31. Protecting Cultural Property in Armed Conflict: The Necessity for Dialogue and Action Integrating the Heritage, Military, and Humanitarian Sectors

- Peter G. Stone

حماية الممتلكات الثقافية في النزاعات المسلحة: ضرورة الحوار والتدابير التي تدمج القطاعات التراثية والعسكرية والإنسانية

بيتر ج. ستون

يتوجب علينا دومًا أثناء الحروب منح الأولوية لحماية المدنيين. يتمثّل أحد الجوانب المتداخلة والتي تشكل جزءًا لا يتجزأ من هذه المسألة في حماية الممتلكات الثقافية للمدنيين التي تمنح صلات ملموسة وغير ملموسة بالماضي، وتساعد في تكوين هويتهم ورفاههم، والوصول إلى مجتمعات صحية وآمنة ومستدامة ويسودها السلام.

ملخص

أولًا، يُحدد الفصل دور ومهمة وتطلعات منظمة. الدرع الأزرق" (Blue Shield)، وهي هيئة استشارية تابعة لمنظمة الأمم المتحدة للتربية والعلم والثقافة (اليونسكو) فيما يتعلق بحماية الممتلكات الثقافية (cultural property protection, CPP) في حالة النزاعات المسلحة، والتي تركّز على الحاجة لوجود شراكة بين التراث والمستويين الإنساني والرسمي. ثانيًا، يسرد الفصل التاريخ الطويل، بشكل غير متوقع ربما، لحماية الممتلكات الثقافية كمفهوم ذو تطبيقات عملية بالنسبة لأولئك المنخرطين في نزاع مسلح. ثالثًا، يناقش الفصل السبب وراء وجوب الاهتمام على المستويين الإنساني والرسمي بحماية الممتلكات الثقافية، وما يتوجب القيام به على مستوى التراث ليكتسب زخمًا مع هذين العامِلَين المرافِقَين غير المتوقعين للوهلة الأولى. رابعًا، يُحدد الفصل بعض المخاطر الرئيسية التي تهدد الممتلكات الثقافية في حالة النزاعات المسلحة. وأخيرًا، يُقدِّم رؤية حول الدور المستقبلي الذي ستضطلع به حماية الممتلكات الثقافية خلال النزاعات المسلحة.

武装冲突中的文化财产保护:遗产、军队及人道主义部门进行对话与行动的必要性

皮特·G·斯通 (Peter G. Stone)

在战争中,我们必须始终优先保护平民。其中一个不可分割的方面是保护平民的文化财产,他们的文化财产与历史有着有形和无形的联系,有助于人民身份认同的形成、建立健康、和平、安全和可持续发展的社群,并带来福祉。

摘要

本章探讨了五个相互关联的问题。首先,文章概括了蓝盾组织的职责、使命与抱负,这个联合国教科文组织下属的咨询组织能够在发生武装冲突时为文化财产提供保护 (cultural property protection, CPP)。该组织强调了遗产、人道主义以及军队部门之间合作的必要性。其次,文章简述了文化财产保护尤为悠久的历史,而文化财产保护这一概念对武装冲突中涉及的人员具有实际的含义。第三,文章讨论了军队与人道主义部门应重视文化财产保护的原因,以及遗产部门为吸引这些看似不可能的合作伙伴的兴趣需要采取的行动。第四,文章列举了武装冲突中文化财产面临的部分主要威胁。最后,作者对未来武装冲突中文化财产保护的作用做出了预测。

In war we must always prioritize the protection of civilians. An indivisibly intertwined aspect of this is the protection of their cultural property, which gives tangible and intangible links to the past, helping provide their identity and well-being, and the achievement of healthy, peaceful, secure, and sustainable communities.

Abstract

This chapter addresses five interrelated issues. First, it outlines the role, mission, and aspirations of the Blue Shield organization, an advisory body to UNESCO on cultural property protection (CPP) in the event of armed conflict, which emphasizes the need for partnership between the heritage, humanitarian, and uniformed sectors. Second, it sketches the perhaps unexpectedly long history of CPP as a concept with practical implications for those involved in armed conflict. Third, it discusses why the uniformed and humanitarian sectors should be interested in CPP and what the heritage sector needs to do to gain traction with these, at first glance perhaps unlikely, bedfellows. Fourth, it outlines some of the key threats to cultural property in the event of armed conflict. Finally, it looks to the future role of CPP in armed conflict.

La protection des biens culturels lors d’un conflit armé : la nécessité d’un dialogue et d’une action intégrant les secteurs du patrimoine, de l’armée et de l’humanitaire

Peter G. Stone

En temps de guerre, nous devons toujours donner la priorité à la protection des populations civiles. Un aspect s’y liant de manière étroite et indivisible est la protection de leurs biens culturels, lesquels confèrent des liens matériels et immatériels au passé, contribuant de ce fait à l’identité et au bien-être des personnes, ainsi qu’à la création de communautés saines, paisibles, sûres et durables.

Résumé

Ce chapitre traite de cinq questions interdépendantes. Premièrement, il définit le rôle, la mission et les aspirations de l’organisation Bouclier bleu (Blue Shield), un organe consultatif de l’UNESCO sur la protection des biens culturels (Cultural Property Protection, CPP) en cas de conflit armé. Il s’attache à promouvoir la nécessité d’un partenariat entre les secteurs du patrimoine, de l’humanitaire et de l’armée. Deuxièmement, il décrit l’histoire étonnamment longue de la protection des biens culturels en tant que concept ayant des implications pratiques pour ceux qui sont aux prises avec un conflit armé. Troisièmement, il s’interroge sur les raisons pour lesquelles les secteurs de l’armée et de l’humanitaire devraient s’intéresser à la protection des biens culturels, et des actions que le secteur du patrimoine a besoin d’entreprendre pour tirer parti de ces partenaires, qui pourraient sembler improbables de prime abord. Quatrièmement, il esquisse certaines des menaces majeures auxquelles les biens culturels se trouvent confrontés lors d’un conflit armé. Enfin, il examine le rôle futur de la protection des biens culturels dans un conflit armé.

Защита культурных ценностей в условиях вооруженного конфликта. Необходимость диалога и действий, объединяющих культурное, военное и гуманитарное направления

Питер Г. Стоун

На войне мы всегда должны отдавать приоритет защите гражданского населения. Неразделимо связана с этой задачей необходимость защиты культурных ценностей, которые служат материальной и нематериальной связью с прошлым, помогают формировать самосознание и благосостояние, а также строить здоровые, мирные, безопасные и устойчивые сообщества.

