8. When Peace Is Defeat, Reconstruction Is Damage: “Rebuilding” Heritage in Post-conflict Sri Lanka and Afghanistan

- Kavita Singh

عندما يكون السلام هزيمة، تتضرر عملية إعادة الإعمار: "إعادة بناء" التراث في مرحلة ما بعد النزاع في سريلانكا وأفغانستان

كافيتا سينغ

عملية إعادة البناء الثقافية بعد النزاعات قد تتحول إلى أداة يمكن من خلالها للقوي أن يُعزز قبضته على البلاد ويعمّق تهميش الأقليات. تتم دراسة هذه الظاهرة هنا فيما يتعلق بكل من "جفنا" في سريلانكا و"باميان" في أفغانستان.

ملخص

تأخذ عملية إعادة البناء الثقافية في حقبة "ما بعد النزاع" في سريلانكا وأفغانستان مسارًا مثيرًا للقلق في المناطق التي تهيمن عليها أقليات دينية أو عرقية. يتم استقصاء هذا الأمر في سريلانكا بما يتعلق بشبه جزيرة جفنا في شمال البلاد التي تُعتبر موطن معظم التاميل الهندوس في البلاد، ووادي باميان في أفغانستان الذي تعيش فيه أقلية الهزارة الشيعية. في هذه الحالة، أصبحت عمليات إعادة البناء وترميم التراث – التي تهدف أصلًا إلى إصلاح الضرر في المجتمع – بمثابة أدوات يستمر من خلالها طرف واحد في الهيمنة على الآخر. ففي سريلانكا، تستخدم حكومة الأكثرية كافة الأدوات الموجودة في متناول يدها من أجل "استعادة" الإرث الذي يعزز تقويض أقلية التاميل. وفي أفغانستان، فإن المنظمات الدولية التي قَدِمت للمساعَدة عقب حقبة طالبان ساهمت – بغير قصد – في لعبة قوة دقيقة بين الحكومة المركزية وأقلية عرقية لطالما كانت على هامش الحياة الأفغانية.

不以和平为目的的重建就是毁灭:冲突后斯里兰卡与阿富汗的遗产“重建”

卡維塔·辛格 (Kavita Singh)

冲突后的文化重建可能会成为权势者巩固国家政权、加快少数民族边缘化的手段。本文以斯里兰卡贾夫纳与阿富汗巴米扬为例,对这一现象进行剖析。

摘要

斯里兰卡与阿富汗冲突后时期的文化重建工作在宗教或少数民族占主导地位的地区形成了令人不安的局面。在斯里兰卡贾夫纳半岛北部生活着全国信奉印度教的多数泰米尔人,而在阿富汗巴米扬山谷则居住着什叶派哈扎拉人。文章结合两地的情况,对这种局面进行探究。这些地区的重建与遗址保护本应以修复社会为目的,却成为一方持续统治另一方的工具。斯里兰卡的多数派政府试图利用一切工具“恢复”遗址,实则希望剥夺泰米尔少数民族的权力。而在阿富汗中央政府与长期处在国家生活边缘的少数民族争权夺势的过程中,在塔利班统治结束后前来支援的各个国际组织在无意间挑拨了二者之间微妙的关系。

Post-conflict cultural reconstruction can become a tool through which the powerful consolidate their hold over a country and deepen the marginalization of its minorities. This phenomenon is examined here in relation to Jaffna in Sri Lanka and Bamiyan in Afghanistan.

Abstract

Cultural reconstruction in the “post-conflict” period in Sri Lanka and Afghanistan has taken disturbing shape in regions dominated by religious or ethnic minorities. In Sri Lanka this is explored in relation to the northern Jaffna Peninsula, which is home to most of the country’s Hindu Tamils; in Afghanistan, the Bamiyan Valley, where the Hazara Shia minority lives. Here, the very processes of reconstruction and heritage conservation meant to repair a society become instruments through which one side continues its domination over the other. In Sri Lanka, a majoritarian government uses all the tools at its disposal to effect a “recovery” of heritage that underlines the disempowerment of the Tamil minority; and in Afghanistan the international organizations that have come to assist in the aftermath of the Taliban era unwittingly contribute to a subtler power play between the central government and an ethnic minority that has long been at the margins of Afghan life.

Lorsque la paix est une défaite, la reconstruction est un préjudice : la « restauration » du patrimoine au Sri Lanka et en Afghanistan après les conflits

Kavita Singh

La reconstruction culturelle après les conflits peut devenir un outil grâce auquel les puissants consolident leur main-mise sur un pays et aggravent la marginalisation de ses minorités. Ce phénomène est étudié ici relativement à Jaffna au Sri Lanka et à Bâmiyân en Afghanistan.

Résumé

La reconstruction culturelle au cours de la période « post-conflit » au Sri Lanka et en Afghanistan a pris une forme troublante dans les régions dominées par des minorités religieuses ou ethniques. L’étude s’intéresse au Sri Lanka dans la péninsule septentrionale de Jaffna où résident la plupart des Tamouls hindous du pays, puis à l’Afghanistan dans la vallée de Bâmiyân où vit la minorité chiite hazara. Dans ces cas-ci, les processus mêmes de reconstruction et de conservation du patrimoine destinés à réparer une société deviennent des instruments grâce auxquels une partie maintient sa domination sur l’autre. Au Sri Lanka, un gouvernement majoritaire a recours à tous les outils à sa disposition pour mener à bien une « restauration » du patrimoine qui souligne l’asservissement de la minorité tamoule. En Afghanistan, les organisations internationales venues apporter une assistance à la suite de l’ère des Talibans contribuent à leur insu à un jeu de pouvoir plus subtil entre le gouvernement central et une minorité ethnique repoussée de longue date sur les marges de la société afghane.

Когда мир – результат поражения, восстановление оборачивается разрушением. «Возрождение» культурного наследия в постконфликтных Шри-Ланке и Афганистане

Кавита Сингх

Постконфликтное культурное восстановление может превратиться в инструмент, посредством которого власти укрепляют свои позиции и усиливают маргинализацию меньшинств. Этот феномен исследуется в данной главе на примере Джафны в Шри-Ланке и Бамиана в Афганистане.

