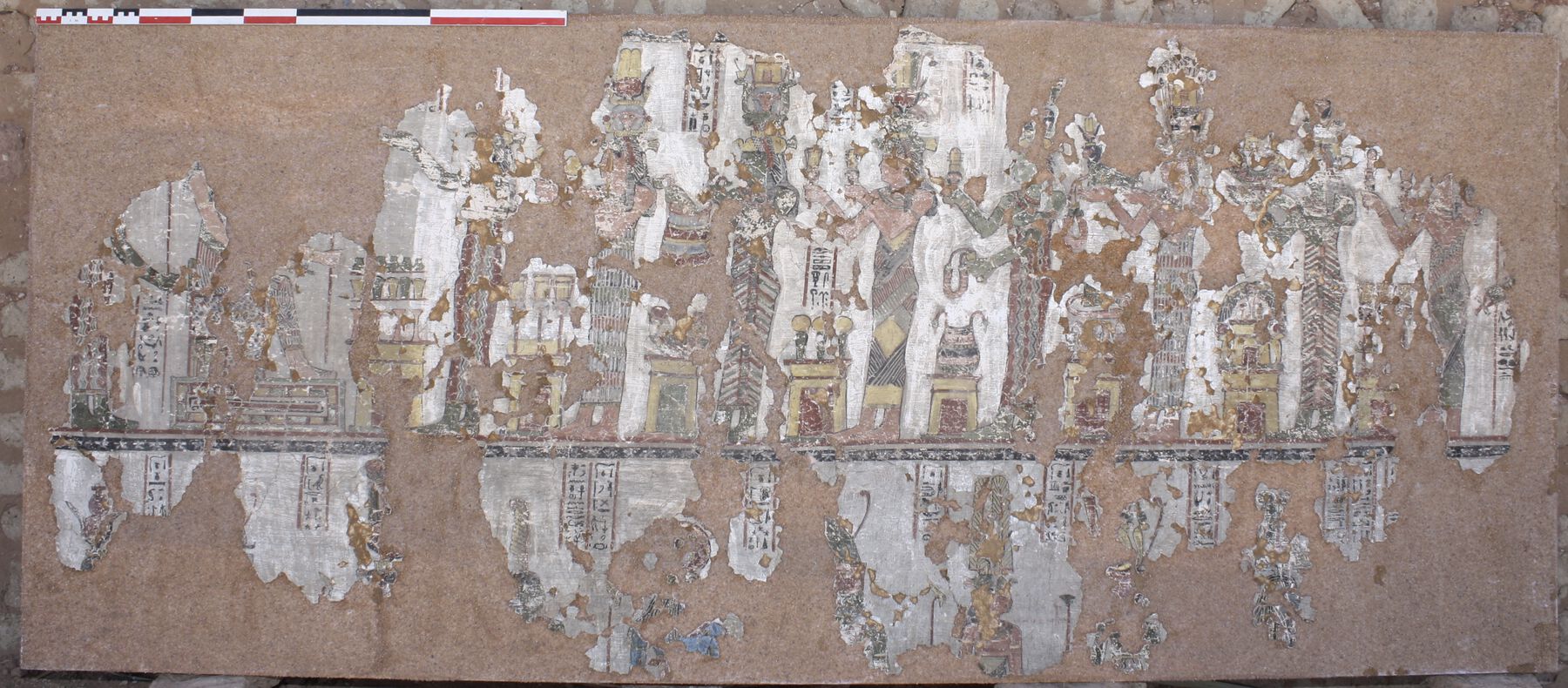

The Egyptian-style paintings of the mammisi focus on religious themes with only little attention to cultic or historical information. The majority of scenes refer to the cyclical rejuvenation of the gods through depictions of the subdivisions of time. The scenes include divine personifications of the years, the twelve months of the year, the thirty days of the month, the twelve hours of the day, and those of the night.45 Other scenes relate to the birth of the god Tutu, with images of the gods Ptah and Khnum seated at potter’s wheels,46 and of the Seven Hathors and Meskhenet goddesses.47 The scene of the Seven Hathors has been reconstructed from fragments (fig. 5.7), and a part of it is shown separately in detail here in order to demonstrate the high quality of the Egyptian-style paintings (fig. 5.8).48 Each figure was rendered with the use of each of the seven colors available to the painters in this style: yellow, red, blue, green, pink, black, and white. Each of the Hathors wears a different elaborate crown, and they hold objects in their hands as offerings to Tapsais, consisting of mirrors, floral collars, sistra, and menats. The same objects are also shown on top of small tables set in front of each goddess. The amount of detail and the expert way of drawing each image are remarkable, and it places the decoration of this mammisi on a par with the best relief work in the temples in the Nile Valley, notably that of Dendera from the reigns of Nero (r. AD 54–68) and Trajan (r. AD 98–117).49

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7The second unique aspect of the decoration of the mammisi is the way in which the role of the pharaoh is minimized within the decorative program. In total, there were more than four hundred gods depicted inside the mammisi, the name and titles of each designated in the accompanying hieroglyphic legends. Remarkably and in another divergence from regular practice, the gods are shown interacting among themselves, and there is no king represented serving them or rendering them homage. Only a single representation of a nameless king appears at the entrance to the shrine, on the inner face of the south doorjamb, a generic image of a king consecrating food offerings to the gods inside the mammisi. This is the only occurrence of a representation of the conventional role of the pharaoh, interacting with the gods on behalf of humankind.

The Kellis mammisi has suppressed the role of the king, and instead various minor gods play his part in the decorative program, presenting offerings to the major gods. At the same time, two scenes contain groups of priests performing offering rituals in front of the local deities. On the north and south walls of the shrine, twenty-seven and thirty-seven priests, respectively, are shown bringing cultic items to the gods of the temple: Tutu, Neith, and Tapsais.50 The first group of priests from the southern series is shown performing the daily ritual for Tutu, opening the shrine and bringing incense and libations (fig. 5.9). One of them is pouring oil on the floor from a situla, which is a ritual familiar from the archaeological remains of the Dakhla temples.51