Краткое содержание

Данная глава посвящена пяти взаимосвязанным вопросам. Во-первых, она описывает роль, миссию и цели Голубого щита (Blue Shield), консультативного комитета ЮНЕСКО по вопросам защиты культурных ценностей (cultural property protection, CPP) в случае вооруженных конфликтов, и подчеркивает необходимость партнерства между отделом, отвечающим за вопросы культурного наследия, и гуманитарными, военными и полицейскими направлениями. Во-вторых, данная глава обрисовывает, вероятно, неожиданно долгую историю концепции защиты культурных ценностей и ее практические последствия для сторон, вовлеченных в вооруженных конфликт. В-третьих, авторы объясняют, почему военный, полицейский и гуманитарный отделы должны быть заинтересованы в защите культурных ценностей, и что должен сделать отдел культурного наследия, чтобы заручиться поддержкой этих, на первый взгляд, неперспективных партнеров. В-четвертых, здесь перечисляются основные угрозы культурным ценностям в ситуации вооруженных конфликтов. Наконец, высказываются соображения относительно будущего защиты культурных ценностей в вооруженных конфликтах.

La protección de la propiedad cultural en conflictos armados: diálogo y acciones necesarios para integrar el patrimonio, las fuerzas armadas y los sectores humanitarios

Peter G. Stone

En tiempos de guerra, debemos siempre priorizar la protección de los civiles. Un aspecto indisolublemente relacionado con ello es la protección de la propiedad cultural, que establece lazos tangibles e intangibles con el pasado, ayudando a proporcionar identidad y bienestar, así como a lograr comunidades sanas, pacíficas, seguras y sustentables.

Resumen

Este capítulo aborda cinco cuestiones relacionadas. En primer lugar, plantea el papel, la misión y las aspiraciones de la organización Escudo Azul, un órgano consultivo de la Unesco sobre la protección de los bienes culturales (CPP, por sus siglas en inglés) en caso de conflicto armado, que pone de relieve la necesidad de que se establezcan colaboraciones entre los sectores patrimonial, humanitario y uniformado. En segundo lugar, esboza la quizás inesperadamente larga historia de la CPP como un concepto con implicaciones prácticas para los involucrados en un conflicto armado. En tercer lugar, plantea por qué los sectores uniformado y humanitario deberían interesarse en la CPP y qué debe hacer el sector patrimonial para ganar terreno con estos otros dos sectores que, a simple vista, podrían parecer aliados poco probables. En cuarto lugar, delinea algunas de las amenazas clave a las que se enfrentan los bienes culturales en caso de conflicto armado. Por último, se centra en el rol futuro de la CPP en situaciones de conflicto armado.

Where they burn books, they will in the end burn people.1

This chapter explores cultural property protection (CPP) in armed conflict and is written through the lens of the international nongovernmental organization (NGO) the Blue Shield, an advisory body to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Committee for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. It addresses five interrelated issues. First, the role, mission, and aspirations of the Blue Shield are outlined, which emphasize the need for partnership between the heritage,2 humanitarian, and uniformed sectors; the latter include armed forces, police, customs, and emergency services. Second, the perhaps unexpectedly long history of CPP as a concept is sketched, with practical implications for those involved in armed conflict. Third, partly drawing on this history, the chapter discusses why the uniformed and humanitarian sectors should be interested in CPP, and what the heritage sector needs to do to gain traction with these, at first glance perhaps unlikely, bedfellows. Fourth, it outlines some of the key threats to cultural property in the event of armed conflict. Finally, it looks to the future role of CPP in armed conflict.

Since the early 2000s, the protection of cultural property has become a topic of increased interest. This follows its use, manipulation, and destruction during the fighting in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, its targeting in conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq since the early 2000s, and the more recent extremes of the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS, also known as ISIL or Da’esh). Despite this rising interest, almost no attention was paid to CPP during the political or military planning of the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the coalition led by the United States and the United Kingdom.3 When the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), perhaps the world’s leading humanitarian organization, was contacted in early 2003 regarding the protection of some of the world’s earliest cultural property spread across Iraq, its response was that the ICRC concentrated on the protection of people and did not want to introduce confusion by also working to protect cultural property.

The Blue Shield

The Blue Shield was created in 1996 by the International Council on Archives (ICA), the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), and the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), known as the “Founding Four” organizations. It is established as an international NGO under Dutch law that is “committed to the protection of the world’s cultural property, and is concerned with the protection of cultural and natural heritage, tangible and intangible, in the event of armed conflict, natural- or human-made disaster.”4 The Blue Shield currently comprises nearly thirty national committees, a number growing all the time, and an international arm, Blue Shield International (BSI), which comprises a board elected by the national committees and the Founding Four, and a small secretariat (one full-time and one part-time staff member, currently based at and funded by Newcastle University in the United Kingdom). The Blue Shield is committed to joint action, independence, neutrality, professionalism, and respect of cultural identity, and is a not-for-profit organization.5

The primary context for the Blue Shield is international humanitarian law (IHL), and in particular, the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and its two protocols (1954 and 1999). It also works more generally within the context of the UN (e.g., Security Council resolutions 2199, 2347, and 2368) and UNESCO’s cultural conventions and wider cultural protection strategy. It is also informed by international initiatives regarding natural/human-made disasters, such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. The organization has chosen to expand its remit from solely the protection of tangible cultural property during armed conflict, as identified in Article 1 of the 1954 Hague Convention, to one acknowledging that all cultural property, tangible and intangible, cultural and natural, is a crucial foundation for human communities. With this in mind, BSI coordinates and sets the framework for its own work and that of the national committees through six areas of activity: policy development; coordination within the Blue Shield and with other organizations; proactive protection and risk preparedness; education, training, and capacity building; emergency response; and postdisaster recovery and long-term activity.6 All its work emphasizes the indivisible link between the protection of people and their cultural property, and the idea that such cultural property is the tangible and intangible link to the past that helps to provide individuals and communities with a sense of place, identity, belonging, and through these, well-being, giving people a reason for living. Undermining this by allowing, or, worse, causing, the unnecessary destruction of cultural property removes a fundamental building block for the delivery of healthy, peaceful, secure, and sustainable communities.

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” and notes that “the health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent on the fullest co-operation of individuals and States.”7 The Blue Shield prioritizes the safety and social, mental, and economic well-being of people and their communities, but emphasizes that the protection of their cultural property is an indivisibly intertwined factor contributing to their well-being.