Краткое содержание

Культурное восстановление в так называемый постконфликтный период в Шри-Ланке и Афганистане приняло вызывающие серьезное беспокойство формы в регионах, оказавшихся под властью религиозных или этнических меньшинств. В Шри-Ланке этот феномен исследуется в отношении северного полуострова Джафна, где проживает большинство тамильского населения страны; в Афганистане - в отношении долины Бамиан, население которой составляет этническое меньшинство хазарейцев-шиитов. Здесь сам процесс восстановления и сохранения культурного наследия, направленный на залечивание социальных ран, превратился в инструмент, посредством которого одна сторона продолжает доминировать над другой. В Шри-Ланке мажоритарное правительство использует все доступные инструменты для «восстановления» наследия, вследствие которого отчуждение тамильского меньшинства лишь усиливается. В Афганистане международные организации, поддерживающие страну в пост-талибанскую эру, невольно способствуют тонкой игре между центральным правительством и этническим меньшинством, которое в течение длительного времени находилось на окраине социальной жизни Афганистана.

Cuando la paz es derrota, la reconstrucción es daño: la “reconstrucción” del patrimonio en Sri Lanka y Afganistán tras el conflicto

Kavita Singh

La reconstrucción cultural tras un conflicto puede convertirse en una herramienta a través de la cual quienes ostentan el poder consolidan su dominio sobre un país y profundizan la marginalización de sus minorías. Este fenómeno se analiza aquí en relación con Jaffna en Sri Lanka y Bamiyán en Afganistán.

Resumen

La reconstrucción cultural en el período “posconflicto” en Sri Lanka y Afganistán ha adoptado una forma perturbadora en regiones dominadas por minorías religiosas o étnicas. En Sri Lanka, ello se explora en relación con la península de Jaffna al norte de la isla, donde residen la mayoría de los tamiles hinduistas del país; en Afganistán, el valle de Bamiyán, donde habita la minoría hazara chiita. Aquí, los mismos procesos de reconstrucción y conservación del patrimonio que se supone deben reparar una sociedad se convierten en instrumentos a través de los cuales un bando perpetúa su dominación sobre el otro. En Sri Lanka, un gobierno mayoritario hace uso de todas las herramientas a su disposición para efectuar una “recuperación” del patrimonio que subraya el desempoderamiento de la minoría tamil; en Afganistán, las organizaciones internacionales que han acudido a asistir tras la era de los talibanes contribuyen inconscientemente a un juego de poderes más sutil entre el gobierno central y una minoría étnica que lleva mucho tiempo en los márgenes de la vida afgana.

In the 2000s, two countries near my home in India emerged from a long and brutal period of internal conflict. With the ouster of the Taliban in 2001 and the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in 2009, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka seemed ready to leave their turbulent pasts behind and enter an era of greater peace. But the quiet that descended on these lands came with victory for one side and defeat for another. What does “peace” look like in these circumstances, when a community of winners and a community of losers must live in a nation side by side? As countries riven by civil war or internecine conflicts head into what looks like their “post-conflict” periods, what appears to be peace to one group may look very much like subjugation to the other. In these contexts, even acts of rebuilding and repair can become instruments for the humiliation of the losing side.

This chapter examines the disturbing shape taken by cultural reconstruction in the post-conflict period in regions with predominant religious or ethnic minorities: the northern Jaffna Peninsula in Sri Lanka, home to most of the country’s Hindu Tamils; and the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan, inhabited by the Hazaras, a Shia minority. In both these cases, we will see how the very processes of reconstruction and heritage conservation, meant to repair a society, can become instruments through which one side continues its domination over the other. In Sri Lanka a majoritarian government has used all the tools at its disposal to effect a “recovery” of heritage that underlines the disempowerment of the Tamil minority; and in Afghanistan the international organizations that have come to assist in the aftermath of the Taliban era have unwittingly contributed to a subtler power play between the central government and an ethnic minority that has long been at the margins of Afghan life.

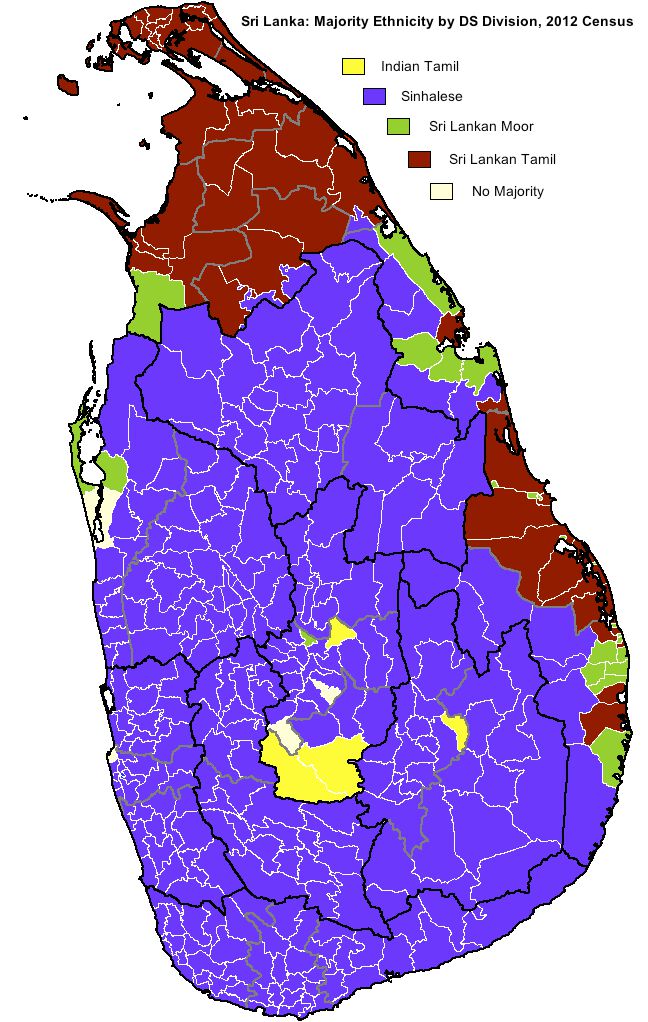

Vanquished Tamils and Militant Monks: Inside Sri Lanka’s Troubled Peace

In 2009 Sri Lanka’s bitter civil war came to a brutal end. As a violent conflict that had cost the lives of more than a hundred and fifty thousand Sri Lankans, displaced an estimated three hundred thousand, and laid waste to the Northern and Eastern Provinces, the civil war had raged for over twenty-six years. The roots of the conflict lay in the majoritarian policies adopted by the Sri Lankan government immediately after independence from British colonial rule in 1948. Dominated by the Buddhist Sinhalas, who constituted approximately 70 percent of the population, the Sri Lankan parliament enacted laws that discriminated against minorities, the largest number of which were Tamils, a Hindu community descended from workers brought from South India to labor on colonial plantations. The Tamils who constituted approximately 11 percent of the Sri Lankan population found themselves disenfranchised. Minor conflicts between Sinhalas and the Tamils often turned into pogroms against the latter, overtly or covertly supported by the state. By the 1970s a militant Tamil resistance took shape, and within a decade there were organized Tamil militias demanding a sovereign Tamil state. Most prominent among these was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which developed territorial, airborne, and naval units and made formidable use of suicide attacks.1 The years that followed saw a full-blown civil war of incredible brutality on both sides. Tamil insurgents managed to control large parts of the Northern and Eastern Provinces for years at a time and successfully targeted prominent Sinhala figures, including former heads of state. The Sri Lankan forces responded with great ferocity. In a war that lasted two and a half decades, both sides were accused of all manner of war crimes. Several rounds of peace talks failed, and the war eventually came to an end when the Tamil forces were comprehensively defeated by the Sri Lankan army.

