ثقافة المخطوطات في اليمن عرضة للهجوم

سابين شميدكي

التقاليد الأدبية اليمنية الزيدية هي من بين التقاليد الأكثر غنى وتنوعًا في الحضارة الإسلامية. ولكن هذا التراث الثقافي الثمين عرضة لخطر وشيك يهدده. حماية جزء هام من الإرث الثقافي لليمن والحفاظ عليه وعلى تقاليده الغنية في مجال المخطوطات ستكون أمرًا محوريًا لجهة توفير دعامة قوية للهوية والانتماء لأجيال المستقبل من اليمنيين.

ملخص

التقاليد الأدبية الزيدية هي من بين التقاليد الأكثر غنى وتنوعًا في الحضارة الإسلامية. والجزء الأبرز والأكبر إلى حد بعيد من مجموعة المخطوطات الزيدية موجود ضمن العديد من المكتبات العامة والخاصة في اليمن. ومن المقتنيات الهامة إلى حد كبير أيضًا هي تلك المخطوطات اليمنية الموجودة في الخارج، ولا سيما مصر والمملكة العربية السعودية وتركيا وإيران والعراق، بالإضافة إلى أوروبا والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ونظرًا لضعف الدراسات المتعلقة بالمخطوطات الزيدية، تتضاعف التحديات الناتجة عن التشتت واسع النطاق للمخطوطات والحالة الكارثية السائدة في اليمن. وما يزيد الوضع سوءًا هو أن مكتبات المخطوطات في اليمن نفسه عرضة لخطر وشيك. حاربت السلطات اليمنية على مدى العقود الماضية عمليات الإتجار غير المشروع بالمخطوطات، كما تعرضت الكثير من المكتبات الخاصة في البلاد لأضرار جسيمة، أو تم نهبها أو تدميرها جراء الاضطرابات السياسية والحرب. يُشكل الصراع المستمر خطرًا محدقًا لا يتربّص بالسكان المحليين فحسب، بل كذلك بالتراث الثقافي، ولا سيما المكتبات الكثيرة الموجودة هناك. حماية جزء هام من الإرث الثقافي لليمن والحفاظ عليه وعلى تقاليده الغنية في مجال المخطوطات ستكون أمرًا محوريًا لجهة توفير دعامة قوية للهوية والانتماء لأجيال المستقبل من اليمنيين.

遭到袭击的也门手稿文化

莎宾娜·施密特克 (Sabine Schmidtke)

也门栽德派的文字传统丰富多样,在伊斯兰教文明中享有崇高地位。这一珍贵的文化遗产濒临消失。保护与传承也门文化遗产中这一重要部分对于为也门后代带来强烈的认同感与归属感至关重要。

摘要

也门栽德派的文字传统丰富多样,在伊斯兰教文明中享有崇高地位。也门的多座公共和私人图书馆均藏有最为重要、迄今为止数量最多的栽德派手稿。其它地区和国家,尤其是埃及、沙特阿拉伯、土耳其、伊朗、伊拉克、欧洲与美国收藏的也门手稿同样意义非凡。鉴于栽德派研究领域中学术状况的不堪,如今也门面临着手稿四散、损失惨重的重重挑战。更为糟糕的是,也门的各大手稿图书馆也岌岌可危。在过去的数十年间,也门当局不断对手稿进行非法交易,国内多座私人图书馆因政治骚乱和战争遭到严重破坏、抢劫、甚至被摧毁:持续的冲突对当地人民及包括多座图书馆在内的文化遗产造成了严重的威胁。保护与传承也门文化遗产中这一重要部分对于为也门后代带来强烈的认同感与归属感至关重要。

The Yemeni-Zaydi literary tradition is among the richest and most variegated traditions within Islamic civilization. This precious cultural heritage is under imminent threat. Protecting and preserving an important part of Yemen’s cultural legacy—its rich manuscript tradition—will be key to providing future generations of Yemenis with a firm sense of identity and belonging.

Abstract

The Zaydi literary tradition is among the richest and most variegated traditions within Islamic civilization. The most significant and by far the largest collections of Zaydi manuscripts are housed by the many public and private libraries of Yemen. Of great importance are also holdings of Yemeni manuscripts that are kept elsewhere, especially in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq, as well as in Europe and the United States. In view of the poor state of scholarship in the area of Zaydi studies, the challenges that result from the significant dispersal of the material and the disastrous situation in present-day Yemen are manifold. To make matters worse, the manuscript libraries in Yemen itself are under imminent threat. Over the past several decades Yemeni authorities have constantly fought the illicit trafficking of manuscripts, and many of the country’s private libraries have been severely damaged, looted, or even destroyed as a result of political turmoil and war; continued conflict constitutes an imminent threat not only to the local population but also to its cultural heritage, including its many libraries. Protecting and preserving an important part of Yemen’s cultural legacy—its rich manuscript tradition—will be key to providing future generations of Yemenis with a firm sense of identity and belonging.

La culture manuscrite du Yémen est prise d’assaut

Sabine Schmidtke

Au sein de la civilisation islamique, la tradition littéraire zaïdite-yéménite est l’une des plus riches et des plus variées. Ce patrimoine culturel précieux fait l’objet d’une menace imminente. La protection et la préservation d’une partie importante du patrimoine culturel du Yémen, à savoir sa riche tradition de manuscrits, seront cruciales pour transmettre aux générations futures de Yéménites une conscience affermie de leur identité et de leur appartenance.

Résumé

Au sein de la civilisation islamique, la tradition littéraire zaïdite est l’une des plus riches et des plus variées. Les plus importantes, et de loin les plus vastes, collections de manuscrits zaïdites sont hébergées par les nombreuses bibliothèques publiques et privées du Yémen. Les manuscrits yéménites conservés ailleurs, notamment en Égypte, en Arabie Saoudite, en Turquie, en Iran, en Irak, ainsi qu’en Europe et aux États-Unis, sont également d’une importance capitale. Au regard de l’état déplorable de la recherche dans le domaine des études zaïdites, les défis résultant de la dispersion considérable des matériaux et de la situation désastreuse du Yémen actuel sont multiples. Aggravant encore les choses, les bibliothèques de manuscrits au Yémen font elles-mêmes l’objet d’une menace imminente. Au cours des décennies passées, les autorités yéménites ont lutté sans relâche contre le trafic illicite de manuscrits, et nombre des bibliothèques privées du pays ont été gravement endommagées, pillées ou même détruites en raison des troubles politiques et de la guerre. La poursuite du conflit représente une menace imminente non seulement pour la population locale, mais aussi pour son patrimoine culturel, notamment ses nombreuses bibliothèques. La protection et la préservation d’une partie importante du patrimoine culturel du Yémen, à savoir sa riche tradition de manuscrits, seront cruciales pour transmettre aux générations futures de Yéménites une conscience affermie de leur identité et de leur appartenance.