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.9One factor that has to play a role in this exceptional shift of emphasis away from the human king can be found in the particular emphasis placed on the royal aspects of Tutu in the mammisi. There are many references to kingship in the god’s titles and iconography. Tutu’s name may be preceded by the title King of Upper and Lower Egypt or by the title King of the Gods, which he shares with Amun-Re.52 In his iconography, Tutu often wears the Double Crown, and he may be depicted subjugating the enemies of Egypt in the form of the Nine Bows.53 The emphasis on the royal traits of the god is a standard theological feature of the mammisi in general.54

It is not surprising that the king has been replaced by minor gods at Kellis, because mammisis always placed an emphasis on divine interaction in the scenes depicting the divine birth and its associated mythology.55 It would certainly be a mistake to conclude that the omission of the emperor’s name was intended as some kind of subversive political statement. We need only recall that the stone temple of Kellis mentions Pertinax among its cartouches. It is fair to say that the Kellis priests were highly loyal to the imperial authorities.

The real significance of the Kellis mammisi is that it shows a long-overdue modernization of the content of Egyptian temple decoration, which better reflects current practices and ideas. The role of the pharaoh had already diminished under the Ptolemies, but in Roman times the head of state lived not in Egypt but in Rome, and he took no active part in Egyptian religion and its cults.56 As a consequence, the gods themselves took on more of the aspects of kingship. Already before the arrival of Alexander the Great, the gods could be shown wearing royal garments and with their names written in cartouches,57 but this tendency became more pronounced in Roman times.

The omission of the pharaoh and his replacement by representations of priests is exactly what can be observed in the temples of Isis and Serapis built outside Egypt. These temples, such as the one in Pompeii, had taken the step of suppressing the role of the pharaoh earlier in the Roman period.58 Moreover, the temples to Egyptian gods outside Egypt included images of priests in their depictions of ritual activities. At the same time, the gods had taken on a distinct royal role, such as Isis in her role as Isis Regina.59 The Kellis mammisi adopted some of these new developments seen in the temples of Isis outside Egypt, combining Egyptian and foreign concepts of a temple. This was a big step, involving a rethinking of tradition with a revolutionary intent. We can appreciate the logic of the Kellis mammisi design because it reflects a new world in which there were no longer active pharaohs.