For the Tamils of Sri Lanka, the end of the war has brought a bitter peace that has only sharpened the discrimination that had sparked the unrest in the first place. Everywhere in the Tamil-majority Northern and Eastern Provinces, the military is an inescapable presence; in some areas, there is one soldier for every three civilians. The military has expropriated approximately one-third of the land in these regions; military camps do not just occupy farmlands and homes that once belonged to Tamils but have been deliberately built over graveyards and memorial sites for the fallen soldiers and leaders of the Tamil side, denying Tamils the right to remember and mourn their dead. The redevelopment work is touted by the Sri Lankan government as one of the great features of the “New Dawn,” an era of reconstruction and repair promised by the government after the end of the civil war. The government’s projects, however, are seen to selectively benefit the Sinhalas, who are being brought to these provinces to alter the demography while Tamils continue to live in resettlement camps. The state’s undeclared policy of Sinhalization also effaces the Tamil presence and rewrites the Tamil past. While the remembrance of the recent past is managed through the careful control of monuments, memorials, and commemorative practices relating to the civil war, the rewriting of the ancient past is accomplished by an ideologically motivated official archaeological establishment that works in close association with ultranationalist Sinhala Buddhist groups.

The Northern Province, the last stronghold of the LTTE, was for a long time cut off from the rest of the nation. As highways reopened and mobility was reestablished, the North became a popular tourist destination for Sinhala visitors from the South. Today this tourist itinerary includes Buddhist pilgrimage sites as well as a “dark tourism” circuit that includes ruins and battlegrounds where critical events of the civil war unfolded. In Kilinochchi, the de facto capital of the Tamil Eelam or Nation, visitors came to see the ruined home of the former LTTE leader Prabhakaran and the four-story underground bunker that served as his headquarters. On finding that the bunker’s elaborate construction elicited admiration from some visitors, it was blown up by the army in 2013. Now the major tourist site there is the War Hero Cenotaph, a public sculpture sponsored by the army that takes the shape of a concrete wall shattered by a giant concrete-piercing bullet—munitions that were critical to the army’s success in penetrating LTTE defenses—and surmounted by a lotus flower that suggests peace and regeneration in the aftermath of war (fig. 8.1).

The North of Sri Lanka is dotted with such monuments that advertise the new era in which the army’s control of the region is complete. Using an easy-to-read visual symbolism, these military-sponsored memorials are set in manicured complexes and are heavily guarded by soldiers. Dedicatory plaques at the memorial sites recall the “glorious” contribution of the military forces. Their inscriptions are written in Sinhala and English but not in Tamil, making clear their intended audiences.

State-sponsored war memorials are not the only structures that have new prominence in the northern landscape. “Travelling through the Tamil areas in North Sri Lanka, one is shocked to see the changing demography of the land,” journalist Amir Ali notes. “A land that was once inhabited by Tamils and a land that had a distinct flavor of Tamil culture and heritage is now in the grip of Sinhalese hegemony, seen in the form of Buddhist statues, viharas (Buddhist monasteries) and stupas (Buddhist funerary monuments) dotting the landscape that is also lined by broken Tamil homes and newly built shanties of Tamil refugees.”2 These Buddhist statues and buildings are clearly meant to alter the landscape and mark it with a Sinhala presence. They are often sponsored by Buddhist ultranationalist groups, who do their work under the protection of the army or the police.

What is even more concerning, and of greater interest, however, is the way the Tamil landscape is being Sinhalized not only through new accretions but also through a reinterpretation of old and ancient structures. Ancient Tamil sites are “discovered” to have been built over preexisting Buddhist structures, and all Buddhist structures are assumed to be Sinhalese. The presumed “priority” of Sinhala presence then justifies the removal of Tamil traces. The government’s Department of Archaeology seems to be fully complicit in this project of overwriting the Tamil past.

To produce a purely Sinhala primordial past, archaeologists have to contend with a history that is complex and interwoven. While Sinhalas would like to project themselves as the oldest inhabitants of Sri Lanka, seeing Tamils as recent migrants who came during the colonial period, in fact Tamils were present on the island in ancient times. The Chola dynasty from nearby Tamil Nadu in India extended its empire to Sri Lankan island territories in the tenth century. Its legacy includes a number of temples and sculptures in classical Chola style that remain in Sri Lanka.

Even before the civil war, the archaeological wealth left by this contact was downplayed. Ancient monuments built by Tamil rulers were left out of a prominent UNESCO-sponsored heritage site development program, and excavations were simply not undertaken in areas that could have yielded rich finds related to the ancient Tamil presence.3

Since the war, the long neglect of Tamil and other non-Sinhala sites is being replaced with a new kind of intense attention. As mentioned, historical sites associated with Tamils are being analyzed afresh and are “discovered” to have had a Buddhist substratum that predates Tamil settlements. The evidence of Buddhist settlements is seen as delegitimizing the Tamil presence, despite the fact that in ancient times many Tamils too were adherents of Buddhism, and that ancient monuments and sculptures can be simultaneously Tamil and Buddhist. These archaeological “finds” add to the Sinhala sense of grievance against Tamils by perpetuating the idea that everywhere and at all times, Tamils violently displaced Sinhalas, destroyed their property, and robbed them of their land. These “discoveries” are then instrumentalized in the present and often result in the dismantling of “later” buildings and the eviction of “illegitimate” users occupying the site. Of particular concern is the willingness of the official archaeological infrastructure to be used as a tool in this political project. Two of the many sites where these procedures are visible are examined here.