Рукописная культура Йемена под ударом

Сабин Шмидтке

Литературная традиция Зейдитов в Йемене является наиболее богатой и разнообразной в исламской цивилизации. Это бесценное культурное наследие находится под неминуемой угрозой. Защита и сохранение важнейшей составляющей йеменского культурного наследия, его богатой рукописной традиции, станет основой для формирования у будущих поколений йеменцев ясного самосознания и чувства культурной принадлежности.

Краткое содержание

Литературная традиция Зейдитов является наиболее богатой и разнообразной в исламской цивилизации. Крупнейшие и самые значимые коллекции рукописей Зейдитов хранятся во многих публичных и частных библиотеках Йемена. Важное значение имеют и те рукописи, которые хранятся за пределами страны, особенно в Египте, Саудовской Аравии, Турции, Иране и Ираке, а также в Европе и США. В связи с недостатком стипендий в области изучения культуры Зейдитов, существует множество сложностей, обусловленных значительным рассредоточением материала и бедственным положением в современном Йемене. Более того, библиотеки рукописей в самом Йемене находятся под неминуемой угрозой. В течение нескольких последних десятилетий власти страны непрерывно боролись с незаконной торговлей рукописями. Многие частные библиотеки серьезно пострадали, были разграблены или даже уничтожены в результате политических волнений и войн; непрерывные конфликты представляют собой неминуемую угрозу не только для местного населения, но и для культурного наследия, в том числе многих библиотек. Защита и сохранение важнейшей составляющей йеменского культурного наследия, его богатой рукописной традиции, станет основой для формирования у будущих поколений йеменцев ясного самосознания и чувства культурной принадлежности.

La cultura manuscrita de Yemen en peligro

Sabine Schmidtke

La tradición literaria yemení-zaidí es una de las tradiciones más ricas y diversas de la civilización islámica. La amenaza a este valioso patrimonio cultural es inminente. Proteger y preservar una parte significativa del legado cultural de Yemen —su rica tradición de manuscritos— será clave para proporcionar a las futuras generaciones de yemeníes un fuerte sentido de identidad y pertenencia.

Resumen

La tradición literaria zaidí es una de las tradiciones más ricas y diversas de la civilización islámica. Las colecciones de manuscritos zaidíes más significativas y sin duda numerosas se albergan en muchas bibliotecas públicas y privadas de Yemen. También son de gran importancia los fondos de manuscritos yemeníes conservados en otros lugares, especialmente en Egipto, Arabia Saudita, Turquía, Irán e Irak, así como en Europa y Estados Unidos. Dado el escaso conocimiento académico desarrollado en el área de los estudios zaidíes, son numerosos los desafíos resultantes de la gran dispersión del material y de la situación desastrosa que se vive en el Yemen actual. Para mayor desgracia, la amenaza a las bibliotecas de manuscritos del propio Yemen es inminente. Durante las últimas décadas, las autoridades yemeníes han luchado de manera continua contra el tráfico ilícito de manuscritos y muchas de las bibliotecas privadas del país se han visto gravemente dañadas, saqueadas o incluso destruidas como resultado de la agitación política y la guerra: el constante estado de conflicto constituye una amenaza inminente no solo para la población local sino también para su patrimonio cultural, lo que incluye sus muchas bibliotecas. Proteger y preservar una parte significativa del legado cultural de Yemen —su rica tradición de manuscritos— será clave para proporcionar a las futuras generaciones de yemeníes un fuerte sentido de identidad y pertenencia.

