1. From Thutmose III to Homer to Blackadder: Egypt, the Aegean, and the “Barbarian Periphery” of the Late Bronze Age World System

- Jorrit M. Kelder

Associate of the Sub-Faculty of Near and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford; Senior Grant Adviser, Leiden University

Although numerous studies have focused on various aspects of Late Bronze Age interconnections (such as the exchange of objects, raw materials, animals and plants, specialist craftsmen, artists, and even diplomatic marriages), the role of the military in the exchange of technologies and ideas has remained remarkably understudied. By highlighting a number of artifacts that have been found throughout the eastern Mediterranean, this paper seeks to explore the role of the military and especially mercenaries as a conduit of knowledge and ideas in the Late Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean and beyond.

A Stone Mace-Head in the Age of Bronze

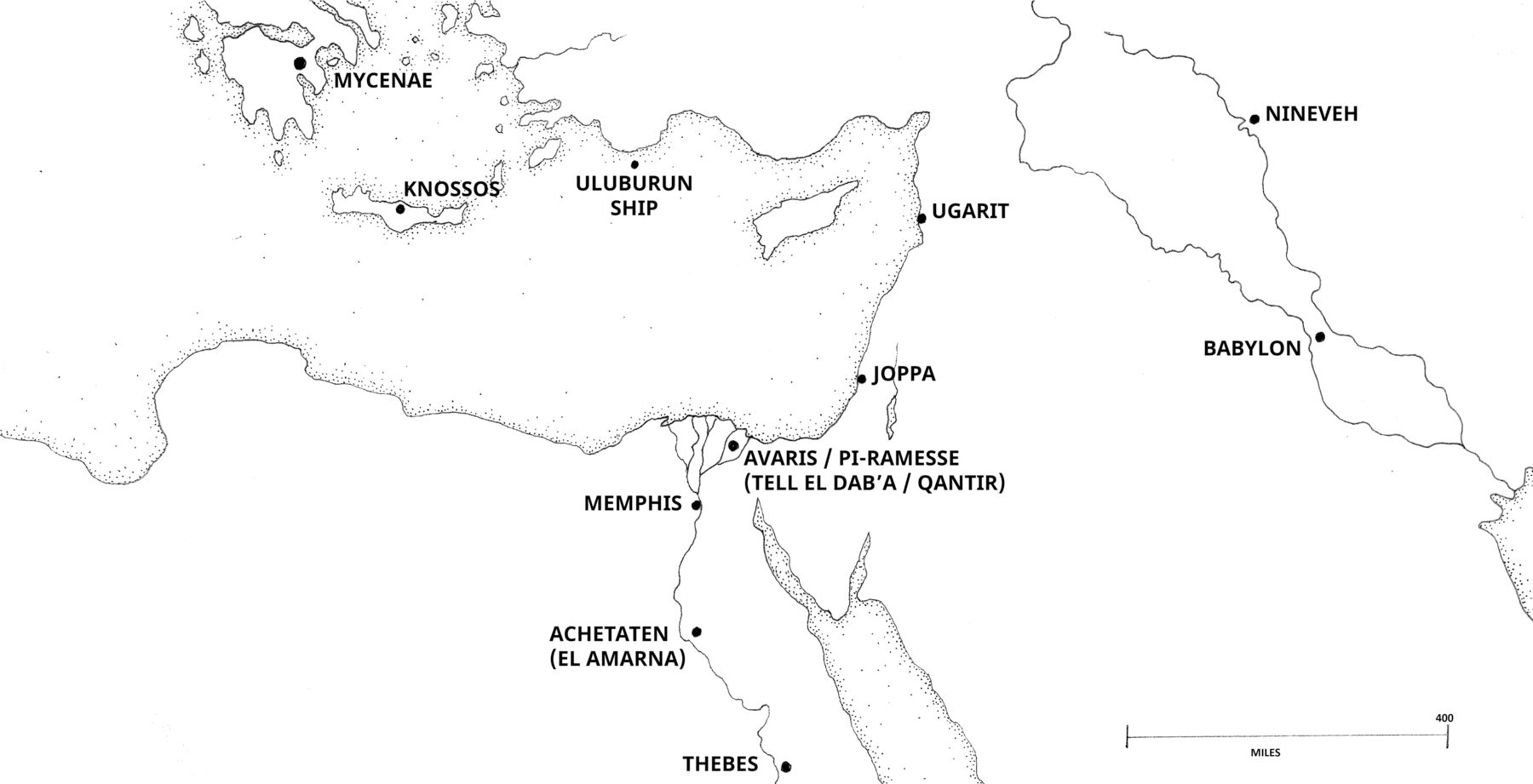

Few sites illustrate the close Bronze Age relations between the Aegean, Cyprus, the Levant, and Egypt as well as the Uluburun shipwreck.1 The ship, measuring approximately twenty meters, was probably of Levantine build and on its way to the north when it sank soon after 1305 BC (if the dendrochronological data may be believed).2 Its cargo was preserved at the bottom of the Gulf of Antalya (south of present-day Antalya Province, Turkey), providing a unique insight into the complexity of Late Bronze Age long-distance exchange and the sheer scale and variety of objects and materials that were transported (fig. 1.1). Apart from a whopping ten tons in copper oxhide, bun-shaped and oval ingots, the ship carried Canaanite vessels (containing pistacia resin among other things), glass ingots of uncertain (possibly Egyptian) origin, ebony and ivory, silver and gold jewelry from Egypt and the Levant, and a smaller group of objects that came from the Aegean world, including eighteen stirrup jars and a flask, two Mycenaean-type swords, razors, and two glass relief plaques, which are thought to have been part of two pectorals. Cemal Pulak, the excavator of the wreck, has proposed that these Aegean objects were the personal effects of two high-ranking Mycenaeans, who may have been acting as emissaries of a Mycenaean king.3 Although this interpretation must remain conjecture, the cargo of the ship does indeed resemble many of the items that are listed in the Amarna Letters as part of diplomatic gift exchanges.4

What may lend further credibility to Pulak’s suggestion is the presence of a remarkable diptych. The materials of this folded writing board—choice boxwood and ivory—suggest that it was not a mere trader’s log but rather a diplomatic passport, perhaps including a list of the gifts that were to be presented at court (like those we know from the Amarna archive).5 This does not necessarily require its bearer to be a Mycenaean, although Martien Dillo has observed that the signs engraved on the diptych’s edges seem to represent Mycenaean numerals.6 It thus seems reasonable to assume, with Pulak, that the Uluburun ship was indeed laden with diplomatic gifts destined for one of the palatial centers in the Mycenaean world and that at least two of its passengers were Mycenaean diplomats, escorting their precious cargo.