In the late twentieth century, archaeologists discovered a richly layered site at Kandarodai in the North of Sri Lanka. Some of the oldest remains were megalithic burials, possibly dating to the second millennium BCE. The burials closely resembled those found in South India, pointing to a shared culture across Tamil Nadu in India and northern Sri Lanka in the pre-Buddhist period. Later burials at the site were believed to be of the Buddhist period, but their construction was similar to that of the ancient megaliths, pointing to continuities in the local culture over a long period. A plaque depicting the goddess Lakshmi and many of the coins, pottery, and other objects found at deep levels of the site were inscribed in Tamil. Buddhist artifacts were found in shallower layers above the Tamil finds. The evidence, unearthed in a 1967 excavation carried out by the University of Pennsylvania, suggested that this was an ancient Tamil and perhaps a Tamil-Buddhist site. But all of the Tamil-related evidence remained unpublished and ignored, while the Buddhist materials were widely publicized. At some point the Sri Lankan government’s Department of Archaeology built dagobas, Buddhist funerary monuments, upon the ancient circular stone foundations as a fanciful “reconstruction,” giving the site a markedly Buddhist appearance. Today, Kandarodai—whose name has been Sinhalized to Kadurugoda—has been placed under the care of a Sinhala monk and to the many southern Sri Lankan pilgrim-tourists who visit it the complex is projected as proof that Sinhala Buddhists formerly occupied the entire island before being displaced by Tamil intruders.4 A new signboard in Sinhala claims that excavations uncovered Buddha statues, painted tiles, and coins from the classical Sinhala kingdoms that date to at least eight hundred years after the earliest layers at the site. “This temple,” the signboard says, assuming that there was such a structure there, “was destroyed by the Dravida (South Indian) king Sangili who ruled in the 16th century.”5 Subliminally, the history of a sixteenth-century conquest of the North by a Tamil monarch is conflated with the insurgency of the LTTE, whose territory this once was, making the Tamils perpetually disruptive outsiders and making the current Sri Lankan government and Buddhist monastic orders the joint agents in whose pastoral care the land’s original identity is finally being safeguarded (fig. 8.2).

The process by which Kandarodai was transformed into a Sinhala-Buddhist site unfolded over decades. It was accomplished first through acts of omission (concealing inconvenient archaeological data) and then by acts of commission (building Buddhist-looking monuments in the name of restoration, placing the site under the care of a Buddhist monk) that have gathered pace over the years.

To see processes by which archaeology abets a Sinhala takeover of Tamil cultural spaces unfolding before us we can turn to Omanthai, a small village that once marked the southern edge of LTTE-held territories. Soon after the area was captured by the Sri Lankan army, a soldier planted a small Buddha statue on the premises of a Hindu temple in the village. Locals who agitated for the removal of the statue were threatened by the army, which put up signs stating that the Hindu temple had been built over an ancient Buddhist site. As the protests by local Tamils grew, the state intervened by sending archaeologists to investigate the site. The statue that caused the friction was itself a small mass-produced artifact of no historical importance, but the archaeologists reported that they had found other artifacts relating to the “Anuradhapura-Polonnaruwa period,” the fifth-to-tenth-century period that is the classical age of Sri Lankan Buddhist history. They also found stones with Sinhala inscriptions. “We do not know how these artifacts came to this site,” one of the archaeologists said, but indicated they would need further study.6 The archaeologists were given police protection for the duration of this visit, in which they found “proof” of prior Buddhist occupation. The presence of these artifacts, which mysteriously appeared thousands of kilometers away from the main centers of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, may well point to the ways in which archaeology—through its experts and artifacts—has been routinely pressed into service in Sri Lanka to produce the narratives of heritage that are most convenient for the ruling majority.

The cases studied by researchers thus far point to the worrying role of archaeology in Sri Lanka, which seems to be a willing tool in the hands of an ethnonationalist state. As Jude Fernando points out, “The fundamental issue is not with the country’s Sinhala Buddhist archaeological heritage . . . but rather with the function of Sinhala Buddhist heritage as [providing] the dominant national identity of the state that renders those who do not belong to that heritage as second-class citizens.”7 One might go further: given the way in which archaeology is summoned to provide proof of Sinhala claims to primordial status, which then allows Sinhalas to wrest sites away from the Tamil side, archaeology becomes akin to a military instrument of territorial expansion.

The nexus between archaeology, the ethnonationalist state, and the military was made even more blindingly obvious in 2020, when President Gotabaya Rajapaksa created a special archaeological task force for the survey and preservation of sites in Sri Lanka’s Eastern and Northern Provinces and incorporated it into the Ministry of Defence, to be headed by a military general. In Sri Lanka, it seems the overlap between the forces of knowledge production and the force of arms is now complete.

Buddhas and Lovers in Bamiyan: Layers of Meanings versus the “Authentic Original”

Whereas in Sri Lanka we see a Buddhist ethnonationalism using the state apparatuses of archaeology and restoration to rewrite the island nation’s history to suit majoritarian beliefs, in Afghanistan we see a Buddhist heritage that, instead of being foregrounded, seems to be suffering multiple erasures through both deliberate and unwitting deeds by many actors—the Taliban and the successor republican government as well as international agencies offering relief and aiding reconstruction.8

Afghanistan too has suffered greatly in the past half century. Its economy, society, and polity have been shattered by seemingly endless strife. The era of Taliban rule, from 1996 to 2001, was a particularly low point in its difficult history. This was a brutal government that committed countless atrocities against its own people while supporting the international terrorist organization al-Qaeda, which committed acts of terrorism abroad. The Taliban outlawed most kinds of music, art, and education for Afghans; even chess and soccer were forbidden, and women were no longer allowed to study or to work. All of this was well-known to the international community. But the acts that excited the greatest attention to and condemnation of the Taliban from the outside world were acts directed not against the Afghan people directly, but against works of art.

Prior to the arrival of Islam, Buddhism had been the dominant faith in Afghanistan, and many sites and museum collections were rich with artifacts in the Gandharan style that flourished from the first to the seventh century and that fused Buddhist iconography with a Hellenistic and Roman style. In 2001, the Taliban leader Mullah Omar issued a fatwa that called for the destruction of all pre-Islamic statues and sanctuaries in the land. “These statues have been and remain shrines of unbelievers,” he said. “God Almighty is the only real shrine and all fake idols should be destroyed.”9 Within weeks, Taliban forces destroyed thousands of artworks, many of which were in the Kabul Museum. Their most prominent targets, however, were the giant Buddhas of the Bamiyan Valley.

A hundred and fifty miles west of Kabul, the Bamiyan Valley is a broad, fertile basin watered by the Bamiyan River and bordered by rocky cliffs of the Hindu Kush mountains. Here, carved directly into the cliff face, was a 175-foot-tall relief sculpture that was the largest Buddha sculpture in the world. A second sculpture, at 120 feet, was small only in comparison to its colossal neighbor. Other Buddhas, seated and recumbent, were once ranged along the mountainside, and their bodies were covered in brilliant frescoes. Hundreds of artificial caves were dug into the rock to provide cells for meditation and prayer for Buddhist monks. In its heyday the valley housed an enormous monastery and a giant stupa that would have been as eye-catching as the Buddhas.