Just like the temples outside Egypt, those in the oases had more freedom to experiment. Experimentation is apparent also from the way the names of the Roman emperors were written, in the reverse order from the rest of Egypt. The Kellis mammisi upended age-old traditions, reflecting the essence of Egyptian religion in these changing times. The early second century AD was still a time of temple building and artistic investment in religious institutions, but in the course of the century a decline would set in. If the indigenous religion had continued to thrive, it is likely that comparable temple decoration would have appeared also in the Nile Valley. As it was, Egyptian religion became gradually more marginalized, and such a daring step could no longer be taken by the priests of a religion that was under severe pressure. Political and economic measures taken by the Roman state had impoverished the temples by removing their land and closely monitoring their assets.60 As a result, the economic crisis of the third century AD had an enormous impact on the temples, which could, as a consequence, no longer be maintained. Some rare temple-building projects in the Nile Valley, such as that at Esna, were continued in accordance with tradition, even as late as the reign of Decius (r. AD 249–51), but the priests and artists were no longer capable of innovative and creative designs.61 The Kellis mammisi was a brave attempt at innovation of the ancient religion, but the times proved to be unfavorable for the continuation of these ideas.

I am most grateful to the Getty Research Institute for the fellowship I received in 2017, which allowed me to develop some of the ideas discussed in this paper.

Notes

On the Southern Oasis, see . ↩︎

; ; . ↩︎

On Kellis, see the references in . On the nymphaeum, see G. E. Bowen in , 29–33. ↩︎

, 139, 264 [R–41]. ↩︎

On the various forms of Bes, see . There is no evidence for a temple cult for Bes, and also the evidence found in Bahariya Oasis, as reported in Hawass (, 168–73) is not conclusive. Only in late Roman times was Bes venerated at Abydos (, 169–79; , 120–29; ), and in Antinoupolis the god was assimilated to the divinized Antinous (, 2921). ↩︎

, 129–39 ↩︎

, 147. ↩︎

, 152, 235. ↩︎

. ↩︎

On Tutu’s iconography in general, see , 33–52; on the Kellis images specifically, see . ↩︎

On Nemesis in Egypt, see . ↩︎

On this phenomenon in general, see . ↩︎

; , 107–10. ↩︎

Priests of Tutu are attested in the papyri into the AD 330s; , 148–50; , 11–13. ↩︎

, 49–51. ↩︎

, 28–31. The Pertinax block is shown in , 90, fig. 133; , 143, 162, fig. 4. ↩︎

, 143. ↩︎

, 724–25. ↩︎

On private involvement in temple building in name of the Roman emperor, see , 93–104. ↩︎

On the architecture of the temple and the mammisi, see . ↩︎

Funding for the conservation effort since 2004, directed by the present writer, was provided mainly by the Mellon Foundation through a Distinguished Achievement Award to R. S. Bagnall. One season was funded by an excavation grant of the Egypt Exploration Society. ↩︎

The conservation of the painted plaster was initiated by Michelle Berry, and the system was developed further by Laurence Blondaux, who worked for fourteen seasons on the material; described in ; ; . ↩︎

The choice for wooden panels is explained in , 53–55. ↩︎

, 385; , 248–50. The paintings in classical style are being studied by Helen Whitehouse, who will participate in the publication of the mammisi. ↩︎

This dating was initially proposed in , 221–22, and confirmed in , 117. On the identification of the pigments used in the shrine, see . ↩︎

. Medusa heads are also found in the paneling of a large Roman villa in Kellis: H. Whitehouse in , 319–20; , 248–49. ↩︎

Moormann (, 68), describes the sanctuary of Bona Dea at Ostia, from the first quarter of the first century AD; in its cella is a black dado with paneling in which Medusa heads are one of the motifs. ↩︎

, 729–30. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 181–201; , 723–25, 729–30. ↩︎