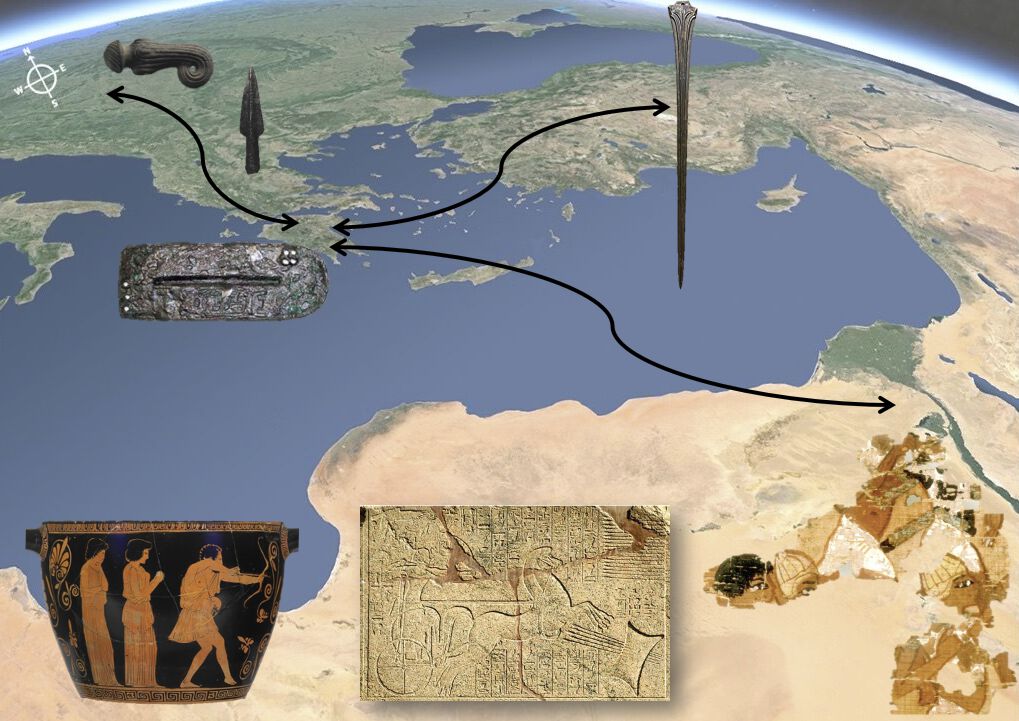

The voyage to and from the Levant (or even further south, to Egypt) was not without its risks, as indeed is demonstrated by the very fact that the Uluburun ship sank. But apart from bad weather, human factors could also imperil the Late Bronze Age traveler. There is ample evidence for this in contemporary texts, in which there are references to rulers detaining foreign diplomats, trade embargoes prohibiting ships from entering port (such as the so-called Sausgamuwa Treaty), and—more frequently—piracy.7 The messengers on board the Uluburun ship may have prepared for such eventualities. Both appear to have carried swords, and they may have even had their own escort. These Mycenaeans were not the only conspicuous people on board. Pulak has suggested that a remarkable stone mace-head of a type known from the Carpathian-Pontic region found in the Uluburun wreck may have belonged to a—clearly important—northerner (fig. 1.2).8 Several other objects—including a particular type of dress pin, a bronze sword with central Mediterranean (but also Balkan) parallels, and various spearheads of a type that was common in Macedonia—may also have belonged to this person (or perhaps even several “northerners”).9 In view of the quantity of weapons, it is unlikely that this “northerner” was a merchant or envoy himself; instead he may have been on board as a member of the Mycenaeans’ cortege. Heavily armed, he could have served as their bodyguard, although the presence of the mace-head may point toward a more ceremonial task as “mace-bearer”—announcing the arrival of, and instilling awe for, his Mycenaean companions (in the manner of Amirullah the mace-bearer, employed by Josiah Harlan on his voyages through Afghanistan in the nineteenth century).10

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2Mercenaries from the Edge of the World?

Could the “mace-bearer” have been a mercenary from the edges of the Mycenaean palatial world? Although the Bronze Age in the Balkans to a large extent remains an archaeological terra incognita, recent research suggests that the regions to the north of Greece—Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, and especially the Carpathian basin—were involved in the Mediterranean world to a far greater extent than has hitherto been thought. Though the precise nature of the area’s relations with the Mycenaean world remains unclear, one can be reasonably sure that Mycenaean demand for metals played an important role in these connections. The Carpathians were rich in gold, silver, and copper, and there is good evidence for extensive mining and metalworking (and related lead pollution) in the region during the Late Bronze Age and, indeed, even before that.11 In exchange for metals and finished objects (for the skills of the Carpathian smiths were considerable), as well as objects and materials from regions further to the north, such as amber, Aegean traders provided their Carpathian neighbors with materials and objects from the Mediterranean, the Near East, and beyond.12 In such a context of relatively close connections between the Mycenaean world and its northern neighbors, it is plausible to assume that Mycenaean elites employed foreign mercenaries from the Balkans.13 The fact that a significant portion of the Mycenaean imports (or possible local imitations of them) in southern Bulgaria consist of swords and spearheads may further support such a scenario.14