This extraordinary cluster of Buddhist monuments was mostly built in the sixth and seventh centuries, when Bamiyan was an important node in the ancient Silk Road. As a rare oasis in harsh mountainous terrain it attracted merchants and missionaries and became a prosperous center for religion and trade. From the eighth century Islam began to supplant Buddhism in the region. Buddhist sites fell out of worship, the stupa crumbled, and the vast monastery disappeared, but apart from an attack by a passing conqueror in the twelfth century, when the Buddhas probably lost their faces, the giant sculptures remained relatively intact.

In 2001, as the Taliban tried to destroy the Buddhas, they found it was not an easy task. They first attacked the statues with guns, antiaircraft missiles, and tanks. When these did not suffice, the Taliban brought in explosives experts from Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. On their advice, workers rappelled down the cliff with jackhammers, blasting holes in the sculptures and packing these with dynamite that was detonated in timed explosions. A journalist from the al-Jazeera media network was allowed to film the final stage of the Buddhas’ destruction, and shortly afterward a contingent of twenty international journalists was brought in to observe the now-empty niches.

The Taliban’s determined assault on the Buddhas went forward even as global leaders pleaded with Mullah Omar to spare them. Governments of Islamic countries including Egypt and Qatar tried to reason with the Afghan leaders, and a delegation of clerics led by the mufti of the al-Azhar seminary in Cairo, the most prestigious Sunni center for the study of Islamic law, was flown to the Taliban’s de facto capital of Kandahar to dissuade Mullah Omar from destroying the statues.

Why, then, did the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas become a prestige project for the Afghan leader, a task to be “implemented at all costs”?10 Why, despite the pressure applied by global leaders, did the Taliban invest so much time, labor, and expense in the difficult task of demolition and in ensuring that it was broadcast to the rest of the world? And why was Mullah Omar so determined to destroy the Buddhas two years after he had solemnly promised to protect them? In 1999 he had declared that as there were no Buddhists remaining in Afghanistan, the Buddhas were not idols under worship, and there was no religious reason to attack them. Instead, he said his government considered them “a potential major source of income for Afghanistan from international visitors. The Taliban states that Bamiyan shall not be destroyed but protected.”11 What accounts for the Taliban’s volte-face, in which a religious motivation, earlier dismissed as irrelevant, was used to now justify the attack?

In his essay on the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, Finbarr Barry Flood suggests that the context of the act lies not in medieval religious beliefs but in contemporary world politics.12 The Taliban was recognized as constituting the country’s legitimate government by only three states, and Afghanistan was under economic sanctions. Trying to build links with the international community, it had voluntarily destroyed the country’s opium crop. However, its continuing refusal to surrender Osama bin Laden, who was sheltering in Afghanistan at the time, led to a breakdown in negotiations, and the United Nations imposed fresh sanctions on the country. At this point the Taliban gave up attempts to engage with the international community. Instead it chose a dramatic act to demonstrate its own rejection of the community that had rejected it.

The destruction of the Buddhas even gave the Taliban an opportunity to mock the international community for so greatly valorizing these sculptures. As audiences across the globe expressed horror at their destruction, the Taliban claimed they were horrified at a world that would offer to spend millions of dollars on salvaging artworks while intensifying sanctions that denied essential supplies and threatened Afghan lives. As Flood says, what was under attack here “was not the literal worship of religious idols but their veneration as cultural icons,” not an “Oriental” cult of idol worship but the Western cult of art.13

Flood writes of the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas as “a performance designed for the age of the Internet,” whose “intended audience was . . . neither divine nor local but global.”14 If so, it certainly worked. More than the terrible suffering of ordinary Afghan people, it was the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas that became the symbol of the Taliban’s irredeemable barbarity. Viewers seemed to identify with the Buddhas, projecting their own selves into their crumbling bodies, and much of the reportage spoke of the Buddha figure “gazing” down at the valley or suffering “wounds” on “his” body.

The global circulation of images and information on the destruction of the Buddhas, the global outcry that followed the event, and the global efforts to salvage what might remain of them in the valley distill the events at Bamiyan into a struggle between binary opposites. The ability to see the Buddhas as part of world art and world heritage versus the inability to see them as anything but idols becomes the dividing line between the modern and the medieval, the cultured and the barbaric, the secular and the fanatical. Bamiyan became a cause célèbre, and two years after the ouster of the Taliban in late 2001, the “Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley” were inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List as well as its List of World Heritage in Danger. The new Afghan government welcomed international archaeologists and conservators to Bamiyan, and teams of French, German, Swiss, Austrian, Japanese, and American conservators and archaeologists went to work there, making new discoveries and attempting to preserve and document what remained.

By cooperating with the international community, the new Afghan government distanced itself from the Taliban and its attitude toward cultural heritage. But the dyad of the Taliban-versus-World Heritage actually obscures a third, crucially important yet often overlooked group who were also a prime audience for the Taliban’s destructive actions. For this internal audience that lived in Bamiyan, who were Afghan but not of the Sunni majority, this event had another range of meanings altogether. The Bamiyan Valley is home to the community of Hazaras, a Shia minority that is ethnically, culturally, and religiously distinct from the majority of Afghans. Speaking Hazaragi, a dialect of Persian, and following Shiism, which is considered heretical by orthodox Sunnis, the Hazaras believe themselves to be of Mongol origin, descending from the remnants of the thirteenth-century army of Genghis Khan.

Having displaced the earlier Buddhist inhabitants of the valley, the Hazaras have lived in Bamiyan for centuries and have made the valley and its features their own. The Hazaras may have lost sight of the original meaning of the Buddhas, but they gave them new meanings and incorporated them into their own heritage. In Hazara folklore the taller Buddha statue was identified with a low-born hero called Salsal, and the shorter one was his beloved, a princess called Shahmama. When Shahmama’s father, the ruler of Bamiyan, learned about their love, he set Salsal two challenges: to save the Bamiyan Valley from its frequent flooding and to defeat a dragon that was plaguing the land. Hazaras point to the dam on the nearby Band-e Amir Lake: the dam wall, they say, was built by Salsal. They point also to a nearby rock formation, known as Darya Ajdahar, or Dragon Rock: these are the petrified remains of the dragon that Salsal killed.