As in the houses of Karanis: , 47–48, plates 72–74. For examples of aediculae outside Egypt, see , 75–81; , 30–33. ↩︎

A good parallel is found in the house tomb M13/SS in Tuna el-Gebel: , plate 43.2. Another parallel, with a tympanon, is found in Marina el-Alamein: , 57–58, fig. 5; , 52–53, fig. 5–6; , 68–69, fig. 5. ↩︎

A niche in the rear wall is known from several temple sanctuaries, but these always have the architectural form of an Egyptian naos shrine. Examples are the temple of Qasr Zayan (, 59, fig. 86), the temple of Isis at Tebtynis (, 43–51, 142, photo 47), the contra temple at Medinet Madi (, 161–63, 166), and the northern temple of Taffeh (, 95, fig. 101, 97, fig. 104). ↩︎

, 365. ↩︎

On the symbolism of the god emerging from the lotus, see . This theme is central to the theology of the mammisi; see . ↩︎

As confirmed for the painted decoration of temples in the classical world by Moormann (, 206): “As in private dwellings, figural elements were decorative and did not necessarily serve to emphasize the religious atmosphere. . . . Wall decorations in temples are akin to those in houses and public buildings.” ↩︎

See , 120–22; , 1018–20. ↩︎

The restoration of this piece is illustrated in , 7. ↩︎

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités égyptiennes, D 38 (E 13482), https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010028871; . On the supports of heaven, see . ↩︎

, plates 36, 38–44. ↩︎

, plates 36, 42b. ↩︎

, 211. ↩︎

With , 8–9. On aspective, see , xvi–xvii; ; , 49. ↩︎

The potential levels of complexity are well illustrated by the inner sanctuary of the Dendera temple, as studied in . A papyrus from Tanis is the only preserved document that contains rules and templates for creating temple decoration: ; , 103. ↩︎

, 217–23; . ↩︎

, 215–51. ↩︎

On the Seven Hathors, see , 44–49, 64–92; on the Meskhenet goddesses, see , 63–92. On the significance of the scene in the Kellis mammisi, see . ↩︎

The restoration of this panel is illustrated in , 10–21; on the use of color in this scene, see , 26. ↩︎

On the quality of these reliefs, see , 80, 86. ↩︎

, 87–137. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 59; , 319–20. ↩︎

, 59–60; , 314–15. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 5. ↩︎

, 14–46. ↩︎

, 37–39. ↩︎

, 93; , 105–11, 115–18. ↩︎

, 1178. ↩︎

, 27–30. ↩︎

The Esna temple was finished only under Decius, but Sauneron (, 43–44) remarks on the marked deterioration of skill and inspiration that is apparent already during the second century AD and progressively after that. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Bagnall and Tallet 2019

- Bagnall, Roger S., and Gaëlle Tallet. 2019. “The Great Oasis: An Administrative Entity from Pharaonic Times to Roman Times.” In The Great Oasis of Egypt: The Kharga and Dakhla Oases in Antiquity, edited by Roger S. Bagnall and Gaëlle Tallet, 83–104. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bagnall and Worp 2002

- Bagnall, Roger S., and Klaas A. Worp. 2002. “An Inscribed Pedestal from the Temple of Tutu.” In Dakhleh Oasis Project: Preliminary Reports on the 1994–1995 to 1998–1999 Field Seasons, edited by Colin A. Hope and Gillian E. Bowen, 49–51. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Baines 1974

- Baines, John. 1974. “Translator’s Introduction.” In Principles of Egyptian Art, by Heinrich Schäfer, edited by Emma Brunner-Traut and translated and edited by John Baines, xi–xix. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Berry 2002

- Berry, Michelle. 2002. “The Study of Pigments from Shrine I at Ismant el-Kharab.” In Dakhleh Oasis Project: Preliminary Reports on the 1994–1995 to 1998–1999 Field Seasons, edited by Colin A. Hope and Gillian E. Bowen, 53–60. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Bettles 2020

- Bettles, Elizabeth. 2020. “Pink in the Kellis Mammisi and Kalabsha Temple: Solar Theology and Divine Gender in Roman Period Cultic Monuments.” In Dust, Demons and Pots: Studies in Honour of Colin A. Hope, edited by Ashten R. Warfe et al., 25–38. Leuven: Peeters.