The Mycenaeans would not have been alone in their practice of employing foreigners in their army, for the tradition was already well established throughout the Near East by the fourteenth century BC. There, too, mercenaries typically came from the “periphery”—regions that were perceived as uncivilized and dangerous—and it is precisely for those qualities that their inhabitants made such good soldiers. One of the earliest references to the recruitment of mercenaries is a text from the reign of Zimri-Lim (ca. 1779–1761 BC), king of the powerful city-state of Mari (in northern Mesopotamia), who recruited five thousand soldiers from the Hana, a generic term for nomads. These bedouin were clearly preferable as soldiers to the “civilized” people of Mari itself, as contemporary texts emphasize their qualities as soldiers and their capacity to deal with wild animals such as lions.15

Egypt, too, had a long tradition of incorporating foreign specialists into its army. There, though, they appear to have been drawn mostly from conquered people, from territories that fell under pharaonic control. The best-known example for this practice is the inclusion of Nubian archers in the Egyptian army. But other specialist corps, such as the Medjay, were similarly relied on.16 By the time of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1069 BC), Egyptian texts mention other foreigners in the Egyptian army, including Libyans, Canaanites, and Sherden—the last known mostly from texts dating to the end of the Bronze Age, in which they are part of the invading “Sea Peoples,” a collection of various peoples whose origins are still unclear but who seem to have coalesced, at least occasionally, into larger seaborne raiding parties. It remains unclear how most of these foreigners entered the Egyptian army, though in the case of the Sherden the texts indicate that they were forced into service following their defeat at the hands of the Egyptians.

Faith and Technology

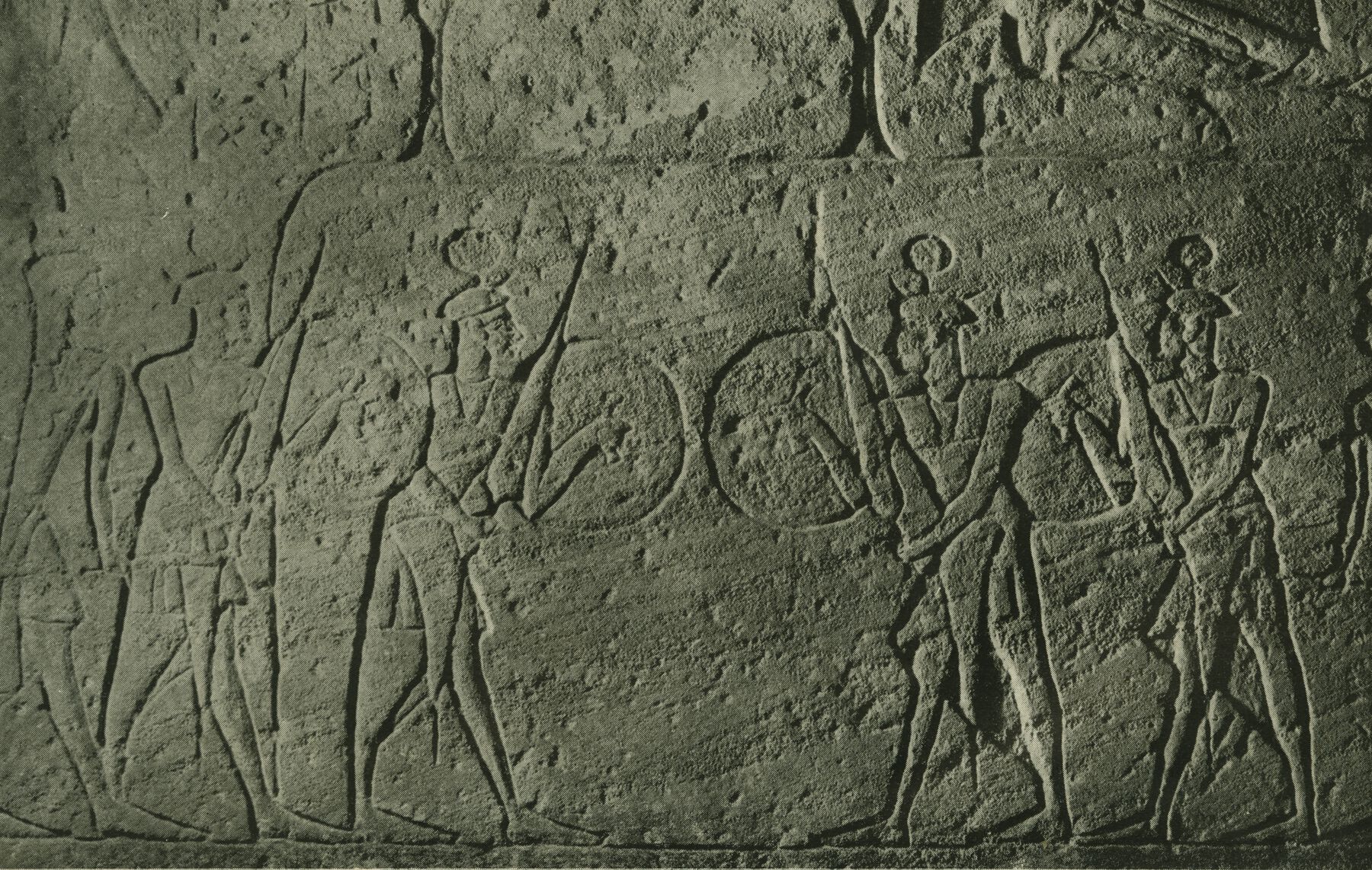

The Sherden are of particular interest as an example of how mercenaries served as a conduit for the introduction of military technologies. Though they are probably first mentioned in a letter in the Amarna archive (EA 122) from Rib-hadda, mayor of Gubla (Byblos), as še-er-ta-an-nu, they appear in Egyptian iconography only during the reign of Ramesses II, half a century or so later. They are shown wearing a distinctive type of horned helmet with a curious globular crest on top and carrying a circular shield with multiple (metal?) bosses while wielding a sword of an uncertain, though definitely un-Egyptian type, perhaps related to the Naue II sword, which originated in Europe in the fifteenth century BC. The Sherden ships were unlike anything the Egyptians had seen before. Like the “northerner” on the Uluburun ship, the Sherden were, after their defeat and incorporation into the Egyptian army, valued as bodyguards and accompanied Ramesses II at the Battle of Kadesh (fig. 1.3).17