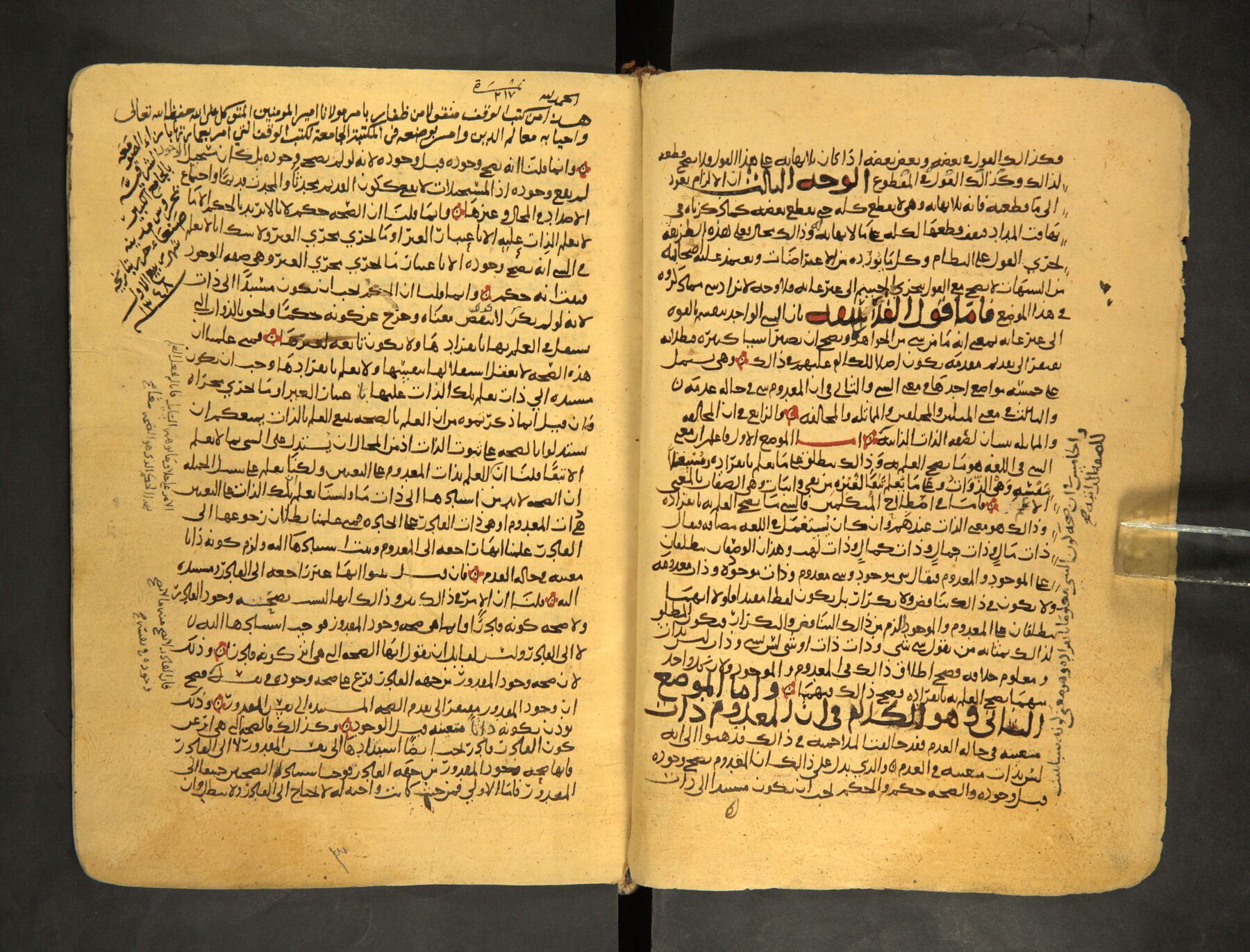

In the aftermath of the Ottoman Empire’s collapse at the end of World War I, the Yemeni highlands came under the rule of the Zaydi Hamid al-Din dynasty. Imam al-Mutawakkil ʿala llah Yahya Ḥamid al-Din (r. 1904–48) devised an idiosyncratic religio-pedagogical program to advance religion and culture in Yemen while at the same time attempting to shield its citizens from the advancements of modernity. His educational reforms included the foundation in 1926 of a “mosque university” (al-madrasa al-ʿilmiyya) where the country’s elite was educated over the next several decades. Moreover, Imam Yahya issued a decree in 1925 announcing the establishment of a public library, al-Khizāna al-Mutawakkiliyya (today Maktabat al-Awqāf), which in many ways constituted a novelty in Yemen. The imam assigned a consecrated location to the library on the premises of the Great Mosque in Sana’a, and he had a new story added for the library along the southern side of the mosque’s courtyard. The principal purpose behind the library, as spelled out in the 1925 decree, was to gather what remained of the many historical libraries dispersed all over the country and thus prevent further losses. For this purpose the imam appointed as library officials qualified scholars, who started to build up the collections. The details of this process can be gleaned from the notes that were added to each codex (fig. 13.1). These record the provenance of the individual codices and when each was transferred to the Khizāna, as well as occasional specific regulations for the codex in question. Gradually, registers of the holdings of the newly founded Khizāna were produced, culminating in a catalogue published in 1942/43 (fig. 13.2).1

Figure 13.1

Figure 13.1The catalogue, a large folio volume consisting of 344 pages and describing some eight thousand titles of both manuscripts and printed books, is a remarkable piece of work: although the information about each manuscript and printed volume is kept to a minimum, it methodically records the provenance of each item. Taken together, these data allow for an inquiry into the history of the library’s manuscript holdings (some four thousand items), dating from the tenth century up until the first decades of the twentieth, thus opening a representative window into the history of manuscript production and book culture in Yemen over the course of a millennium.2

The oldest layer of manuscripts (constituting 5 percent of the Khizāna’s total holdings), some of which were produced during the tenth and eleventh centuries, came from the library of Imam al-Mansūr bi-llāh ʿAbd Allah b. Hamza (r. 1197–1217), which was situated in his town of residence, Ẓafār, and was one of the oldest extant libraries in Yemen. Another corpus of particularly precious and old manuscripts originated in the library of the Āl al-Wazīr, a powerful Zaydi family in Yemen, whose members had been engaged in scholarship and politics since the twelfth century; some rose to power while others failed. Time and again their opponents confiscated parts of the family’s property, including their books. The codices that are recorded in the 1942/43 catalogue as originating from the library of the Āl al-Wazīr match an inventory of titles confiscated from the al-Wazīr family following the order of the Qāsimī imam al-Mutawakkil ʿala llah Ismaʿil (r. 1644–76), which was written out in 1690 and lists 131 items. According to historical accounts, the library collection of the Āl al-Wazīr, which amounted to some nine hundred codices by the mid-seventeenth century, had been divided between several branches of the family and was at risk of being lost as a result of the dispersal. The inventory was scribbled down on some empty pages of a codex held in the Khizāna—testimony to the care that was taken with books, even in times of conflict, and at the same time an example of the documentary evidence available for the rich and multifaceted history of Yemen’s book and library culture, whose story still needs to be written. The fate of other parts of the library of the Āl al-Wazīr remains unknown; a significant portion of the family’s books is said to have ended up in Istanbul.3 Most of what had remained with the family was confiscated and transferred to the Great Mosque after the failed coup d’état in 1948, in which members of the Āl al-Wazīr played a leading role.4

Among the largest collections that were incorporated into the Khizāna are the libraries of members of the Qāsimī family, which ruled the country for most of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These members include two grandsons of al-Imam al-Mansur al-Qasim b. Muhammad (1559–1620), the eponymous founder of the dynasty—namely, al-Mahdi li-Din Allah Ahmad b. al-Hasan b. al-Qasim (1620–1681) (10 percent) and Ahmad’s older brother Muhammad b. al-Hasan b. al-Qasim (1601–1668), whose private library stands out for its size (31 percent). Some of the leading bureaucrats during the first century of the Qāsimī period (sixteenth century) also had substantial personal libraries, the remains of which were likewise transferred to the Khizāna (21 percent). Imam Yahya also contributed a significant portion of manuscripts from his personal library to the newly founded Khizāna (17 percent).