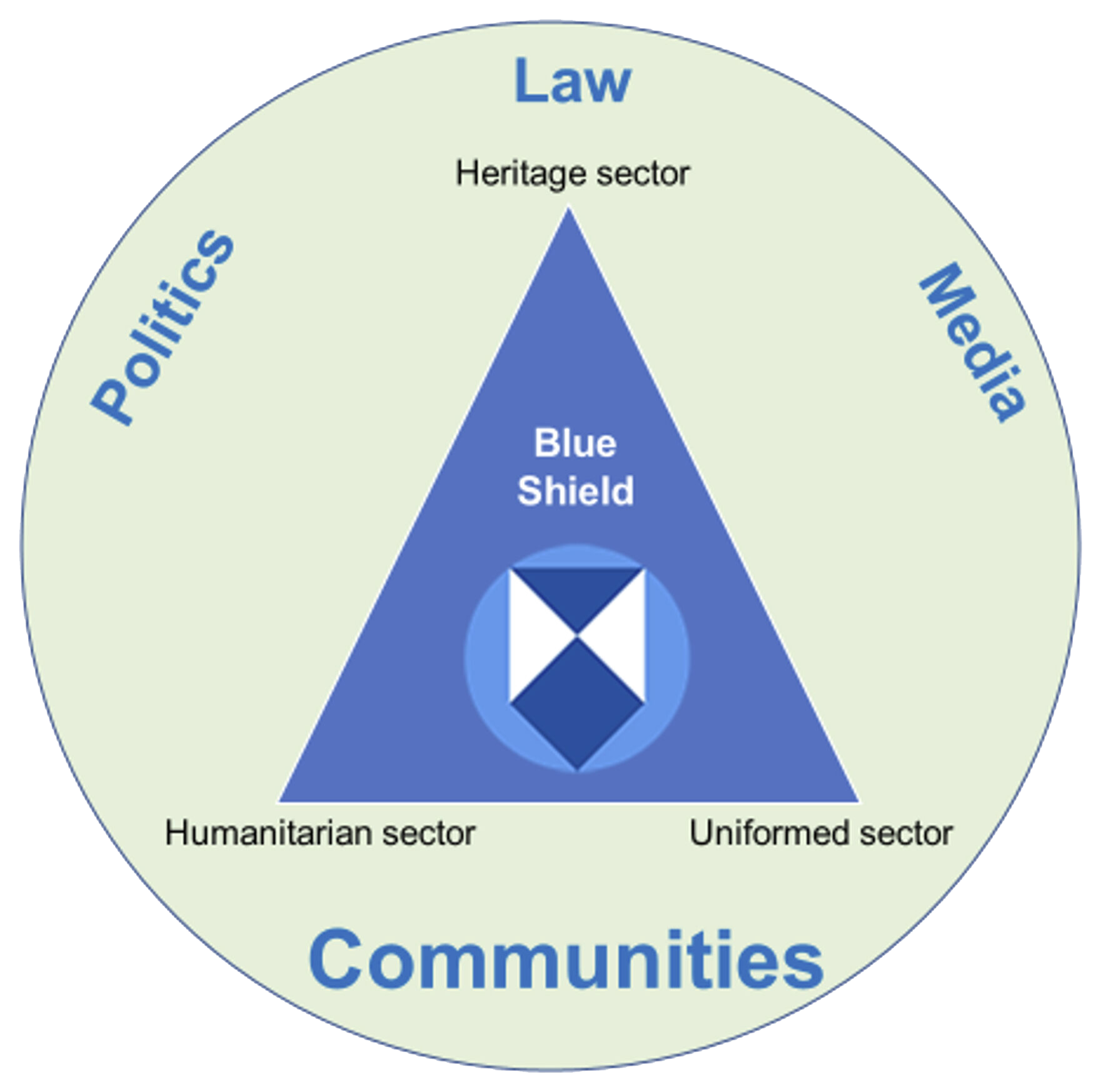

Over the last decade there has been a growing realization within the Blue Shield that, in order to help sustain such communities impacted by armed conflict, it must work across the heritage, humanitarian, and uniformed sectors to emphasize the importance of, and value to, these sectors’ own agendas of integrating good cultural property protection into their thinking and practice. Strong and stable communities are prime goals for both the uniformed and humanitarian sectors. CPP cannot be a heritage-only aspiration, for if it remains so, it is doomed. To this end the Blue Shield has developed formal agreements with uniformed, humanitarian, and heritage partners, including the ICRC, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the UN peacekeeping force in Lebanon, and, in process, UNESCO. This structure is depicted in the following diagram (fig. 31.1).

Figure 31.1

Figure 31.1The three points of the triangle show the interdependence of the three sectors, with the internal “safe space” within the triangle available for dialogue to mutually understand the importance of good CPP to the goals and aspirations of all three sectors and to identify proactive actions relating to all sectors to implement good CPP. The triangle is set within the wider context of political, legal, and media influences, and, of critical importance, communities.

In order for this relationship to work, and for the uniformed and humanitarian sectors to take CPP seriously, there are three key factors that the heritage sector needs to take into account. First, CPP has to be presented in such a way that it fits existing uniformed and humanitarian agendas, and not as a heritage-specific (read “irrelevant”) additional burden. This means emphasizing the indivisible link between the protection of people and their cultural property. Allowing or causing the unnecessary destruction of cultural property can undermine military and/or humanitarian mission success, whereas incorporating CPP can help achieve successful outcomes. The social, mental, and economic well-being of individuals and communities must be prioritized, but the case must equally be made that CPP is an intertwined, significant, contributory activity helping to achieve this priority. Second, the heritage sector must acknowledge the constraints under which the uniformed and humanitarian sectors work, understanding their existing priorities and concerns. And third, to be effective the partnership must be developed in peacetime, working for the long, medium, and short term, which will continue during armed conflict and post-conflict stabilization, and which clearly shows the importance of CPP to the uniformed and humanitarian agendas and how it can fit their existing practice. The Blue Shield refers to this as the “4 Tier Approach.”8

This approach is bearing fruit, and the rather negative response noted above from the ICRC in 2003 has also changed. Yves Daccord, then the ICRC director-general, stated in 2020 that “protecting cultural property and cultural heritage against the devastating effects of war unfortunately remains a humanitarian imperative, today perhaps more than ever.”9

A Brief History of Cultural Heritage Protection

Military theorists and commentators have discussed the methods by which war should be fought for millennia. The bulk of these writings have related to what we might now refer to as the humanitarian aspects of war, which is part of what militaries refer to as the “law of armed conflict” (LOAC). This includes the treatment of civilians and military prisoners, whether it is permissible to target civilian property, and whether it is either permissible or good military practice to destroy crops and/or other means of survival and livelihood.10 One of the earliest of these authors was the Chinese theorist Sun Tzu, writing around the sixth century BCE.11 He was very clear that fighting in war should be an absolute last resort: it was much better to defeat an enemy without spilling the blood of noncombatants or destroying property or crops, as, put simply, the defeated would be more willing to accept their fate if their country was left intact. In his writing, Sun Tzu almost anticipates the thirteenth-century writings of St. Thomas Aquinas discussing what became known as “just war theory”: when a war should be waged and if it could be justified (jus ad bellum), and how it should be waged (jus in bello).12 Neither author specifically mentioned CPP during conflict, but it can be seen as an implicit extension of their wider arguments.

Despite such theoretical writings, for hundreds if not thousands of years, soldiers were frequently paid by being allowed to loot indiscriminately. Echoing Sun Tzu and Aquinas, a number of commentators––including the ancient Greek historian Polybius,13 the seventeenth-century Dutch polymath Hugo Grotius,14 and the nineteenth-century Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz15––argued against such action, stressing that it contributed to the likelihood of future conflict and did the victors no credit. Such theorists were not alone: for example, a number of French artists and architects signed letters condemning the looting of Italian art by Napoleon, citing the importance of the original intended location and context for the art.16

The first practical record known to the author of such concern appears in the 1385 Durham Ordinances, a code of discipline for the English army drawn up immediately prior to King Richard II’s invasion of Scotland. This was essentially a general jus in bello document that also included particular instructions not to plunder religious buildings on pain of death (the same sentence as identified for rape).17 The protection of religious buildings and their contents is given effectively equal status in the code to the protection of people. While the authors may not have recognized it as such, cultural property protection had been explicitly written into an early example of national LOAC or humanitarian law.

