4. The Creation of New “Cultural Codes”: The Ptolemaic Queens and Their Syncretic Processes with Isis, Hathor, and Aphrodite

- Martina Minas-Nerpel

Professor of Egyptology, University of Trier

The fourth century BC was a period of widespread transformation, marked by the transition from the ancient Near Eastern empires to the Hellenistic kingdoms, in which Egypt played a central role. Through the conquests of Alexander the Great, the known world became more intensively interconnected than ever before. Egypt was already a millennia-old civilization with a rich intellectual, artistic, and cultural tradition, and the foundation of Alexandria (331 BC) in the context of the rise of the Hellenistic kingdoms provided a new way in which the land by the Nile was centralized, one that invited even greater cross-cultural interaction. For the Ptolemies (305/4–30 BC), the Greco-Macedonian rulers of Hellenistic Egypt, the use of the past was crucial to constructing an identity for their multicultural empire. To achieve this, they used different identities in different circumstances, connecting themselves to existing Egyptian traditions, modifying them, or creating new ones.

On the basis of two case studies, this contribution highlights the cross-cultural exchange that influenced Ptolemaic royal ideology, in particular the Ptolemaic royal women, resulting in new modes of (self-)presentation. These new modes also had a large impact on the goddesses with whom the queens were associated, first and foremost Isis, Hathor, and Aphrodite. I concentrate on two highly exceptional queens: Arsinoe II (ca. 316–270 BC), with whom the Ptolemaic ruler cult began in the Egyptian temples, and Cleopatra VII (69–30 BC), with whom the Ptolemaic dynasty perished after almost three centuries.

These two case studies illuminate the creation of intricate patterns of Ptolemaic queenship connected to the divine world. Arsinoe II set the example in many respects, which led to the Ptolemaic queens’ increased status and prestige. This was expressed in various ways, visually and textually. For the purpose of this contribution, I concentrate in Arsinoe’s case mainly on textual evidence, which spans from references in the classical literature to epithets in Egyptian temple inscriptions. Once created, these epithets were used throughout the Ptolemaic period, including in the reign of Cleopatra VII, not only for the queens but also for the goddess Isis, emphasizing their close association.

Motivated by different political circumstances, Cleopatra VII developed additional modes of presentation, analyzed in the second case study mainly through architectural evidence, reaching from Alexandria to Meroe, in Nubia. The last Ptolemaic queen connected herself to the centuries-old Ptolemaic patterns but was not afraid to break with existing traditions if necessary, for instance, by not being laid to rest in the Sema, where Alexander and the previous Ptolemies were buried. By having her own separate tomb built, she created a new role for herself, emphasizing the beginning of a new era. According to Appian and Cassius Dio, Caesar had a gold statue of the Ptolemaic queen placed in the temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome, right next to the statue of the goddess herself.1 Thus Caesar not only associated Cleopatra with the ancestral mother of his own family but also publicly acknowledged her divinity in Rome. The Julian Venus Genetrix could be assimilated to Isis-Aphrodite and Isis Regina.2 Cleopatra VII, as the mother of Caesar’s only biological son, Caesarion, probably intended to style herself as the genetrix of a new dynasty, which drew on Julian and Ptolemaic origins.3 With Marc Antony and his children, she also tried ambitiously to secure the once dominant Ptolemaic position in the East, but she failed in the end.

Ideological Framework

Egyptian kingship, a demonstration of the power of the creator god, was assumed by a mortal ruler who needed divine legitimation. According to the Myth of the Divine Birth,4 the pharaoh was the bodily offspring of the gods and thus their deputy. Such myths were mobilized politically and used to establish and reinforce the king’s and the dynasty’s claim to the throne.5 The numerous women surrounding the king, whose role was defined by their relationship to him, were intended to support him, while he relied on them, notably for the transmission of the office from father to son. The king’s mother was the protector of this transition, a role filled in the divine world by Isis, who conceived Horus, the son of Osiris. A feminine element is necessary in all creative and generative acts, ensuring renewal and continuity.6

The king’s wife was considered to be a manifestation of Hathor, the female prototype of creation, a goddess who received specific attention in the Ptolemaic period. For example, in the temple of Hathor at Dendera the goddess can be depicted with the wꜣs-scepter ( ), which is normally attributed to male gods, rather than the wꜣḏ-scepter (

), which is normally attributed to male gods, rather than the wꜣḏ-scepter ( ), which is usually held by goddesses. Together with epithets that describe her as the creator god (such as nb.t r ḏr, “Lady of All”), this scepter confirms Hathor’s androgynous characteristics.7 As the queen was the manifestation of Hathor on earth, this concept also applied to her, further defining her role within the dynasty as a creator.

), which is usually held by goddesses. Together with epithets that describe her as the creator god (such as nb.t r ḏr, “Lady of All”), this scepter confirms Hathor’s androgynous characteristics.7 As the queen was the manifestation of Hathor on earth, this concept also applied to her, further defining her role within the dynasty as a creator.

In theory, female power did not compete with kingship, which was predominantly male, but women with political power were not isolated cases, and some rulers had a female identity, such as Hatshepsut in the 18th Dynasty. On the one hand, Hellenistic royal women generally gained prestige and power by giving birth to a child, especially the heir. On the other hand, knowledge acquired through their role as priestesses also set these royal women apart and marked them as active participants in the cult, as is described below for Arsinoe II. The more symbolic disposition of prestige is rather difficult to measure but can be translated into political power. The Ptolemaic queens, especially Arsinoe II and Cleopatra VII, and their advisers and supporters must have been very much aware of the possibilities that were created by establishing new roles and modes of presentation for royal women, including the interactions with the divine world. As Lana Troy has described, the analogy between kingship and the androgyny of the creator enables the female monarch to manifest herself in the masculine role: “The female Horus provides a shift in emphasis in the character of the king but remains consistent with the basic worldview of the Egyptian.”8 The Egyptian priests of the Ptolemaic period played not only with the modes of iconographic expression in temple reliefs, stelae, and statues9 but also—or especially—with hieroglyphs and designations that were applied to both queens and goddesses. This is illuminated below by specific epithets, which were applied to the Ptolemaic queens and the goddesses alike.

Case Study 1: Arsinoe II

Arsinoe II was the daughter of Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305–282 BC), the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty. She was married three times to three different kings, first to Lysimachus, king of Thrace. Her second husband was Ptolemy Ceraunus, her half brother and the usurper of the Thracian throne after Lysimachus’s death. When he killed her two sons, she fled to Egypt and married her third husband, her full brother Ptolemy II (r. 285/82–246 BC).10 Even before Arsinoe II became queen of Egypt, she had been powerful, controlling entire cities and thus possessing vast wealth.11 That she married her half brother and subsequently her full brother was sensational and changed the position and perception of Ptolemaic queens fundamentally. When Ptolemy II married his sister, it was not to her benefit only but also to his, since the siblings could thus consolidate their power and strengthen Ptolemaic rule in Egypt. Already during her lifetime, Arsinoe became critical to the projection of the image of the Ptolemaic dynasty, including in regard to its maritime politics.12

Arsinoe II was associated with female members of the Greco-Egyptian pantheon, such as Aphrodite, Isis, and Hathor. She received temples of her own while sharing others with these goddesses. One of the most extraordinary images of Arsinoe II must have been planned for her sanctuary at Cape Zephyrium, near Canopus, east of Alexandria, where she was worshipped as Aphrodite. According to Pliny, a statue suspended by magnetic fields was to be positioned in the temple’s center, but this project was never completed.13 The temple and its cult image, which are attested only through literary sources, were dedicated by Callicrates of Samos, the supreme commander of the Ptolemaic royal navy from the 270s to the 250s BC, who had a particular interest in promoting this aspect of Arsinoe during her lifetime. Callicrates apparently took an active part in founding a network of strategic ports, many of which were named after the queen, thus helping to spread Arsinoe’s cult.14 It seems that he sought to mediate between old Hellas and the new world of Ptolemaic Egypt by bridging the gap between the two: spreading his rulers’ novel cultural policies abroad and at the same time bringing Greek tradition to bear on his Egyptian milieu.15

Aphrodite was known as a patron of the sea already from the Late Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age.16 Hellenic poets connected Arsinoe II to Aphrodite’s narrative as a marine and saving sea goddess,17 who both granted smooth sailing (euploia, which became one of Arsinoe’s epithets) and was venerated as a protectress of harbors—two suitable and important aspects for the Ptolemaic navy, which were conferred onto the deified queen. Arsinoe’s importance as a popular goddess of the Ptolemaic navy is also demonstrated by the numerous altars dedicated to Arsinoe Philadelphos throughout the eastern Mediterranean.18

Arsinoe’s power as a divine personality and her iconography were enhanced by her association with goddesses such as Isis.19 At the same time, Arsinoe’s lasting popularity as a deified queen and a divinity was particularly important in facilitating the broader development of Isis and her cult in the Mediterranean world.20 Arsinoe and the later Ptolemaic queens were venerated as Isis, as female embodiments of Ptolemaic power, and this must have reinforced Isis’s power in the minds of her followers and attracted even more worshippers to Isis generally. Thus Isis in her marine aspect, principally Greek in origin, was neither entirely Hellenic nor entirely Egyptian but essentially what her Hellenistic period worshippers formed her to be. This development was driven by political and economic implications and especially the shared semantic dimension of polytheistic religion. Due to their interacting networks of power, both Arsinoe II and Isis became attractive as sea goddesses, in and far beyond Egypt, with Arsinoe having functioned as a kind of theological interface.

