التراث المدوَّن للعالم الإسلامي

سابين شميدكي

تراث المخطوطات الإسلامية عرضة للخطر بأشكال عديدة، ولاسيما التعامل غير المناسب معها والسرقة والظروف المناخية السيئة والتدمير المتعمّد. وقد تكررت في العقود الأخيرة حالات للتدمير المتعمد للمخطوطات الإسلامية، ويستمر بيع المخطوطات الإسلامية ذات الأصل المبهم إلى مجموعات خاصة. ودمار التراث الثقافي للعالم الإسلامي يمثل فاجعة لا يمكن تخيّل أبعادها، بحيث أن الكتب ومكتبات المخطوطات هي من بين التجليات الثقافية والمؤسسات الأكثر تضررًا.

ملخص

يُشكل التراث المدوَّن للعالم الإسلامي إرثًا أكبر مما يمكن تخيّله، وجانب كبير من الثقافة المدوَّنة للعالم الإسلامي لا تزال إلى يومنا هذا محفوظة ضمن مخطوطات. ولا يزال تراث المخطوطات الإسلامية عرضة للخطر بأشكال عديدة، ولاسيما التعامل غير المناسب معها والتعرّض للضوء والسرقة والظروف المناخية السيئة والتدمير المتعمّد. وقد تكررت في العقود الأخيرة حالات للتدمير المتعمد للمخطوطات الإسلامية. وشمل ذلك تفجير مكتبات ومتاحف في كوسوفو والبوسنة على يد القوميين الصرب عام 1992، ونهب وتدمير مكتبات مهمة للمخطوطات في العراق عقب حرب الخليج عام 1991، ومجددًا عند الغزو والاحتلال منذ عام 2003. تُشكِّل الطائفية مصدرًا آخرًا يهدد جوانب من التراث الثقافي الإسلامي: حيث يتم استهداف مكتبات تضمّ مخطوطات يُنظر إليها على أنها تضمّ وجهات نظر مختلفة، وينطبق الأمر نفسه على المعالم التاريخية التي دمرها متطرفون مسلمون في العقود الماضية كمحاولة منهم “لتطهير” الإسلام.

穆斯林世界的文字遗产

莎宾娜·施密特克 (Sabine Schmidtke)

伊斯兰教的手稿遗产受到多种形式的威胁——操作不当、偷窃、恶劣的天气状况以及肆意破坏。在过去数十年间,蓄意破坏伊斯兰教手抄本的案例屡见不鲜,而来源不明的伊斯兰教手抄本持续被拍卖,落入私人手中。穆斯林世界文化遗产遭到的灾难性破坏无可估量,其中受到最大冲击的文化形式和机构堪属书籍与手稿图书馆。

摘要

穆斯林世界的文字遗产是文化遗产中至关重要的组成部分,其中伊斯兰教的多数文字遗产至今仍以手稿的形式保存。这种手稿遗产持续遭到多种形式的威胁——操作不当、暴露、偷窃、恶劣的天气状况以及肆意破坏。在过去数十年间,蓄意破坏伊斯兰教手稿的案例屡见不鲜。例如,1992 年科索沃及波斯尼亚的多座图书馆与博物馆遭到塞尔维亚民族主义者的轰炸,以及在 1991 年海湾战争的余波中以及自 2003 年以来伊拉克不断被他国侵略和占领,多数手稿图书馆遭到洗劫和破坏。宗派主义对伊斯兰教的部分文化遗产构成另一种威胁:图书馆若是藏有被视为持有异端观点的手稿,即成为被摧毁的目标,而历史纪念碑亦是如此,它们在过去数十年间不断被穆斯林极端分子以“净化”伊斯兰教为名摧毁。

Islamic manuscript heritage is threatened in many ways—improper handling, theft, inclement climatic conditions, and willful destruction. Over the past several decades there have been repeated cases of deliberate destruction of Islamic manuscripts, and Islamic manuscripts of uncertain provenance continue to be auctioned off into private hands. The destruction of the cultural heritage of the Muslim world is a calamity beyond reckoning, with books and manuscript libraries among the hardest hit cultural forms and institutions.

Abstract

The written heritage of the Muslim world constitutes a vast cultural heritage beyond reckoning, with much of the written culture of the Islamic world still today preserved in manuscript form. This manuscript heritage continues to be threatened in many ways—improper handling, exposure, theft, inclement climatic conditions, and willful destruction. Over the past several decades there have been repeated cases of deliberate destruction of Islamic manuscripts. These include the bombing of libraries and museums in Kosovo and Bosnia by Serbian nationalists in 1992 and the looting and destruction of major manuscript libraries in Iraq in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War and again with the US invasion and occupation from 2003. Sectarianism poses another threat to aspects of Islamic cultural heritage: libraries holding manuscripts that are seen as containing deviant views are targeted for destruction, and the same holds for historical monuments, which have been destroyed over the past few decades by Muslim extremists in an attempt to “purify” Islam.

Le patrimoine écrit du monde musulman

Sabine Schmidtke

Le patrimoine des manuscrits islamiques est menacé de bien des manières, notamment par des manipulations inappropriées, des vols, des conditions climatiques défavorables, et leur destruction intentionnelle. Au cours des décennies passées, des cas répétés de destruction délibérée de manuscrits islamiques se sont produits, et certains de ces ouvrages d’une origine incertaine continuent d’être vendus aux enchères à des parties privées. La destruction du patrimoine culturel du monde musulman est une catastrophe d’une portée inestimable, les livres et les bibliothèques de manuscrits étant parmi les formes et institutions culturelles les plus durement frappées.

Résumé

Le patrimoine écrit du monde musulman constitue un patrimoine culturel d’une valeur inestimable, la plus grande partie de la culture écrite du monde islamique étant encore de nos jours préservée sous une forme manuscrite. Ce patrimoine des manuscrits islamiques continue d’être menacé de bien des manières, notamment des manipulations inappropriées, des vols, des conditions climatiques défavorables, et leur destruction intentionnelle. Au cours des décennies passées, des cas répétés de destruction délibérée de manuscrits islamiques se sont produits. On peut citer le bombardement des bibliothèques et des musées au Kosovo et en Bosnie par les nationalistes serbes en 1992, ainsi que le pillage et la destruction de bibliothèques de manuscrits de premier plan en Irak à la suite de la Guerre du Golfe en 1991, puis de nouveau avec l’invasion et l’occupation à compter de 2003. Le sectarisme constitue une autre menace pour certains aspects du patrimoine culturel islamique : les bibliothèques détenant des manuscrits jugés comme contenant des opinions dissidentes sont menacés de destruction. Il en est de même pour les monuments historiques ayant été détruits au cours des précédentes décennies par des musulmans extrémistes lors de tentatives de « purification » de l’islam.

Письменное наследие исламского мира

Сабин Шмидтке

Ценные исламские рукописи подвергаются таким опасностям как неосторожное обращение, кражи, неблагоприятные климатические условия и намеренное уничтожение. За несколько последних десятилетий неоднократно имели место случаи намеренного уничтожения исламских рукописей, в то время как исламские рукописи неустановленного происхождения уходят с аукционов в частные владения. Уничтожение культурного наследия исламского мира происходит в катастрофических масштабах. И в первую очередь страдают такие культурные формы и институты как книжные собрания и библиотеки рукописей.

Краткое содержание

Исламские письменные памятники являются бесценным культурным наследием. Бóльшая часть письменной исламской культуры до настоящего времени представлена в виде рукописей. Это рукописное наследие подвергается таким опасностям как неправильное обращение, нарушение условий хранения, кражи, неблагоприятные климатические условия и намеренное уничтожение. За несколько последних десятилетий неоднократно имели место случаи намеренного уничтожения исламских рукописей. Среди таковых бомбардировки библиотек и музеев в Косово и Боснии сербскими националистами в 1992 году, разграбление и уничтожение крупных библиотек рукописей в Ираке как результат войны в Персидском заливе в 1991 году, а затем во время вторжения и оккупации с 2003 года. Кроме того, опасность для исламского культурного наследия представляет собой межконфессиональная вражда. Библиотеки, в которых хранятся «неблагонадежные» рукописи, становятся мишенью агрессии. То же происходит и с историческими памятниками, которые гибнут от рук исламских экстремистов, в течение последних нескольких десятилетий пытающихся «очистить» ислам.

El patrimonio escrito del mundo musulmán

Sabine Schmidtke

El patrimonio manuscrito islámico se ve amenazado de muchas formas: una manipulación inadecuada, robos, condiciones climáticas inclementes y destrucción deliberada. Durante las últimas décadas, se han dado repetidos casos de destrucción deliberada de manuscritos islámicos y se continúan subastando manuscritos islámicos de procedencia incierta que terminan en manos de particulares. La destrucción del patrimonio cultural del mundo islámico es una calamidad incalculable, en la que libros y bibliotecas de manuscritos han sido unas de las formas e instituciones culturales más afectadas.

Resumen

El patrimonio escrito del mundo musulmán constituye un patrimonio cultural inestimable, ya que gran parte de la cultura escrita del mundo islámico continúa preservándose en forma de manuscritos. Este patrimonio manuscrito continúa viéndose amenazado de muchas formas: una manipulación inadecuada, exposición, robos, condiciones climáticas inclementes y destrucción deliberada. Durante las últimas décadas, se han dado repetidos casos de destrucción deliberada de manuscritos islámicos. Ello incluye el bombardeo de bibliotecas y museos en Kosovo y Bosnia por parte de nacionalistas serbios en 1992 y el saqueo y destrucción de importantes bibliotecas de manuscritos en Irak tras la guerra del Golfo de 1991 y nuevamente con la invasión y ocupación de 2003. El sectarismo supone otra amenaza a distintos aspectos del patrimonio cultural islámico: las bibliotecas que contienen manuscritos con perspectivas que se consideran desviadas son blanco de la destrucción, y lo mismo ocurre con los monumentos históricos, que han sido destruidos a lo largo de las últimas décadas por extremistas musulmanes en un intento de “purificar” el islam.