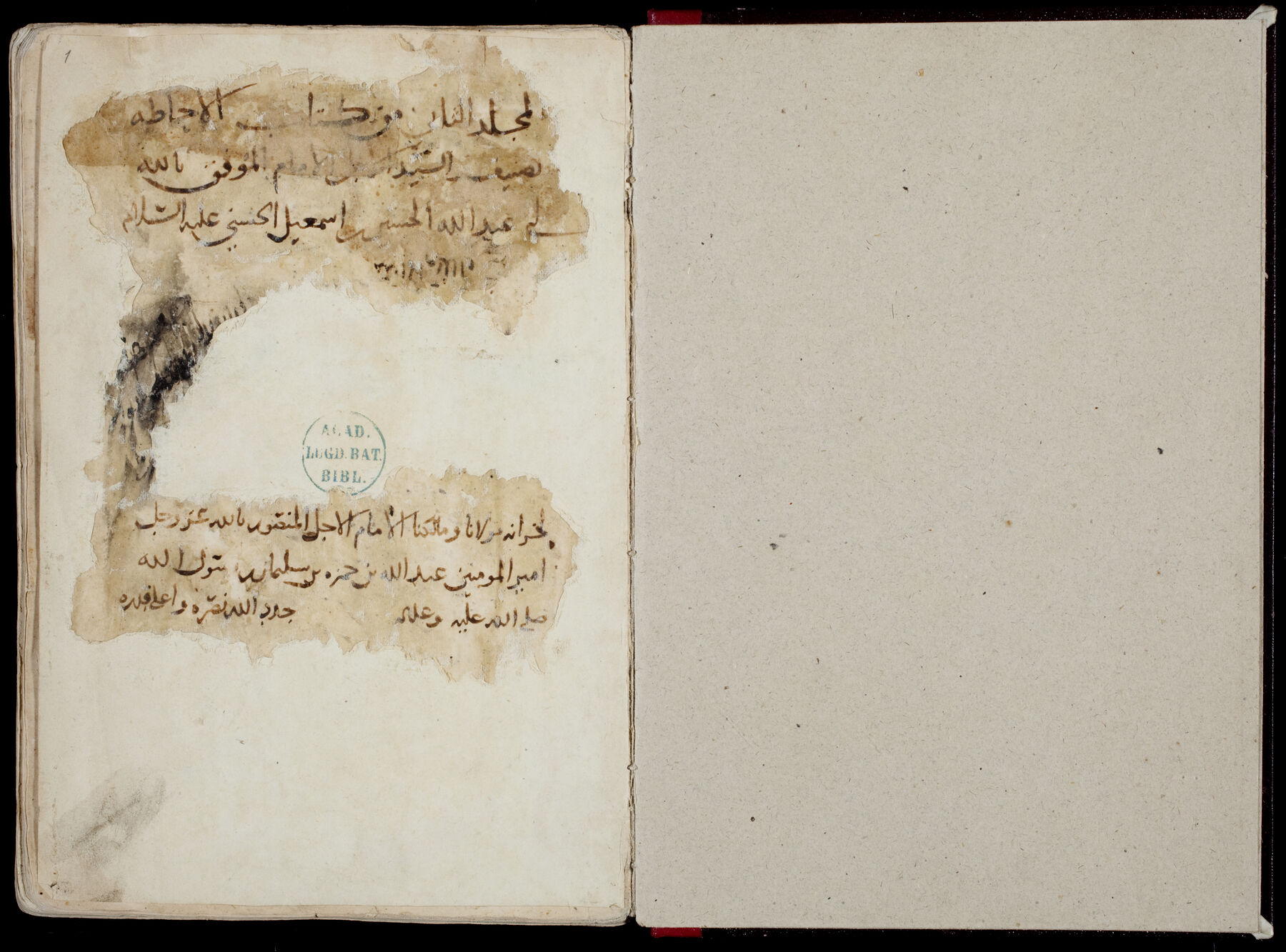

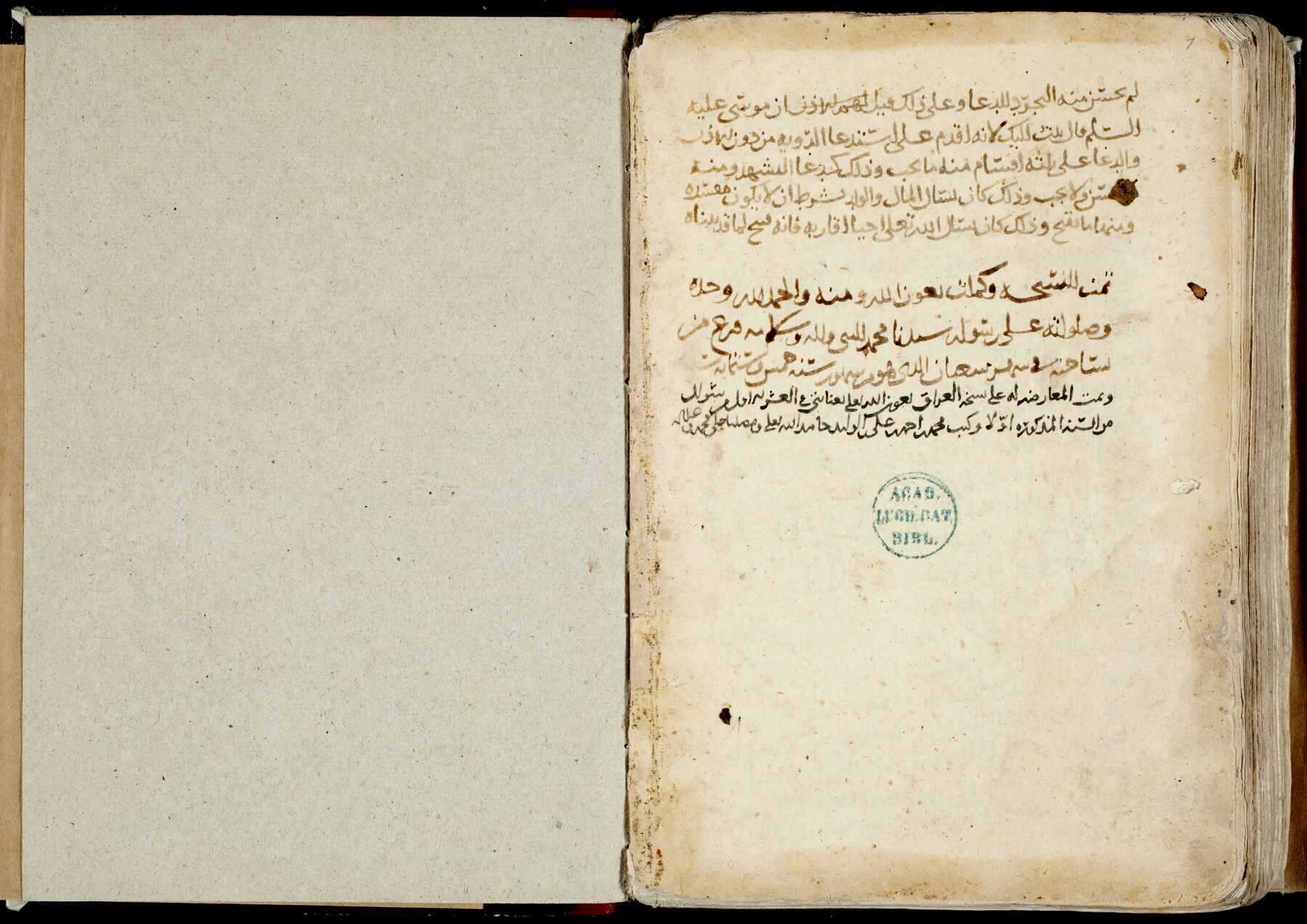

The imam’s concern to salvage what remained of the historical libraries to prevent further losses was certainly justified. Prior to the 1925 decree, numerous codices that had originally belonged to the library of Imam al-Mansur bi-llāh ʿAbd Allah b. Hamza, as well as those libraries founded by members of the Qāsimī dynasty, had been sold and are nowadays preserved in the libraries of Riyadh, Istanbul, Berlin, Leiden, Milan, Vienna, Munich, London, and even Benghazi (figs. 13.3a, 13.3b).5 Others are today in the possession of private owners in Yemen.