Jumping forward, CPP was first enshrined in modern LOAC in the 1863 Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field, known as the Lieber Code. Again, this was essentially a LOAC/humanitarian document that covered the usual array of humanitarian issues, as noted above. Its primary purpose was to define what was acceptable, or not, for Union soldiers during the later American Civil War and beyond. It was thus an explicitly military document, outlining military humanitarian responsibilities, and, in Article 35, stated that “classical works of art, libraries, scientific collections . . . must be secured against all avoidable injury.”18 A number of later international LOAC documents, e.g., the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907,19 also included articles relating to CPP. These were all essentially military/humanitarian treaties that included CPP as an element of good practice in jus in bello. Given this history of the inclusion of CPP as a small part of wider treaties regarding the humanitarian conduct of conflict, it seems somewhat surprising that the modern humanitarian sector has generally failed to include such protection within its remit.

World War I saw the unprecedented destruction of cultural property, partly through the increase in scale and impact of munitions compared to earlier conflicts, and partly through the broadening of war to include bombardment of towns, both to target military factories and supply lines and to lower morale among the general population. The war also saw positive action. In 1915 a Kunstschutz (art protection) unit was created in the German army for the protection of historical buildings and collections (although its influence appears to have been fairly negligible).20 More specifically, in capturing Jerusalem in 1917, the British commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, General Edmund Allenby, issued a proclamation stating that “every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site . . . of the three religions will be maintained and protected.”21 And, showing a nuanced understanding of cultural sensitivities, he ensured that Muslim troops from the Indian army under his command were deployed to protect important Islamic sites. Someone on Allenby’s staff was thinking about which sites needed protection to ensure a smooth occupation and which troops were best to use. This is an excellent example of CPP as good military practice. It took no additional forces and made no difference to the British as to which troops protected sites and places, as they all needed something to do. However, the use of Muslim troops showed sensitivity to the beliefs and values of a large section of the local population, thereby helping to “disarm” those who might think about opposing the occupation (fig. 31.2).

Figure 31.2

Figure 31.2It was not until the 1935 Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments, known as the Roerich Pact,22 that CPP became the subject of its own international law. It states in Article 1: “The historic monuments, museums, scientific, artistic, educational and cultural institutions shall be considered as neutral and as such respected and protected by belligerents.” Unfortunately, the treaty was not taken up by the majority of the international community; it was signed by only twenty-one states, all in the Americas, and ratified by only ten.

The international heritage sector was still debating how better to protect cultural property on the eve of World War II, despite and perhaps because of the enormous damage to European cultural property, mainly along the Western Front, in World War I, and partly prompted by discussion of the Roerich Pact. During the war itself, cultural property protection was seen as the direct responsibility of the combatants, and the Western Allies and some elements of Axis forces took this duty seriously. In the German army, the Kunstschutz unit continued to operate, although much of its activity appears to have been more related to looting than protection.23 The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) unit was created within the Western Allied armies, and these “Monuments Men”––and women––made enormous efforts to protect cultural property in all theaters of war where the Western Allies fought.24 Importantly, the unit had the full backing of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander in the Western European theater from 1943.25 Regardless of LOAC, without the explicit support of senior officers such as Allenby and Eisenhower, introducing cultural property protection into military thinking would have been a significantly more difficult, if not impossible, task. Critically, both generals saw a military reason for CPP: Allenby using it to undermine potential unrest and Eisenhower to establish a positive spin on invasions that were, by their very nature, without doubt going to destroy large amounts of cultural property.

During World War II, many cultural sites, buildings, and private and public collections were, of course, destroyed, but where possible, a fair amount was done to limit the destruction and, following the war, much pillaged material was restored to prewar ownership by the Western Allies. While the scale of destruction was partially the result of the increased power of munitions, it was also due to decisions taken by both sides to target cultural property as a means of warfare, actions that today might be regarded as war crimes, such as in the Western Allies’ raids on Lübeck, Germany, in March 1942 and the so-called Baedeker raids carried out in retaliation on historical targets in England.26 The international heritage sector, reacting to the intentional and collateral devastation of much of Europe by the war, built on the inclusion of CPP in previous, more general treaties and, in 1954, developed the Hague Convention. Along with its protocols, it remains the primary piece of LOAC/IHL relating to cultural property protection.

Unfortunately, almost in parallel with the development of the convention, a key part of its potential practical support was dismantled. Article 7 requires countries to “establish in peacetime, within their armed forces, services or personnel” structures to implement CPP, yet at the end of the war the Allied Monuments Men went back to their civilian lives and, apart from somewhat limited awareness, e.g., in US Civil Affairs units, little remained of the military’s interest in cultural property protection.

Equally detrimental to protection, the heritage sector’s relationship with the military all but disappeared. Admittedly, some limited protection work was done, such as during the fighting in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s.27 And the international heritage sector responded to the deliberate targeting of, and damage to, cultural property during these conflicts, and during the UN-sanctioned Operation Desert Storm of 1991 against Iraq, by producing the Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention in 1999. However, it was not until the 2003 invasion of Iraq that CPP was brought back into sharp focus. Astonishingly, neither the United States nor the United Kingdom had ratified the convention at the time of the invasion. The United States ratified it in 2009,28 though neither of the protocols. The United Kingdom ratified all three in 2017.

Another initiative is worth mentioning, as it may partially explain the previous reluctance of the modern humanitarian sector to engage with CPP. In the late 1940s, Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin produced an early draft of what was to become the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.29 Lemkin invented the term genocide and in his early drafts wanted to include two forms of the crime: barbarity, defined as “the premeditated destruction of national, racial, religious and social collectivities,” and vandalism, or cultural genocide, defined as the “destruction of works of art and culture, being the expression of the particular genius of these collectivities.”30 He was forced to drop “vandalism” at a meeting of the UN General Assembly’s Sixth Committee (which deals with legal issues) on 25 October 1948, following twenty-five votes in favor of its omission to sixteen against, and four abstentions.31 One factor was the resistance of countries with large Indigenous populations, whose governments feared that a legal prohibition against cultural genocide might be used against them by those populations for past sins. Regardless of the reason, the removal of cultural genocide from the convention must surely have been, perhaps subconsciously, a factor in the failure of the humanitarian sector to acknowledge cultural property protection as part of its remit. While CPP can be seen to have a long history as a small part of what would now be described as LOAC/IHL, until very recently its impact on most military and humanitarian practice has been limited, as it has not been regarded by either sector as contributing to the success of their activities.

Why Should Cultural Property Protection Matter to the Military and Humanitarians?