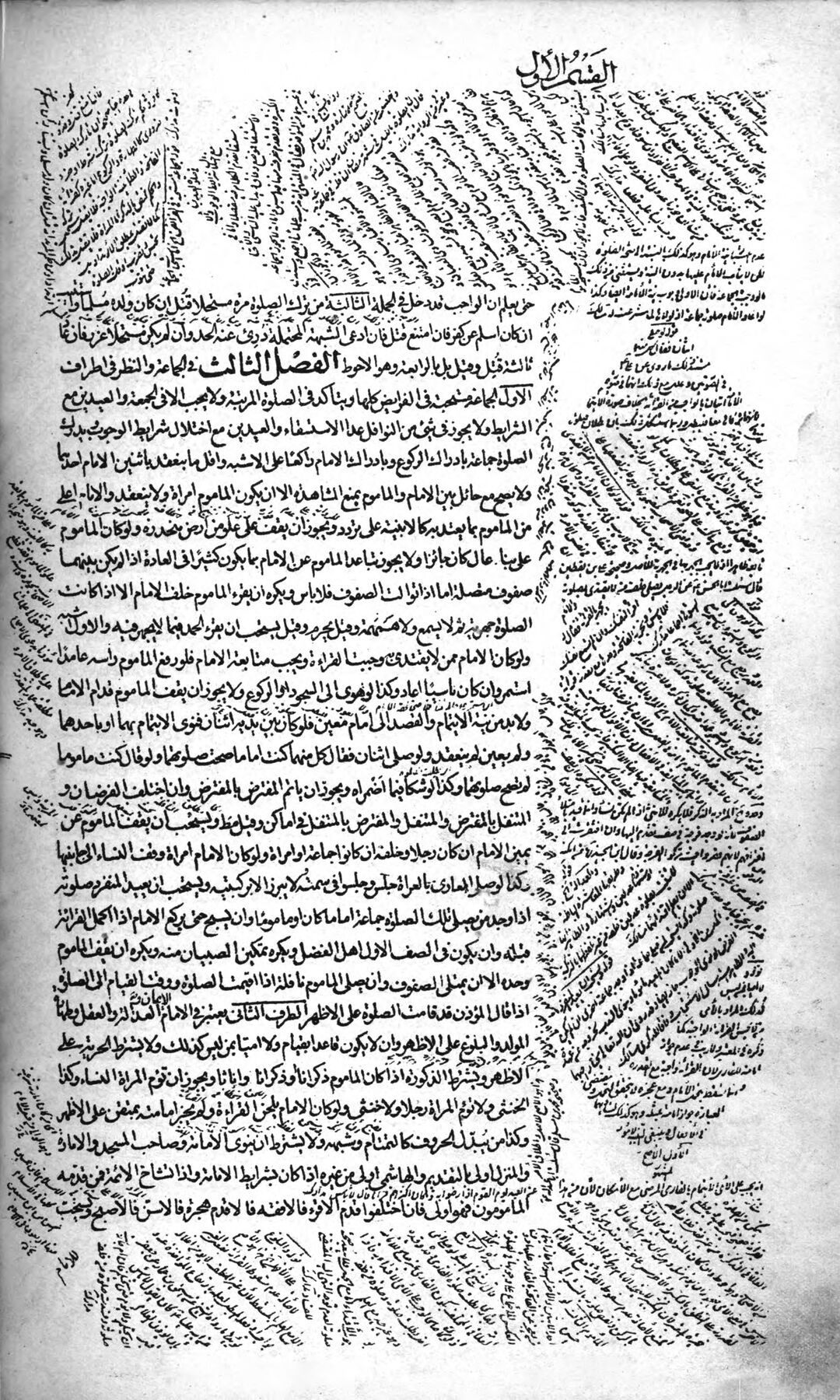

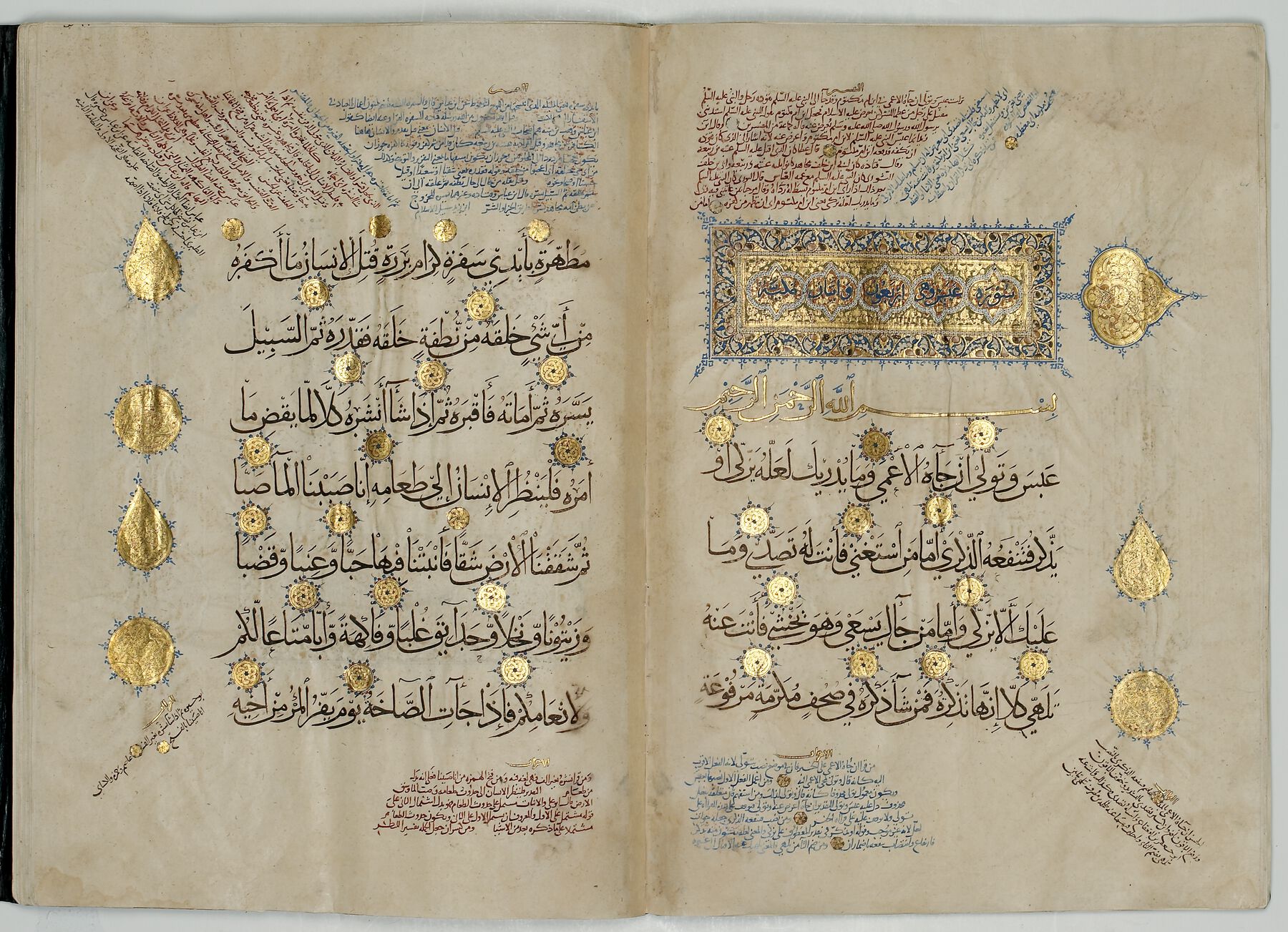

Over the past several decades, digital collections of texts produced by Muslim authors writing in Arabic during the premodern period have mushroomed. Major libraries include al-Maktaba al-Shāmila, currently containing some seven thousand books;1 Noor Digital Library, with 35,169 books to date;2 PDF Books Library, currently containing 4,355 books;3 Arabic Collections Online (ACO), providing access to 15,131 volumes;4 Shia Online Library, with 4,715 books;5 and al-Maktaba al-Waqfiyya, containing some ten million pages of published books (in addition to a growing number of manuscript surrogates),6 to name only the most important. Moreover, since printing technologies were adopted in the Islamic world at a relatively late stage and slow rate (fig. 5.1), much of the written cultural production of the Islamic world is still preserved in manuscript form. And although there has been a steady rise in the publication of manuscript catalogues all over the Islamic world over the past hundred years, much material is still unaccounted for, and discoveries of titles that were believed to have been lost or that were entirely unknown regularly occur. In parallel, numerous libraries have started to digitize their collections of Islamic manuscripts, with a fair number providing open access to their holdings through institutional digital repositories, in addition to a growing number of online gateways to such manuscripts.7 At the same time, what is available online, whether published or in manuscript form, is only the tip of the iceberg.