Figure 13.3a

Figure 13.3a Figure 13.3b

Figure 13.3bThe entries in the catalogue are classified according to twenty-six disciplinary headings,6 and within each section the titles are arranged in alphabetical order, with printed books and manuscripts listed side by side. While the classification system, as well as other organizational principles applied in the Khizāna, emulated notions of rudimentary library science at the time of its founding, it also reflects the traditional canon of mainstream Zaydism. Remarkably, several disciplines remain uncovered in the catalogue. There are no headings covering philosophy or Sufism, two strands of thought that were not cherished among the Zaydis. That the exclusion was the result of a conscious decision is corroborated by oral reports, according to which Imam Yahya gave special orders to exclude from the catalogue all categories of holdings that he considered inappropriate or harmful.7 That works of philosophy did circulate among the Zaydis of Yemen is, however, attested since the twelfth century. The two prominent twelfth-century scholars Qadi Jaʿfar b. Ahmad b. ʿAbd al-Salam al-Buhluli (d. 1177/78) and al-Hasan b. Muhammad al-Rassas (d. 1188), for example, wrote refutations of selected notions of the philosophers, and their respective works testify to their familiarity with some of the relevant primary sources, including perhaps al-Ghazali’s Doctrines of the Philosophers (Maqāṣid al-falāsifa).8 Moreover, a handwritten inventory of the library of Imam al-Mutawakkil Sharaf al-Din Yahya (d. 1558), a grandson of the renowned Imam al-Mahdi Ahmad b. Yahya b. al-Murtada (d. 1437) and a prominent scholar in his own right, includes a number of philosophical titles, such as two copies of Doctrines of the Philosophers, a book on logic by al-Farabi, and a partial copy of Avicenna’s Deliverance (K. al-Najāt). Imam Yahya is also reported to have captured significant quantities of books during his battles against the Ismaʿilis in Yemen, including an entire library of four hundred codices that he received as booty in May–June 1905.9 None of these works are listed in the catalogue, as they were kept during Imam Yahya’s lifetime in his personal library.10 Their later fate and current whereabouts are unknown. Ismaʿili missionary propagation (daʿwa) had been associated with Yemen since the end of the ninth century—that is, since about the time when Imam al-Hadi ila l-Haqq Yahya b. al-Husayn (d. 911) and his followers arrived in Ṣaʿda and established a Zaydi state in the northern highlands of Yemen, and the Ismaʿīlīs posed a serious threat to the Zaydis during the Ṣulayḥīd rule over Yemen, which lasted from about the mid-eleventh to the mid-twelfth century. Thereafter, the Ismaʿīlī daʿwa moved eastward toward India, although the community continued to be present in small numbers in Yemen. Sufism was also largely detested by the Zaydis,11 and historical accounts from the Qāsimī era regularly mention repeated attempts to purge the book markets of Sufi works, an indication that such titles did circulate among the Zaydis.

That works pertaining to philosophy, Sufism, and Ismāʿīlism are largely missing from the catalogue suggests that Imam Yahya asked them to be left uncatalogued. The 1942/43 catalogue thus testifies both to the long library tradition of Zaydi Yemen and to the continuous efforts to cleanse the curriculum through censorship and destruction and to control the literary canon (fig. 13.4).

Figure 13.4

Figure 13.4A Millennium of Zaydi Presence in Yemen

Since the ninth century, the Zaydi community has flourished mainly in two regions, the mountainous northern highlands of Yemen and the Caspian region of northern Iran. Over the following centuries, the Zaydis of Yemen remained largely isolated from their coreligionists in Iran as a result of their geographical remoteness and political seclusion. Unlike Yemen, northern Iran was in close proximity to some of the vibrant intellectual centers of the Islamic world between the ninth and eleventh centuries, and Iranian Zaydis were actively involved in the ongoing discussions. The most important among the period’s intellectual strands was the Muʿtazila, a school of thought that attributed primary importance to reason in matters of doctrine and that thrived under the Buyids, who ruled over Iran and Iraq. During the tenth century, Abu ʿAbd Allah al-Basri (d. 980), who was based in Baghdad, was at the helm of the Bahshamite branch of the movement, and his students included the two brothers and later Zaydi imams Abu l-Husayn Ahmad b. al-Husayn (Imam al-Muʾayyad bi-llah, d. 1020) and Abu Talib Yahya b. al-Husayn (Imam al-Natiq bi-l-Haqq, d. circa 1033), both prolific scholars. Abu ʿAbd Allah al-Basri’s successor as the head of the school was ʿAbd al-Jabbar al-Hamadhani (d. 1025). The latter enjoyed the patronage of the Buyid vizier al-SṢahib b. ʿAbbad, who appointed him chief judge in Rayy (today part of Tehran). ʿAbd al-Jabbar also had a fair number of Zaydis among his students, some of whom wrote commentaries on his theological works and composed their own books. Rayy continued to be a center of Zaydi Muʿtazili scholarship, even after the demise of ʿAbd al-Jabbar, and we know of a number of prominent Zaydi scholarly families in the city that flourished during the eleventh and early twelfth centuries.12

A rapprochement between the Zaydi communities in Iran and Yemen began in the early twelfth century and eventually resulted in their political unification. This development was accompanied by a transfer of knowledge from northern Iran to Yemen that comprised nearly the entire literary and religious legacy of Caspian Zaydism. The sources—chains of transmission and scribal colophons in manuscript codices, correspondence, and biographical literature, as well as biobibliographies and other historical works—provide detailed information about the mechanisms of this process. Throughout the twelfth century various prolific Zaydi scholars from the Caspian region were invited to come to Yemen: they brought numerous books by Iranian authors and acted as teachers to the Yemeni Zaydi community’s spiritual and political leaders, the imams, and other scholars in Yemen. At the same time, Zaydi scholars traveled from Yemen to Iran and Iraq for the purpose of study. The knowledge transfer reached its peak during the reign of the aforementioned Imam al-Mansur bi-llāh ʿAbd Allah b. Hamza. The imam founded a library in Ẓafār, his town of residence, for which he had a wealth of textual sources copied by a team of scholars and scribes.13