- Bettles and Kaper 2011

- Bettles, Elizabeth, and Olaf E. Kaper. 2011. “The Divine Potters of Kellis.” In Under the Potter’s Tree: Studies on Ancient Egypt Presented to Janine Bourriau on the Occasion of Her 70th Birthday, edited by David Aston et al., 215–51. Leuven: Peeters.

- Blondaux 2002

- Blondaux, Laurence. 2002. “Conservation of Archaeological Wall Paintings in the Temple of Tutu.” In Dakhleh Oasis Project: Preliminary Reports on the 1994–1995 to 1998–1999 Field Seasons, edited by Colin A. Hope and Gillian E. Bowen, 61–63. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Blondaux 2008

- Blondaux, Laurence. 2008. “Conservation at Ismant el-Kharab: Examples of Wall Painting in Shrine 1.” In The Oasis Papers 2: Proceedings of the Second International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by Marcia F. Wiseman, 151–52. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Blondaux 2020

- Blondaux, Laurence. 2020. “Conserving Wall Paintings in Archaeological Fields: A Case Study from Kellis, Dakhleh Oasis.” In Dust, Demons and Pots: Studies in Honour of Colin A. Hope, edited by Ashten R. Warfe et al., 49–56. Leuven: Peeters.

- Bowen et al. 2007

- Bowen, Gillian E., et al. 2007. “Brief Report on the 2007 Excavations at Ismant el-Kharab.” Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 18:21–52.

- Bresciani and Giammarusti 2015

- Bresciani, Edda, and Antonio Giammarusti. 2015. I templi di Medinet Madi nel Fayum. Pisa: Plus, Pisa University Press.

- Brunner-Traut 1974

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1974. “Epilogue: Aspective.” In Principles of Egyptian Art, by Heinrich Schäfer, edited by Emma Brunner-Traut and translated and edited by John Baines, 421–46. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Castiglione 1961

- Castiglione, László. 1961. “Dualité du style dans l’art sépulcral égyptien à l’époque romaine.” Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 9:209–30.

- Cauville 1997

- Cauville, Sylvie. 1997. Le zodiaque d’Osiris. Leuven: Peeters.

- Clarke 2003

- Clarke, John R. 2003. Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 315. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dobrowolski 2002

- Dobrowolski, Jarosław. 2002. “Remarks on the Construction Stages of the Main Temple and Shrines I–II.” In Dakhleh Oasis Project: Preliminary Reports on the 1994–1995 to 1998–1999 Field Seasons, edited by Colin A. Hope and Gillian E. Bowen, 121–28. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Effland 2014

- Effland, Andreas. 2014. “‘You Will Open Up the Ways in the Underworld of the God’: Aspects of Roman and Late Antique Abydos.” In Egypt in the First Millennium AD: Perspectives from New Fieldwork, edited by E. O’Connell, 193–205. Leuven: Peeters.

- Effland and Effland 2013

- Effland, Andreas, and Ute Effland. 2013. Abydos: Tor zur ägyptischen Unterwelt. Mainz-Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Frankfurter 1998

- Frankfurter, David. 1998. Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gabra et al. 1941

- Gabra, Sami, et al. 1941. Rapport sur les fouilles d’Hermoupolis Ouest (Touna el-Gebel). Cairo: Université Fouad Ier.