Many of the general problems faced by coalition forces in 2003 stemmed from the political decision to limit drastically the number of troops deployed. This was exacerbated by the failure of those planning the invasion to understand the importance of cultural property to Iraqi society, and thus its importance to military mission success. The planners therefore failed to insist on enough troops to ensure good cultural property protection.32 A further, uncomfortable, contributing factor was the loss of the close relationship between the military and heritage sectors that had existed during World War II. If the military was unaware of the importance of cultural property, much blame needs to be placed with the heritage sector. Attempting to raise such awareness a few months before the invasion was too little, too late.33 In 2002 and 2003, those advocating for the protection of cultural property by coalition troops met with occasionally sympathetic but essentially deaf ears. Such advocates, the author included, started from the wrong point of view. We argued for the protection of cultural property because they were important heritage assets. While individual officers often sympathized, they did not see the value of protecting such places and things from a military perspective. We failed to make our case that such protection could contribute to the military mission, and we were therefore ignored as others made better cases for prioritizing the limited troop numbers for other activities.

This overlapped with the heritage sector’s failure over the same period to position CPP as a key concern of the humanitarian sector, failing to make the case for the indivisible relationship between the protection of people and the protection of their cultural property. Once rebuffed by the ICRC, we accepted that the humanitarian sector was not interested, slowly learned from our mistakes, and reached out. The Blue Shield now endeavors to address these shortcomings and to influence, develop, and maintain a strong relationship with the uniformed and humanitarian sectors. It argues that CPP is important to the military and humanitarian sectors for six reasons.

First, people matter: cultural property protection is about the people, the population around and among whom any uniformed deployment takes place, and who are the primary focus for humanitarian organizations. As suggested above, the protection of people, enshrined as a military responsibility in wider LOAC/IHL, is indivisibly intertwined with the protection of their cultural property. This indivisibility was underlined, for example, in the fighting in the former Yugoslavia in 1992, when the slaughtered Muslim community of Brčko was buried in a mass grave sealed by the remains of its totally destroyed mosque,34 and by similar attacks on the Yezidi population and their cultural property by ISIS, starting in 2014.35

Second, legal responsibilities are a humanitarian imperative. Any military or humanitarian mission must be fully aware of its legal responsibilities with regard to cultural property protection under IHL, and in particular the 1954 Hague Convention and the 1977 Additional Protocols to the 1949 Geneva Conventions;36 international human rights law (where the former UN special rapporteur for cultural rights suggests making access to heritage a universal human right37); international customary law; and in certain situations international criminal law, in particular the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.38 Understanding the overlap between the law of cultural property protection and more “mainstream” IHL is a key, but relatively recently accepted, humanitarian imperative.

Third, understanding and anticipating the manipulation of cultural property is a strategic imperative of which military commanders and humanitarian agencies need to be aware. Cultural property is frequently used before and during conflicts as an integral part of, usually national or substate, political strategy or tactics. Numerous conflicts, from the fighting in the former Yugoslavia,39 which included the targeted shelling of the national library in Sarajevo that led to the loss of many thousands of irreplaceable books and manuscripts,40 to the targeting of religious monuments by extreme groups, as in Timbuktu, Mali, in 2012,41 have moved targeting of cultural property firmly into those activities that potentially impinge on any military or humanitarian mission, and which constitute a war crime and arguably a crime against humanity.42 If important sites are allowed to be destroyed, problems frequently follow.43 The massive damage done in 2006 to the al-Askari Shrine in Samarra, one of the holiest Shia sites in Iraq, is frequently credited with moving the conflict from one responding to an international occupation resented by the local population to a full-scale sectarian civil war. That the shrine was left unprotected reflected a lack of political and military planning and understanding that contributed to coalition forces having to remain in Iraq for far longer than initially intended. It was not unavoidable “collateral damage” but a predictable, politically and sectarian-motivated event that might and should have been anticipated, and avoided, as it had been in 1917 Jerusalem (fig. 31.3).

Figure 31.3

Figure 31.3Very important damage is not restricted to major monuments or national libraries, and destruction impacts every community differently. While the heritage sector and much of the world reacted in horror in 2015–16 to the intentional destruction by ISIS of parts of the World Heritage Site of Palmyra in Syria, for the population of the adjacent town of Tadmur, it was almost certainly the destruction of their cemetery, which ISIS forced male members of the community to actually carry out, that had the most telling immediate impact.44 The use of such forced cultural property destruction as a punishment for minor religious crimes is thought unprecedented.45 This was a clear demonstration of subjugation, intended to demoralize and emasculate, and it had obvious and significant implications for humanitarian assistance once access became possible. The destruction and looting of parts of the World Heritage Site may also have a damaging medium- and long-term impact, as it will presumably have a serious detrimental effect on the tourist trade, on which most of the local population relies either directly or indirectly.

Fourth, cultural property protection is important to the military and humanitarian sectors because looting undoubtedly contributes to the funding of armed nonstate actors. While such looting has been almost certainly an ever-present issue since war was first waged, it is claimed frequently to have become a more organized and important aspect of modern warfare. The UN Security Council has reacted to looting in Iraq and Syria with several decisions (including resolutions 1483, 2199, and 2368) that identify looting as a significant contributory element to the funding of armed nonstate groups. Most importantly, resolution 2347 focused entirely on “the destruction of cultural heritage in armed conflict.” Despite several estimates,46 no one knows how much financial support looting has contributed to funding such actors, but the World Customs Organization notes: “Clear linkages between this form of crime and tax evasion and money laundering have been evidenced over the past years. Estimates of the size and profitability of black markets in looted, stolen or smuggled works of art are notoriously unreliable, but specialists agree that this is one of the world’s biggest illegal enterprises, worth billions of US dollars, which has naturally attracted [the] interest of organised crime.”47 To allow such a trade, much based on theft and looting, without at least acknowledgment if not mitigation, can only be judged to be poor military strategy, not least because it allows those reaping the benefit to continue to provoke humanitarian crises.

Fifth, cultural property destruction can undermine the economic recovery of a country. A military that has won a war frequently finds itself tasked with responsibility for ensuring that the post-conflict state is stable and economically viable before it can withdraw: the victor(s) must also win the peace.48 Cultural property is frequently an important element of tourism that benefits communities and countries by creating jobs and businesses, diversifying local economies, attracting high-spending visitors, and generating local investment in historical resources. With respect to the Middle East and North Africa, a 2001 World Bank report emphasized the importance of this relationship, and placed cultural property and its exploitation at the heart of the economic development of the region—especially for those countries without oil revenue.49 From military and humanitarian perspectives, the destruction of cultural property has the potential to undermine the economic recovery of a post-conflict country and may therefore lead to lengthening instability, the need for longer military and humanitarian deployments, and, quite likely, greater friction between the military and the host community, resulting in unnecessary military casualties. In such circumstances, the humanitarian role becomes more complex and difficult.

Sixth and finally, cultural property protection can be deployed as soft power. Humanitarian dollars spent on restoring religious buildings may reap the reward not only of community gratitude but also of strengthening the community to take its future into its own hands. Sadly, there are numerous recent examples where Western troops have failed to carry out CPP effectively and have antagonized the local population unnecessarily, in some instances leading to an escalation of hostilities and casualties.50 At the other end of the spectrum have been examples of excellent cultural property protection. One positive story comes from Libya in 2011, where NATO changed the proposed weapon for a planned attack on enemy forces to protect cultural property (see below). If the military gets CPP and the associated media communications right, it can make a significant contribution to winning “hearts and minds.”