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.3Although the precise terms of their employment in Egypt are unknown, it is clear that many Sherden never left the land of the Nile. Instead they settled there, acquired land (presumably in payment for their military service), and Egyptianized to a remarkable extent. Nevertheless, there is evidence that they retained some of their own cultural characteristics and—a century after their first appearance in Egypt, early in the reign of Ramesses II—still stood out from the Egyptians. Papyri from the reigns of Ramesses V (the Wilbour Papyrus) and Ramesses IX (the Adoption Papyrus) still identify Sherden among the Egyptian population, in particular at the site of Gurob.18 There is some archaeological evidence to support this. W. M. Flinders Petrie, during his excavations at Gurob, was struck by the quantity of imports at the site, especially Mycenaean pottery, as well a number of peculiar features, notably various groups of burnt objects, which, he suggested, might indicate Aegean cremation customs.19 This suggestion has recently been questioned,20 and Petrie’s so-called Burnt Groups may be more plausibly identified as the remains of looted graves, probably dating to the Third Intermediate Period (the burning may be explained as a crude attempt by the looters to extract any metal). Although Petrie’s argument for a Mycenaean tradition of cremation at Gurob thus seems questionable, various other finds at Gurob do suggest a foreign presence at the site. They include the occurrence of non-Egyptian names on coffins, including a certain Anen-Tursha, who, despite his name, seems to have risen to prominence in the pharaonic administration, eventually attaining the position of deputy overseer of the royal harem.

Most significant and spectacular is a wooden ship-cart model (fig. 1.4a–b).21 Petrie, when he discovered the remains of this model, assumed that it represented an Egyptian barge. A recent study by Shelley Wachsmann has now shown this to be wrong; instead, he notes, it “represents a land-based cultic ship (cart) that had been patterned after an actual ship, in this case a pentakonter. Put simply, the Gurob model is a copy of a copy. And while the Gurob model was thus twice removed from the original war galley that served as its prototype, the information that the model supplies regarding the transfer of cult in the seam between the Late Bronze and Iron Ages cannot be overemphasized.”22 The ship, then, is a remarkable example of religious syncretism, for while in Egypt models of barges are known from religious processions, in which they were usually carried on long poles by priests, the example from Gurob is a novel, foreign type of ship that—in Egypt at least—was clearly associated with the Sea Peoples, in particular the Sherden. As such, the Gurob ship model not only serves as an example of religious syncretism but also demonstrates the role of foreigners in the transfer of military naval technology.

Figure 1.4a

Figure 1.4a Figure 1.4b

Figure 1.4bIn a series of important publications, Jeffrey Emanuel has demonstrated the importance of the Sea Peoples as a catalyst for maritime innovation.23 While various novel features, such as the loose-footed, brailed sail and the top-mounted crow’s nest, were already known in the Levant from the fourteenth century BC onward, it appears that their full military potential, especially in combination with the new (Aegean?) type of war galley, like that represented by the ship model from Gurob, was first realized by groups such as the Sherden. It was only after encountering the first groups of Sea Peoples early in the reign of Ramesses II that Egyptian shipwrights took notice of the value of innovations and started implementing them in their own designs. The change can be traced, as Emanuel has shown, in various Egyptian reliefs of the 19th Dynasty. While Egyptian ships at the time of Ramesses II’s first encounters with the Sherden were typically Egyptian, those that were deployed by Ramesses III (as shown on the walls of his temple at Medinet Habu), although still based on Egyptian riverine ships rather than the Aegean galley, are otherwise remarkably similar to the ships of their foes, with a top-mounted crow’s nest and a loose-footed, brailed sail. Thus the arrival in Egypt of the Sea Peoples—despite the havoc they wrought—is also associated with a number of remarkable breakthroughs in ship design that, in many ways, influenced the shipbuilding traditions in Greece and Phoenicia in the millennium to come.24

Traveling Soldiers, Traveling Tales

It seems reasonable to assume that mercenaries were important agents in the transfer of military technology, tying the peripheries of the ancient world to the centers of urban societies. This process of transfer, however, extended both ways. Plate armor appeared in temperate Europe during the thirteenth century BC, at around the same time that the Naue II sword came to Greece.25 It is quite likely that other, less tangible or archaeologically demonstrable know-how traveled with these new types of weapons, including, as N. K. Sandars has suggested,26 foreign combat tactics, but one may also think of popular stories of love and war, the type of stories that would have been recited or sung around a traveler’s or military campfire. Indeed, the “northern mercenary” on board the Uluburun ship may have been one of those who brought new ideas from the Balkans to the Aegean.