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1We do not possess reliable data that would allow us to quantify the overall literary production by Muslim scholars over the past 1,500 years, nor do we have estimates of the total number of preserved manuscripts. However, the following figures, randomly chosen, may provide some idea of the overall scope of the corpus. The Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul, one of the most important libraries in Turkey, though just one among many, holds some one hundred thousand manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Turkish, and the estimated number of Islamic manuscripts in all Turkish libraries is three hundred thousand (fig. 5.2).8 The Union Catalogue of Manuscripts in Iranian Libraries, published in 2011 in thirty-five volumes, lists some four hundred thousand manuscripts in Arabic and Persian, not including the holdings of the many uncatalogued private collections in the country. Estimates of the total number of manuscripts in the countless public and private libraries in Yemen, most of which are only partly catalogued, if at all, range from forty thousand to one hundred thousand codices. Moreover, libraries with significant holdings of Islamic manuscripts are not confined to regions that are (or were) part of the Islamic world—they are spread all over the world. Important and substantial collections of Islamic manuscripts can be found across Europe, Russia, North America, and Australia as well as East Asia (fig. 5.3).

Figure 5.3

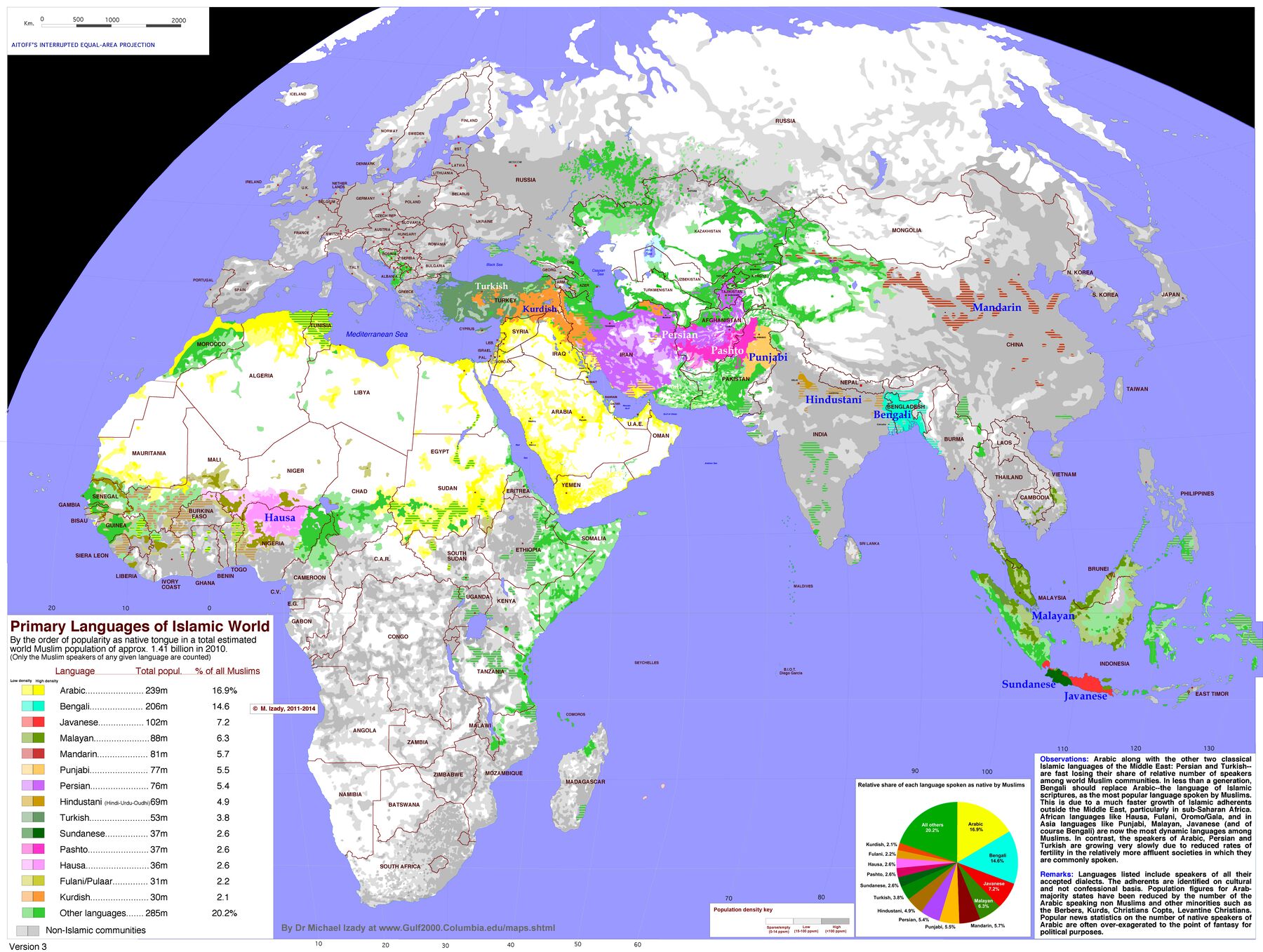

Figure 5.3Further, while Jan Just Witkam rightly remarks that “Arabic traditional literature is probably the largest body of literature in the world,”9 it should be kept in mind that Arabic is only one of many Islamic languages. The geographical expansion of the Islamic world to reach from West Africa and Islamic Spain to Central and South and East Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indonesian archipelago, and the Volga region and other parts of Eastern Europe, as well as the linguistic variety that this spread implies, gave rise to a highly variegated literary production of enormous dimensions. And although one might distinguish geographically between core and periphery (the historical heartlands of Islam versus regions that became part of the Islamic world in later periods) and of philology (Arabic as the language of the Qurʾan and of the Prophet Muhammad versus any other Islamic languages), the resulting conventional hierarchy is unjustified and illusory, as is any attempt to define orthodoxy versus heresy (fig. 5.4). Moreover, starting in the second half of the twentieth century there has been a Muslim diaspora in Western Europe, the United States, and Australia, stimulating its own cultural production in languages that until recently had not been considered Islamic languages.

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4Modern Attempts to Account for the Arabic/Islamic Written Heritage

By the beginning of the twentieth century, several bibliographical enterprises were underway that attempted to provide overviews of the literary production of the Muslim world, or at least parts of it. One of these was the renowned Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur (GAL) compiled by the German orientalist Carl Brockelmann (1868–1956). Volume 1 was published in 1898, covering the classical period up to 1258, and volume 2 in 1902, covering the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries. To render his enterprise feasible, from the outset Brockelmann restricted the project’s scope: while his conceptualization of “literature” was broad, encompassing “all verbal utterances of the human mind,”10 he considered only Arabic titles, excluding writings by Muslims in any other language, and he limited himself to listing surviving works, ignoring titles that were known only from quotations and references. He also excluded titles by non-Muslim authors. Brockelmann’s GAL prompted others to compile counterparts to fill in some of these gaps: Moritz Steinschneider (1816–1907) surveyed Arabic literature by Jewish authors in Die arabische Literatur der Juden (1902), and the British scholar Charles Ambrose Storey (1888–1968) devoted most of his academic career to Persian Literature: A Bio-bibliographical Survey (1927–90).11 Georg Graf (1875–1955) covered Christian Arabic literature in the five-volume Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur (GCAL, 1944–53).

The GAL was based on the few available sources at the time—namely Kashf al-ẓunūn, a bibliographical encyclopedia by the seventeenth-century Ottoman polymath Hajji Khalifa (or Katib Çelebi, d. 1656), listing some fifteen thousand book titles, mostly in Arabic, as well as some thirty-five published manuscript catalogues of collections in Europe, Istanbul, Cairo, and Algiers.12 Brockelmann estimated in the preface to volume 1 of the GAL that “it would take at least a further century of hard philological work before even the most important landmarks of Arabic literature would be known and accessible”13—a serious underestimation, in fact, of what lay ahead.