The imported Basran Muʿtazili literature from Iran served as an ideological backbone in the intra-Zaydi conflict with the local movement of the Muṭarrifiyya, a school of thought within Yemeni Zaydism that had evolved over the tenth and eleventh centuries and is named after Mutarrif b. Shihab b. ʿAmir b. ʿAbbad al-Shihabi (d. after 1067), who played a major role in formulating and systematizing its doctrines. Although the followers of the Muṭarrifiyya claimed to cling fervently to the theological teachings of the aforementioned al-Hadi ila l-Haqq and his sons, they developed a cosmology and natural philosophy of their own. They maintained, for example, that God had created the world out of three or four elements—namely, water, air, wind, and fire—and that it is through the interaction of these constituents of the physical world that change occurs; in other words, they endorsed natural causality rather than God’s directly acting upon his creation.

The precise contours of their doctrines cannot be restored at this stage. The conflict between the local Zaydi-Muṭarrifi faction and those Zaydis who adhered to the Bahshamite Muʿtazilite doctrine of northern Iran reached its peak during the reign of Imam al-Mansur bi-llāh ʿAbd Allah b. Hamza, an ardent adherent of the Bahshamite doctrines. He led a relentless, all-out war against the adherents of the Muṭarrifiyya, demolished their abodes,14 schools, and libraries, and had their entire literary heritage destroyed. Today, we possess only a few original works by Muṭarrifi authors to inform us about the movement’s doctrine and its development over time. However, there is a plethora of anti-Muṭarrifi polemics written by mainstream Zaydi authors, a genre that continued to thrive for several centuries after the movement went extinct. These polemics can be used only with great caution as a source for the reconstruction of the thought of the Muṭarrifiyya.15

The next important phase of religio-cultural renewal among the Zaydis in Yemen occurred during the Qāsimī era in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Under the rule of the Qāsimīs, the Ottomans, who had conquered Yemen in 1517, were pushed from the country’s inland regions, and they eventually withdrew from their last foothold, the coastal town of Mocha, in 1636. Moreover, the Qāsimī imams expanded their territory beyond the traditional Zaydi areas, and during the reign of the third Qāsimī imam, al-Mutawakkil Ismaʿil (r. 1644–76), most of the country, including lower Yemen and the eastern stretch of Hadramawt, came under Zaydi rule (fig. 13.5).

Figure 13.5

Figure 13.5Economically, the first century of Qāsimī rule was also particularly prosperous, as Yemen maintained a monopoly on the cultivation and export of coffee from 1636 through 1726. The Qāsimī imams, as well as other members of their family, were engaged in fostering a religious and cultural renewal of Zaydism and sought to spread it beyond its traditional boundaries into the newly conquered regions of Yemen, and the prosperity of the period provided them with the material means to do so. There was a significant rise in the production of manuscripts, and many members of the Qāsimī royal family as well as other leading dignitaries and scholars founded new libraries and accumulated significant collections of books, many of which were also imported from other parts of the Islamic world through the Sunni Shafiʿi regions of Yemen as well as through Mecca, which since the beginning of Islam had been an important center for the exchange of books and scholarship during the annual hajj period. At the same time, the Qāsimīs not only promoted scholarship but also carried out censorship by excluding from the canon works that they considered to contravene core Zaydi beliefs and doctrine—most importantly Sufi literature, as well as philosophy and Ismaʿīlī works. Under Qāsimī rule, the confiscation of property and libraries was a common means of combating political enemies within the Zaydi community.16

Beyond the Khizāna al-Mutawakkiliyya

The preservation of books, alongside confiscation, censorship, and occasional destruction of books and entire libraries, has continued in Yemen throughout the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first century. In the aftermath of the 1962 revolution and the resulting civil war, thousands of manuscripts from members of the former royal family, from some members of the family of the Prophet Muhammad (sadat), and from collections that were found in combat areas were confiscated and stored in the Maktaba al-Gharbiyya and later in the Dār al-Makhṭūṭāt in Sana’a (fig. 13.6). The latter’s holdings were repeatedly catalogued, though it remains uncertain what percentage of the entire collection (which grows continuously through confiscations by state authorities and chance finds) has so far been described.17

Additionally, only some of the former rulers’ libraries were integrated into the Khizāna al-Mutawakkiliyya under Imam Yahya’s rule. Since the Zaydi imams typically made an individual choice regarding where to establish their residences, the holdings of the various rulers’ libraries are dispersed all over the country. For example, none of the numerous extant precious manuscripts of the writings of Imam al-Muʾayyad bi-llah Yahya b. Hamza (1270–1348/49) in his own hand can be found today in the Khizāna al-Mutawakkiliyya. Of his major theological summa, the K. al-Shāmil li-ḥaqāʾiq al-adilla al-ʿaqliyya wa-uṣūl al-masāʾil al-dīniyya, a work in four volumes, autographs (actual manuscripts written by the original author) of volumes two and four are preserved in Taʿizz and Leiden, respectively. Further, many of the former holdings of the personal library of the aforementioned Imam al-Mutawakkil ʿala llah Sharaf al-Din Yahya are today kept in the library of the Grand Mosque of Dhamar. Only a fraction of such smaller libraries across the country, including countless family libraries, have been catalogued.18

Figure 13.6

Figure 13.6The socioreligious and cultural value of the Zaydi literary heritage as preserved in books and libraries for northern Yemen and its people can hardly be overestimated. The principal reason for its importance is the Zaydi notion of political authority, the imamate. Although the Zaydis restricted the privilege to claim the imamate to members of the family of Muhammad, the ahl al-bayt (preferably descendants of al-Hasan and al-Husayn), they do not insist on a hereditary line of imams. Among the qualifications required of a Zaydi imam, excellent knowledge in religious matters and the capacity to perform ijtihad (independent reasoning in legal matters) held top priority. As a result, the Zaydi imams were not only patrons of culture but also prolific scholars themselves, so a significant portion of the Zaydi literary legacy consists of the writings of the imams. Books and libraries therefore qualify as the principal identity marker for Zaydis of Yemen, and this also accounts for the millennium of nearly uninterrupted library history in the country’s highlands. The significance of books and libraries in Yemen is also the motivation behind the efforts of private Yemeni nongovernmental organizations and other institutions such as the Imam Zayd b. Ali Cultural Foundation and Markaz al-Badr al-ʿilmi wa-l-thaqafi, which both endeavor to make works by Zaydi imams and scholars available through publication and to digitize private book collections (fig. 13.7).