Another example of the transfer of characteristics between Ptolemaic queens and goddesses is the Egyptian designation of Arsinoe II as “the perfect one of the ram,” which she received at Mendes, in the Nile Delta. The Mendes Stela is a vital source for Arsinoe’s deification and further events that took place under Ptolemy II. The text of the stela refers to several royal visits by Ptolemy II or the crown prince, who dedicated the temple in 264 BC and installed a new ram between 263 and 259.21 The monument was probably created to celebrate one or both of these events, and one can assume that rituals were conducted during these occasions, as depicted, at least in the form of a conceptual idea if not a real event, in the lunette.22 In line 11 Arsinoe is praised with the following epithets:

Her titulary is established as princess, great of favor, possessor of kindness, sweet of love, beautiful of appearance, who has received the two uraei, who fills the palace with her perfection, beloved of the ram, the whole one (= the perfect one) of the ram, sister of the king, great wife of the king, whom he loves, mistress of the two lands, Arsinoe.23

After being designated “beloved of the ram” (mrj(.t) bꜣ), Arsinoe is called “the whole one (= the perfect one) of the ram” (wḏꜣ(.t) bꜣ). This epithet is very rarely attested in Egyptian texts, usually as a designation of Isis:24 in the Ptolemaic temple at Aswan, the goddess is praised in a hymn dating to Ptolemy IV Philopator (r. 221–205 BC). One of Isis’s epithets is identical to Arsinoe’s on the Mendes Stela: “beloved of the ram, the perfect one of the ram.”25 In the temple of Kalabsha, dating to the time of Augustus (r. 30/27 BC–AD 14), an exact copy of this Aswan hymn can be found, with one exception: Isis is called “beloved of the ram, the perfect one of Khnum” mrj(.t) bꜣ wḏꜣ(.t) ẖnm, with Khnum replacing the Ram of Mendes as the local god in the second part.26 In the pronaos of the temple of Hathor at Dendera, which dates to the end of the Ptolemaic period, the epithets mrj(.t) bꜣ wḏꜣ(.t) bꜣ/ẖnm mrj(.t) are repeated twice in a hymn to Isis and its corresponding inscription.27 Cleopatra VII herself is praised there as “the female Horus, daughter of a ruler, adornment of the Ram/Khnum” (ḥr.t sꜣ.t ḥqꜣ ẖkr bꜣ/ẖnm).28

These attestations of the epithet “perfect one of the ram” in Aswan, Kalabsha, and Dendera appear in basically the same text but in different versions, with Kalabsha and Aswan preserving extended ones. Both Arsinoe II and Isis receive the epithets. Arsinoe’s title is, at least so far, first attested on the Mendes Stela, which was created under Ptolemy II. It is not until two generations later that Isis is attested with this title in her temple of Aswan, dating to Ptolemy IV. On present evidence it thus appears as if Arsinoe received this specific title first, but a series of connected epithets is known from the queens’ titularies in the Old Kingdom.29 The use of “the perfect one of the ram” for Isis was probably meant to strengthen the goddess’s role as a queen by assigning her an epithet of Arsinoe, the dynastically powerful queen par excellence, rather than the other way around.30 Isis’s universal rulership is described in Dendera, for example, where she is identified as “the Queen of Upper and Lower Egypt, the female sovereign of the sovereigns, the excellent female ruler who rules the rulers, mistress of lifetimes, female regent of years, who performs perfectness in the circuit of the sun disc.”31 In addition, Isis is described as “the queen of the rekhyt-people” (nb.tj rḫyt), which also evokes her royal power. This explains why her name is written in a cartouche when she is designated nb.tj rḫyt, but she remains also a mother who guarantees her son Harsiese’s ascent to the throne.32

The priority of Arsinoe as “the perfect one of the ram,” in contrast to Isis, could perhaps be compared with the transfer of the epithet Euploia (she of fair sailing) from Aphrodite to Isis via Arsinoe, as suggested by Laurent Bricault.33 The dynastic importance of the ram had a long-standing tradition, as expressed, for example, in the “Blessings of Ptah” text from the reigns of Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC) and Ramesses III (r. 1184–1153 BC), which outlines how Ptah begot the king by taking on the form of the Ram, the lord of Mendes.34 This divine procreation has affinities with the birth legend of the king, in which a supreme deity personally begets the king. Even if Arsinoe II was not the crown prince’s biological mother (Ptolemy III was born to Ptolemy II and his first wife, Arsinoe I), she was his ascriptive mother, and her presence emphasized his divine legitimation.

The queen was elevated by her connection with the sacred Ram of Mendes, whose ancient cult was, according to Manetho, initiated by a king of the 2nd Dynasty, dating it to the third millennium BC.35 It might go back even further since an image of a ram in a temple enclosure on a 1st Dynasty tag from Abydos may show the Ram of Mendes.36 The divine birth legend, well attested for the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC),37 also goes back much further, being attested by an Old Kingdom fragment found in the pyramid complex of Djedkare (r. 2380–2342 BC) in Abusir.38 We know that Egyptian priests of the first millennium BC were very learned about remote times. That they were very much aware of the ram’s significance is demonstrated in a liturgical papyrus of the late fourth century BC in which it is stated that the Ram of Mendes is the true manifestation of Re, hidden in the house of the Ram (ḥw.t-bnbn), the lord of Mendes.39 If the title “perfect one of the ram” describes a specific royal relation with the ram, possibly as a priestess, Arsinoe was most likely initiated and thus had access to secret locations and restricted knowledge. Being initiated supported her claim for legitimacy.40 Especially under rulers of foreign origin, it was important to uphold the proper order, which was reinforced by demarcations, and in the Egyptian ideology decorum demarcates the significant world of the king and the gods from the supportive role of humanity.41 By being a priestess and thus being initiated, Arsinoe could overcome some of these demarcations and hence claim legitimacy, not only for herself but also for the royal house.

The epithet “perfect one of the ram” for Arsinoe originated, it seems, in the Nile Delta, with a strong emphasis on the Ram of Mendes. The cultural center in the 30th Dynasty (380–343 BC) and the Ptolemaic period was in the north, and the most creative regions were probably in the Memphite area and the Delta. But it was not only in the Delta that Arsinoe received specific attention. The temple of Isis at Philae, just south of the First Cataract, was considerably enlarged under Ptolemy II. As a synnaos thea, his sister-wife shared the temple with Isis and participated in her veneration, as demonstrated by the hymns to Isis in her temple at Philae.42 In this temple, Arsinoe II was also incorporated into the reliefs of both the sanctuary and the so-called gate of Philadelphus.43 How much the Delta traditions might have influenced the theological development of the temple of Isis at Philae is demonstrated by one of the goddess’s epithets in the Demotic proskynema of a Meroitic envoy in Philae. All recorded embassies indicate that in the second half of the third century AD the estates of the temples of the Dodekaschoinos (Greek for “twelve-mile land,” referring to the northern part of Lower Nubia, which formed a cultural and political border between Nubia and Egypt) were controlled by a group of priests in Philae, which also comprised high officials as representatives of the Meroitic king.44 The Demotic graffito 416, dating to the mid-third century AD and carved in twenty-six lines on the gateway of Hadrian (r. AD 117–38) (thus being the longest of all Demotic graffiti at Philae),45 provides various cult-topographical and historical details. Isis, the main mistress of Philae, who is praised with various epithets in this graffito,46 is designated in lines 1 and 2 as “the beautiful libationer in the place of offering,”47 a designation that is otherwise attested only in a hieroglyphic variant at Behbeit el-Hagar, in the Delta (qbḥ.t nfr.t m s.t n.t wꜣḥ jḫ.t).48 Ian Rutherford raises in his discussion of Philae’s religious history “that the sanctuary looks south, and is not linked in to the network of Egyptian religion.”49

This interpretation might be justified in some respects, but it has correctly been contested by Jeremy Pope, based on his analysis of the abovementioned Philae graffito 416. Arsinoe’s cult presence roughly five hundred years before the graffito supports Pope’s idea of a “shared cult practice and theological vocabulary which stretched from Behbeit el-Hagar through Philae,” not only as late as the “final centuries of Demotic literacy,” as he puts it, but also as early as the substantial building and decoration initiative under Ptolemy II.50 Philae was not detached from Egyptian religious practices, as Rutherford claims. On the contrary, it was well connected with other temples and their priests along the Nile, for instance, with the temple of Horus at Edfu, as one example demonstrates: during the construction and decoration of the pronaos under Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II (r. 170–163 BC, 145–116 BC), Horus of Edfu and Hathor of Dendera appear in the temple of Isis at Philae.51

Arsinoe II functioned as a kind of theological interface in an interacting network of power, so that both she and Isis became attractive as sea goddesses, not only in Egypt but also far beyond, attested in textual sources such as Posidippus’s epigrams and the description of the temple at Cape Zephyrium, once a very powerful visual statement. These aspects, which were part of the multifaceted layers of interaction between the Ptolemaic queens and the goddesses, help to demonstrate that an important role was created for Arsinoe II, who was not only presented as the protectress of Ptolemaic rule but also perceived as a vehicle to promote the dynasty. In combining ancient Egyptian traditions with the new requirements of the early Ptolemaic dynasty, female royal power became indispensable and was projected back onto the divine world, for example, by emphasizing Isis’s role as a queen. This also found its way into Egyptian temple inscriptions, attested from Kalabsha to the Delta through the entire Ptolemaic period.

Case Study 2: Cleopatra VII

Kara Cooney calls Cleopatra a “drama queen” and further writes: “This woman didn’t hide from her sensual nature or procreative abilities.”52 Cooney’s book was written for the general public and not with the intent to reduce a powerful ruler to a woman with sexual rather than political power. Indeed, the last Ptolemaic queen did use dramatic entrances and captured the attention of two of the most powerful Roman generals, Julius Caesar and Marc Antony, and she did bear their children. At the same time, she managed to preserve her kingdom, at least for a time, using these men and their power to strengthen her position as ruler of Egypt until Octavian, who would later become the emperor Augustus, conquered Egypt in 30 BC. While Arsinoe II was engaged in actively creating a new ideological framework for Ptolemaic queenship, Cleopatra VII, on the one hand, continued—more than two hundred years later—to build on precedents set by Arsinoe and other Ptolemaic queens. Like Arsinoe II, who was designated wḏꜣ(.t) bꜣ, she was connected with Khnum and praised as “the adornment of the Ram/Khnum” (ẖkr bꜣ/ẖnm), as discussed above. On the other hand, challenged by changing political situations, the last female Ptolemaic ruler also developed new modes of expression, using architectural sources and their cultural backgrounds to connect herself to Isis.