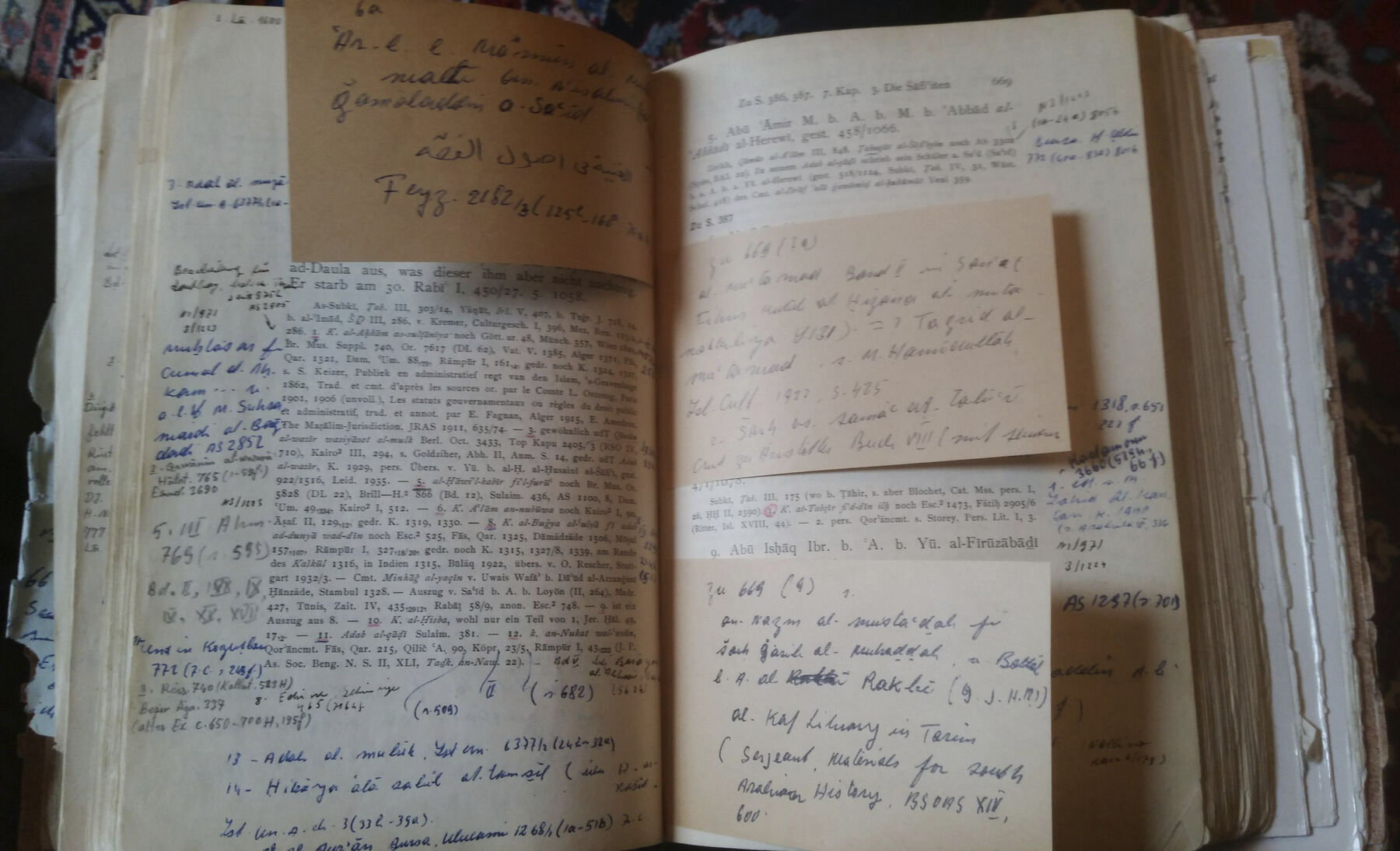

The GAL turned out to be unsatisfactory from the beginning. Between 1937 and 1942, Brockelmann published three supplementary volumes, followed in 1943 and 1949 by an updated version of the original two volumes, containing about twenty-five thousand titles by some eighteen thousand authors. To illustrate the quantitative discrepancy between the corpus of extant Arabic Islamic literature described by Brockelmann and what has become accessible since, it suffices to juxtapose his list of thirty-five manuscript catalogues consulted for the first edition and the expanded list of 136 consulted for the updated edition14 with the World Survey of Islamic Manuscripts (1992–94), published in four volumes with close to 2,500 pages in total, constituting a “comprehensive bibliographical guide to collections of Islamic manuscripts in all Islamic languages in over ninety countries throughout the world.”15 Today, close to three decades after its publication, the World Survey of Islamic Manuscripts is seriously outdated, and a revised enlarged edition would easily fill six or more volumes.16 Although Brockelmann’s GAL is still regularly consulted by scholars as a first point of departure (in fact, an English translation was published as late as 2017),17 it is widely agreed that any attempt to publish a revised and enlarged version is unrealistic.18 Today, scholars engaged in surveying the written production of Muslims restrict themselves to specific subjects, areas, and time periods. The Turkish-German scholar Fuat Sezgin (1924–2018), for example, who published a biobibliographical survey of Arabic literature, Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums (GAS, 1967–2015), in seventeen volumes, limited his focus to the early Islamic centuries, up to the mid-eleventh century (fig. 5.5).

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.5Other examples in Western scholarship include Ulrich Rebstock’s three-volume survey of Arabic literature by Mauritanian authors, Maurische Literaturgeschichte (2001), describing some ten thousand titles by about five thousand authors from the sixth through eighteenth centuries;19 and international projects such as “Islam in the Horn of Africa: A Comparative Literary Approach” (IslHornAfr), funded by the European Research Council.20 There are also born-digital initiatives such as “Historia de los Autores y Transmisores Andalusíes” (HATA), providing information on “works written and transmitted in al-Andalus from the eighth to the fifteenth century with a total of 5,007 Andalusi authors and transmitters, 1,391 non Andalusi authors and transmitters and 13,730 titles written and transmitted in al-Andalus,”21 and HUNAYNNET, an “attempt at compiling a digital trilingual and linguistically annotated parallel corpus of Greek classical scientific and philosophical literature and the Syriac and Arabic translations thereof,” also funded by the European Research Council.22 Digital platforms and tools are being developed in a number of current projects, with the aim of continuing Brockelmann’s earlier bibliographical endeavors and developing innovative ways to survey and study Arabic written heritage. Among the most important such projects are Bibliotheca Arabica, funded by the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Leipzig (which began in 2018 and is proposed to continue until 2035),23 and “KITAB: Knowledge, Information Technology, and the Arabic Book,” funded by the European Research Council and the Aga Khan University, London.24

Middle Eastern scholars also began to embark on large-scale bibliographical enterprises around the beginning of the twentieth century. Like Brockelmann, who took Hajji Khalifa’s Kashf al-ẓunūn as his point of departure, the Ottoman Iraqi scholar Ismaʿil Basha al-Baghdadi (d. 1919) expanded on Hajji Khalifa’s work in his Īḍāḥ al-maknūn fī dhayl ʿalā Kashf al-ẓunūn, with entries for more than forty thousand titles by some nine thousand authors ranging from the seventh to the early twentieth century.25 But this is, again, only the tip of the iceberg—Ismaʿil Basha al-Baghdadi not only focused on Arabic material but also disregarded works composed by non-Sunni scholars and by authors who flourished beyond the main centers of learning.

Challenged by the statements of Christian Lebanese Jurji Zaydan (1861–1914) in his Tārikh ādāb al-lugha al-ʿarabiyya (1910–13, published in four volumes) belittling the contributions of Twelver Shiʿites to Arabic literature, a number of Shiʿite scholars strove to counter this claim by collecting, transcribing, and publishing as many earlier Shiʿite texts as possible. Their endeavors resulted in two biobibliographical encyclopedias—namely, the four-volume Kashf al-astār ʿan wajh al-kutub wa-l-asfār by al-Sayyid Ahmad al-Husayni al-Safaʾi al-Khwansari (1863/64–1940/41), and, more importantly, Agha Buzurg al-Tihrani’s (1876–1970) monumental al-Dharīʿa ilā taṣānīf al-Shīʿa, a comprehensive bibliographical encyclopedia of Twelver Shiʿite literature, consisting of twenty-eight volumes and describing a total of 53,510 books. Agha Buzurg not only consulted available manuscript catalogues and publications but also traveled widely to visit the relevant public and private libraries in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and the Hijaz (a western region of Saudi Arabia), in all of which he had unprecedented access to a large number of manuscripts. The result is an unsurpassed work of meticulous scholarship, and the Dharīʿa still constitutes the most important reference work for scholars engaged in the study of Twelver Shiʿism.