A victorious Salsal returned to claim his bride. The bride and groom retreated to two chambers carved into the mountain to be readied for their wedding. But, alas, when the day of the wedding dawned, Salsal was dead: the dragon’s poison had worked its way into his wounds and killed him overnight. His body was frozen stiff into the mountainside. Seeing him dead, Shahmama let out a shriek, then she too died. According to the Hazara legend, the larger of the two Buddhas was the petrified body of the hero Salsal; the smaller, his bride, Shahmama. Both remained on the hillside, frozen in eternal separation. This tragic tale shows how the Hazaras adopted the Bamiyan sculptures and knitted them into other local elements—the Dragon Rock, the dam on the lake—to make them part of the environment. Uncreated by human hands, the two sculptures become part of the natural heritage of the Bamiyan Valley.15

There were other ways in which Hazaras expressed kinship with the statues. Some claimed that their own ancestors had made them; when medieval invaders damaged the statues and destroyed their faces, they believe this was done because the statues’ faces were Hazara faces. This belief reflects the Hazaras’ experience as a persecuted minority in Afghanistan. And through the centuries, the statues have been mascots for the Hazara people, sharing in their suffering and subjugation. Human rights groups believe the Hazaras have been the most oppressed community in Afghanistan since the nineteenth century. When they resisted the control of the ruler of Kabul late that century, an estimated 60 percent of the Hazara population was wiped out on his orders. In subsequent decades they were routinely captured and enslaved. Discrimination continued through the twentieth century but intensified in the Taliban era: when the Hazaras aligned with the Northern Alliance, who were resisting the Taliban, the Taliban in turn declared a jihad against the Hazaras.

Through these vicissitudes, the Hazaras have also tried to tend to the statues. When Hazara fighters wrested control of the Bamiyan area during the Russian occupation of the 1980s, the Hazara warlord Abdul Ali Mazari even assigned soldiers to protect the Buddhas.

However, in January 2001 the Taliban gained control of the Bamiyan Valley, and the Buddhas were destroyed shortly after. Their destruction was aimed at striking fear in the Hazara heart, asserting Taliban dominance, destroying a Hazara cultural symbol, and ruining a potential resource for Bamiyan’s future economy. But the Buddhas were only one aspect of the destruction the Taliban wrought in Bamiyan: the spectacle was the public face of an event intended for the eyes of television viewers. In its shadow was the other face—turned toward internal animosities against Afghanistan’s own minorities. Immediately upon capturing the valley, the Taliban massacred the Hazaras, wiping out entire villages around Bamiyan.

The continuing importance of these now-effaced statues for the Hazaras can be gauged from the frequency with which their names are invoked by the community, at home and in the diaspora. Countless Hazara associations, nongovernmental organizations, and social clubs are named for Shahmama and Salsal. The images of the statues as they once were, as well as the empty niches, are frequently reproduced in Hazara popular culture and social media, becoming a visual symbol of the community and the persecution suffered by it. In 2014, when the Hazara community wished to build a statue to commemorate their leader Abdul Ali Mazari, who was assassinated by the Taliban in 1995, they erected it in front of the ridge where the Buddhas—or rather Salsal and Shahmama—once stood. The homology between the statue commemorating the Hazara hero who was murdered by the Taliban and the empty niches of the destroyed Buddhas is easy to read.

In the months and years since the demolition, Hazara artists, writers, poets, and filmmakers have dwelt on the Buddhas, grieving their loss, critiquing the Taliban, and wishing for a future when the statues return to their niches. Notable among these is Khadim Ali, a Hazara artist who has settled in Pakistan and whose delicate miniature paintings and woven carpets repeatedly delineate the empty niches in Bamiyan. Hafiz Pakzad, a Bamiyan-born French hyperrealist artist, proposed painting an enormous Buddha that would fill the empty niche; a smaller version hung in the rotunda of the Musée Guimet in Paris from 2006 as a remembrance of the erased past.

While international artists have mounted special events in which holograms of the Buddhas are projected onto the cliff, the Hazaras have expressed their desire to actually rebuild the statues. The reaction of heritage experts has been dismissive. “I think trying to rebuild them is the silliest idea I’ve ever heard,” declared Nancy Hatch Dupree, the American historian who dedicated her life to the cultural heritage of Afghanistan and wielded immense power among the organizations that coordinated relief operations there in the post-Taliban era. “You cannot recreate something that was an artistic creation. It was of its time.” Dupree’s concerns seem to have been aesthetic, as she believed it was impossible for the reconstructions to replicate the originals perfectly. “Of course, the people of Bamiyan are anxious to have them rebuilt because they think they’ve lost their tourist attraction,” she conceded in an interview, but “I don’t think so. I think we can build a site museum.”16

Dupree imagined the Hazaras’ desire to rebuild the sculptures came from the economic ambition to create a tourist attraction. But tourism has not ever been a significant part of the Bamiyan economy. Surely it was possible to attribute other motivations to this longing to repair the damage that the Taliban had wrought? To undo this erasure of their heritage, to heal wounds, and to look to a future when the residents of the valley can shape their own future: this could have been the Hazaras’ wish.