Acra Lochias, the ancient promontory in Alexandria, near present-day Cape Silsileh, was part of the inner basileia, or royal quarter, as described by Strabo in the time of Augustus.53 Cape Silsileh exists now only because there was from medieval times until the beginning of the twentieth century a constant filling of this subsiding narrow strip of land in an attempt to protect the Eastern Harbor with a sort of breakwater. Ancient remains, gathered from the neighboring shores, were dumped as filling material. In the Hellenistic period, the domestic part of the royal palace as well as a prison were on and near this promontory. In 1993, during the excavations for the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, which is placed on the mainland near the entry to the cape, the remains of a massive gate were found, which suggest that the Acra was closed off by a wall, at least until this gate went out of use in the late Ptolemaic period.54

According to Harry Tzalas, the director of the Hellenic Institute of Ancient and Medieval Alexandrian Studies (HIAMAS) missions from 1998 to 2014, the surveys conducted east of Silsileh revealed some four hundred architectural elements in the site Chatby 1. Among the largest is the tower of a monolithic diminutive pylon of red granite, 2.6 meters high, 1.54 meters wide, and weighing about seven tons.55 Tzalas generously shared information with me, stating that the tower of this diminutive pylon was first found and photographed by the divers of the Greek mission in November 2000, lying on the seabed east of the tip of the Silsileh promontory, at a depth of some 9 meters. It was first raised, photographed, drawn, and studied in May 2003 (figs. 4.1 and 4.2) and then placed again on the sea bottom. When permission for its transportation, conservation, and exhibition was obtained in December 2009, it was lifted again and transported to the Kom el-Dikka laboratory for desalination and conservation. It has since been exhibited in the Open-Air Museum at Kom el-Dikka (figs. 4.3 and 4.4).

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.1 Figure 4.2

Figure 4.2 Figure 4.3

Figure 4.3During the October 2002 campaign, a monolithic flight of five steps,56 also made of red granite, was spotted some 400 meters south of the pylon tower location. The steps are around 1.7 meters long and 80 centimeters wide. When they were raised, photographed, and drawn, the mission realized that they may have formed an integral part of the pylon entrance. After being studied, they were placed back on the seafloor until permission was granted in October 2014 to place them in the desalination basin of Kom el-Dikka. They are now exhibited next to the pylon tower in the Open-Air Museum at Kom el-Dikka (fig. 4.5).

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.5The excavator also found the architrave or threshold of a monumental door, again made of red granite and of an estimated weight of eleven tons. According to Tzalas,57 it may have once belonged to the tomb of Cleopatra VII, located in the temple’s vicinity. The cavities of the threshold where the huge door rested have retained the brass supports and the lead fillings. Due to lack of space for a permanent exhibition, this architectural element was placed again on the seafloor.

Because of the weight of these monolithic elements and their distance from the shore, the excavators assume that they had not been transferred and reused as buttress; nor can these heavy pieces be considerably moved by the action of the waves.58 They considered them as being roughly in situ, marking the site of specific buildings. Plutarch recorded that Cleopatra VII “had a tomb and monuments built surpassingly lofty and beautiful, which she had erected near the temple of Isis.”59 Cleopatra broke with the Ptolemaic tradition of being buried in the Sema, where Alexander and the previous Ptolemies were laid to rest, and had her tomb built separately.60 Acra Lochias was the least accessible part of the royal quarter, a fortified retreat for the Ptolemies, with very restricted access, as demonstrated by the massive gate mentioned above.

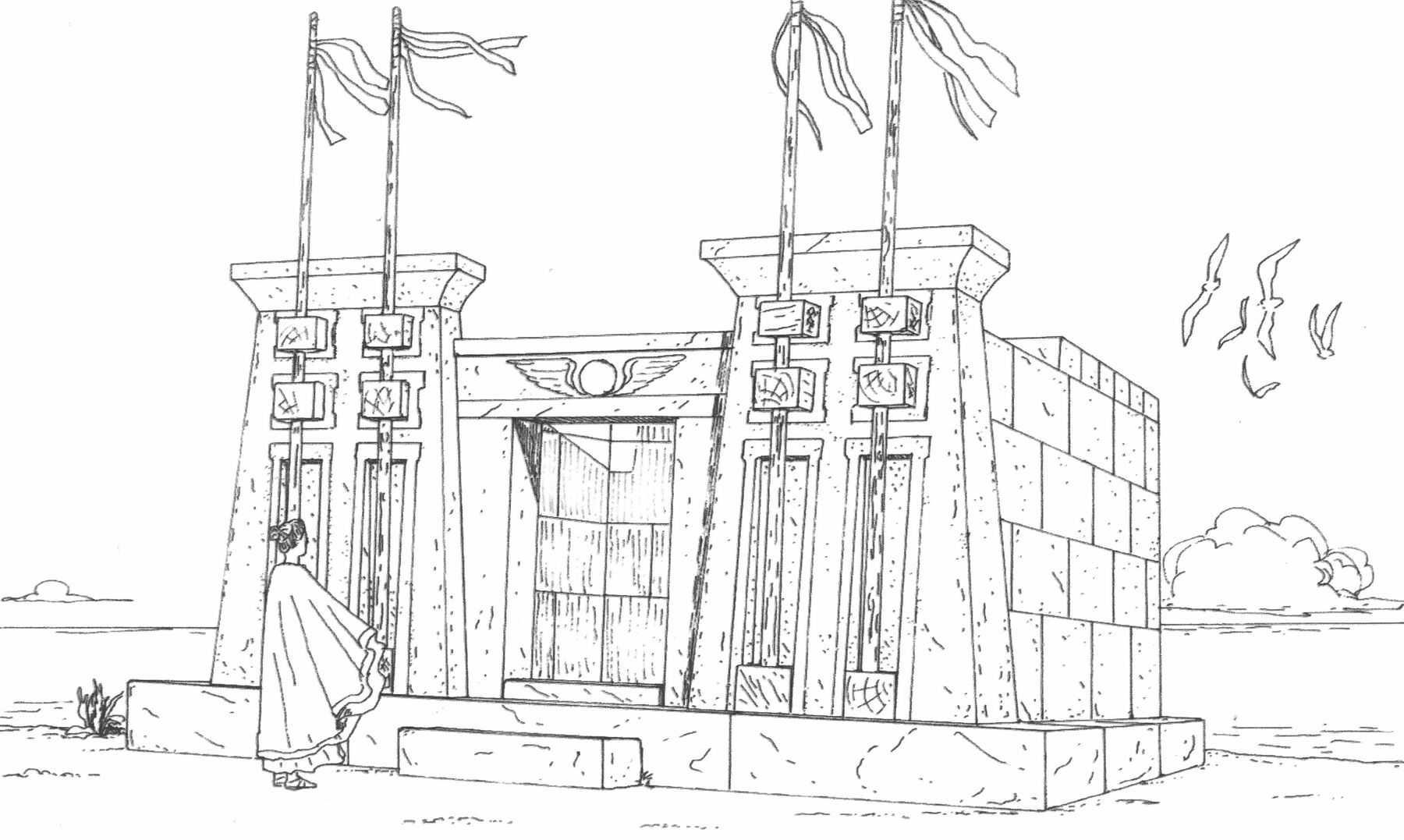

The diminutive pylon tower and the steps found underwater must have once been part of an Egyptian pylon, a typical architectural expression of Egyptian civilization from the New Kingdom onward, with precursors and roots reaching back to the Old Kingdom.61 But the pylon tower excavated in Alexandria is pretty much unique in its diminutive form.62 Together with a second tower, it would have once flanked a central portal or gate, to which the flight of steps, now exhibited near the tower, probably would have led. Like its monumental equivalents, the tower has a typical form with a rectangular foundation and sloping walls (see figs. 4.1–4.4). Its front contains large vertical recesses for wooden flagstaffs, from which pennants flew above the level of the top of the pylon.63 Above each recess were two rectangular slots, which, in monumental pylons such as the one at Edfu, were meant as light slots.64 Laetitia Martzolff calculates a height of 1.8 meters for the gate of the diminutive pylon tower, which she thinks is too low for it to be considered the monumental entrance to the temple.65 If the pylon and the steps are indeed parts of the Isis temple attested by Plutarch, it was a small temple or at least a temple with a small pylon, whose towers were in my opinion just high enough to allow for a gate that one could walk through. Since it may have been a rather private temple for the queen, this is entirely possible (see fig. 4.6 for a hypothetical reconstruction by Harry Tzalas).

Figure 4.6

Figure 4.6No real parallel for such a diminutive pylon is known so far, but a rather smallish pylon—at least in comparison to the monumental ones from the New Kingdom onward—is located in Karnak: on the east side of the courtyard between the seventh and the eighth pylons, a gate opens to the barque shrine of Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BC) at the sacred lake (figs. 4.7 and 4.8).66 The small pylon comprises two towers, inscribed on their western face, and a gate in the middle, to which a flight of steps leads from the east. The towers are not preserved to their full height but do retain their full width: the north one is 3.87 meters wide, the south one 3.75 meters, and the gate in the middle 2.33 meters; in sum, the pylon is 9.95 meters wide. At 1.54 meters, the pylon tower in Alexandria measures less than half that width, so the gate to the Isis temple would have been very small indeed but wide enough for access.