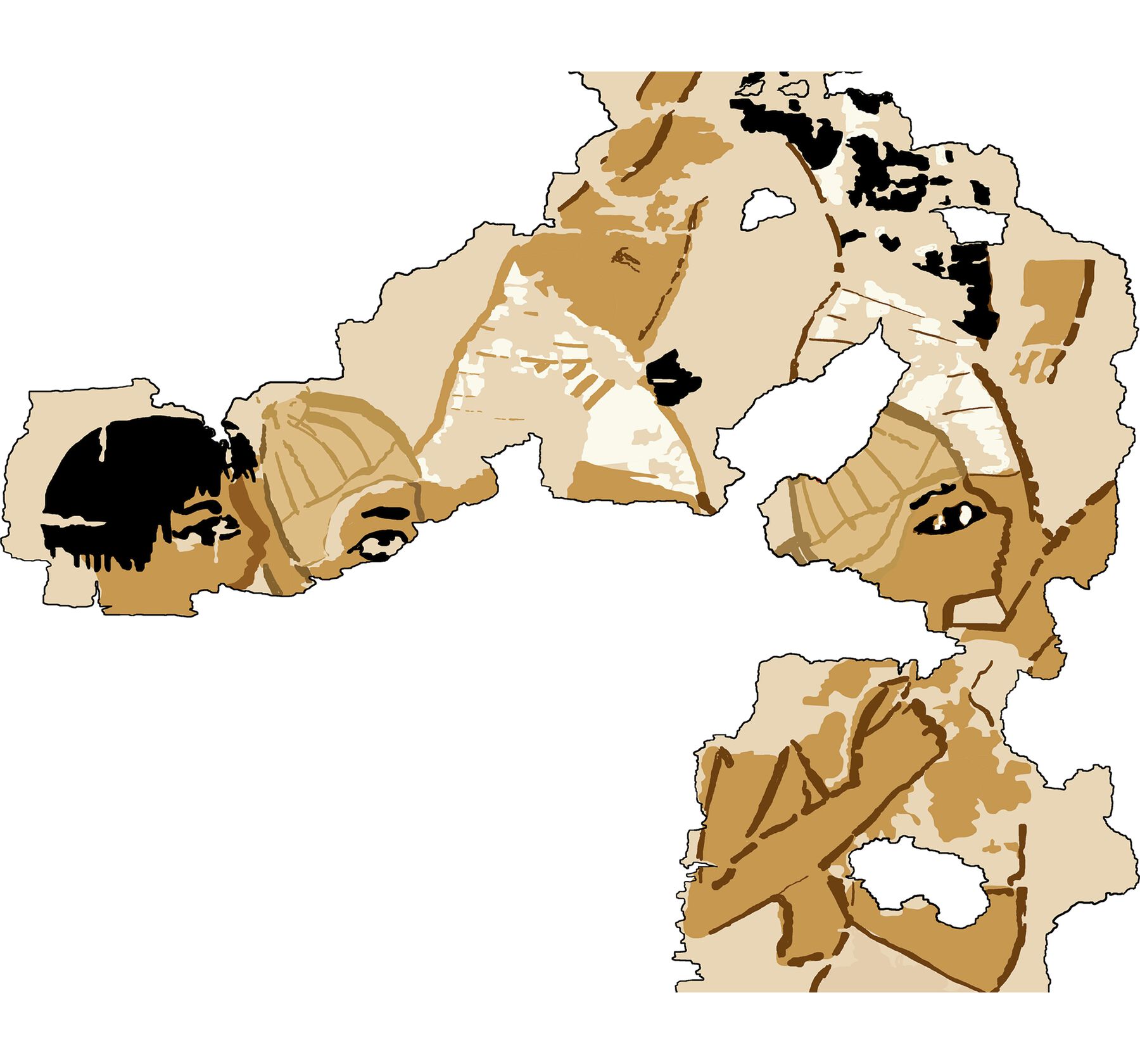

Mycenaean Greece was dotted with palatial centers that were home to a literate elite. From Hittite texts, we know that Mycenaean rulers were involved in high-level diplomacy, participated in royal gift exchange, and personally knew highborn Hittite officers and probably even Hittite royalty.27 Tawagalawa/Ete(w)okle(we)s, the brother of the king of Ahhiyawa, for example, reportedly rode together with the personal charioteer of the Hittite king. The Mycenaeans themselves may have served as foreign mercenaries.28 A sword that was captured during a Hittite campaign against the Assuwa League of western Anatolia, for example, is of a clearly Aegean-inspired type (even though its dedicatory inscription indicates that it was used by a soldier of, and probably forged in, Assuwa29), and two texts from the Hittite vassal state of Ugarit suggest that, at least toward the end of the Bronze Age, the Hittites may have employed soldiers from the Mycenaean world (although the exact identification of the men from Hiyawa and the nature of the PAD.MEŠ [metal supplies, payment, foodstuff?] they are expecting, is debated).30 Similarly, there are indications that Mycenaeans served in the Egyptian pharaoh’s armies from at least the Amarna period onward. The famous pictorial papyrus found at Akhetaten (Tell el-Amarna) offers a rare glimpse of these Aegeans, who wear boar’s-tusk helmets but are otherwise dressed like Egyptians (fig. 1.5a–b).31

Figure 1.5a

Figure 1.5a Figure 1.5b

Figure 1.5bArchaeology offers some additional evidence in the form of a piece of just such a boar’s-tusk helmet that was found at Pi-Ramesse, in the Nile Delta.32 The Gurob ship model, moreover, may similarly hint at a Mycenaean presence, for even though the origins of the Sherden remain murky, the ship they used is clearly Aegean-inspired. In fact, its black and red paint is so idiosyncratic that both Wachsmann and Emanuel pointed out the similarity to the ships of the Achaeans in Homer’s Iliad. Emanuel writes: “This preserved polychromatic schema not only makes the model unique among known representations of Helladic ships, but it aligns with—and helps us visually understand—both Homer’s description of the Achaeans’ ships as μέλας ‘black,’ his reference to Odysseus’ ships specifically as μιλτοπάρῃος ‘red-cheeked.’ Odysseus’ ships are also referred to as φοινικοπάρῃος ‘purple-cheeked,’ but most noteworthy is the fact that only Odysseus’ ships are identified by the ‘red-’ and ‘purple-cheeked’ epithets.”33 It is likely that, like Odysseus, at least some of these Mycenaean mercenaries entered Egyptian service voluntarily or, at the very least, were able to leave Egypt after their period of service ended. A piece of scale armor of a type worn by Near Eastern charioteers, stamped with the cartouche of Ramesses II—a rare find on the island of Salamis, off the coast of Athens—may have belonged to one of these returning soldiers.34