- Gallazzi and Hadji-Minaglou 2000

- Gallazzi, Claudio, and Gisèle Hadji-Minaglou. 2000. Tebtynis I: La reprise des fouilles et le quartier de la chapelle d’Isis-Thermoutis. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Gill 2016

- Gill, James C. R. 2016. Dakhleh Oasis and the Western Desert of Egypt under the Ptolemies. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Guimier-Sorbets 1998

- Guimier-Sorbets, Anne-Marie. 1998. “Le pavement du triclinium à la méduse dans une maison d’époque impériale à Alexandrie.” In Alexandrina 1, edited by Jean-Yves Empereur, 115–39. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Hartwig 2015

- Hartwig, Melinda K., ed. 2015. A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hawass 2000

- Hawass, Zahi. 2000. Valley of the Golden Mummies. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Hölbl 2000

- Hölbl, Günther. 2000. Altägypten im Römischen Reich: Der römische Pharao und seine Tempel. Vol. 1, Römische Politik und altägyptische Ideologie von Augustus bis Diocletian: Tempelbau in Oberägypten. Mainz: Zabern.

- Hölbl 2005

- Hölbl, Günther. 2005. Altägypten im Römischen Reich: Der römische Pharao und seine Tempel. Vol. 3, Heiligtümer und religiöses Leben in den ägyptischen Wüsten und Oasen. Mainz: Zabern.

- Hope 2004

- Hope, Colin A. 2004. “Ostraka and the Archaeology of Ismant el-Kharab.” In Greek Ostraka from Kellis, edited by Klaas A. Worp, 5–27. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Hope 2009

- Hope, Colin A. 2009. “Ismant el-Kharab: An Elite Roman Period Residence.” Egyptian Archaeology 34 (Spring): 20–24.

- Hope 2013

- Hope, Colin A. 2013. “Kellis.” In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, edited by Roger S. Bagnall et al., 3726–28. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hope 2015

- Hope, Colin A. 2015. “The Roman-Period Houses of Kellis in Egypt’s Dakhleh Oasis.” In Housing and Habitat in the Ancient Mediterranean: Cultural and Environmental Responses, edited by Angelo Andrea Di Castro, Colin A. Hope, and Bruce E. Parr, 199–229. Leuven: Peeters.

- Hope and Whitehouse 2006

- Hope, Colin A., and Helen Whitehouse. 2006. “A Painted Residence at Ismant el-Kharab (Kellis) in the Dakhleh Oasis.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 19 (2): 313–28.

- Husselman 1979

- Husselman, Elinor M. 1979. Karanis Excavations of the University of Michigan in Egypt 1928–1935: Topography and Architecture; A Summary of the Reports of the Director, Enoch E. Peterson. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kákosy 1995

- Kákosy, László. 1995. “Probleme der Religion im römerzeitlichen Ägypten.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt (ANRW) / Rise and Decline of the Roman World: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der aktuellen Forschung. Pt. 2, Principat. Vol. 18.5, Religion: Heidentum (Die religiösen Verhältnisse in den Provinzen), edited by Wolfgang Haase, 2894–3049. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kaper 1997

- Kaper, Olaf E. 1997. “Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhleh: Studies in the Indigenous Cults of an Egyptian Oasis.” PhD diss., University of Groningen.

- Kaper 1998

- Kaper, Olaf E. 1998. “Temple Building in the Egyptian Deserts during the Roman Period.” In Life on the Fringe: Living in the Southern Egyptian Deserts during the Roman and Early-Byzantine Periods. Proceedings of a Colloquium Held on the Occasion of the 25th Anniversary of the Netherlands Institute for Archaeology and Arabic Studies in Cairo, 9–12 December 1996, edited by Olaf E. Kaper, 139–58. Leiden: Research School CNWS.

- Kaper 2002

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2002. “Pharaonic-Style Decoration in the Mammisi at Ismant el-Kharab: New Insights after the 1996–1997 Field Season.” In Dakhleh Oasis Project: Preliminary Reports of the 1994–1995 to 1998–1999 Field Seasons, edited by Colin A. Hope and Gillian E. Bowen, 217–23. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Kaper 2003a

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2003a. The Egyptian God Tutu: A Study of the Sphinx-God and Master of Demons with a Corpus of Monuments. Leuven: Peeters.

- Kaper 2003b

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2003b. “The God Tutu at Kellis: On Two Stelae Found at Ismant el-Kharab in 2000.” In The Oasis Papers 3: Proceedings of the Third International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by Gillian E. Bowen and Colin A. Hope, 311–21. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Kaper 2009

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2009. “Restoring Wall Paintings of the Temple of Tutu.” Egyptian Archaeology 35 (Autumn): 3–7.