Figure 4.7

Figure 4.7 Figure 4.8

Figure 4.8Three further finds worth noting in the context of the diminutive pylon might shed some light on the existence of (very) small or even miniature forms in an architectural context. First, a pylon-shaped block of sandstone was found among the stones used in the Christian period to fill in the north doorway of the enclosure wall of the temple of Hibis in the Kharga Oasis.67 Its counterpart was discovered in the northwest corner of the corridor formed around the temple by this wall. The blocks are 95 to 100 centimeters long and 66 to 67.5 centimeters high. As with a temple pylon, the outer ends and the fronts slope inward; on each face was a pair of slots for wooden flagstaffs. Herbert Winlock calculated that they probably formed the front of a temple-shaped shrine about 2.25 meters wide, with the interior chamber measuring 1.3 by 1.3 meters. Based on the taper of the pylon ends, Winlock estimated that it would have been only 90 centimeters high, but the shrine probably stood on a pedestal, which could also have been inscribed.68 No inscription that would reveal its date, purpose, or dedicator was found. The blocks’ original location is uncertain, but Winlock opined that they possibly came from hypostyle hall M or N.

Second, a quartzite base of a wooden naos, once part of a sanctuary in Heliopolis, attests to a pylon-shaped facade that is now lost, but the indentation on the base’s upper face shows the outlines of a pylon. This object, originally excavated by Joseph Hekekyan in 1851, was once misunderstood as the base for an obelisk,69 but the temple-shaped shrine found in the temple of Hibis illuminates its original purpose.

Third, two altars in the forms of pylon towers were erected under Ptolemy IV in the temple of Montu at Tôd.70 Each is inscribed with hymns and stands around 1.35 meters high, so that offerings could easily be placed on them (fig. 4.9).71 The small pylon found underwater in Alexandria is, however, too large for an altar and does not seem to fit into the context of a naos, so the interpretation of it as belonging to a small temple is preferable.

According to Arrian,72 Alexander the Great himself founded a temple for Isis in Alexandria, but its exact location is not attested. Whether this temple is identical to the Isis sanctuary discussed above or was the one in which the priestly synods met at least twice, as attested in the Alexandria decree (243 BC)73 and in Philensis II (186 BC),74 is also unclear. Judith McKenzie, in her seminal work on Alexandria, expressed the view that the Isis temple, already founded in the Ptolemaic period, was probably the Egyptian one depicted on Roman coins minted in Alexandria.75 These coins date to the reigns of Trajan (r. AD 98–117) and Hadrian (r. AD 117–38) and show a pylon that corresponds in its architectural form to an Egyptian temple entrance. This could suggest that it was built from the start in Egyptian style. On the roof of the gate between the two pylon towers appears a figure of Isis.76 These coins could possibly be linked to the small Egyptian pylon found underwater, which could have once belonged to a temple of Isis of rather small dimensions. This small Isis temple must have been different from the one in which the priestly synods reportedly met, because they could have assembled only in a larger compound.

From the literary evidence—now perhaps supported by architectural finds—it is clear that a temple for Isis once stood in (or near) the basileia, with Cleopatra’s tomb being built in its direct vicinity, thus participating in the sacred surroundings. Since the temple is connected to Acra Lochias, Tzalas and others assigned the epithet Lochia (midwife) to Isis and her temple in this specific case, assuming that it refers to the nurturing aspect of Isis, the mother of Horus.77 Michel Malaise has argued, however, that Lochia as an epiclesis for Isis is attested in Macedonia only.78 Svenja Nagel, who published a detailed study on Isis in the Roman Empire in 2019, agrees with Malaise and thinks that the temple was probably dedicated to the marine Isis, who was created in Alexandria on the basis of her association with Aphrodite.79 This would relate back to Arsinoe II, so it seems a tempting possibility, but it remains unclear with which epiclesis Isis was venerated at Acra Lochias and her temple—either as Soteira, Euploia, or perhaps, but rather unlikely, as Lochia(s)—but once again Cleopatra VII employed the well-established relation between Ptolemaic queens and Isis.80 Marc Antony was celebrated as Neos Dionysos and Cleopatra as Nea Isis.81 Publicly they appeared in the guise of this divine couple. Although the title of a “New Isis” is not attested for Cleopatra VII in contemporary literary sources or inscriptions, it was projected onto her by Cassius Dio and Plutarch.82 In these classical sources, heavily influenced by the Roman worldview, Cleopatra is shown as a kind of catalyzer who was used to effect Marc Antony’s change in character,83 but this negates to a large extent the extraordinary role she played in the last years of the Ptolemaic Empire and the self-presentation she orchestrated, which was based on the traditions of the Ptolemaic queens and combined with new elements.

Regarding the size of the pylon tower, a different interpretation comes to mind, leading us to a location to the far south of Alexandria and Egypt, to the royal cemeteries of Meroe with their pyramids and funerary chapels. Pyramids first appear as part of Nubian royal burial practices in the seventh century BC. In the 25th (Nubian) Dynasty, Taharqa (r. 690–664 BC) began the tradition of placing pyramids over the tombs of the rulers and members of the royal family. With an estimated height of 50 meters, his pyramid at Nuri—north of the Fourth Cataract of the Nile near the temples of Gebel Barkal, the sacral center of the Kushite Empire—is the largest such structure in Sudan.84 In the Meroitic period (third century BC to the fourth century AD), the royal cemetery was relocated from the region around Gebel Barkal to the south into the region of Meroe: at Begrawiya, north of the Sixth Cataract, 147 royal pyramid chapels survive.85 Pyramid Beg. S10, dedicated to the ruling queen Bartare (r. 284–275 BC), is located in the southern cemetery, the earliest and largest part of the Begrawiya necropolis.86 In front of a pyramid with stepped sloping-face courses and a lateral length of 10.45 meters, stands a chapel made of sandstone masonry with a small, rather elongated pylon and recessed doorway.87 The southern pylon tower is largely destroyed, but the northern one is partly preserved, so that a width of about 2 meters and a height of about 3.4 meters can be reconstructed,88 slightly larger than the Alexandrian monolithic one, which is 1.54 meters wide and 2.6 meters high. The pylon of Pyramid Beg. N19 of King Tarekeniwal (second century AD) at the royal pyramid cemetery of Begrawiya North,89 which is almost completely preserved (fig. 4.10), is marginally higher than that of Beg. S10 and even more elongated: its pylon towers are about 1.7 meters wide and about 3.7 meters high, with a gate in the middle of about 1.8 meters high—a height that Martzolff calculated also for the Alexandrian gate but dismissed as too small.90

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10Even if both Meroitic examples are slightly bigger than the Alexandrian pylon tower and even if the Meroitic pylon towers were not monolithic, this comparison demonstrates that the size of the Alexandrian tower was sufficient to allow access to a building. This could very well have been a temple for Isis, as discussed above, but one could also wonder whether the diminutive pylon decorated Cleopatra’s funerary chapel and not the temple of Isis. We do not know what her tomb once looked like, but the Meroitic examples show the possibility of chapels accessible through small pylons. This comparison does not necessarily seek to insinuate that the Meroitic pylons provided inspiration for the Alexandrian pylon tower, but it might be a possibility, even if only a remote one. A friendship between Cleopatra VII and the kandake Amanishakheto is assumed.91 The Sudanese queen was buried in the northern cemetery of Begrawiya in tomb Beg. N6, which comprises a pyramid, a funerary chapel, and a small pylon as described above for other burials at this site.92

It has been suggested that Cleopatra’s activities as a queen could have been inspired by the role of the Meroitic kandake.93 The title kandake, whose meaning is still not entirely clear, probably designated the mother of the ruling king, and several kandakes were crowned as queens, but their exact status remains unclear, namely whether they ruled in tandem with the king or held power alone.94 Like the Ptolemaic queen, the Meroitic kandake was closely connected with Isis, the mother of Horus and thus of the living king. Isis became the most important female goddess in the Meroitic kingdom, not only as the king’s protectress.95 Dietrich Wildung mentions in this context the exceptional position of women in the societies of the middle Nile, which may have influenced Egyptian architecture already in the New Kingdom, at a time when Egypt colonized the Nile Valley south of the First Cataract.96 Two Nubian temples substantiate the importance of Tiye, the wife of Amenhotep III of the 18th Dynasty. At Soleb, near the Third Nile Cataract in present-day Sudan, a large temple was dedicated to Amun-Re and Nebmaatra, a deified form of this king. Amenhotep III, who was given the status of a moon good complementary to his solar aspects, built a temple to his wife as a pendant to his own, a few kilometers to the north at Sedeinga.97 There the focus was on the “King’s Great Wife,” presumably as the deified solar eye of Re, Hathor, or Tefnut. The rituals at Sedeinga turned the angry eye of Re, which had fled Egypt from the violent leonine nature of Tefnut, into the appeased and loving form of Hathor and thus reestablished world order. The deified Tiye became Hathor, the perfect consort of the king. In the colonial land of Nubia, which was potentially violent, the temples of Tiye and Amenhotep III enacted cosmic order.98 The construction of these two Nubian temples for Amenhotep III and Tiye was followed a century later by the temples for Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, where the larger temple was dedicated to the king and the smaller one to his wife, Nefertari, as Hathor. In this temple, the queen is shown conducting rituals jointly with her husband but also alone. She acts as Hathor, who is also the protectress of the newborn king, as depicted in the birth chamber or southern chapel.99 In Egypt itself, no such temples for the queens Tiye or Nefertari exist, so one could assume that Nubian traditions were more encouraging for the elevation of a living queen’s status.