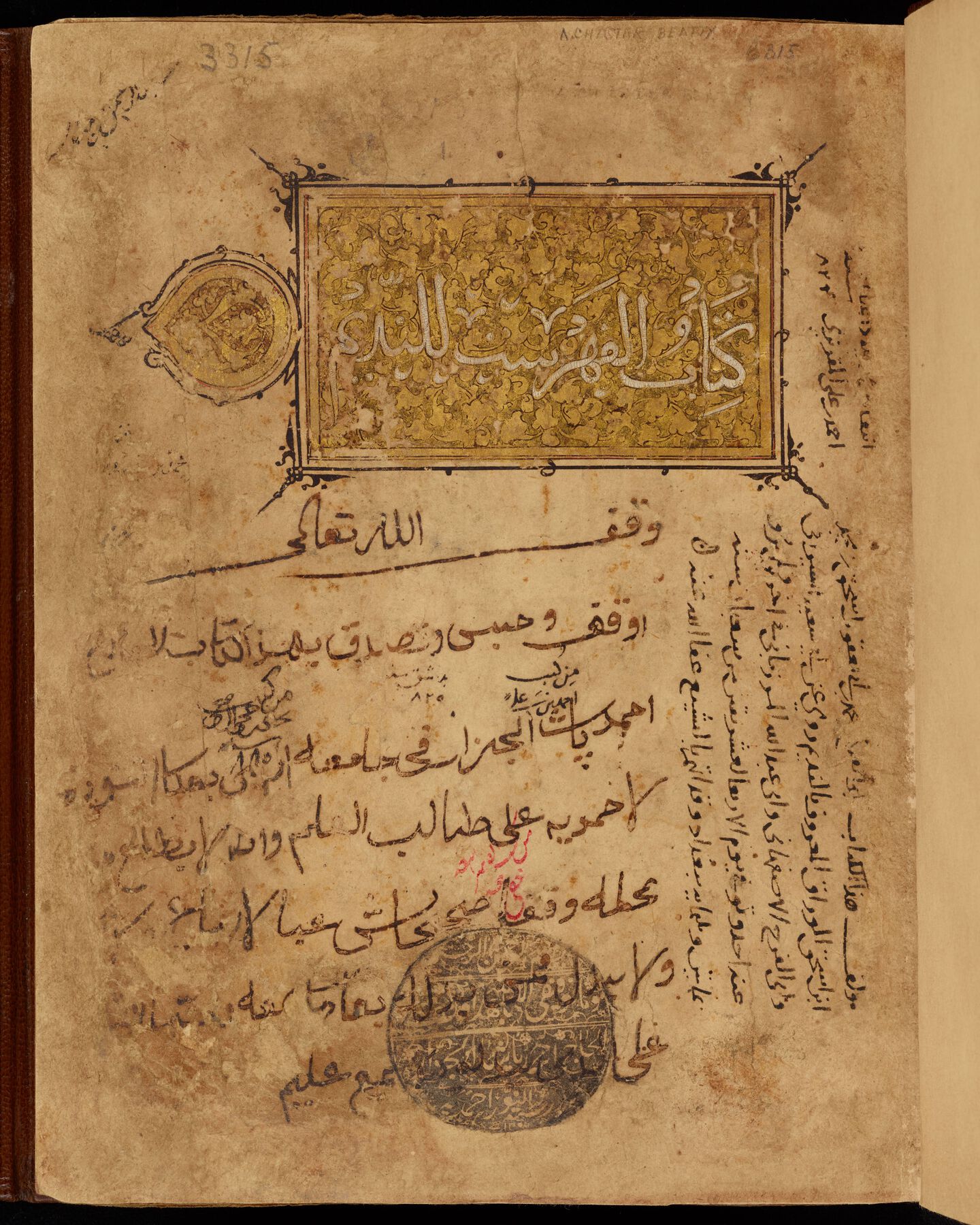

Book Inventories in the Premodern Islamic World

Whereas the biobibliographical works of Muslim scholars such as Ismaʿil Basha al-Baghdadi or Agha Buzurg al-Tihrani are de facto modern publications, they continue a centuries-long tradition that can be traced back to the early Islamic era. In 988, some three hundred years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, the Baghdad bookseller Ibn al-Nadim (d. 990) compiled a comprehensive Catalog of the entire Arabic textual corpus that he had been able to get his hands on, and his bibliographical work in its current, incomplete state lists the works of some 3,500 or 3,700 authors—an impressive monument to the book revolution that had been brought about by the nascent Islamic civilization by the early ninth century (fig. 5.6).26 Many of the titles Ibn al-Nadim includes have not come down to us, and the information he provides in the Catalog is thus of primary significance. Comparable enterprises from later centuries include Miftāḥ al-saʿāda wa-miṣbāḥ al-siyāda, a comprehensive inventory of books arranged according to disciplines of learning by Ottoman scholar Ahmad b. Mustafa Taşköprüzade (d. 1560), and Fahrasat al-kutub wa-l-rasāʾil, an overview of Ismaʿili literature by Daʾudi Bohra scholar Ismaʿil b. ʿAbd al-Rasul al-Majduʿ (d. 1769/70).

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6Moreover, the historical sources refer to large-scale libraries in the intellectual hubs of the Muslim world from early on. The Fatimid royal libraries, for example, are said to have amassed some 1.5 million volumes toward the end of the dynasty in the early twelfth century. Whether or not the figure is exaggerated, there is no doubt that their holdings were enormous and comprised the full range of what existed at the time in Arabic.27 One of the most important libraries during the Abbasid period was founded in Karkh (Baghdad), attached to the academy of learning (dar al-ʿilm), by the Shiʿi Shapur b. Ardashir (d. 1035/36), the erstwhile vizier of the Buyid ruler Bahaʾ al-Dawla. The library existed for six decades, and its holdings amounted to some ten thousand volumes, until it was destroyed in 1059, during the Seljuq Tughril Beg’s march on Baghdad (fig. 5.7).

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7Although we know very little about the history, holdings, and organization of most early rulers’ libraries, as the narrative sources provide primarily anecdotal evidence, an increasing number of documentary sources have come to light over the past several decades—inventories of property and records of sold objects, endowment deeds, inheritance inventories, confiscation registers, gift registers, court records, account books, and library catalogues, as well as paratextual material in manuscript codices—informing us about the history, organization and management, arrangement, and holdings of a growing number of libraries from the tenth century onward, and more discoveries can be expected within this vibrant field of scholarship. Fairly detailed descriptions are available, for example, of the private library of Baghdad scholar Abu Bakr al-Suli (d. 947).28

Among the earliest extant library catalogues are a register of the holdings of the library of the Great Mosque of Qayrawan in Tunisia (dated 1294)29 and a catalogue of the library of the mausoleum of al-Malik al-Ashraf (r. 1229–37) in Damascus, which lists some two thousand books.30 The thirteenth-century Twelver Shiʿite scholar Radi al-Din Ibn Tawus compiled a since-lost catalogue of the holdings of his personal library, al-Ibāna fī maʿrifat (asmāʾ) kutub al-khizāna, to which he later added as a supplement his Saʿd al-suʿūd, which is partly preserved (and was perhaps never completed). The latter work contains detailed information on some of the books Ibn Tawus had in his possession, together with extensive quotations from those books.31 The Ottoman Muʾayyadzade ʿAbd al-Rahman Efendi, a close friend and confidant of the future Ottoman sultan Bayazid II (r. 1481–1516), assembled an impressive personal library with an estimated seven thousand volumes. A six-folio partial inventory of his library, listing some 2,100 titles, is extant in manuscript.32 Bayazid II also commissioned an inventory of books held in the library of the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. The inventory, dated 1503–4, records over seven thousand titles.33 The Hanbali Damascene scholar Ibn ʿAbd al-Hadi (d. 1503) compiled a catalogue of his library, comprising close to three thousand titles.34 An endowment deed dated 1751 records the donation of a private book collection of more than one hundred volumes by the otherwise unknown al-Hajj al-Sayyid Mustafa b. al-Hajj Efendi.35 From the early nineteenth century, the inventory of the private collection––amounting to almost 1,200 volumes––of the founder of the Khalidiyya branch of the Naqshbandiyya order in Damascus, Sheikh Khalid al-Shahrazuri al-Naqshabandi (d. 1827), which was compiled on the occasion of a lawsuit involving the collection, has come down to us.36 These are but a few examples.

Closely related to catalogues and inventories of library collections are notebooks containing detailed descriptions of works and excerpts from them, many of which are otherwise lost. A prominent example is the Kitāb al-Funūn by the Hanbali author Ibn ʿAqil (d. 1119), a personal notebook consisting of quotations from works by others together with the author’s own comments and thoughts on the material. The book is only partly extant in a single manuscript and is believed to have consisted of two hundred or more volumes in its original form. Another example of an entirely different character is the Tadhkira, a literary notebook by the Hanafi littérateur and historian Kamal al-Din ʿUmar b. Ahmad Ibn al-ʿAdim (d. 1262).37

Following Ibn Tawus, the tradition of compiling catalogues with extensive excerpts from the books being described was continued among Shiʿite scholars, particularly among those from al-Hilla, Ibn Tawus’s hometown, located some one hundred kilometers south of Baghdad. Ibrahim b. ʿAli b. al-Hasan al-Kafʿami (d. 1499/1500), who resided both in al-Hilla and Najaf, compiled Majmūʿ al-gharāʾib wa-mawḍūʿ al-raghāʾib, listing the books he had access to and quoting extensively from them. Collections of selections gleaned from––now often lost––books and manuscripts also circulated under the title Fawāʾid, as in the case of a notebook by the Twelver Shiʿi Iranian scholar ʿAbd Allah al-Afandi al-Isfahani (d. 1718), the author of a biographical dictionary titled Riyāḍ al-ʿulamāʾ, who provides information in the notebook that often complements the data provided in the dictionary. Mention should also be made of the various excerpts (fawāʾid) from earlier philosophical works by the Jewish philosopher ʿIzz al-Dawla Ibn Kammuna (d. circa 1284), compiled for his own study purposes.38 The Iraqi Shiʿi scholar and politician Muhammad Rida al-Shabibi (d. 1965) also produced copies and excerpts of many of the manuscripts he inspected during his study sojourns in various libraries, as is the case with the notes he took during a visit to the Rawda al-Haydariyya in Najaf in 1911, which are extant in manuscript.39

The Interplay of Oral and Written Culture and the Predominance of a Writerly Culture in Islamic Societies

The reasons for the eminent status of the written word and the development of the codex include the early codification of the Qurʾan and its central place in Islamic practice, its continuous transmission through carefully produced copies, and the ubiquity of Qurʾanic passages in the visual cultures of the Islamic world, in addition to its oral recitation and aural consumption. At the same time, the reports and utterances of the Prophet Muhammad, the sunna, also held a prominent position among Muslims from early on. The codification of the prophetic traditions was concluded only centuries later, privileging orality/aurality over written transmission during the first centuries of Islam.

The shift from a nonliterate mode to a literate one, from oral to written transmission, or rather to a combination of oral/aural and literary practices, is commonly dated to the ninth century, and the ways in which oral/aural and written practices interacted and complemented each other is another vibrant field of scholarship.40 The interplay between oral/aural and writerly culture gave rise to a variety of literary genres and documentary sources, which provide important information about literary cultural production among Muslims (fig. 5.8). The backbone of oral transmission was a solid chain of transmitters to guarantee the authenticity of the transmitted content, especially in view of the canonical status of the sunna.

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8Within the larger context of Sunnism, a number of literary genres emerged, reflecting the changing landscape of traditional ḥadith scholarship during the canonical (ninth and tenth centuries) and postcanonical periods (eleventh century and beyond) and related social practices. Among other purposes, they evolved into an efficient means for documenting the internal scholarly tradition, often including extensive booklists.41 The starting point in the organizational structure of such works was the list of transmitters with whom a scholar or collector of ḥadith had studied over the course of his or her life. From the ninth century onward, Sunni ḥadith scholars compiled catalogues of their sheikhs, and the two genres that were most popular among scholars of the eastern and central lands of Islam were the mashyakha and the muʿjam al-shuyūkh. The entries in this type of book characteristically consist of two core elements—the names of the transmitters with whom the sheikh in question studied and some sample ḥadith from the sheikh.