Figure 13.7

Figure 13.7At the same time, there are several factors that put the library tradition of Yemen at immediate risk today. As elsewhere, books are a commodity in Yemen, and the buying and selling of books and the dispersal of entire libraries following the demise of their owners are common occurrences. Moreover, manuscript culture has persisted in Yemen beyond the turn of the twenty-first century, as is evident from the fact that manuscripts are still being produced in large numbers. As a result, there are interesting encounters between manuscript tradition and technology. Once photocopy machines became available in Yemen, owners of manuscript libraries began to produce copies of individual codices from their collections and often had them bound in the traditional manner. These mechanically produced “new” codices became a novel commodity alongside codices produced by hand, and the same applies to compact discs and other digital media containing scans of large numbers of manuscripts, and often entire libraries, with poor or no documentation as to the provenance of the material and the whereabouts of the physical codices (fig. 13.8).19

Figure 13.8

Figure 13.8All this, together with the lack of catalogues for the majority of the numerous public and private libraries in Yemen, makes it impossible to prevent illicit traffic in manuscripts.20 Throughout much of the second half of the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first, Yemeni authorities have been constantly fighting manuscript dealers, trying to prevent them from smuggling manuscripts out of the country, apparently with only limited success.21 That such trade continues on a regular basis is attested to by the numerous collections of Yemeni manuscripts offered to libraries in the West during the second half of the twentieth century and occasional reports on social media of manuscripts of Yemeni provenance showing up in museums and private collections in the Persian Gulf region. Another development that has put significant portions of the Zaydi literary tradition at risk is the growing “sunnification” of Zaydism, a trend whose beginnings can be traced back to the fourteenth century. The towering figure in this endeavor was the eighteenth-century Yemeni scholar Muhammad b. ʿAli al-Shawkani (1760–1834), who sought to eliminate the Zaydi-Hādawī tradition—“Hādawī” referring to the founder of the Zaydi state in Yemen, al-Hadi ila l-Haqq—and accordingly revised the traditional works to be included in the curriculum. His program had little impact on the curriculum of the Zaydi elite of Yemen before the revolution, but the situation has changed dramatically since the official abolition of the imamate in 1962. This plus the increasing presence of the so-called maʿahid al-ʿilmiyya (Sunni teaching institutions with a distinct anti-Hādawī bias that have spread in Yemen since 1972 with Saudi backing) constitute a major threat to the countless smaller public and private libraries in the country. Many of the private libraries in the north of Yemen were severely damaged, looted, or even destroyed over the course of the twentieth century as a result of political turmoil and wars, and the continuing war today constitutes another imminent threat not only to the local population but also to the cultural heritage of the country, including its many libraries (fig. 13.9).

Figure 13.9

Figure 13.9Conclusion

For Yemen’s book culture, it is a curse and a blessing that some of the most precious collections were purchased by European, Ottoman Turkish, and Saudi scholars, diplomats, merchants, and travelers during the second half of the nineteenth and the early decades of the twentieth century (and beyond); these manuscripts, numbering between ten and twenty thousand, are nowadays housed in libraries outside of the country. Within Europe, the Glaser collections (today in Berlin, Vienna, and London) and the Caprotti collections (in Munich and Milan) as well as other, smaller collections have served as the basis for Western scholarship on Zaydism since the early twentieth century. Whereas the collections of manuscripts of Yemeni provenance in Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other countries in the Middle East remain largely unexplored and often even uncatalogued, the majority of European libraries with substantial holdings of Yemeni provenance subscribe to the concept of digital repatriation of those treasures by making their material available through open access, in most cases both through their own digital repositories and under the auspices of collaborative projects such as the Zaydi Manuscript Tradition project.22 At the same time, the history of libraries in Yemen is largely terra incognita, and no attempt has ever been made to write a critical account of the historical or present-day libraries of Yemen.23 In view of the lack of a critical mass of reliable catalogues, it is the codices themselves that constitute the most important sources on the historical libraries of Yemen: many contain ample documentary materials, such as ownership statements, purchase notes, scribes’ colophons, study notes, and often entire inventories of historical libraries. An analysis of a critical mass of codices could contribute to reconstructing the holdings of individual libraries and their fate over time, which in turn would help curb illicit trafficking and allow for collaborative efforts among scholars in Yemen, the wider Middle East, and beyond to salvage and study the Zaydi Yemeni manuscript tradition. None of this is possible under current circumstances.

Biography

- Sabine SchmidtkeSabine Schmidtke is professor of Islamic intellectual history in the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. Her research interests include Shiʿism (Zaydism and Twelver Shiʿism), intersections of Jewish and Muslim intellectual history, the Arabic Bible, the history of Orientalism and the Science of Judaism, and the history of the book and libraries in the Islamicate world. Her recent publications include Muslim Perceptions and Receptions of the Bible: Texts and Studies (2019), with Camilla Adang; Traditional Yemeni Scholarship amidst Political Turmoil and War: Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl b. al-Muṭahhar al-Manṣūr (1915–2016) and His Personal Library (2018); and The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Philosophy (2017), coedited with Khaled el-Rouayheb.

Suggested Readings

- Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, eds., Yemeni Manuscript Cultures in Peril (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2022).

- David Hollenberg, Christoph Rauch, and Sabine Schmidtke, eds., The Yemeni Manuscript Tradition (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2015).

- Brinkley Messick, Sharīʿa Scripts: A Historical Anthropology (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

- Sabine Schmidtke, Traditional Yemeni Scholarship amidst Political Turmoil and War: Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl b. al-Muṭahhar al-Manṣūr (1915–2016) and His Personal Library (Córdoba: Córdoba University Press, 2018).

- Nancy Um, “Yemeni Manuscripts Online: Digitization in an Age of War and Loss,” Manuscript Studies 5, no. 1 (2021), https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims/vol5/iss1/1.