It is not necessary to base Ptolemaic female power on Kushite or Meroitic patterns in order to explain Cleopatra’s prestige and status. It is, nonetheless, an alluring option—given the importance of Meroitic queens—that Cleopatra might additionally have been inspired by the powerful female rulers from Egypt’s neighbor to the south. She may even have visited Nubia briefly, and according to Adam Łukaszewicz, we may assume that she “had a detailed knowledge of geography and a perfect orientation in the realities of the Kushite kingdom.”100 Based on buildings, statuary, reliefs, and decorated pottery preserved from the last two centuries BC, László Török referred not only to the continuity of trade between Egypt and Meroe but also to the diplomatic contacts or royal gift exchange and the connection between sanctuaries, resulting in the adoption of Egyptian technologies and decorative styles.101 Analysis of the diminutive pylon from Alexandria might contribute to a new area of inquiry into the roles and (self-)presentations of the queens of both the Ptolemaic and the Meroitic kingdoms, with attention to the possible influence of ancient Sudan on Ptolemaic ideas of queenship and vice versa.

The underwater excavations in Alexandria substantiate the literary sources, which refer to the tomb of Cleopatra VII next to a temple of Isis. Like Arsinoe II and her supporters, who designed the extraordinary temple at Cape Zephyrium, the last Ptolemaic queen and her advisers created new modes of expression for female Ptolemaic power. They built on existing patterns but did not hesitate also to break with centuries-old Ptolemaic traditions—for example, of being buried together with Alexander the Great. The creation of Cleopatra’s separate tomb shifted the emphasis away from Alexander and the Ptolemaic dynasty to a new beginning. The queen was still closely associated with the goddess Isis, as was Arsinoe II, whose newly created epithet “the perfect one of the ram” was transferred to the goddess herself two generations later and used for both royal and divine women for more than two and a half centuries. The royal connection with Isis was also emphasized further south, in the Nubian kingdom, which had been influenced by Egypt and vice versa over a long period. Whether the Meroitic architectural elements, such as the small pylons, (re)influenced tomb or temple buildings in Egypt, needs to be further researched, but it is one alluring option for analyzing the exceptional monolithic pylon tower found underwater in Alexandria. Both Arsinoe II and Cleopatra VII shaped the royal Ptolemaic ideology, Arsinoe more lastingly than Cleopatra because the Hellenistic period in Egypt came to an end with Cleopatra’s death and the emerging Roman Empire.

Using very different examples from diverse backgrounds and places across Egypt and Meroe, I have tried to illuminate the complex interrelations between two powerful Ptolemaic queens—Arsinoe II and Cleopatra VII—and Isis, Hathor, and Aphrodite. In the queens’ relations with these goddesses, old traditions were used and innovative ideas employed, a process that ultimately led to the creation of new understandings of the queens and goddesses and new “cultural codes.” In the Hellenistic period, both Arsinoe II and Isis became popular as sea goddesses, in and far beyond Egypt, with Arsinoe having functioned as a kind of theological interface in the interacting networks of power. The ideas of the admiral Callicrates, which led to the creation of a temple of Arsinoe-Aphrodite at Cape Zephyrium, were most probably influenced by the Ptolemaic court, as were the temple buildings along the Nile, for example, the one for Isis at Philae, which also highlights the importance of Arsinoe II for the dynasty. Posidippus and other Hellenistic poets, such as Theocritus and Callimachus, who praised the dynasty in their poems, were supported by the king, so we can also expect that they were influenced by the court. Whether by poetry, cults, architecture, or other means, the Ptolemaic officials and dependents experimented with a variety of symbols and formats to promote their royal house, from the beginning of the dynasty right until the end. Cleopatra VII built on these processes and erected her tomb next to a temple for Isis near the sea. Whether the diminutive pylon tower excavated in the sea belonged to her tomb or to the Isis temple, it attests to the architectural modes of expression used by and for the Ptolemaic queen. The question of whether she was inspired by Meroitic ideas, themselves resulting from long-standing connections between Egypt and Meroe, needs to be further investigated.

These brief case studies demonstrate the intricate patterns that were created to interweave queenship in the royal and divine worlds, which influenced each other. The associations of the Ptolemaic queens and goddesses need to be further illuminated in more detail. For these studies of the Ptolemaic royal women, we need to trace the diachronic continuities and discontinuities that overlap in different layers, which have not all been recognized so far. Ancient Egyptian culture also has an analytical advantage in terms of mnemohistory, since it forms the past to which the Ptolemies, the Mediterranean rulers of Egypt with Macedonian ancestry, referred in different ways.102 Hence they were challenged to self-reflection. For the Ptolemies, Egypt became part of their own origin, into which they incorporated Greco-Macedonian and other elements. In contrast, when Octavian conquered Egypt, it developed into an icon of subjugated power, and this created the need for different cultural concepts and codes.103

Dedicated to the memory of Judith McKenzie, who passed away far too early, in 2019.

I wish to thank Jeffrey Spier and Sara E. Cole for inviting me to the J. Paul Getty Museum for a very stimulating conference in August 2018. I am very grateful to Kenneth Griffin and René Preys for reading a draft of this chapter; to Harry Tzalas for sharing information and photographs of his underwater excavations at Alexandria and giving permission to publish some of them (figs. 4.1, 4.2, 4.5, 4.6); to Amr Saber Zaki Attalah for the photographs of the pylon in Alexandria (figs. 4.3, 4.4) and to the Permanent Committee Cairo and Ms. Nashwa Gaber (director of foreign mission affairs) for the permission to publish these; to René Preys for providing a photograph (fig. 4.7); to Luc Gabolde for architectural discussions and the permission to publish the photographs of Karnak (figs. 4.7, 4.8); to Christophe Thiers for the photograph of the altar at Tôd (fig. 4.9); to Alexandra Riedel and Pawel Wolf of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) / Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan (QMPS) for information on the Meroitic pyramids and a photograph (fig. 4.10).

Notes

Appian, The Civil Wars 2.102: “He placed a beautiful image of Cleopatra by the side of the goddess, which stands there to this day” (cited after https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Appian/Civil_Wars/2*.html). Cassius Dio, Historiae Romanae 51.22.3: “Thus Cleopatra . . . she herself is seen in gold in the shrine of Venus” (cited after http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/51*.html). ↩︎

, 290. ↩︎

, 294. ↩︎

The divine birth is attested from the Old Kingdom onward; see , 155–64; , 171–88. A full version of the myth is known from the reign of Hatshepsut in the 18th Dynasty; see . For the Old and Middle Kingdom traditions in Hatshepsut’s temple, see , 61–93 (esp. 78–80 for the birth cycle). ↩︎

For the context, see , 653–57. ↩︎

, 1–24. ↩︎

, 197–211. ↩︎

, 132, 150. For the queen as female Horus, see , 88–97; , 24–57; , 199–238. ↩︎

See, for example, and . ↩︎

, 35–36. ↩︎

, 14; , 36–40. ↩︎

, 99–127. ↩︎

Pliny, Natural History 34, 148. For a reconstruction, see , 61–69. For a Hellenistic hymn to Arsinoe-Aphrodite, see , 135–65. ↩︎

, 41–46; , 52. See also , 1221. ↩︎

, 243–66 (esp. 244). ↩︎

. See also . ↩︎

For a short summary and discussion of the different poetic sources, see , 215–16. In his epigrams 116 and 119, the Hellenistic poet Posidippus, generally placed before Arsinoe’s death in 270 BC, celebrated her temple at Cape Zephyrium, and Arsinoe is promoted as a marine goddess. For a translation of these epigrams, see , 43–44. See also , 245–48. ↩︎

, 187–201; see also , 97. ↩︎

See, for example, , who discusses the iconography of assimilation in the case of Isis and the royal imagery of Ptolemaic seal impressions. See also J. Spier in , 192, no. 130. ↩︎

For the Egyptian and Hellenized Isis and her cults in the Greco-Roman world, see also Bommas in this volume. ↩︎

, 257–60. ↩︎

I have already analyzed the lunette and both the divine and royal aspects of the depiction of Arsinoe II; see , 151–57; . ↩︎

, II 39,12–40,4. For a detailed discussion of Arsinoe II’s epithets, see , 151–57. ↩︎

According to , 2:649b, s.v. wḏꜣ.t bꜣ “Die Pflegerin (?) des Ba” refers to Isis only, not Arsinoe II. ↩︎

, 80–81, C11: between wḏꜣ(.t) and bꜣ there is a lacuna. For a translation and a discussion, see , 122 (esp. n. 566), where she translates “die Pflegerin des [Chnu]m(?).” ↩︎

, 15–16. ↩︎

Frieze inscription on the west wall of the pronaos (, 146, 8) and in the western part of the soubassement of the southern exterior wall of the naos (, pt. 2, 6); , 199, translates “l’aimée du Bélier, qui prend soin de Khnum.” ↩︎

, pt. 1, 5. The head of the seated god is destroyed, but the epithet ẖkr bꜣ/ẖnm is repeated on the western side (, pt. 2, 10) with the same ram-headed seated god as in wḏꜣ(.t) bꜣ. ↩︎

See ; , 153, 164. ↩︎

On Isis’s role as a queen, see ; , 146–47; , 267 (with n. 1337). ↩︎

, 110, 6–7 (= , 144–45). ↩︎

, 327–51, esp. 331. To a much lesser extent, Hathor could also be designated as nb.tj rḫyt in the temple of Hathor at Dendera but only where she took the place of Isis. For Isis and Hathor being adored by the rekhyt- and pat-people, see, for example, , 33, 50–51, 95–96. ↩︎

See , 23–42. ↩︎

For the “Ptah-Dekret,” see , 64–66; , 28–37 (esp. 30–44); , 155–56. ↩︎

Manetho, fragment 9: , 37. See also , 178–80. ↩︎

, 25–26, plate VII. See also , 29–46 (esp. 35, fig. 4). ↩︎

For the evidence, see . ↩︎

, 275–87. ↩︎

P. BM EA10252, col. 4, 16–20: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA10252-4; , 217. For the context of the hieratic ritual books of Pawerem attested on P. BM EA10252 and other papyri, see also , 11, and , 133–42. For P. BM EA10252 in general, see Trismegistos no. 57226: https://www.trismegistos.org/hhp/detail.php?tm=57226. ↩︎