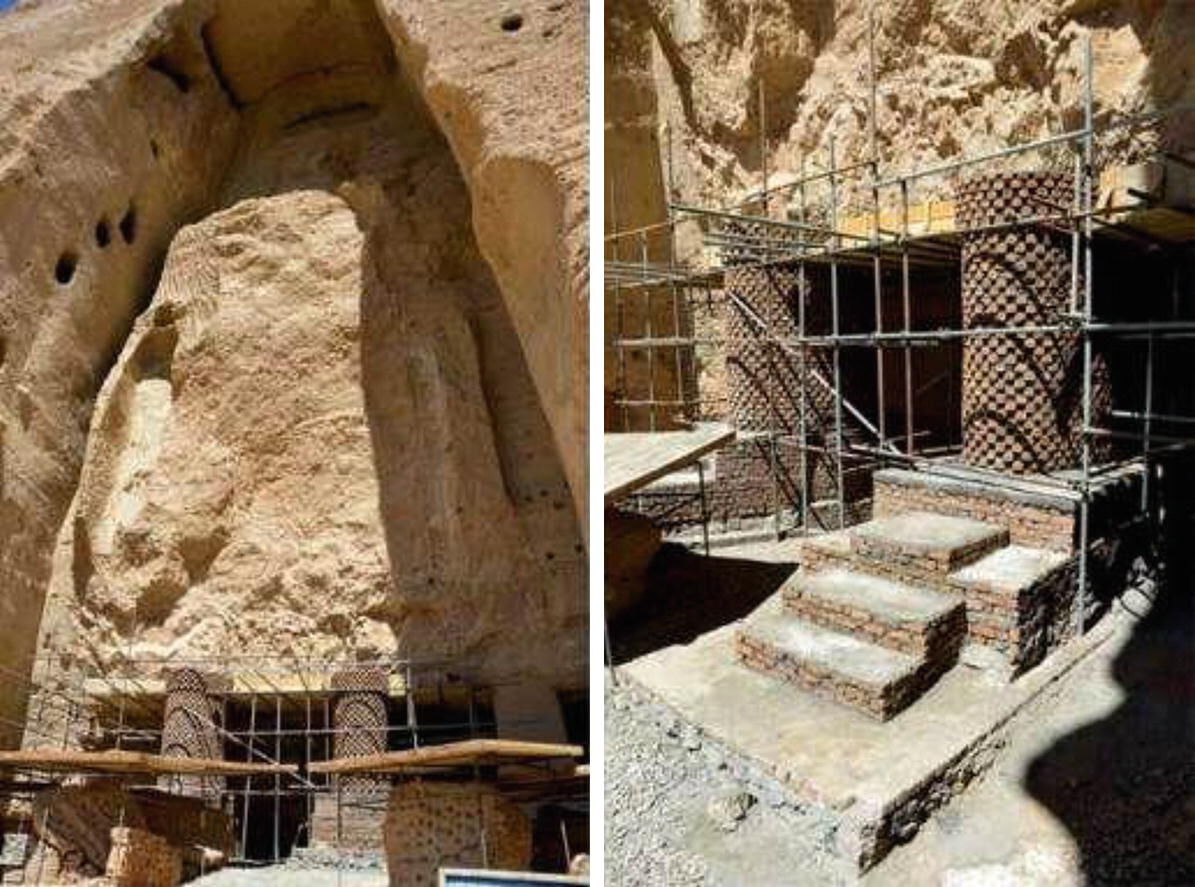

For two decades, the future of the statues, however, remained unclear. At the base of the larger Buddha, archaeologists built a shed to hold all the fragments collected after the Buddhas’ destruction. But so much had been lost that experts believed that, while it might be possible to piece together half of the smaller Buddha, it would be impossible to rebuild the larger one. With so little of the original statues remaining, whatever would be built would be a new construction, resulting in a loss of authenticity for the site. Were this to occur, international experts warned, the reconstruction would contravene the 1964 International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, or the Venice Charter, according to which “[restoration] must stop at the point where conjecture begins.”17 If the Buddhas were reconstructed thus, Bamiyan might risk losing its status as a World Heritage Site. UNESCO favored only the conservation of what remained, which in effect was simply stabilizing the crumbling walls of the empty niches.

Some authorities saw value in maintaining the absence of the Buddhas. While a few scholars and Buddhist leaders felt empty niches best expressed the Buddhist concept of sunyata and nonattachment to material things, others found salutary political lessons in the destroyed sculptures. “The two niches should be left empty, like two pages in Afghan history, so that subsequent generations can see how ignorance once prevailed in our country,” said Zamaryalai Tarzi, the famous Franco-Afghan archaeologist.18 These are views of experts and archaeologists who may be Afghan or sympathetic to Afghans or to Buddhism, but who remain removed from the perspective of the Hazara residents of Bamiyan. In contrast, conservator Michael Petzet, president of the German branch of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), who spent considerable time on-site, seemed more in touch with local sentiments. “I’ve talked with many Afghans,” he said, “and they do not want that their children and grandchildren are forced by the Taliban to see only ruins.”19

In 2014, Petzet and his team began building supporting structures at the base of the smaller Buddha. The brick columns looked suspiciously like feet. As Petzet admitted later, “These feet . . . [were] for the safety of the whole structure, and maybe in the future if the Afghan government wants to make a little bit more, they can build upon this.”20 If it was intended as a nudge in the direction of reconstruction, it did not produce the desired effect. When UNESCO discovered the construction, it petitioned the central government in Kabul, which rushed a team to the site and ordered that further work be halted and the constructed “feet” be taken down (fig. 8.3).

Hazaras reacted against the standards and protocols that UNESCO expected them to follow at Bamiyan. When they were lectured about preserving material authenticity, they pointed out that other World Heritage Sites have involved the entire rebuilding of destroyed sites without any loss of status. The bridge at Mostar and the city center of Warsaw are examples of where the act of faithful rebuilding has been lauded rather than criticized.

If the statues were destroyed by a Taliban that was “exercising upon them the most radical right of the owner,” in the next phase of Afghan history the international community of experts exercises a supraownership by setting up “global” and “professional” standards of custodial care.21 Valuing the physical remains of a historical past, and defining authenticity in material terms, the officials of world heritage organizations were, as Walter Lanchet notes, executing a “new orthodoxy of cultural globalization” that again took Bamiyan’s future out of Hazara hands.22 But their steadfast desire to rebuild the Buddhas and the international interest evoked by the site led to a prolonged debate about the ethics and purpose of reconstruction. Against a Western obsession with conservation philosophy centering on the “original” meanings and authenticity of historical material, a growing number of voices suggested that conservation should also encompass the conserving of skills and knowledge that allow objects and sites to be repaired and renewed. A third strand of argument began to ask whether the question of repairing and reconstructing should not shift focus from recovering things to recovering their meaning. Surely the layers of accreted meaning count for something, where the destroyed statues were not just ancient Buddhas but also mythic lovers and symbols of Hazara suffering.

Despite these debates, Salsal and Shahmama remained absent in Bamiyan. The Taliban had their way, destroying the Buddhas and leaving only empty niches behind. Then the heritage experts had their way, discouraging the rebuilding of the Buddhas, leaving empty niches behind. And now with the return of the Taliban, one can only wonder about the future that lies ahead, not for the Bamiyan Buddhas—for we can guess that—but for the Hazara community that has held them dear for so long.

Conclusion

In the immediate aftermath of a conflict, governments and international organizations first deal with humanitarian issues of critical concern. When they are able to turn their attention to cultural heritage and its reconstruction, it seems a corner has been turned. After all, governments can afford to think of heritage only when more urgent crises are past. The work of post-conflict cultural reconstruction becomes an important sign that the country is on its way to normality and peace.

The truth, unfortunately, is often more complex. In Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, enough time has passed to allow us to see the shape cultural reconstruction can take. When a conflict ends with clear winners and losers, the processes of reconstruction offer yet another opportunity for the powerful to reward their supporters and dispossess their opponents. Projects of archaeological exploration or monument conservation become instruments by which social hierarchies are reified, majorities are empowered, and minorities become further marginalized. Such processes of “authoritarian reconstruction” only serve to emphasize the fault lines existing in society.23 Often these are the very fault lines that had generated the conflict in the first place. By emphasizing them, the very processes of post-conflict reconstruction that are seen as offering healing may arouse resentment, foreshadowing the eventual return of conflict. Only a reading close to the ground can make us aware of the inequities that can masquerade as cultural reconstruction and demand accountability in its place.