Given these reasons, it seems axiomatic that the military and humanitarian sectors should take CPP as a serious responsibility. And they are beginning to do so, as evidenced by the signing of formal agreements between the Blue Shield and NATO and the ICRC. The heritage sector needs to be ready to liaise with and support such acknowledgment of responsibility.

Key Threats to Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

While the major causes globally of destruction of cultural property are probably urban expansion, mining, increase in land under cultivation, and the development of agriculture-related technologies, the Blue Shield has identified eight threats specifically related to armed conflict that need to be addressed, where applicable, by all three sectors, if they are not to turn into specific and real risks.51 Delaying or failing to address these threats will make matters worse and can raise the financial and human costs of a subsequent intervention.

First is lack of planning. The failure to plan in any coherent way for a post–Saddam Hussein Iraq prior to the 2003 invasion is a salutary lesson for the military, humanitarian, and heritage sectors.52 The specific failure to plan for CPP led to the damage or destruction of countless cultural property assets, including the widespread looting of hundreds if not thousands of archaeological sites, and the looting of museums, archives, libraries, and art galleries.53 It also contributed to the emergence of the sectarian civil war in Iraq, as demonstrated by the attacks on the al-Askari Shrine in 2006–7.54 The attacks provided the oxygen for Islamist groups to grow and increase activity, which matured into the horrors of ISIS. The group later provoked a humanitarian catastrophe, with millions becoming internally displaced persons (IDPs) and a significant increase in the number of refugees risking their lives to cross the Mediterranean to a hoped-for better life away from armed conflict. Work since 2003 has significantly raised awareness of this issue, but much still remains to be done to incorporate CPP into political, heritage, military, and humanitarian thinking and planning at the national and international levels.

Second is lack of military and humanitarian awareness. Again, significant progress has been achieved since 2003, but until a structured, long-term partnership develops between the three sectors that fits easily with existing military and humanitarian planning systems already in place and that has been accepted as the norm, military and humanitarian awareness of the potential importance of cultural property protection will be limited. Until CPP is integrated into peacetime education and training for the military and humanitarian sectors, it will not be regarded as an important consideration. The formal agreements between the Blue Shield and the ICRC and NATO are small, but extremely significant, steps toward this integration.

Third is collateral and accidental damage. By its nature, armed conflict causes significant unintended or accidental damage. It is inevitable that some cultural property will be damaged or destroyed during armed conflict. However, by raising awareness of the eight threats through good education and training, the likelihood of these turning into real risks should be lowered significantly.

Fourth is specific or deliberate targeting. Recent conflicts have seen the deliberate targeting of cultural property by armed nonstate actors as a weapon of war. On occasion, as acknowledged in the 1954 Hague Convention, even armed forces that have incorporated CPP into planning may have to target cultural property for reasons of “military necessity,” but this should happen only as a last resort, and where there is no other military option.

Fifth is looting, pillage, and the “spoils of war.” Armed conflict frequently creates a vacuum of authority in which noncombatants may loot cultural property, quite often as a last means of raising money to enable their families to eat. At the same time, foreign military or civilian personnel may buy objects as personal souvenirs or pillage items, so-called spoils of war, as communal mementos for regimental museums or dining areas. In some instances, as noted above, such activity becomes organized by nonstate armed actors as a means of income generation. Too often, private collectors of antiquities in what are known as “market countries” do not realize that the top dollar they pay for the privilege to personally own a piece of the ancient past may well be directly funding those that their country’s armed forces are fighting.

Sixth is the deliberate reuse of sites. Cultural sites are frequently reused as shelters by internally displaced people and, breaking international law, by belligerents. This almost always damages the sites and may lead to planned and unplanned looting.

Seventh is enforced neglect. Much cultural property requires, by its very nature, constant expert monitoring, yet during armed conflict, such access frequently becomes problematic and/or impossible. As a result, for example, roof tiles slip on ancient buildings, letting in rain, or essential environmental conditions in an archive can fail due to electricity interruption—both of which can cause significant damage.

And finally, eighth is development. This is a constant threat to cultural property during peacetime, but the vacuum of authority exacerbates the problem during armed conflict, as individuals demolish or encroach on cultural property for their personal gain.

There is no space to discuss means to mitigate these threats, but the need to address them is clear: if all eight threats were addressed prior to armed conflict and embedded within normal political, heritage, military, and humanitarian processes and practices, the impact of armed conflict on cultural property could be significantly reduced. This would not distract from overall mission objectives; indeed, it would perhaps contribute to them, and reduce the humanitarian impact of the conflict. The 1954 Hague Convention contains an adequate legal framework but has never been fully implemented.

A primary requirement is that military and humanitarian colleagues need to have access to lists of specific cultural property that should be protected if at all possible. The production of such lists is, technically, the responsibility of the state parties to the 1954 Hague Convention. However, in a number of recent situations, this has been impossible; led mostly by its US national committee, the Blue Shield has stepped in to produce lists as necessary, cross-checked wherever possible by colleagues from the relevant country. The current author, with colleagues in the United Kingdom and Iraq, completed an initial list for Iraq in 2003 for the UK Ministry of Defence, as did colleagues in the United States for the Department of Defense55—an attempt at good practice but uncoordinated and far too late. Similar lists have been produced by the Blue Shield for Libya, Mali, Syria, Iraq (far more detailed than in 2003), and Yemen. The aspiration for such lists is that they are transferred to the military’s so-called no strike lists, a list of places, including hospitals, education establishments, and religious buildings, that should not be targeted unless military necessity dictates otherwise. Lists of cultural property are fraught with complications.56 For example, who should set the standard and specification for such lists, and what should these be? How large should a list be? If it is too small, important cultural property will almost certainly be lost; too large, and the risk that the military will ignore the list increases, as it will be seen as an impossible constraint on mission operations. While the convention stipulates that all cultural property should be protected, it has proved to be extremely difficult to produce reliable lists of sufficient detail for libraries, archives, art museums, and galleries. This is a sad reflection on the changes since World War II, when the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, known as the Roberts Commission, listed some forty thousand cultural properties, including many important archives and libraries, and distributed them to Allied forces. Much more work needs to be done (deciding, for example, what geospatial data is used and needed) before there will be an effective, efficient, and acceptable process and template for such lists, and the Blue Shield is working with NATO and others to develop a standardized template for such information.