Notes

Fihrist kutub al-Khizāna al-mutawakkiliyya al-ʿāmira bi-l-Jāmiʿ al-muqaddas bi-Ṣanʿāʾ al-maḥmiyya (Sana’a: Wizārat al-maʿārif, 1942/43). ↩︎

In 1984, another catalogue, describing only the manuscripts of the former al-Khizāna al-Mutawakkiliyya, nowadays Maktabat al-Awqāf, was published: Aḥmad ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ruqayḥī et al., Fihrist makhṭūṭāt maktabat al-Jāmiʿ al-kabīr, Ṣanʿā, 4 vols. (Sana’a: Wizārat al-awqāf wa-l-irshād, 1984). As in the 1942/43 catalogue, the provenance of the individual codices is again indicated, though the information provided seems less reliable overall. ↩︎

See Zaid bin Ali al-Wazir, “The Historic Journey of Banī al-Wazīr’s Library,” in Yemeni Manuscript Cultures in Peril, ed. Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2022). ↩︎

What is left of the library of another branch of the family is kept today in Hijrat al-Sirr, inaccessible to outsiders. For a partial handlist of the library’s holdings, see ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī, Fihris makhṭūṭāt baʿḍ al-maktabāt al-khāṣṣa fī al-Yaman (London: Furqan Foundation, 1994). For the fate of the Āl al-Wazīr during the twentieth century, see Gabriele vom Bruck, Mirrored Loss: A Yemeni Woman’s Life Story (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019). ↩︎

See, e.g., Anne Regourd, “Note sur Aḫbār al-Zaydiyya bi-al-Yaman et autres oeuvres du muṭarrifite al-Laḥǧī,” Nouvelles Chroniques du manuscrit au Yémen, no. 11 (July 2020): 131–46. ↩︎

These include Qurʾanic sciences, exegesis, prophetic traditions, dogmatics, inward sciences and ethics, logic and disputation, legal theory, Hādawī law, Sunni law, law of inheritance, grammar, morphology, eloquence, linguistics, poetry and literature, history, medicine, dream interpretation, astronomy, and agriculture. ↩︎

At present, efforts are underway in Yemen to produce a new catalogue of the holdings of the Maktabat al-Awqāf to include the so-far-uncatalogued manuscripts. ↩︎

See Hassan Ansari, “Al-Barāhīn al-Ẓāhira al-Jaliyya ʿalā anna l-Wujūd Zāʾid ʿalā l-Māhiyya by Ḥusām al-Dīn Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad al-Raṣṣāṣ,” in A Common Rationality: Muʿtazilism in Islam and Judaism, ed. Camilla Adang, Sabine Schmidtke, and David Sklare (Würzburg, Germany: Ergon, 2007), 337–48; and Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, “Sixth/Twelfth-Century Zaydī Theologians of Yemen Debating Avicennan Philosophy,” Shii Studies Review 5 (2021): 219–71. ↩︎

See Eugenio Griffini, “Die jüngste ambrosianische Sammlung arabischer Handschriften,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 69, no. 1–2 (1915): 80. See also Ismail K. Poonawala, “Ismāʿīlī Manuscripts from Yemen,” Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 5, no. 2–3 (2014): 220–45. ↩︎

Rudolf Strothmann, ed., Gnosis-Texte der Ismailiten: Arabische Handschrift Ambrosiana H 75 (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1943), 10–11. ↩︎

Wilferd Madelung, “Zaydi Attitudes to Sufism,” in Islamic Mysticism Contested: Thirteen Centuries of Controversies and Polemics, ed. Frederick de Jong and Bernd Radtke (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 1999), 124–44. ↩︎

For an overview of Iranian Zaydism and the reception of Muʿtazilism, see Hassan Ansari, “The Shīʿī Reception of Muʿtazilism (I): Zaydīs,” in The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Theology, ed. Sabine Schmidtke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 181–95. ↩︎

See Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, Studies in Medieval Islamic Intellectual Traditions (Atlanta: Lockwood Press, 2017), 115–40. ↩︎

For the Yemeni hijra, see Wilferd Madelung, “The Origins of the Yemenite Hijra,” in Arabicus Felix: Luminosus Britannicus; Essays in Honour of AFL Beeston on His Eightieth Birthday, ed. Alan Jones (Reading, UK: Ithaca Press, 1991), 25–44. ↩︎

For details on the reception of Bahshamite doctrine among the Zaydis of Yemen and the conflict with the Muṭarrifiyya, see Hassan Ansari, Sabine Schmidtke, and Jan Thiele, “Zaydī Theology in Yemen,” in The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Theology, ed. Schmidtke, 473–93. ↩︎

For the history of Yemen under the Qāsimīs, see Tomislav Klarić, “Untersuchungen zur politischen Geschichte der qāsimidischen Dynastie [11./17. Jh.],” PhD diss., University of Göttingen, 2007; and Nancy Um, “1636 and 1726: Yemen after the First Ottoman Era,” in Asia Inside Out, ed. Eric Tagliacozzo, Helen F. Siu, and Peter C. Perdue (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 112–34. ↩︎

For details, see Sabine Schmidtke, “Preserving, Studying, and Democratizing Access to the World Heritage of Islamic Manuscripts: The Zaydī Tradition,” Chroniques du manuscrit au Yémen 23, no. 4 (2017): 103–66. ↩︎

For details, see Schmidtke, “Preserving, Studying, and Democratizing Access.” ↩︎

This is also the case with the online digital Imam Zayd b. Ali Cultural Foundation Library, which contains most of the material previously distributed by the foundation on compact discs and now kept on a website run by the Ministry of Endowments & Religious Affairs of Oman: see Ministry of Endowments & Religious Affairs, “Cultural Foundation Library,” https://elibrary.mara.gov.om/mktbtt-muosstt-aliemam-zed-bn-ale-althqafett/mktbtt-muosstt-aliemam-zed-bn-ale-althqafett/. ↩︎

By way of example, see Sabine Schmidtke, “The Intricacies of Capturing the Holdings of a Mosque Library in Yemen: The Library of the Shrine of Imām al-Hādī, Ṣaʿda,” Manuscript Studies 3, no. 1 (2019): 220–37; and Traditional Yemeni Scholarship amidst Political Turmoil and War: Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl b. al-Muṭahhar al-Manṣūr (1915–2016) and His Personal Library (Córdoba: Córdoba University Press, 2018). ↩︎

For examples, see Sabine Schmidtke, “The Zaydi Manuscript Tradition: Virtual Repatriation of Cultural Heritage,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 50, no. 1 (2018): 124–28. ↩︎

See Valentina Sagaria Rossi and Sabine Schmidtke, “The Zaydi Manuscript Tradition (ZMT) Project: Digitizing the Collections of Yemeni Manuscripts in Italian Libraries,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies (COMSt) Bulletin 5, no. 1 (2019): 43–60 (with further references). ↩︎

The forthcoming study by Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, Towards a History of Libraries in Yemen, covers only some aspects of this large field of inquiry. ↩︎