See , 165–73. ↩︎

, 21. ↩︎

See , 12–15, 89–90. ↩︎

, 3, 12. For detailed references, see also , 151. ↩︎

For the situation of Philae and Lower Nubia in Roman times, see , 443–73 (esp. 468–69). ↩︎

Philae 416 = , 1:111, 114–19, 2: plate lxiv. ↩︎

See , 677–78. ↩︎

, 75, commentary B. ↩︎

, 7:184b. ↩︎

, 236. ↩︎

, 103. ↩︎

, 7–15. ↩︎

, 253, 255. ↩︎

Strabo, Geography 17,1,9. For a recent interpretation of the ancient sources and a discussion of the single monuments located in the basileia, see , 53–61, 123–324. ↩︎

, 12–13, 18, 26, 39, 66. ↩︎

, 327–28, 341, fig. 6, 342, fig. 9; . , 76, previously stated a weight of four tons. See also , 320–21 (with fig. 163). ↩︎

, 327–28, 341, fig. 6, 342, fig. 9. ↩︎

, 328, 342, fig. 8; see also , 19, fig. 8. ↩︎

, 328, 341, fig. 7. ↩︎

Plutarch, Life of Antony 74, 1–2. Cited from http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Antony*.html. For Cleopatra’s tomb in the royal quarters, see also Cassius Dio, Historiae Romanae 51.8: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/51*.html. ↩︎

, 126–36. ↩︎

, 17–60. See also , 141–51; , 135–64. ↩︎

The wooden pylon model from the tomb of Tutankhamun is a cult object (, 87, plate 53A; see , 55–79) and cannot be compared in its size to the diminutive one in Alexandria. ↩︎

For an ancient Egyptian depiction of a pylon with flagstaffs and pennants, see , 57, fig. 27 (tomb of Panehsy). ↩︎

, 75 (see Taf. 6a for an illustration of the slots’ function). ↩︎

, 139, 155. See in contrast , 320, who assumes that “der kleine Tempel vermutlich eher den Charakter eine [sic] Kapelle gehabt haben dürfte und wohl kaum zu den bedeutenden und somit und somit erwähnenswerten Heiligtümern der Stadt gezählt haben wird.” ↩︎

, 173 (509)–(511). , 266: “un pylône en miniature.” I am grateful to Luc Gabolde for drawing my attention to this pylon in March 2019 and for granting me permission to take photographs. ↩︎

, 40, plate LI. ↩︎

, 40. The corners of the blocks had a torus molding, which indicated that on top of each there was originally a cavetto cornice. ↩︎

See , 119–21, figs. 18, 19; , 392, no. xviii–xx–1.1 (“Naosbasis, Matariya in situ”), 477 (1966–1972): Raue gives only the measurement for the entire base (415 × 320 cm), not the traces of the naos, which is far smaller, judging from fig. 19 of , not even less than half the size, which would be smaller than the temple-shaped shrine in Hibis (see notes 67 and 68 above). ↩︎

, 36–42. See also , 99. For the context, see also , chapter 4.3.8. ↩︎

I am very grateful to Christophe Thiers for his photographs of these altars and his comments. ↩︎

Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander 3.1.5. ↩︎

, 76–83. ↩︎

See , 240–46. ↩︎

, 39, fig. 39, 78; , 86, also presumes that the pylon dates to the Greco-Roman period “since Egyptian temples would never have had such a monolithic piece in such small dimensions.” ↩︎

, 181–90; , 61, plate 11.4. See , 72–75, for an interpretation of the figure above the gate, which he and Naster (, 186–87) interpret as the epiphany of the respective goddess. ↩︎

According to , 111, it is the temple of Isis Soteira, with which , 136, agrees. , 25, calls her Isis Lochias. ↩︎

, 149–51. ↩︎

, 714–15, who also mentions Isis Pharia as another possibility. ↩︎

Coins of Cleopatra VII with Hathor’s typical crown and Isis’s epithets are attested after the birth of Ptolemy XV Caesarion from 47/46; see , 290; , 222. See also , 318, who refers to the Hathor temple in Dendera, where Cleopatra VII and Isis (, pt. 2, 212) correspond to each other, Cleopatra as the queen on earth and Isis as the queen in the divine realm. ↩︎

; , 291 (with references to the classical sources). See also , 134–35; , 348. ↩︎

Plutarch, Life of Antony 54, 6: “Cleopatra, indeed, both then and at other times when she appeared in public, assumed a robe sacred to Isis, and was addressed as the New Isis” (cited from http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Antony*.html.). Cassius Dio, Historiae Romanae 50, 5, 3: “He posed with her for portrait paintings and statues, he representing Osiris or Dionysus and she Selene or Isis” (cited from https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/50*.html). ↩︎

See also , 208. ↩︎

, 12. See also , 91–98, for a discussion of the different heights of the pyramids; , 207–14. ↩︎

, 555; , 297. For reconstruction drawings of parts of the northern cemetery with pyramids, chapels, and pylons, see , 411, fig. 68, 415, fig. 73. For a summary of the funerary architecture in Meroe, including the pylons, see , 789–94. ↩︎

Queens and other royal family members were first buried in Begrawiya. Beginning with Ergamenes I (or Araqamani I), a contemporary of Ptolemy II, the Meroitic kings were also laid to rest at Begrawiya. From Ergamenes II onward, a contemporary of Ptolemy IV Philopator, the tomb chapels at Begrawiya were decorated in more intricate ways, including the introduction of Osirian themes (for references, see , 22, 109; , 188–92). When Ergamenes II gained control over the Dodekaschoinos, he was actively involved in the extension and decoration of the Nubian temples at Philae and Dakka, also by using texts and epithets developed by and for the Ptolemies (for a discussion, see , chap. 4), thus inserting himself further into Egyptian traditions. These correlations warrant further investigation. ↩︎

, 6, 46–47, with fig. 22; , 15, fig. 3, plates x–xii. See , 560, fig. 3, for a discussion of the queen’s title or name. ↩︎

I am grateful to Alexandra Riedel and Pawel Wolf of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) / Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan (QMPS), who kindly supplied information and plans for Beg. S10 and N19 as well as fig. 4.10. ↩︎

, 7, 142–45, with fig. 93 (Dunham referred to the king as Amanitenmemide). ↩︎

See , 155 (see note 65 above). ↩︎

, 694. ↩︎

Amanishakheto’s vast collection of gold jewelry was discovered in her tomb in 1837; see , 302–40; , 285. ↩︎

, 694. See also , 68: at least nine ruling queens are known by their tombs in Meroe, dating to the period between the end of the second century BC and the beginning of the fourth century AD. ↩︎

For the kandake in general, see , 200–205. For the kandake Amanishakheto, see , 30–31; , 456–59; , 99–102. ↩︎

, 292. ↩︎

, 203. ↩︎

, 106–10. ↩︎

, 110. For a discussion within the context of female rulers in Egypt, see , 27–28. ↩︎

, 57–60, 68–69, figs. 7, 8. ↩︎

, 695. ↩︎

, 447–48, 516–30. See also the decoration of the Meroitic tomb chapels from Ergamenes II onward with extended Egyptian topics and his interests in decorating the Nubian temples of Philae and Dakka (see note 86 above). ↩︎

, 6. ↩︎

See, for example, , 7–15, and , 230–37, for the concept of “inventing traditions” and Rome as a “successor culture” that was constantly looking back and around, trying to formulate its own identity vis-à-vis the Mediterranean, the Near East, Egypt, and Europe. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Albersmeier 2002

- Albersmeier, Sabine. 2002. Untersuchungen zu den Frauenstatuen des ptolemäischen Ägypten. Mainz: Zabern.

- Altmann 2010

- Altmann, Victoria. 2010. Die Kultfrevel des Seth: Die Gefährdung der göttlichen Ordnung in zwei Vernichtungsritualen der ägyptischen Spätzeit (Urk. VI). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Ashby 2020

- Ashby, Solange. 2020. Calling Out to Isis: The Enduring Nubian Presence at Philae. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias.

- Baines 1990

- Baines, John. 1990. “Restricted Knowledge, Hierarchy, and Decorum: Modern Perceptions and Ancient Institutions.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 27:1–23.

- Baines 1991

- Baines, John. 1991. “On the Symbolic Context of the Principal Hieroglyph for ‘God.’” In Religion und Philosophie im alten Ägypten: Festgabe für Philippe Derchain zu seinem 65. Geburtstag am 24. Juli 1991, edited by Ursula Verhoeven and Erhard Graefe, 29–46. Leuven: Peeters.

- Barbantani 2005

- Barbantani, Sylvia. 2005. “Goddess of Love and Mistress of the Sea: Notes on a Hellenistic Hymn to Arsinoe-Aphrodite (P. Lit. Goodsp. 2, I-IV).” Ancient Society 35:135–65.

- Barguet 1962

- Barguet, Paul. 1962. Le temple d’Amon-Rê à Karnak: Essai d’exégèse. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Beckerath 1999

- Beckerath, Jürgen von. 1999. Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Mainz: Zabern.

- Beinlich 2008

- Beinlich, Horst. 2008. “Horus von Edfu in Philae.” In Diener des Horus: Festschrift für Dieter Kurth zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Wolfgang Waitkus, 7–15. Gladbeck: PeWe.

- Bing 2002–3

- Bing, Peter. 2002–3. “Posidippus and the Admiral: Kallikrates of Samos in the Milan Epigrams.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 43:243–66.

- Bisson de la Roque 1941

- Bisson de la Roque, Fernand. 1941. “Note sur le dieu Montou.” Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 40:1–49.