As an example of the value of such lists, the cooperation between cultural property experts and NATO militaries over a list of relevant heritage in Libya in 2011 was perceived as a great success. In particular, intervention forces did not target and so protected the Roman fort at Ras Almargeb, where forces loyal to the government of Muammar Gaddafi had established a communications and radar unit inside and in close proximity to the Roman building. The site was on the list of cultural property submitted to NATO and, we can only assume, had been added to the military no-strike list. As a result, its forces planned the precise destruction of military targets with very minimal shrapnel damage to the building. This proactive protection received significant positive media reporting—something NATO was somewhat unused to. This led the organization to commission an internal report, Cultural Property Protection in the Operations Planning Process, published in December 2012,57 which recommended that NATO construct its own cultural property protection policy.58 No such policy is yet in place, but a NATO-affiliated “Centre of Excellence” has been suggested that it is hoped will include CPP, and a CPP directive has been approved—the first step to the establishment of policy (fig. 31.4).

Figure 31.4

Figure 31.4Despite such moves in the right direction, a great deal more work needs to be done before CPP is accepted by the political, military, and humanitarian sectors. The Blue Shield’s six areas of activity provide a framework within which it will work toward such acceptance, forming a clear agenda of what needs to be done.

Conclusion: The Future Role of Cultural Property Protection in Armed Conflict

Cultural property protection in armed conflict will never be achieved by the heritage sector’s simply shouting that it must be taken seriously by the political, military, and humanitarian sectors. We need to show the relevance and importance of good CPP activity to all of these sectors; we also need to be inside the room in order to influence thinking and practice.

The Blue Shield’s areas of activity, and the urgent need to address the eight threats outlined in the section above, taken together with the proactive signing of agreements with key military and humanitarian organizations (and with others in the pipeline), contribute to the development of a structured vision of how CPP might be integrated effectively into political, military, and humanitarian thinking, processes, and action. It also implicitly includes the need to stimulate extensive support across the whole of the heritage sector. This raises a fundamental point: that the Blue Shield, as the primary neutral and independent organization dealing with CPP that stresses joint action and emphasizes the respect of cultural identity, should perhaps not be regarded as an explicitly heritage organization, but rather as a vehicle where all of those involved in armed conflict can come together to the benefit not of any particular organization but of the whole of humanity. As the Preamble to the 1954 Hague Convention states, “damage to cultural property belonging to any people whatsoever means damage to the cultural heritage of all [hu]mankind, since each people makes its contribution to the culture of the world.” By attempting to protect cultural property in armed conflict, the Blue Shield is attempting to protect that of all people, dead, living, and to come. As a spin-off, we may have the chance to make war slightly more humane. This is an extremely ambitious project that will not be delivered in my lifetime. However, if we do not start now, it will not be delivered in my grandchildren’s lifetime either.

Biography

- Peter G. StonePeter G. Stone is the UNESCO Chair in Cultural Property Protection (CPP) and Peace at Newcastle University, the United Kingdom, and president of the nongovernmental organization the Blue Shield, an advisory body to UNESCO on CPP in the event of armed conflict. He has worked in CPP since 2003 and has written extensively on this topic, including editing with Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq (2008) and editing Cultural Heritage, Ethics and the Military (2011). His article “The 4 Tier Approach” in The British Army Review led directly to the establishment of the Cultural Property Protection Unit in the British armed forces.

Suggested Readings

- Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War (London: Reaktion Books, 2006).

- Emma Cunliffe, Paul Fox, and Peter G. Stone, The Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict: Unnecessary Distraction or Mission-Relevant Priority? (Brussels: NATO, July 2018), NATO OPEN Publications vol. 2, no. 4, https://www.act.nato.int/images/stories/media/doclibrary/open201804-cultural-property.pdf.

- Geneva Call, Culture under Fire: Armed Non-state Actors and Cultural Heritage in War (Geneva: Geneva Call, 2018).

- Roger O’Keefe, The Protection of Cultural Property in Armed Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- RASHID International, Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA), and Yazda, Destroying the Soul of the Yazidis: Cultural Heritage Destruction during the Islamic State’s Genocide against the Yazidis (Munich: RASHID International, August 2019), https://www.yazda.org/post/new-report-cultural-heritage-destruction-during-the-islamic-state-s-genocide-against-the-yazidis.

- Laurie Rush, Archaeology, Cultural Property, and the Military (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2010).

- Peter G. Stone and Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, eds., The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2008).

Notes

From Heinrich Heine’s 1821 play Almansor. This refers to the burning of Islamic manuscripts and Muslims by the Spanish Inquisition. Peter Stone is responsible for the choice and presentation of views contained in this article and for opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the organization. ↩︎

While relying on the legal terminology of the 1954 Hague Convention, referring to “cultural property” and “cultural property protection,” the chapter uses the wider term “heritage sector” to refer to the many individuals and organizations involved in heritage, not just the very small number involved in CPP. ↩︎

Thomas Ricks, Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq (London: Penguin Books, 2006). ↩︎

Article 2.1 of the Blue Shield’s Articles of Association, https://theblueshield.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/statute-Amendments_BSI_2016-1.pdf. ↩︎

See the Strasbourg Charter of the International Committee of the Blue Shield, 2000, https://theblueshield.org/the-strasbourg-charter-2000/. ↩︎

Peter G. Stone, “Protecting Cultural Property during Armed Conflict: An International Perspective,” in Heritage under Pressure, ed. Michael Dawson, Edward James, and Mike Nevell (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2019), 153–70. ↩︎

Constitution of the World Health Organization, 1946, https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf. ↩︎

See the website of the Blue Shield, https://theblueshield.org; and Peter G. Stone, “A Four-Tier Approach to the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict,” Antiquity 87, no. 335 (2013): 166–77. ↩︎

Quoted in ICRC, “The ICRC and the Blue Shield Signed a Memorandum of Understanding,” 26 February 2020, https://www.icrc.org/en/document/icrc-and-blue-shield-signed-memorandum-understanding. ↩︎

Sahil Verma, “Sun Tzu’s Art of War and the First Principles of International Humanitarian Law,” post, Cambridge International Law Journal, 30 August 2020, http://cilj.co.uk/2020/08/30/sun-tzus-art-of-war-and-the-first-principles-of-international-humanitarian-law/. ↩︎

Sun Tzu, The Art of War (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 2002). ↩︎

Charles Guthrie and Michael Quinlan, Just War: Ethics in Modern Warfare (London: Bloomsbury, 2007). ↩︎

Margaret Miles, “Still in the Aftermath of Waterloo: A Brief History of Decisions about Restitution,” in Cultural Heritage, Ethics and the Military, ed. Peter G. Stone (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2011), 29–42. ↩︎

Hugo Grotius, On the Law of War and Peace, ed. Stephen C. Neff (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). ↩︎

Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. J. J. Graham (Ware, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1997). ↩︎

Miles, “Still in the Aftermath of Waterloo.” ↩︎

Rory Cox, “A Law of War? English Protection and Destruction of Ecclesiastical Property during the Fourteenth Century,” English Historical Review 128, no. 535 (2013): 1381–417. For the text of the Ordinances, see Anne Curry, “Disciplinary Ordinances for English and Franco–Scottish Armies in 1385: An International Code?,” Journal of Medieval History 37 (2011): 269–94. ↩︎

For the text, see Yale Law School, “General Orders No. 100: The Lieber Code,” the Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lieber.asp. ↩︎