- Kaper 2010

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2010. “Galba’s Cartouches at Ain Birbiyeh.” In Tradition and Transformation: Egypt under Roman Rule, edited by Katja Lembke, Martina Minas-Nerpel, and Stefan Pfeiffer, 181–201. Leiden: Brill.

- Kaper 2012a

- Kaper, Olaf E., ed. 2012a. Colours of the Oasis: Artists and the Archaeology of Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt. Leiden: privately printed.

- Kaper 2012b

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2012b. “Departing from Protocol: Emperor Names in the Temples of Dakhleh Oasis.” In Auf den Spuren des Sobek: Festschrift für Horst Beinlich zum 28. Dezember 2012, edited by Jochen Hallof, 137–62. Dettelbach: Röll.

- Kaper 2012c

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2012c. “The Western Oases.” In The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt, edited by Christina Riggs, 717–35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kaper 2019

- Kaper, Olaf E. 2019. “The Egyptian Royal Costume in the Late Period.” In Egyptian Royal Ideology and Kingship under Periods of Foreign Rulers: Case Studies from the First Millennium BC, edited by Julia Budka, 31–39. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Kaper forthcoming

- Kaper, Olaf E. Forthcoming. “The Mammisi of Tutu in Kellis: Towards a New Definition of Birth Houses.” In Mammisis of Egypt: Proceedings of the 1st International Colloquium Cairo, Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, March 27–28, 2019, edited by Ali Abdelhalim Ali and Dagmar Budde. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Kaper and Worp 1995

- Kaper, Olaf E., and Klaas A. Worp. 1995. “A Bronze Representing Tapsais of Kellis.” Revue d’Égyptologie 46:107–18.

- Kockelmann 2011

- Kockelmann, Holger. 2011. “Mammisi (Birth House).” In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, edited by Willeke Wendrich. Los Angeles: University of California. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026wfgr.

- Kockelmann and Pfeiffer 2009

- Kockelmann, Holger, and Stefan Pfeiffer. 2009. “Betrachtungen zur Dedikation von Tempeln und Tempelteilen in ptolemäischer und römischer Zeit.” In “. . . vor dem Papyrus sind alle gleich!”: Papyrologische Beiträge zu Ehren von Bärbel Kramer (P. Kramer), edited by Raimar Eberhard et al., 93–104. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kurth 2016

- Kurth, Dieter. 2016. Wo Götter, Menschen und Tote lebten: Eine Studie zum Weltbild der alten Ägypter. Hützel: Backe.

- Leitz 2001

- Leitz, Christian. 2001. Die Aussenwand des Sanktuars in Dendara: Untersuchungen zur Dekorationssystematik. Mainz: Zabern.

- Lichocka 2004

- Lichocka, Barbara. 2004. Nemesis en Égypte romaine. Mainz: Zabern.

- Lieven 2010

- Lieven, Alexandra von. 2010. “Deified Humans.” In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, edited by Jacco Dieleman and Willeke Wendrich. Los Angeles: University of California. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0025k5hz.

- McFadden 2014

- McFadden, Susanna. 2014. “Art on the Edge: The Late Roman Wall Paintings of Amheida, Egypt.” In Antike Malerei zwischen Lokalstil und Zeitstil: Textband, edited by Norbert Zimmermann, 359–70, plates 125–27. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Medeksza 1999

- Medeksza, Stanisław. 1999. “Marina El-Alamein Conservation Work, 1998.” In Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean X: Reports 1998, 51–62. Warsaw: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw.

- Medeksza 2000

- Medeksza, Stanisław. 2000. “Marina El-Alamein Conservation Work, 1999.” In Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean XI: Reports 1999, 47–57. Warsaw: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw.

- Medeksza 2001

- Medeksza, Stanisław. 2001. “Marina El-Alamein—Conservation Work 2000.” In Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean XII: Reports 2000, 63–75. Warsaw: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw.