- Bommas 2013

- Bommas, Martin. 2013. “Isis in Alexandria—Theologie und Ikonographie.” In Alexandria, edited by Tobias Georges, Felix Albrecht, and Reinhard Feldmeier, 127–47. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Brenk 1992

- Brenk, Frederick E. 1992. “Antony-Osiris, Cleopatra-Isis: The End of Plutarch’s Antony.” In Plutarch and the Historical Tradition, edited by Philip A. Stadter, 159–82. London: Routledge.

- Bresciani and Pernigotti 1978

- Bresciani, Edda, and Sergio Pernigotti. 1978. Assuan. Pisa: Giardini.

- Bricault 2020

- Bricault, Laurent. 2020. Isis Pelagia: Images, Names and Cults of a Goddess of the Seas. Translated by Gil H. Renberg. Leiden: Brill

- Brunner 1991

- Brunner, Hellmut. 1991. Die Geburt des Gottkönigs: Studien zur Überlieferung eines altägyptischen Mythos. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Bryan 1992

- Bryan, Betsy M. 1992. “Designing the Cosmos: Temples and Temple Decoration.” In Egypt’s Dazzling Sun: Amenhotep III and His World, edited by Arielle P. Kozloff and Betsy M. Bryan, 73–111. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Busch and Versluys 2015

- Busch, Alexandra, and Miguel John Versluys. 2015. “Indigenous Pasts and the Roman Present.” In Reinventing the Invention of Tradition? Indigenous Pasts and the Roman Present, edited by Dietrich Boschung, Alexandra Busch, and Miguel John Versluys, 7–15. Paderborn: Fink.

- Carney 2013

- Carney, Elizabeth Donnelly. 2013. Arsinoë of Egypt and Macedon: A Royal Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carter 1933

- Carter, Howard. 1933. Tut-Ench-Amun: Ein ägyptisches Königsgrab. Vol. 2. Leipzig: Brockhaus.

- Cassor-Pfeiffer and Pfeiffer 2019

- Cassor-Pfeiffer, Silke, and Stefan Pfeiffer. 2019. “Pharaonin Berenike II: Bemerkungen zur ägyptischen Titulatur einer frühptolemäischen Königin.” In En détail: Philologie und Archäologie im Diskurs; Festschrift für Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert, Vol. 1, edited by Marc Brose et al., 199–238. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Cauville 2007a

- Cauville, Sylvie. 2007a. Le temple de Dendara. Vol. 12, Les parois extérieures du naos. Pt. 1, Textes hiéroglyphiques. Pt. 2, Planches, dessin et photographies. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Cauville 2007b

- Cauville, Sylvie. 2007b. Le temple de Dendara. Vol. 13, Façade et colonnes du pronaos. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. https://www.ifao.egnet.net/uploads/publications/enligne/Temples-Dendara013.pdf.

- Cauville 2011a

- Cauville, Sylvie. 2011a. Dendara XIII: Traduction; Le pronaos du temple d’Hathor; Façade et colonnes. Leuven: Peeters.

- Cauville 2011b

- Cauville, Sylvie. 2011b. Dendara XIV: Traduction; Le pronaos du temple d’Hathor; Parois intérieures. Leuven: Peeters.

- Cooney 2018

- Cooney, Kara. 2018. When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt. Washington, DC: National Geographic.

- Ćwiek 2014

- Ćwiek, Andrzej. 2014. “Old and Middle Kingdom Tradition in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari.” Études et Travaux (Institut des Cultures Méditerranéennes et Orientales de l’Académie Polonaise des Sciences) 27:61–93.

- De Meulenaere 1976

- De Meulenaere, Herman. 1976. “Cults and Priesthoods of the Mendesian Nome.” In Mendes II, edited by Herman De Meulenaere and Pierre MacKay. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

- Demetriou 2010

- Demetriou, Denise. 2010. “Tῆς πάσης ναυτιλίης φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea.” Kernos 23:67–89.

- Dunand 1973

- Dunand, Françoise. 1973. Le culte d’Isis dans le bassin oriental de la Méditerranée. Vol. 1, Le culte d’Isis et les Ptolémées. Leiden: Brill.

- Dunham 1957

- Dunham, Dows. 1957. The Royal Cemeteries of Kush. Vol. 4, Royal Tombs at Meroë and Barkal. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Ebling 2018

- Ebling, Florian. 2018. “Editorial Note: Jan Assmann’s Transformation of Reception Studies to Cultural History.” In Mnemohistory and Cultural Memory: Essays in Honour of Jan Assmann, edited by Florian Ebling, 5–8. Heidelberg: Propylaeum.

- Eckert 2016

- Eckert, Martin. 2016. Die Aphrodite der Seefahrer und ihre Heiligtümer am Mittelmeer: Archäologische Untersuchungen zu interkulturellen Kontaktzonen am Mittelmeer in der späten Bronzezeit und frühen Eisenzeit. Berlin: LIT.

- El-Masry, Altenmüller, and Thissen 2012

- El-Masry, Yahia, Hartwig Altenmüller, and Heinz-Josef Thissen. 2012. Das Synodaldekret von Alexandria aus dem Jahre 243 v. Chr. Hamburg: Buske.

- Eldamaty 2011

- Eldamaty, Mamdouh. 2011. “Die ptolemäische Königin als weiblicher Horus.” In Ägypten zwischen innerem Zwist und äußerem Druck: Die Zeit Ptolemaios’ VI. bis VIII., edited by Andrea Jördens and Joachim Friedrich Quack, 24–57. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Etman 2003

- Etman, Ahmed. 2003. “Cleopatra VII as Nea Isis: A Mediterranean Identity.” In Faraoni come dei, Tolemei come faraoni, edited by Nicola Bonacasa et al., 75–78. Turin: Museo Egizio.

- Fauerbach 2018

- Fauerbach, Ulrike. 2018. Der große Pylon des Horus-Tempels von Edfu: Architektur und Bautechnik eines monumentalen Torbaus der Ptolemaierzeit. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Fraser 1972

- Fraser, Peter Marshall. 1972. Ptolemaic Alexandria. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Gabolde 1992

- Gabolde, Marc. 1992. “Étude sur l’évolution des dénominations et de l’aspect des pylônes du temple d’Amon-Rê à Karnak.” Bulletin de Cercle Lyonnais d’Égyptologie Victor Loret 6:17–60.

- Gabolde and Laisney 2017

- Gabolde, Luc, and Damien Laisney. 2017. “L’orientation du temple d’Héliopolis: Données géophysiques et implications historiques.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 73:105–32.

- Gauthier 1911

- Gauthier, Henri. 1911. Le temple de Kalabchah. Vol. 1, Texte. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Gill 2015

- Gill, Ann-Katrin. 2015. “The Spells against Enemies in the Papyrus of Pawerem (P. BM EA 10252): A Preliminary Report.” In Liturgical Texts for Osiris and the Deceased in Late Period and Greco-Roman Egypt, edited by Burkhard Backes and Jacco Dieleman, 133–42. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Gill 2019

- Gill, Ann-Katrin. 2019. The Hieratic Ritual Books of Pawerem (P. BM EA 10252 and P. BM EA 10081) from the Late 4th Century BC. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Goebs and Baines 2018

- Goebs, Katja, and John Baines. 2018. “Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth.” Revue de l’histoire des religions 235 (4):645–81.

- Goelet 1991

- Goelet, Ogden. 1991. “The Blessing of Ptah.” In Fragments of a Shattered Visage: The Proceedings of the International Symposium of Ramesses the Great, edited by Edward Bleiberg and Rita E. Freed, 28–37. Memphis: Memphis State University.

- Graefe 1983

- Graefe, Erhart. 1983. “Der ‘Sonnenaufgang zwischen den Pylontürmen’—Erstes Bad, Krönung und Epiphanie des Sonnengottes—à propos Carter, Tutankhamen, Handlist no 181.” Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 14:55–79.

- Griffin 2018

- Griffin, Kenneth. 2018. All the Rḫyt-People Adore: The Role of the Rekhyt-People in Egyptian Religion. London: Golden House.

- Griffith 1937

- Griffith, Francis Llewellyn. 1937. Catalogue of the Demotic Graffiti of the Dodecaschoenus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grimm 1999

- Grimm, Günter. 1999. Alexandria: Die erste Königsstadt der hellenistischen Welt. Mainz: Zabern.

- Gundlach 1995

- Gundlach, Rolf. 1995. “Das Dekorationsprogramm der Tempel von Abu Simbel und ihre kultische und königsideologische Funktion.” In Systeme und Programme der ägyptischen Tempeldekoration, edited by Dieter Kurth, 47–71. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Handler 1971

- Handler, Susan. 1971. “Architecture on the Roman Coins of Alexandria.” American Journal of Archaeology 75:57–74.

- Hauben 1970

- Hauben, Hans. 1970. Callicrates of Samos: A Contribution to the Study of the Ptolemaic Admiralty. Leuven: Peeters.

- Hauben 1983

- Hauben, Hans. 1983. “Arsinoé II et la politique extérieure.” In Egypt and the Hellenistic World, edited by Edmond Van ’t Dack et al., 99–127. Leuven: Peeters.

- Hauben 2013

- Hauben, Hans. 2013. “Callicrates of Samos and Patroclus of Macedon, Champions of Ptolemaic Thalassocracy.” In The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile: Studies in Waterborne Power, edited by Kostas Buraselis, Mary Stefanou, and Dorothy J. Thompson, 39–65. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heinen 2009

- Heinen, Heinz. 2009. “‘Cleopatra regina amica populi Romani et caesaris’: Die Rom- und Caesarenfreundschaft der Kleopatra; Gebrauch und Missbrauch eines politischen Instruments.” In Kleopatra-Studien: Gesammelte Schriften zur ausgehenden Ptolemäerzeit, edited by Heinz Heinen, 288–98. Konstanz: UVK Universitätsverlag.