From about the eleventh century onward, compilers of mashyakhas and muʿjams increasingly focused on their transmitters and/or chains of transmission for the books they had studied, often going beyond the narrow confines of ḥadith literature and applying the practice to the whole array of disciplines of learning. Such books were arranged sometimes according to book title, sometimes by the name of the transmitters. The Egyptian Shafiʿi scholar Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalani (d. 1449), for example, provides an inventory of his teachers and the books he studied in a series of works, viz. his al-Muʿjam al-mufahris (arranged according to book title) and al-Majmaʿ al-muʾassis li-l-Muʿjam al-mufahris (arranged by transmitters).

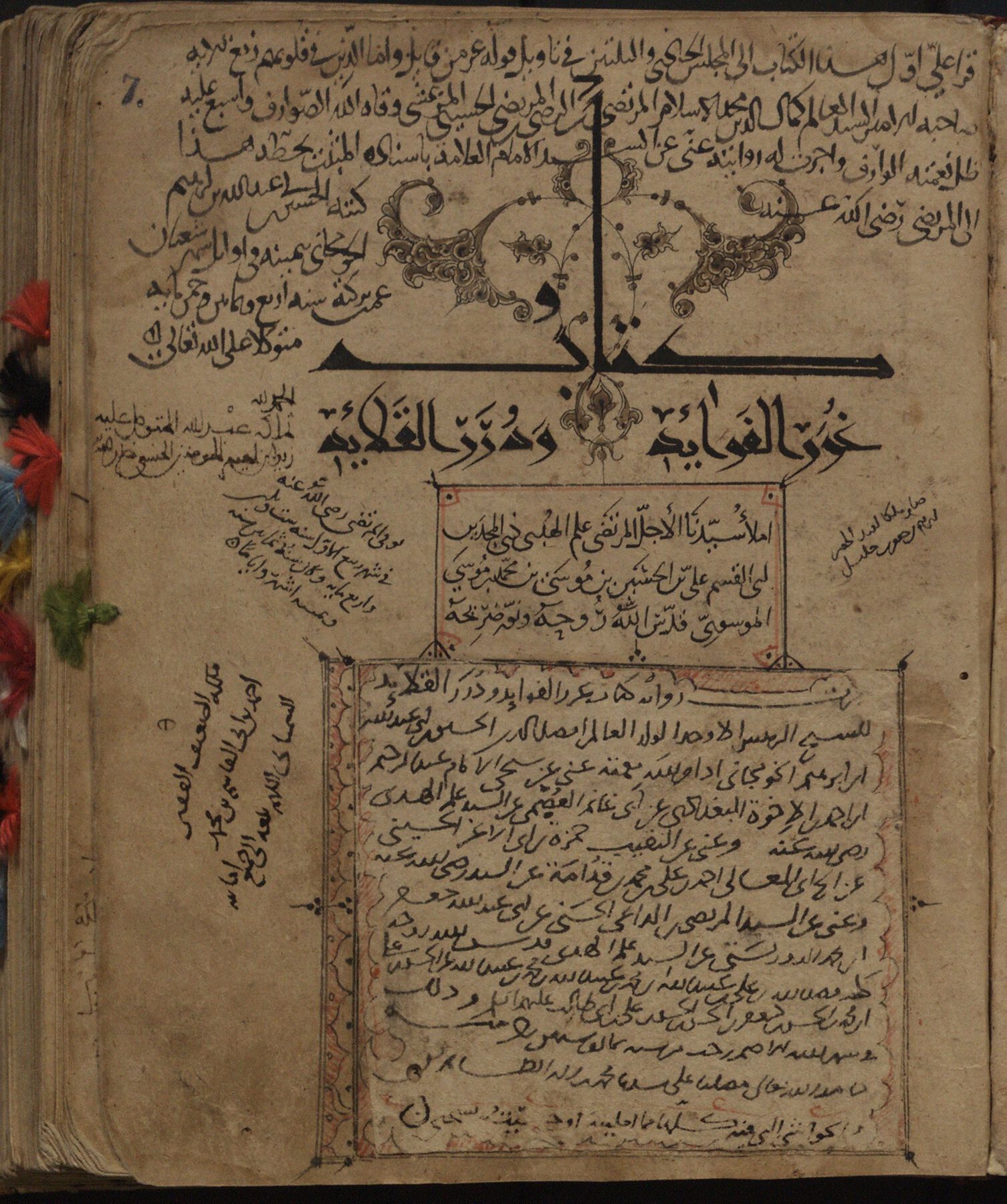

With respect to the early modern period, mention should be made of al-Nafas al-Yamanī wa-l-rawḥ al-rayḥānī fī ijāzāt Banī l-Shawkānī by the Shafiʿi scholar of the Yemeni town of Zabid, Wajih al-Din ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Sulayman al-Ahdal (d. 1835), detailing his teachers and the chains of transmission for the books he studied with them. The overall structural framework of al-Nafas al-yamanī is an ijāza, or “license to transmit,” issued by ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Ahdal to members of the family of the Yemeni scholar Muhammad b. ʿAli al-Shawkani (d. 1834). Al-Shawkani, in turn, provides in his Itḥāf al-akābir bi-isnād al-dafātir the chains of authority for each book title he mentions.

Presenting chains of transmission for books became particularly popular among scholars in the Islamic west, with compilations that were typically referred to as fihrist, fahrasa, barnāmaj, or thabat, a genre whose beginnings can be dated to the late tenth century. Among the earliest extant examples is Abu Muhammad ʿAbd al-Haqq Ibn ʿAtiyya’s (d. 1147) Fahrasa, while the Fahrasa of the Andalusi scholar Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Khayr al-Ishbili (d. 1179) is the first work in which the material is arranged according to discipline. The fihrist by Abu l-ʿAbbas Ahmad b. Yusuf al-Fihri al-Labli (d. 1291), known as Fihrist al-Lablī, is an example of a work within this genre containing extensive material on the Ashʿarite tradition. The “license to transmit” played a central role also among the Shiʿites, and in many ways it resembles in structural organization and social functions the various genres for documenting transmission that prevailed among the Sunnis. Although the earliest extant ijāzas date from the tenth century, more detailed ones have been increasingly issued over the centuries. Arranged as a rule according to transmitters, such documents include detailed bibliographical information on the books the recipient of an ijāza (the mujāz) has studied in one or often several disciplines of learning, thus providing a comprehensive picture of the literary canon that was available to the scholar. Moreover, an essential function of comprehensive, text-independent ijāzas is the documentation of the scholarly tradition, first and foremost the scholars making up the chains of transmission of the scholar granting the ijāza (the mujīz). This type of ijāza often fulfills functions similar to those of biographical dictionaries, and in many cases the boundary between the two genres is blurred. A prominent example is the Kitāb al-Wajīz by the prominent Shafiʿi transmitter Abu Tahir Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Silafi (d. 1180), an inventory of scholars from whom he received an ijāza (and whom he knew only through correspondence) with detailed, and often unique, biobibliographical information about each.

Imamis and Zaydis also compiled collections of ijāzas, many of which contain dozens or even hundreds of such documents. Taken together, these provide detailed insights into the scholarly tradition and its literary output over the course of several centuries. Mention should be made, by way of example, of the collection of ijāzas that was granted to Ayat Allah al-ʿUẓma Shihab al-Din al-Husayni al-Marʿashi al-Najafi (d. 1990) over his lifetime, compiled by his son, al-Sayyid Mahmud al-Marʿashi. Among the Zaydis, Majmūʿ al-ijāzāt, a collection of dozens of ijāzas that Ahmad b. Saʿd al-Din al-Maswari (d. 1668) culled from the manuscripts available to him, is transmitted in several manuscripts.

Muslim Scholarly Practices throughout the Centuries

The eminent status of the written tradition also gave rise from early on to scholarly methods among Muslims that in many ways predate some of the text-critical approaches of modern scholarship. A first attempt at analysis was Franz Rosenthal’s The Technique and Approach of Muslim Scholarship (1947). Toward the end of the twentieth century, systematic analysis in this area of scholarship boomed. The principal directions, which are closely related to each other, include, first of all, codicology and manuscript studies, a field that has blossomed over the past few decades, as is evident from the growing number of handbooks,42 specialized journals,43 book series,44 and research initiatives45 produced. This has led to a deeper appreciation of paratextual materials found in manuscripts, which in turn has prompted scholars to combine aspects of intellectual and social history to study, for example, not only the intellectual contents of the codices and the social practices of the producers of knowledge (the scholars and the authors), but also the habits, interests, and practices of the consumers of knowledge, the readers (fig. 5.9). The increased consultation of documentary sources, such as endowment deeds and library registers, has made possible a growing number of studies devoted to individual libraries, a new focus that is complemented by studies on the collections brought together by Western collectors and preserved today in European and North American libraries.46