There can be no doubt that these returning warriors were held in high regard and had a special status in their communities. Apart from bringing souvenirs such as scale armor with them, they doubtless told stories about their experiences in distant lands. These stories, of course, were embellished with fantastic elements, hearsay, and pure fantasy that served as a conduit for literary topoi. The remarkable parallel between the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep II, who showed off his military prowess by shooting arrows through a copper ingot, and Odysseus’s ability to shoot an arrow through a row of twelve ax-heads, may be understood through the prism of such storytelling, whereby an original Egyptian story was transferred to Greek epic.35 Odysseus, in particular, seems to have had quite a few Egyptian-inspired tricks up his sleeve. Apart from his abilities with his bow, his famous trick with the Trojan horse is remarkably similar to the Egyptian story of the general Djehuty, who served under Thutmose III and is reported to have captured the enemy city of Joppa by concealing his soldiers in large baskets offered to the ruler of the city as tribute.36

Not all of these literary elements need to have come to Greece via returning mercenaries, of course, though it would make sense for precisely this type of adventurer to be familiar with heroic stories—having learned them, perhaps, from foreign comrades at the campfire—and to integrate them into their own songs of glory and fame. The similarities between Near Eastern stories about Gilgamesh, Djehuty, Amenhotep II, the Greek epic cycle, and—eventually—northern European epics, such as the song of Beowulf, can be seen in the context of these Late Bronze Age military connections (see fig. 1.6). Elements of these shared topoi (perhaps even some sort of shared warrior ethos) are preserved even in contemporary culture. As such, we may perhaps be forgiven in considering Baldrick’s catchphrase in the BBC television series Blackadder, “My Lord, I have a cunning plan,” as a late twentieth-century (AD) reflection of a story that originated in early fourteenth-century (BC) Egypt and entered European lore through the Greek and Roman epic cycle.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Aaron Burke and Barry Molloy for their feedback and stimulating discussions on ancient mercenaries and ancient technology transfer between the Mycenaean world and the Balkans, and to Luigi Prada for his feedback regarding the Egyptian evidence presented here. I would also like to thank the organizers of the symposium “Egypt, Greece, Rome: Cross-Cultural Encounters in Antiquity”—Jeffrey Spier, Sara E. Cole, and Timothy Potts—for their invitation to present this paper. All views presented here are, of course, my own. I am grateful to Grace Tsai of the Institute for Nautical Archaeology for her assistance in obtaining an image of the mace-head from the Uluburun shipwreck.

Notes

See ; C. Pulak in , 372–73, no. 237; C. Pulak in , 374–75, no. 238a, b. ↩︎

, 214, based on , 782; but see , 2535, for some caution regarding the reliability of this date. ↩︎

C. Pulak in , 374–75, no. 238a, b. reanalyzed and critiqued Pulak’s identification of “Mycenaeans” on board the ship. While Bachhuber (, 353) does indeed note that “we must tread carefully when discussing the personnel on board of the ship,” he also noted that “the pairing of several of the object-types of Aegean manufacture and the observation that many of the object types had not been identified beyond the Aegean prior to the ship’s excavation . . . is enough, for the purposes of this discussion, to suggest that individuals with greater affinity to the Aegean area (as opposed to the Near East or Egypt), may have owned the objects, and so I refer here to them as ‘individuals of possible Aegean origin.’” In the end, much remains a question of weighing probabilities when it comes to reconstructing the ancient world: in this particular case, I feel that all the available evidence supports Pulak’s (and my own) identification of the passengers on board the ship, whereas alternative explanations require much more (circumstantial or special) pleading. ↩︎

For example, letters EA 33 and 34, from the King of Cyprus, and letter EA 14, which includes an inventory of Egyptian gifts. ↩︎

, 3–5. ↩︎

Reported in . ↩︎

For example, Amarna letter EA 38, which refers to raids on Cypriot towns. ↩︎

C. Pulak in , 372–73, no. 237. ↩︎

I owe this suggestion, and the identification of at least six spearheads as of “northern” type, to Barry Molloy (personal communication, August 2, 2018). ↩︎

C. Pulak in , 374–75, no. 238a, b; for Harlan, see . ↩︎

For evidence of early lead pollution, see , with further references. See , 204–10 (esp. 210, with further references), for an overview of the available evidence for metal mining and metalworking. ↩︎

The trade route connecting the ancient Near East with northern Europe may be reconstructed on the basis of glass beads, produced in Mesopotamia and Egypt, throughout these regions. The Mycenaean world appears to have functioned as the nexus of a European and Mediterranean network. See, most recently, and . The distribution of Late Bronze Age swords in Europe (as proposed by ) appears remarkably similar, suggesting close connections between three distinct regions (southern Sweden / northern Denmark, the Carpathians, and the Aegean; see ), whereas the distribution of amber almost exactly matches the “glass-map” (see , 89–90, with further references, for an overview of the distribution of amber). ↩︎

There may even be some linguistic evidence for military interaction between the Mycenaean world and the people living north of it. The Greek term lawagetas, though it does not survive the collapse of the Bronze Age in Greece itself, did survive into the Iron Age in Phrygian, as one of the titles of King Midas. Unlike the title wanax, for instance, which did survive as a royal and divine title in Homer, lawagetas cannot have been borrowed by the Phrygians from the Greeks in post-Mycenaean times. As a result, one must assume that it is a Phrygian cognate of the Mycenaean title (see ) or, more likely, that the Phrygians adopted this term in Mycenaean palatial times, that is, before around 1200 BC (see also , 8). It is significant that this Mycenaean title, with its overtly military connotations (in Linear B, the title is thought to designate a local prince, as noted in , or military commander; its literal meaning is “leader of the armed men”), survived in Phrygian. ↩︎