- Helmbold-Doyé 2019

- Helmbold-Doyé, Jana. 2019. “Tomb Architecture and Burial Customs of the Elite during the Meroitic Phase in the Kingdom of Kush.” In Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by Dietrich Raue, 2:783–809. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Hinkel 1981

- Hinkel, Friedrich W. 1981. “Die Größe der Meroitischen Pyramiden.” In Studies in Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Sudan: Essays in Honor of Dow Dunham on the Occasion of His 90th Birthday, June 1, 1980, edited by William Kelly Simpson and Whitney Davis, 91–98. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Hinkel 1996

- Hinkel, Friedrich W. 1996. “Meroitische Architektur.” In Sudan: Antike Königreiche am Nil, edited by Dietrich Wildung, 391–415. Tübingen: Wasmuth.

- Hinkel 2000

- Hinkel, Friedrich W. 2000. “The Royal Pyramids of Meroe: Architecture, Construction and Reconstruction of a Sacred Landscape.” Sudan and Nubia 4:11–27.

- Hinkel and Yellin 1998

- Hinkel, Friedrich W., and Janice W. Yellin. 1998. “Royal Pyramid Chapels of Kush Project.” In Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995, edited by Christopher Eyre, 555–62. Leuven: Peeters.

- Hoffmann 2015

- Hoffmann, Friedhelm. 2015. “Königinnen in ägyptischen Quellen der römischen Zeit.” In Ägyptische Königinnen vom Neuen Reich bis in die islamische Zeit, edited by Mamdouh Eldamaty at al., 139–56. Vaterstetten: Brose.

- Hölbl 2001

- Hölbl, Günter. 2001. A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. London: Routledge.

- Hölbl 2003

- Hölbl, Günter. 2003. “Ptolemäische Königin und weiblicher Pharao.” In Faraoni come dei, Tolemei come faraoni, edited by Nicola Bonacasa et al., 88–97. Turin: Museo Egizio.

- Kákosy 1994

- Kákosy, László. 1994. “Tempel und Mysterien.” In Ägyptische Tempel—Struktur, Funktion und Programm: Akten der ägyptologischen Tempeltagung in Gosen 1990 und in Mainz 1992, edited by Rolf Gundlach and Matthias Rochholz, 165–73. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg.

- Larché 2018

- Larché, François. 2018. “Nouvelles données et interprétation des vestiges du temple de Sésostris Ier à Tôd.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture 3:100–139.

- Leitz 2002

- Leitz, Christian, ed. 2002. Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. 7 vols. Leuven: Peeters.

- Lohwasser 1994

- Lohwasser, Angelika. 1994. “Die Königin Amanishakheto.” Der Antike Sudan: Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin 1:30–31.

- Lohwasser 2001

- Lohwasser, Angelika. 2001. “Der ‘Thronschatz’ der Königin Amanishakheto.” In Begegnungen: Antike Kulturen im Niltal; Festgabe für Erika Endesfelder, Karl-Heinz Priese, Walter Friedrich Reinecke, Steffen Wenig, edited by Caris-Beatrice Arnst, Ingelore Hafemann, and Angelika Lohwasser, 285–302. Leipzig: Wodtke & Stegbauer.

- Lohwasser 2004

- Lohwasser, Angelika. 2004. “Pyramiden in Nubien.” In Die Pyramiden Ägyptens: Monumente der Ewigkeit, edited by Christian Hölzl, 207–14. Vienna: Brandstätter.

- Lohwasser 2021

- Lohwasser, Angelika. 2021. “The Role and Status of Royal Women in Kush.” In The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World, edited by Elizabeth D. Carney and Sabine Müller, 61–72. Abington, UK: Routledge.

- Łukaszewicz 2016

- Łukaszewicz, Adam. 2016. “Cleopatra and Kandake.” In Aegyptus et Nubia christiana: The Włodzimierz Godlewski Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday, edited by Adam Łajtar, Artur Obłuski, and Iwona Zych, 691–98. Warsaw: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology.

- Malaise 2005

- Malaise, Michel. 2005. Pour une terminologie et une analyse des cultes isiaques. Brussels: Classe des Lettres, Académie Royale de Belgique.

- Martzolff 2012

- Martzolff, Laetitia. 2012. “Les mâts d’ornement des pylônes aux époques ptolémaïque et romaine: Entre réalité et idéal.” Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 139 (2): 145–57.

- McKenzie 2007

- McKenzie, Judith. 2007. The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 BC to AD 700. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Megahed and Vymazalová 2011

- Megahed, Mohamed, and Hana Vymazalová. 2011. “Ancient Egyptian Royal Circumcision from the Pyramid Complex of Djedkare.” Anthropologie 49:155–64.

- Megahed and Vymazalová 2015

- Megahed, Mohamed, and Hana Vymazalová. 2015. “The South-Saqqara Circumcision Scene: A Fragment of an Old Kingdom Birth-Legend.” In Royal versus Divine Authority: Acquisition, Legitimization and Renewal of Power, edited by Filip Coppens, Jiří Janák, and Hana Vymazalová, 275–87. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Merkelbach 1995

- Merkelbach, Reinhold. 1995. Isis Regina—Zeus Serapis. Stuttgart: Teubner.

- Minas-Nerpel 2014

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina. 2014. “Koregentschaft und Thronfolge: Legitimation ptolemäischer Machtstrukturen in den ägyptischen Tempeln der Ptolemäerzeit.” In Orient und Okzident in hellenistischer Zeit, edited by Friedhelm Hoffmann and Karin Stella Schmidt, 143–66. Vaterstetten: Brose.

- Minas-Nerpel 2019a

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina. 2019a. “Ptolemaic Queens as Ritualists and Recipients of Cults: The Cases of Arsinoe II and Berenike II.” Ancient Society 49:141–83.

- Minas-Nerpel 2019b

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina. 2019b. “‘Seeing Double’: Intercultural Dimensions of the Royal Ideology in Ptolemaic Egypt.” In Egyptian Royal Ideology and Kingship under Periods of Foreign Rulers: Case Studies from the First Millennium BC, edited by Julia Budka, 189–205. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Minas-Nerpel 2021

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina. 2021. “Regnant Women in Egypt.” In The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean, edited by Elizabeth D. Carney and Sabine Müller, 22–34. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Minas-Nerpel and Preys forthcoming

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina, and René Preys. Forthcoming. The Kiosk of Taharqa. Vol. II: The Ptolemaic Decoration (TahKiosk nos. E1–24, F1–4), Travaux du Centre Franco-égyptien d’Etude des Temples de Karnak. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Müller 2009

- Müller, Sabine. 2009. Das hellenistische Königspaar in der medialen Repräsentation: Ptolemaios II. und Arsinoe II. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Nagel 2014

- Nagel, Svenja. 2014. “Isis und die Herrscher: Eine ägyptische Göttin als (Über-)Trägerin von Macht und Herrschaft für Pharaonen, Ptolemäer und Kaiser.” In Macht und Ohnmacht: Religiöse, soziale und ökonomische Spannungsfelder in frühen Gesellschaften, edited by Diamantis Panagiotopoulos and Maren Schentuleit, 115–45. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Nagel 2019

- Nagel, Svenja. 2019. Isis im Römischen Reich. Vol. 1, Die Göttin im griechisch-römischen Ägypten. Vol. 2, Adaption(en) des Kultes im Westen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Naster 1968

- Naster, Paul. 1968. “Le pylône égyptien sur les monnaies impériales d’Alexandrie.” In Antidorum W. Peremans sexagenario ab alumnis oblatum, edited by Willy Peremans and Albert Torhoudt, 181–90. Leuven: Peeters.

- Nisetich 2005

- Nisetich, Frank, trans. 2005. “The Poems of Posidippus.” In The New Posidippus: A Hellenistic Poetry Book, edited by Kathryn Gutzwiller, 17–64. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oppenheim 2011

- Oppenheim, Adela. 2011. “The Early Life of Pharaoh: Divine Birth and Adolescence Scenes in the Causeway of Senwosret III at Dahshur.” In Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010, edited by Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, and Jaromir Krejci, 1:171–88. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University.

- Payraudeau 2015

- Payraudeau, Frédéric. 2015. “Considérations sur quelques titres des reines de l’Ancien Empire à l’époque ptolémaïque.” In Cinquante ans d’éternité: Jubilé de la Mission archéologique française de Saqqâra (1963–2013), edited by Rémi Legros, 209–25. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Petrie 1901

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1901. The Royal Tombs of the Earliest Dynasties. Vol. 2. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

- Pfeiffer 2017

- Pfeiffer, Stefan. 2017. Die Ptolemäer: Im Reich der Kleopatra. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Pfeiffer 2021

- Pfeiffer, Stefan. 2021. “Royal Women and Ptolemaic Cults.” In The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World, edited by Elizabeth D. Carney and Sabine Müller, 96–107. Abington, UK: Routledge.

- Pfrommer 2002

- Pfrommer, Michael. 2002. Königinnen vom Nil. Mainz: Zabern.

- Plantzos 2011

- Plantzos, Dimitris. 2011. “The Iconography of Assimilation: Isis and the Royal Imagery of Ptolemaic Seal Impressions.” In More than Men, Less than Gods: Studies on Royal Cult and Imperial Worship, edited by Panagiotos P. Iossif, 389–415. Leuven: Peeters.

- Pomeroy 1991

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. 1991. Women’s History and Ancient History. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Pope 2008–9

- Pope, Jeremy. 2008–9. “The Demotic Proskynema of a Meroitic Envoy to Roman Egypt (Philae 416).” Enchoria 31:68–103.

- Porter and Moss 1972

- Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind L. B. Moss. 1972. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings. Vol. 2, Theban Temples. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Preys 2002a

- Preys, René. 2002a. “Hathor au sceptre-ouas: Images et textes au service de la théologie.” Revue d’Égyptologie 53:197–212.

- Preys 2002b

- Preys, René. 2002b. “Isis et Hathor nbtyt rḫyt.” Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 102:327–51.

- Preys 2015