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.9The following examples, randomly chosen, provide a taste of Muslim scholarly practices throughout the centuries, focusing on critical editions, referencing, and the continuation of the manuscript culture into the twentieth century. First, in terms of critical editions, the twelfth-century Shiʿite scholar Fadl Allah b. ʿAli al-Rawandī al-Kashani was the most important transmitter of the writings of two prominent Twelver Shiʿite scholars and officials in tenth- and eleventh-century Baghdad, the brothers al-Sharif al-Murtada ʿAli b. al-Husayn al-Musawi and al-Sharif al-Radi Muhammad b. al-Husayn al-Musawi.47 Of their writings, the most important were al-Murtada’s Kitāb al-Ghurar, a book containing a variety of exegetical and literary materials divided into sessions (majālis), which was popular among both Shiʿis and Sunnis, and the Kitāb Nahj al-balāgha, a collection of utterances of semicanonical status attributed to ʿAli b. Abi Talib, compiled by al-Sharif al-Radi. The majority of extant copies of these works were transmitted through Fadl Allah, with his name showing up in nearly all chains of transmission. The rigorous editorial principles Fadl Allah applied are documented, for example, in Ms. Istanbul, Süleymaniye, Reisülküttab 53, transcribed by Muhammad b. Aws b. Ahmad b. ʿAli b. Hamdan al-Rawandi (dated 1170). The scribe explains that he had a copy in the possession of Fadl Allah al-Rawandī as antigraph, written in the hand of Ibn Ikhwa (d. 1153), Fadl Allah’s teacher, and he quotes Fadl Allah’s colophon in full. In it, Fadl Allah explains the editorial principles he followed when working on his copy: he collated it with two other copies, one of them transcribed by a direct student of al-Murtadā. In addition, Fadl Allah reports that he consulted the relevant collections of poetry to render properly the poetry included in the Ghurar. The manuscript also contains copious marginal glosses and corrections, indicating a similarly careful transcription process, and many of these originated with Fadl Allah. They include, for example, comments in which Fadl Allah recorded different copies of source texts that he had consulted; mentions of alternative interpretations or additional perspectives derived from his own studies, with precise details; and references to other works containing elaborations relevant to the discussion at hand (fig. 5.10). Fadl Allah excelled as a critical editor of and commentator on other works as well, notably the K. al-Ḥamāsa, an anthology of poetry by Abu Tammam Habib b. Aws al-Taʾi (d. 842/45). Fadl Allah’s revised edition of the Ḥamāsa, together with his glosses, is preserved in a single manuscript held by the British Library.

Figure 5.10

Figure 5.10On the second issue of Muslim scholarly practices throughout the centuries discussed here, referencing—the authorial practice of indicating the sources that one has consulted when composing a book, either in a separate bibliographical section or throughout the book and typically including the chains of transmission—is encountered from very early on. The Sunni scholar Ibn Abi l-Hatim al-Razi (d. 938) lists his sources at the beginning of his Qurʾan exegesis, while the Twelver Shiʿite scholar Muhammad b. ʿAli Ibn Babawayh (d. 991) concludes his ḥadith work Man lā yaḥḍuruhu l-faqīh with a chapter discussing his sources. The Andalusi scholar Abu ʿAbd Allah Muhammad al-Qurtubi (d. 1104) appended to his Kitāb Aqḍiyat rasūl Allāh a list of the books he had consulted; Abu Ishaq Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Thaʿalabi (d. 1035/36) mentions in the introduction to his Qurʾan exegesis, al-Kashf wa-l-bayān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān, all the works he used while composing the work; and a list of sources is also provided by Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Dhahabi (d. 1348) in his renowned Tārīkh al-Islam. Another example is the Hanafi scholar of Bukhara, Uzbekistan, ʿImad al-Din Mahmud al-Faryabi (d. 1210/11), who completed in 1200 his Kitāb Khāliṣat al-ḥaqāʾiq wa-niṣāb ghāʾiṣat al-daqāʾiq, a book on piety, ethics, and moral conduct, which concluded with a bibliography of sources; it is one of the earliest works, by the way, in which the author does not indicate his chains of transmission for the named sources. The Kitāb al-Baḥr al-muḥīṭ fī uṣūl al-fiqh, an important work on legal theory by the Shafiʿite scholar Badr al-Din Muhammad b. Bahadur al-Shafiʿi al-Zarkashi (d. 1392), also opens with a section in the course of which he lists his sources. Since many of the books al-Zarkashi used no longer exist, his often elaborate quotations allow at least a partial reconstruction of what has been lost. An exceptional example is the aforementioned Ibn Tawus, who, throughout his writings, documents his sources with great accuracy, often indicating the volume, quire, or even folio or page of the codex he is quoting.48

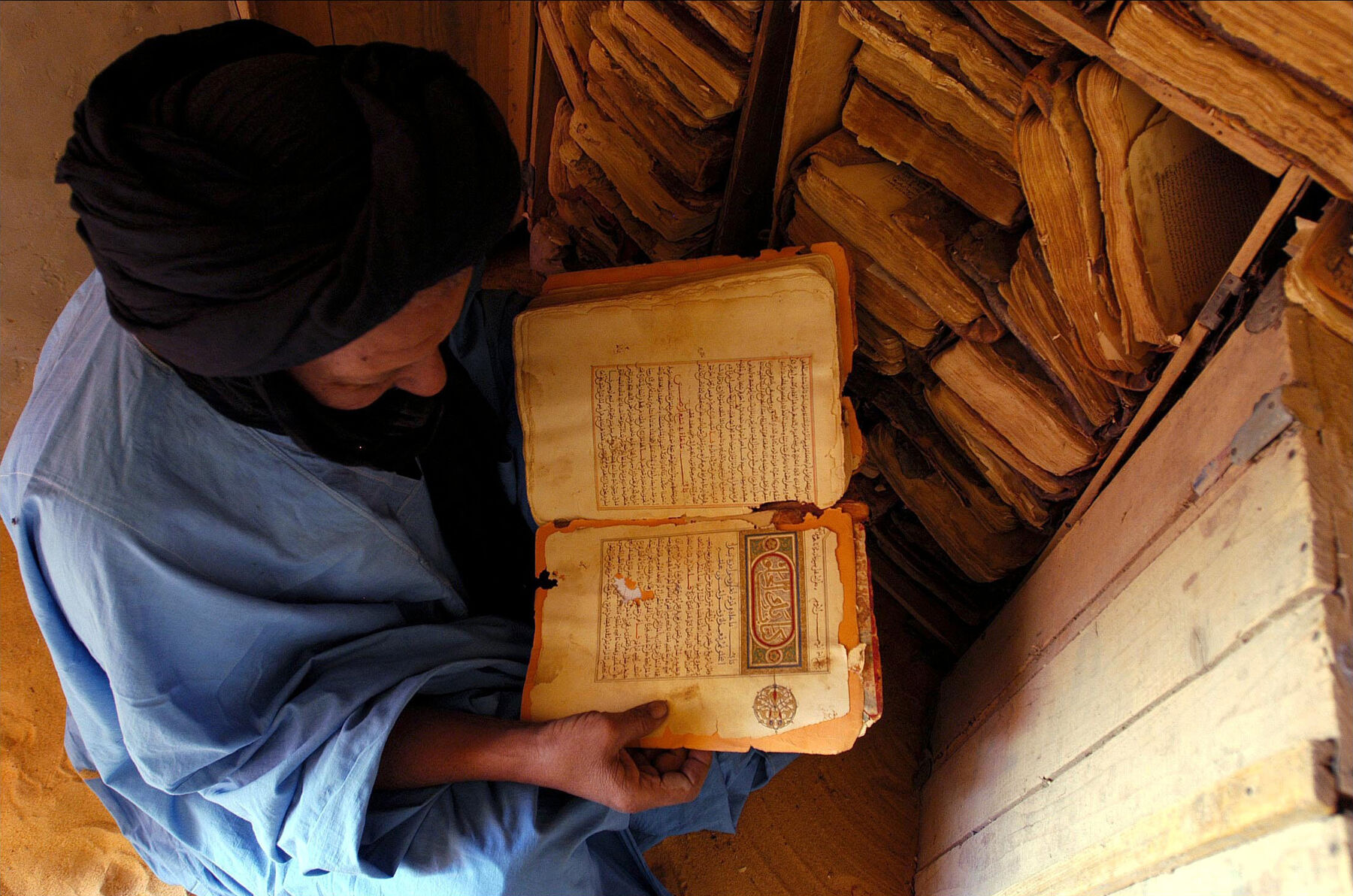

On the third issue of Muslim scholarly practices throughout the centuries, in many parts of the Islamic world we can observe an extraordinary continuity of manuscript culture, which has even persisted into the twenty-first century. While the reason is evident for countries with poor technological infrastructure, such as Yemen, there were and are many other reasons for this phenomenon, such as the desire to evade censorship, which can easily be applied to printed works but is impossible to enforce on the transcription of manuscripts.49 Most importantly, however, the production of manuscripts, as contrasted with printed works, was perceived as a pious exercise.