See ; , 128. See , 217–23, and (esp. 242, maps 1 and 2) for an overview of the available evidence. ↩︎

, 29; , 121. ↩︎

Originally a generic Egyptian term to designate groups in the Lower Nubian eastern desert, the term Medjay by the Middle Kingdom may have been adopted by some of these groups, whose members were drafted into the military to patrol the desert routes; see . ↩︎

For an overview of their role in the military, see . ↩︎

The Wilbour Papyrus is now in the Brooklyn Museum, 34.5596.4, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/152121; Trismegistos no. 113892, https://www.trismegistos.org/text/113892; see also . For the Adoption Papyrus, see . ↩︎

, 16. ↩︎

See . ↩︎

, 36, 40–41. ↩︎

; for an in-depth study of the ship model and its cultural context, see . A digital supplement to , including a 3-D reconstruction of the model, can be found at http://www.vizin.org/Gurob/Gurob.html. ↩︎

; . ↩︎

, 165, 173–74. ↩︎

For the origins of plate armor in the Aegean and Europe, see ; see for the possible role of mercenaries in the networks of exchange. ↩︎

, 96. ↩︎

The Tawagalawa Letter is a famous Hittite text detailing the exploits of a certain Piyamaradu and Tawagalawa: Taw.§8, 59–62; see , 28. ↩︎

, 206, proposes that the Mycenaeans themselves may have initially arrived in the Aegean as small bands of mercenaries. He suggests that these early charioteers, around the latter part of the Middle Helladic II period, may possibly have been hired by the rulers of Crete, to keep strongholds on the Greek mainland in check. “These military professionals,” he writes, “would have brought back to their homeland [which Drews situates in southern Caucasia, most likely in what is now Armenia; see 217–28, esp. 222] tales about a metal-rich land that was ripe for a takeover.” They eventually turned on their former masters. ↩︎

See, for example, . ↩︎

See , 250–58; . ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 254. ↩︎

, 17. See also S. Wachsmann in , 61–62, no. 47. ↩︎

, 14. ↩︎

, 439. ↩︎

Papyrus: London, British Museum, EA10060, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA10060; Trismegistos no. 380901, https://www.trismegistos.org/text/380901; , 171–75. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Abbas 2017

- Abbas, Mohamed Raafat. 2017. “A Survey of the Military Role of the Sherden Warriors in the Egyptian Army during the Ramesside Period.” Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne 10:7–23.

- Aruz, Benzel, and Evans 2008

- Aruz, Joan, Kim Benzel, and Jean M. Evans, eds. 2008. Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Bachhuber 2006

- Bachhuber, Christoph. 2006. “Aegean Interest on the Uluburun Ship.” American Journal of Archaeology 110, no. 3 (July): 345–63.

- Bouzek 1994

- Bouzek, Jan. 1994. “Late Bronze Age Greece and the Balkans: A Review of the Present Picture.” Annual of the British School at Athens 89:217–34.

- Bouzek 2018

- Bouzek, Jan. 2018. Studies of Homeric Greece. Prague: Karolinum Press, Charles University.

- Bryce 2016

- Bryce, Trevor. 2016. “The Land of Hiyawa (Que) Revisited.” Anatolian Studies 66:67–79.

- Causey 2011

- Causey, Faya. 2011. Amber and the Ancient World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Cline 1996

- Cline, E. H. 1996. “Aššuwa and the Achaeans: The ‘Mycenaean’ Sword at Hattušas and Its Possible Implications.” Annual of the British School at Athens 91:137–51.

- Drews 2017

- Drews, Robert. 2017. Militarism and the Indo-Europeanizing of Europe. London: Routledge.

- Emanuel 2014a

- Emanuel, Jeffrey P. 2014a. “Odysseus’ Boat? New Mycenaean Evidence from the Egyptian New Kingdom.” In Discovery of the Classical World: An Interdisciplinary Workshop on Ancient Societies, a lecture series presented by the Department of the Classics at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:24013723.

- Emanuel 2014b

- Emanuel, Jeffrey P. 2014b. “Sailing from Periphery to Core in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean.” In There and Back Again—the Crossroads II, edited by Jana Mynářová, Pavel Onderka, and Peter Pavúk, 163–79. Prague: Faculty of Arts, Charles University.

- Emanuel 2017

- Emanuel, Jeffrey P. 2017. Black Ships and Sea Raiders: The Late Bronze–Early Iron Age Context of Odysseus’ Second Cretan Lie. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

- Gardiner 1941

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson. 1941. “Adoption Extraordinary.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 26 (February): 23–29.

- Gardiner 1948

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson. 1948. The Wilbour Papyrus. Vol. 2, Commentary. London: Oxford University Press.

- Gasperini 2018

- Gasperini, Valentina. 2018. Tomb Robberies at the End of the New Kingdom: The Gurob Burnt Groups Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hansen 2002

- Hansen, William F. 2002. Ariadne’s Thread: A Guide to International Tales Found in Classical Literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Harding 2000

- Harding, A. F. 2000. European Societies in the Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heimpel 2003

- Heimpel, Wolfgang. 2003. Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Jung 2018

- Jung, Reinhard. 2018. “Warriors and Weapons on the Central and Eastern Balkans.” In Gold and Bronze: Metals, Technologies and Interregional Contacts in the Eastern Balkans during the Bronze Age, edited by Stefan Alexandrov et al., 240–51. Sofia: National Archaeological Institute with Museum.

- Kelder 2010

- Kelder, Jorrit M. 2010. The Kingdom of Mycenae: A Great Kingdom in the Late Bronze Age Aegean. Bethesda, MD: CDL.