Biography

- Kavita SinghKavita Singh is professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics of Jawaharlal Nehru University, where she teaches courses in the history of Indian painting, particularly the Mughal and Rajput schools, and the history and politics of museums. Singh has published on secularism and religiosity, fraught national identities, and the memorialization of difficult histories as they relate to museums in South Asia and beyond. She has also published essays and monographs on aspects of Mughal and Rajput painting, particularly on style as a signifying system. In 2018 she was awarded the Infosys Prize for Humanities and in 2020 was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Suggested Readings

- Sri Lanka

- Malathi de Alwis, “Trauma, Memory, Forgetting,” in Sri Lanka: The Struggle for Peace in the Aftermath of War, ed. Amarnath Amarasingham and Daniel Bass (London: Christopher Hurst, 2016), 147–61.

- Jude Fernando, “Heritage & Nationalism: A Bane of Sri Lanka,” Colombo Telegraph, 30 March 2015, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/heritage-nationalism-a-bane-of-sri-lanka/.

- Sasanka Perera, Violence and the Burden of Memory: Remembrance and Erasure in Sinhala Consciousness (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan, 2016).

- Samanth Subramanian, This Divided Island: Stories from the Sri Lankan War (London: Penguin Books, 2014).

- Nira Wickramasinghe, “Producing the Present: History as Heritage in Post-war Patriotic Sri Lanka,” Economic and Political Weekly 48, no. 43 (2013): 91–100.

- Afghanistan

- Finbarr Barry Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” Art Bulletin 84, no. 4 (2002): 641–59.

- Ankita Haldar, “Echoes from the Empty Niche: Bamiyan Buddha Speaks Back,” Himalayan and Central Asian Studies 16, no. 2 (2012): 53–91.

- Luke Harding, “How the Buddha Got His Wounds,” Guardian, 3 March 2001, https://www.guardian.co.uk/Archive/Article/0,4273,4145138,00.html.

- Syed Reza Husseini, “Destruction of Bamiyan Buddhas: Taliban Iconoclasm and Hazara Response,” Himalayan and Central Asian Studies 16, no. 2 (2012): 15–50.

- Llewellyn Morgan, The Buddhas of Bamiyan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Notes

There have been several other important Tamil political and militant groups as well, such as the far-left Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). ↩︎

Amir Ali, “Erasing the Cultural Leftover of Tamils to Convert Sri Lanka into Sinhala Country,” The Weekend Leader 2, no. 31, 4 August 2011, https://www.theweekendleader.com/Causes/615/exclusive-inside-lanka.html. ↩︎

Renowned Sri Lankan–Tamil historian and archaeologist Sivasubramaniam Pathmanathan has gone on record to complain that archaeological projects that could show an ancient Tamil presence in Sri Lanka have not been given approval by the archaeological authorities, while those that would show an early Sinhalese Buddhist presence in Tamil homelands have gained funding. See Nira Wickramasinghe, “Producing the Present: History as Heritage in Post-war Patriotic Sri Lanka,” Economic and Political Weekly 48, no. 43 (2013): 91–100. ↩︎

See Wickramasinghe, “Producing the Present”; and Jude Fernando, “Heritage & Nationalism: A Bane of Sri Lanka,” Colombo Telegraph, 30 March 2015, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/heritage-nationalism-a-bane-of-sri-lanka/. ↩︎

Samanth Subramanian, This Divided Island: Stories from the Sri Lankan War (London: Penguin Books, 2014), 196–99. ↩︎

TamilNet, “Archaeologists Enter Omanthai Statue Dispute,” 7 June 2005, https://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=15100. ↩︎

Fernando, “Heritage & Nationalism.” ↩︎

This essay was written prior to the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. Needless to say, the reinstallation of the Taliban does not augur well for the future of Afghanistan’s Buddhist material heritage or for the cultural and human rights of its minorities, including the Shia Hazaras who are the focus of this section of the essay. ↩︎

Quoted in Finbarr Barry Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” Art Bulletin 84, no. 4 (2002): 655. ↩︎

After Mullah Omar decreed that the Taliban would destroy all statues in areas under their control, the Taliban ambassador to Pakistan issued a statement declaring, “The fatwa . . . [will] be implemented at all costs.” The ambassador clearly understood that this act would adversely affect the Taliban government and would prolong the sanctions against Afghanistan; the act would be carried out in the face of this knowledge. See Jamal J. Elias, “(Un)making Idolatry: From Mecca to Bamiyan,” Future Anterior 4, no. 2 (2007): 17, citing Ambassador Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef. ↩︎

Luke Harding, “How the Buddha Got His Wounds,” Guardian, 3 March 2001, http://www.guardian.co.uk/Archive/Article/0,4273,4145138,00.html. ↩︎

Flood, “Between Cult and Culture.” ↩︎

Flood, “Between Cult and Culture,” 651. ↩︎

Flood, “Between Cult and Culture,” 651. ↩︎

I am grateful to Syed Reza Husseini, who brought the Hazaras to my attention and shared much information about them. For his essay on the subject, see Syed Reza Husseini, “Destruction of Bamiyan Buddhas: Taliban Iconoclasm and Hazara Response,” Himalayan and Central Asian Studies 16, no. 2 (2012): 15–50. ↩︎

Asia Society, “Preserving Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage: An Interview with Nancy Hatch Dupree [2002],” https://asiasociety.org/preserving-afghanistans-cultural-heritage-interview-nancy-hatch-dupree. ↩︎

International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter 1964), Art. 9. ↩︎

Quoted in Frédéric Bobin, “Disputes Damage Hopes of Rebuilding Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Buddhas,” Guardian, 10 January 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/10/rebuild-bamiyan-buddhas-taliban-afghanistan. ↩︎

Quoted in Rod Nordland, “Countries Divided on Future of Ancient Buddhas,” New York Times, 22 March 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/23/world/asia/countries-divided-on-future-of-ancient-buddhas.html. ↩︎

Nordland, “Countries Divided on Future of Ancient Buddhas.” ↩︎

Dario Gamboni, “World Heritage: Shield or Target?,” Conservation (Newsletter of the Getty Conservation Institute) 16, no. 2 (2001): 5–11, http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/16_2/feature.html. ↩︎

Walter Lanchet, “World Heritage in Practice: The Examples of Tunis (Tunisia) and Fez (Morocco),” in Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Working Paper Series, vol. 128, International Association for the Study of Traditional Environments, 2000, 39–47. ↩︎

Steven Heydemann, “Reconstructing Authoritarianism: The Politics and Political Economy of Post-conflict Reconstruction in Syria,” in The Politics of Post-conflict Reconstruction, ed. Marc Lynch (Washington, DC: George Washington University, September 2018), Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) Studies no. 30, 14. ↩︎