- Moormann 2011

- Moormann, Eric M. 2011. Divine Interiors: Mural Paintings in Greek and Roman Sanctuaries. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Moormann 2016

- Moormann, Eric M. 2016. “Il tempio di Iside a Pompei e la sua scoperta.” In Il Nilo a Pompei: Visioni d’Egitto nel mondo romano, edited by Federico Poole, 105–20. Turin: Panini.

- Nagel 2019

- Nagel, Svenja. 2019. Isis im Römischen Reich. Vol. 2, Adaption(en) des Kultes im Westen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Osing et al. 1982

- Osing, Jürgen, et al., eds. 1982. Denkmäler der Oase Dachla aus dem Nachlass von Ahmed Fakhry. Mainz: Zabern.

- Quack 2014

- Quack, Joachim Friedrich. 2014. “Die theoretische Normierung der Soubassement-Dekoration: Erste Ergebnisse der Arbeit an der karbonisierten Handschrift von Tanis.” In Altägyptische Enzyklopädien: Die Soubassements in den Tempeln der griechisch-römischen Zeit. Vol. 1, Soubassementstudien 1, edited by Alexa Rickert and Bettina Ventker, 17–27. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Quack 2016

- Quack, Joachim Friedrich. 2016. “Wie normativ ist das Buch vom Tempel, und wann und wo ist es so?” In 10. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Ägyptische Tempel zwischen Normierung und Individualität, edited by Martina Ullmann, 99–109. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Riggs 2005

- Riggs, Christina. 2005. The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rochholz 2002

- Rochholz, Matthias. 2002. Schöpfung, Feindvernichtung, Regeneration: Untersuchung zum Symbolgehalt der machtgeladenen Zahl 7 im alten Ägypten. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Ross 2002

- Ross, Andrew. 2002. “Identifying the Oil Used in the Rituals in the Temple of Tutu.” In Dakhleh Oasis Project: Preliminary Reports on the 1994–1995 to 1998–1999 Field Seasons, edited by Colin A. Hope and Gillian E. Bowen, 263–67. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Sauneron 1959

- Sauneron, Serge. 1959. Esna I: Quatre campagnes à Esna. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Schlögl 1977

- Schlögl, Hermann. 1977. Der Sonnengott auf der Blüte: Eine ägyptische Kosmogonie des Neuen Reiches. Basel: Éditions de Belles-Lettres.

- Schneider 1979

- Schneider, Hans D. 1979. Taffeh: Rond de wederopbouw van een Nubische tempel. The Hague: Staatsuitgeverij.

- Sofroniew 2015

- Sofroniew, Alexandra. 2015. Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome. Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publications.

- Spieser 2011

- Spieser, Cathie. 2011. “Meskhenet et les sept Hathors en Égypte ancienne.” In Des Fata aux fées: Regards croisés de l’Antiquité à nos jours, edited by Martine Hennard Dutheil de la Rochère and Véronique Dasen, 63–92. Lausanne: Université de Lausanne.

- Volokhine 2017

- Volokhine, Youri. 2017. “Du côté des ‘Bès’ infernaux.” In Entre dieux et hommes: Anges, démons et autres figures intermédiaires, edited by Thomas Römer et al., 60–87. Fribourg: Academic Press; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Whitehouse 2010

- Whitehouse, Helen. 2010. “Mosaics and Painting in Graeco-Roman Egypt.” In Companion to Ancient Egypt, edited by Alan B. Lloyd, 2:1008–31. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Whitehouse 2012

- Whitehouse, Helen. 2012. “Vine and Acanthus: Decorative Themes in the Wall-Paintings of Kellis.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by Roger S. Bagnall, Paola Davoli, and Colin A. Hope, 381–90. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Whitehouse 2015

- Whitehouse, Helen. 2015. “A House, but Not Exactly a Home? The Painted Residence at Kellis Revisited.” In Housing and Habitat in the Ancient Mediterranean: Cultural and Environmental Responses, edited by Angelo Andrea Di Castro, Colin A. Hope, and Bruce E. Parr, 243–54. Leuven: Peeters.