- Kelder 2016

- Kelder, Jorrit M. 2016. “Een paspoort uit de Late Bronstijd? Een nieuwe interpretatie van het houten diptiek uit het Uluburun-wrak.” Tijdschrift Mediterrane Archeologie 55:1–6.

- Kristiansen and Suchowska-Ducke 2015

- Kristiansen, Kristian, and Paulina Suchowska-Ducke. 2015. “Connected Histories: The Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 BC.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 81:361–92.

- Kuniholm et al. 1996

- Kuniholm, Peter, et al. 1996. “Anatolian Tree Rings and the Absolute Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean, 2220–718 BC.” Nature 381:780–83.

- Leshtakov 2011

- Leshtakov, Lyuben. 2011. “Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Bronze Spear- and Javelinheads in Bulgaria in the Context of Southeastern Europe.” Archaeologia Bulgarica 15 (2): 25–52.

- Litzka 2011

- Litzka, Kate. 2011. “‘We Have Come from the Well of Ibhet’: Ethnogenesis of the Medjay.” Journal of Egyptian History 4 (2): 149–71.

- Longman et al. 2018

- Longman, Jack, et al. 2018. “Exceptionally High Levels of Lead Pollution in the Balkans from the Early Bronze Age to the Industrial Revolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 25 (June): E5661–E5668. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721546115.

- Manning et al. 2001

- Manning, Sturt W., et al. 2001. “Anatolian Tree Rings and a New Chronology for the East Mediterranean Bronze–Iron Ages.” Science 294, no. 5551 (December 21): 2532–35.

- Mcintyre 2004

- Mcintyre, Ben. 2004. Josiah the Great: The True Story of the Man Who Would Be King. London: Harper Perennial.

- Molloy 2012

- Molloy, Barry. 2012. “The Origins of Plate Armour in the Aegean and Europe.” In Recent Research and Perspectives on the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Angelos Papadopoulos, 273–94. Amsterdam: Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society.

- Morris 2003

- Morris, Sarah P. 2003. “Imaginary Kings: Alternatives to Monarchy in Early Greece.” In Popular Tyranny: Sovereignty and Its Discontents in Ancient Greece, edited by Kathryn A. Morgan, 1–24. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Morris 2008

- Morris, Sarah P. 2008. “Bridges to Babylon: Homer, Anatolia, and the Levant.” In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C., edited by Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, and Jean M. Evans, 435–39. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Petrie 1890

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul.

- Petrie 1891

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1891. Illahun, Kahun and Gurob, 1889–1890. London: David Nutt.

- Pulak 1998

- Pulak, Cemal. 1998. “The Uluburun Shipwreck: An Overview.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 27, no. 3 (August): 188–224.

- Pusch 1989

- Pusch, Edgar B. 1989. “Ausländisches Kulturgut in Qantir-Piramesse.” In Akten des 4. internationalen Ägyptologenkongresses. Vol. 2, Archäologie, Feldforschung, Prähistorie, edited by Sylvia Schoske, 249–56. Hamburg: Buske.

- Ruppenstein 2015

- Ruppenstein, Florian. 2015. “Did the Terms ‘Wanax’ and ‘Lāwāgetās’ Already Exist before the Emergence of the Mycenaean Palatial Polities?” Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft 18:91–107.

- Sandars 1985

- Sandars, N. K. 1985. The Sea Peoples: Warriors of the Ancient Mediterranean, 1250–1150 BC. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Schofield and Parkinson 1994

- Schofield, L., and R. B. Parkinson. 1994. “Of Helmets and Heretics: A Possible Egyptian Representation of Mycenaean Warriors on a Papyrus from el-Amarna.” Annual of the British School at Athens 89:157–70.

- Singer 2006

- Singer, Itamar. 2006. “Ships Bound for Lukka: A New Interpretation of the Companion Letters RS 94.2530 and RS 94.2523.” Altorientalische Forschungen 33 (2): 242–62.

- Spier, Potts, and Cole 2018

- Spier, Jeffrey, Timothy Potts, and Sara E. Cole, eds. 2018. Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Trimm 2017

- Trimm, Charlie. 2017. Fighting for the King and the Gods: A Survey of Warfare in the Ancient Near East. Atlanta: SBL.

- Vandkilde 2014

- Vandkilde, Helle. 2014. “Breakthrough of the Nordic Bronze Age: Transcultural Warriorhood and a Carpathian Crossroad in the Sixteenth Century BC.” European Journal of Archaeology 17 (4): 602–33.

- Varberg, Gratuze, and Kaul 2015

- Varberg, Jeanette, Bernard Gratuze, and Flemming Kaul. 2015. “Between Egypt, Mesopotamia and Scandinavia: Late Bronze Age Glass Beads Found in Denmark.” Journal of Archaeological Science 54 (February): 168–81.

- Varberg et al. 2016

- Varberg, Jeanette, et al. 2016. “Mesopotamian Glass from Late Bronze Age Egypt, Romania, Germany and Denmark.” Journal of Archaeological Science 74 (October): 184–94.

- Waal 2021

- Waal, W. J. I. 2021. “Distorted Reflections? Writing the Late Bronze Age in the Mirror of Anatolia.” In Linguistic and Cultural Interactions between Greece and the Ancient Near East: In Search of the Golden Fleece, edited by Michele Bianconi. Leiden: Brill.

- Wachsmann 2013

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2013. The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Wachsmann 2018

- Wachsmann, Shelley. 2018. “Egyptian Ship Model Sheds Light on Bronze Age Warfare and Religion.” The Iris (blog), Getty Trust, July 9, 2018. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/egyptian-ship-model-sheds-light-on-bronze-age-warfare-and-religion/.

- Whitley et al. 2005–6

- Whitley, James, et al. 2005–6. “Archaeology in Greece 2005–2006.” Archaeological Reports 52:1–112.