Convention (II) with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its Annex: Regulations Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, 1899, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/150; and Convention (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its Annex: Regulations Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, 1907, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/195. ↩︎

Roger O’Keefe, The Protection of Cultural Property in Armed Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 41. ↩︎

Quoted in Firstworldwar.com, “Primary Documents: Sir Edmund Allenby on the Fall of Jerusalem, 9 December 1917,” http://firstworldwar.com/source/jerusalem_allenbyprocl.htm. ↩︎

US Committee of the Blue Shield, “Roerich Pact,” https://uscbs.org/1935-roerich-pact.html. ↩︎

Headquarters Allied Commission, Report on the German Kunstschutz in Italy between 1943 and 1945, doc. no. T/209/30/3, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom. ↩︎

Lynn Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: Vintage Books, 1995); and Lenard Woolley, A Record of the Work Done by the Military Authorities for the Protection of the Treasures of Art and History in War Areas (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1947). ↩︎

Greg Bradsher and Sylvia Naylor, “General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Protection of Cultural Property,” blog of the Textual Records Division at the National Archives, 10 February 2014, https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2014/02/10/general-dwight-d-eisenhower-and-the-protection-of-cultural-property/. ↩︎

Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War (London: Reaktion Books, 2006). ↩︎

Joris Kila, Heritage under Siege (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2012). ↩︎

The full US Senate voted to ratify the treaty on 25 September 2008, but the United States did not deposit its instrument of ratification until 13 March 2009. ↩︎

See John Cooper, Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). ↩︎

Raphael Lemkin, “The Evolution of the Genocide Convention,” Lemkin Papers, New York Public Library, cited in Bevan, The Destruction of Memory, 210. ↩︎

Cooper, Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention, 158. ↩︎

Ricks, Fiasco; and Lawrence Rothfield, The Rape of Mesopotamia: Behind the Looting of the Iraq Museum (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). ↩︎

Peter G. Stone, “The Identification and Protection of Cultural Heritage during the Iraq Conflict: A Peculiarly English Tale,” Antiquity 79, no. 4 (2005): 933–43. ↩︎

UN Security Council, Final Report of the UN Commission of Experts Established Pursuant to SC Res. 780 (1992), UN doc. S/1994/674, 27 May 1994, Annex X: Mass Graves, http://heritage.sensecentar.org/assets/bosnia-herzegovina/sg-5-05-destroyed-buildings-eng.pdf. ↩︎

See the website of Yazda, https://www.yazda.org/. ↩︎

See ICRC, “The Geneva Conventions and Their Commentaries,” https://www.icrc.org/en/war-and-law/treaties-customary-law/geneva-conventions. ↩︎

See Karima Bennoune, Report of the Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights, General Assembly, UN doc. A/71/317, 9 August 2016, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/CulturalRights/Pages/Intentionaldestructionofculturalheritage.aspx. ↩︎

For the text of the statute, see ICC, https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf. ↩︎

See, e.g., Helen Walasek, Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2015). ↩︎

Munevera Zećo and William B. Tomljanovich, “The National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Current War,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 66, no. 3 (1996): 294–301. ↩︎

UNESCO, “UNESCO Director General Condemns Destruction of Nimrud in Iraq,” 6 March 2015, http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1244. The destruction of religious sites in Timbuktu led to the first prosecution at the International Criminal Court for crimes against cultural property: see ICC, “Al Mahdi Case,” https://www.icc-cpi.int/mali/al-mahdi. ↩︎

UNESCO, “UN Security Council Adopts Historic Resolution for the Protection of Heritage,” 24 March 2017, https://en.unesco.org/news/security-council-adopts-historic-resolution-protection-heritage. ↩︎

Benjamin Isakhan, “The Islamic State Attacks on Shia Holy Sites and the ‘Shrine Protection Narrative’: Threats to Sacred Space as a Mobilization Frame,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 4 (2018): 1–25. ↩︎

Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, personal communication with the author. ↩︎

See American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR), “Weekly Report 73–74,” 23 December 2015–5 January 2016, http://www.asor.org/chi/reports/weekly-monthly/2016/73-74. ↩︎

Sarah Cascone, “Syria’s Cultural Artefacts Are Blood Diamonds for ISIS,” Artnet, 9 September 2014, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/syrias-cultural-artifacts-are-blood-diamonds-for-isis-96814; and Simon Cox, “The Men Who Smuggle the Loot That Funds IS,” BBC, 17 February 2015, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-31485439. ↩︎

World Customs Organization, “Cultural Heritage Programme,” http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/enforcement-and-compliance/activities-and-programmes/cultural-heritage-programme.aspx. ↩︎

Thomas Hammes, The Sling and the Stone: On War in the 21st Century (St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press, 2004). ↩︎

World Bank, Cultural Heritage and Development: A Framework for Action in the Middle East and North Africa (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2001), vii. ↩︎

See, e.g., Geoffrey Corn, “‘Snipers in the Minaret: What Is the Rule?’ The Law of War and the Protection of Cultural Property: A Complex Equation,” The Army Lawyer 2005, no. 7 (2005): 28–40; John Curtis, Report on Meeting at Babylon 11th–13th December 2004 (London: British Museum, January 2004); and Michael P. Phillips, “Learning a Hard History Lesson in ‘Talibanistan,’” Wall Street Journal, 14 May 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124224652409516525.html. ↩︎

See Blue Shield, “Threats to Heritage,” https://theblueshield.org/why-we-do-it/threats-to-heritage/. ↩︎

See Ricks, Fiasco. ↩︎

Peter G. Stone and Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, eds., The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2008). ↩︎

See, e.g., BBC, “Iraqi Blast Damages Shia Shrine,” 22 February 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/4738472.stm; Damien Cave and Graham Bowley, “Shiite Leaders Appeal for Calm after New Shrine Attack,” New York Times, 13 June 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/13/world/middleeast/13cnd-samarra.html; and Benjamin Isakhan, “Heritage Destruction and Spikes in Violence: The Case of Iraq,” in Cultural Heritage in the Crosshairs, ed. Joris Kila and James Zeidler (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2013), 237–38. ↩︎

Stone, “The Identification and Protection of Cultural Heritage”; and McGuire Gibson, “Culture as Afterthought: US Planning and Non-planning in the Invasion of Iraq,” Conservation & Management of Archaeological Sites 11, nos. 3–4 (2009): 333–39. ↩︎

Peter G. Stone, “War and Heritage: Using Inventories to Protect Cultural Property,” Conservation Perspectives (the Getty Conservation Institute newsletter), Fall 2013, http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/28_2/war_heritage.html; and Emma Cunliffe, “No Strike Lists—From Use to Abuse?,” Heritage in War (blog), March 2020, https://www.heritageinwar.com/single-post/2020/01/24/trump-and-iranian-cultural-property-heritage-destruction-war-crimes-and-the-implications. ↩︎

NATO, Cultural Property Protection in the Operations Planning Process (Lisbon, Portugal: NATO’s Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre, 2012), unclassified report. ↩︎

NATO, Cultural Property Protection in the Operations Planning Process, iv. ↩︎