Many modern scholars and scribes in contrast have also pursued scholarly purposes when transcribing books of earlier times by hand. Mention should be made, by way of example, of the Iraqi scholar Muhammad b. Tahir b. Habib al-Samawi (d. 1950). Al-Samawi hailed from Samawa in southern Iraq, and he spent several decades in Najaf, one of the most important intellectual centers of Twelver Shiʿism, in pursuit of scholarship. Al-Samawi was an avid collector of manuscripts who transcribed hundreds of Shiʿite and non-Shiʿite texts for his personal library. Many of his transcriptions are apographs of copies held by the Rawḍa al-Haydariyya, one of the oldest libraries of Iraq. In his colophons he typically identifies his antigraphs, fully quoting their colophons and commenting on their quality and, accordingly, on his own contribution during the transcription and editing of the text.50

Islamic Manuscript Culture under Threat

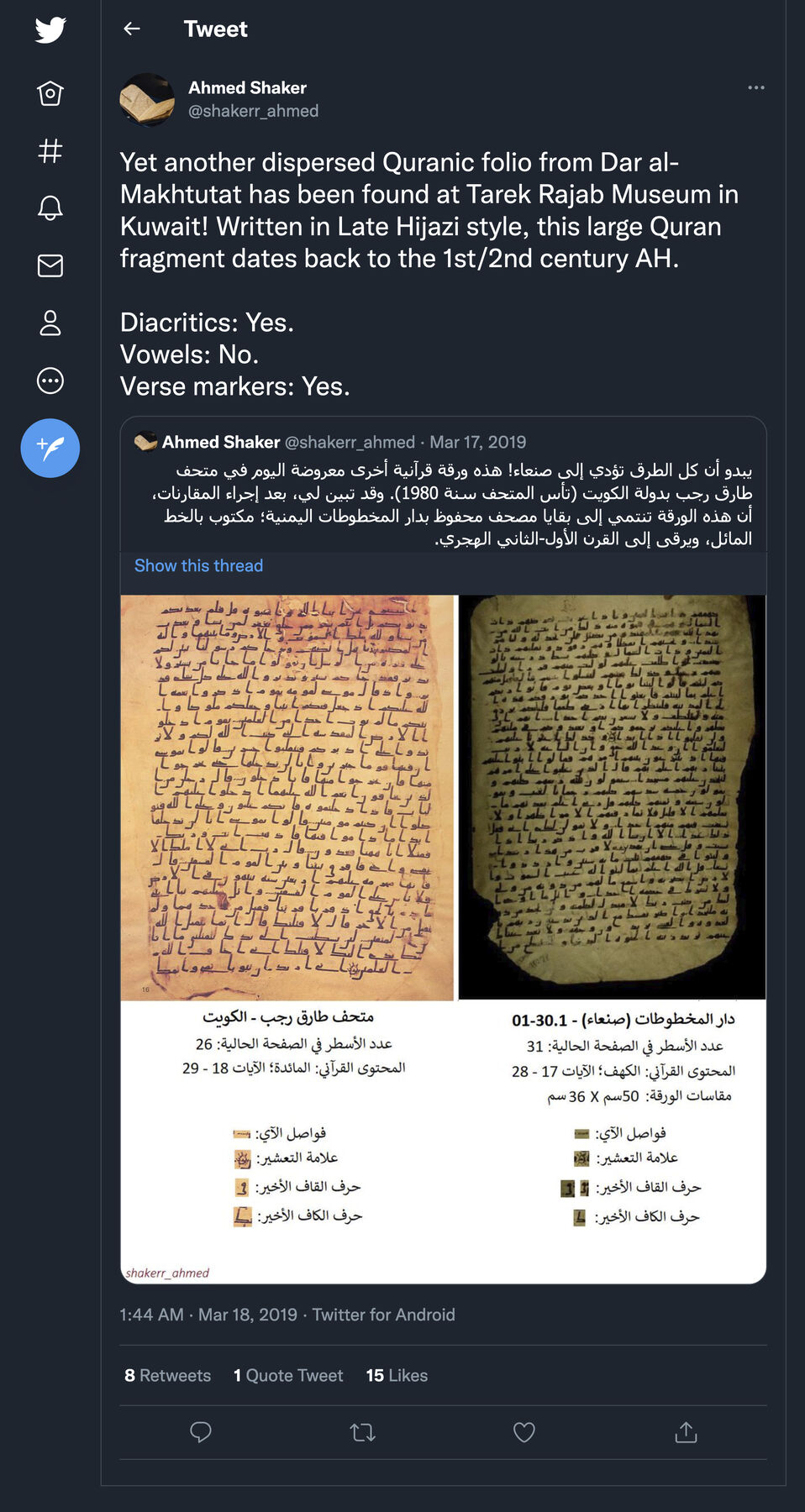

There are many reasons why a certain book has come down to us while others fall into oblivion and eventually get lost. What becomes part of the canon at any given time and what is discarded is continuously renegotiated, and many of the registers discussed above not only record what was there but also silently exclude what was meant to be left out.51 At the same time, Islamic manuscript heritage continues to be threatened in many ways—exposed to improper handling, exposure, theft, inclement climatic conditions, and willful destruction, to name a few dangers. Over the past few decades, there have been repeated cases of deliberate destruction of Islamic manuscripts. They include the bombing of libraries, archives, and museums in Kosovo and Bosnia by Serbian nationalists, most importantly the tragic burning of the National Library of Bosnia-Herzegovina in August 1992, when some two million books were destroyed by fire.52 Moreover, a large portion of the manuscript holdings of the libraries of Iraq was either destroyed or looted in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War and again in March 2003, following the invasion of Iraq by American and British troops (fig. 5.11).53 It is also worrying that Islamic manuscripts of uncertain provenance continue to be auctioned off into private hands.54 Sectarianism and multiple forms of censorship pose another threat to Islamic cultural heritage. Reducing the intellectually rich and diverse Islamic literary heritage to the bare minimum of what is seen as allegedly authentic is a strategy that is characteristic of Wahhabism, Salafism, and jihadism, and their proponents. Whatever goes against their interpretation of Islam is classified as “heretical” and banned from distribution (fig. 5.12). Moreover, libraries holding books and manuscripts that are seen as containing deviant views are targeted for destruction, and the same holds for historical monuments, shrines, and religious sites, which have been destroyed over the past several decades by Muslim extremists in an attempt to “purify” Islam (fig. 5.13). Particular mention should be made of the attempts by Islamic militants to destroy important manuscript holdings in Timbuktu, Mali, in 2013; the destruction of cultural heritage in Sukur, Nigeria, in 2015;55 the destruction of books and manuscripts in the libraries of Mosul at the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS, also known as ISIL or Da’esh) in 2015; and attacks on Zaydi libraries in Yemen (fig. 5.14).

Figure 5.11

Figure 5.11 Figure 5.12

Figure 5.12 Figure 5.13

Figure 5.13 Figure 5.14

Figure 5.14Biography

- Sabine SchmidtkeSabine Schmidtke is professor of Islamic intellectual history in the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. Her research interests include Shiʿism (Zaydism and Twelver Shiʿism), intersections of Jewish and Muslim intellectual history, the Arabic Bible, the history of Orientalism and the Science of Judaism, and the history of the book and libraries in the Islamicate world. Her recent publications include Muslim Perceptions and Receptions of the Bible: Texts and Studies (2019), with Camilla Adang; Traditional Yemeni Scholarship amidst Political Turmoil and War: Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl b. al-Muṭahhar al-Manṣūr (1915–2016) and His Personal Library (2018); and The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Philosophy (2017), coedited with Khaled el-Rouayheb.

Suggested Readings

- Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, Al-Šarīf al-Murtaḍā’s Oeuvre and Thought in Context: An Archaeological Inquiry into Texts and Their Transmission (Córdoba: Córdoba University Press, 2022).

- Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, “Bibliographical Practices in Islamic Societies, with an Analysis of MS Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Hs. or. 13525,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 4, nos. 1–2 (2016): 102–51.

- Jonathan M. Bloom, From Paper to Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001).

- François Déroche et al., Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script (London: al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 2015).

- Beatrice Gründler, The Rise of the Arabic Book (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020).

- Konrad Hirschler, The Written Word in the Medieval Arabic Lands: A Social and Cultural History of Reading Practices (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012).

Notes

Al-Maktaba al-Shāmila, https://shamela.ws. For a short history, see Peter Verkinderen, “Al-Maktaba al-Shāmila: A Short History,” Knowledge, Information Technology, & the Arabic Book (KITAB), 3 December 2020, https://kitab-project.org/Al-Maktaba-al-Shāmila-a-short-history/. ↩︎

Noor Digital Library, http://www.noorlib.ir. ↩︎

PDF Books Library, http://alfeker.net. ↩︎

Shia Online Library, http://shiaonlinelibrary.com. ↩︎

Al-Maktaba al-Waqfiyya, https://waqfeya.net. ↩︎

See “Islamic Manuscript Studies: Resources for the Study of Manuscripts Produced in the Islamic World and the Manuscript Cultures They Represent,” curated by Evyn Kropf, University of Michigan Library, https://guides.lib.umich.edu/c.php?g=283218&p=1886652. ↩︎

Süleymaniye Library, http://yazmalar.gov.tr/sayfa/manuscript-books/9. ↩︎

Jan Just Witkam, “Introduction by Jan Just Witkam,” in Brockelmann Online, https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brockelmann/introduction-by-jan-just-witkam-COM_001. ↩︎

Carl Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur, vol. 1 (1898), 1 (“alle Erzeugnisse des menschlichen Geistes . . . die in sprachliche Form gekleidet sind”). The English translation of the phrase is taken from Witkam, “Introduction by Jan Just Witkam.” ↩︎

See Encyclopaedia Iranica, s.v. “Storey, Charles Ambrose,” by Yuri Bregel, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/storey-charles-ambrose. ↩︎

Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur, vol. 1, iii–vii, 3–6. ↩︎

Brockelmann, iii. The English translation of the phrase is again taken from Witkam, “Introduction by Jan Just Witkam.” ↩︎

See Brockelmann, 4–5 for the first edition, and Brockelmann, 4–13 for the updated edition. ↩︎

See Geoffrey Roper, World Survey of Islamic Manuscripts, 4 vols. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 1992–94), https://brill.com/view/serial/9ROP. ↩︎

The contents of the World Survey of Islamic Manuscripts are also accessible from the al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, https://digitallibrary.al-furqan.com/world_library. This is based on the Survey but has some added value, including an interactive map to access information about the various manuscript libraries. ↩︎

See “Brockelmann: The History of Arabic Literary Culture,” https://brill.com/view/package/brob?language=en. ↩︎

See also, for example, Max Krause’s review, published in Der Islam 24 (1937): 307–11, of Brockelmann’s first supplementary volume of 1937, with a list of corrections and additions to 539 entries in Brockelmann’s work. ↩︎

See Oriental Manuscript Resource (OMAR), http://omar.ub.uni-freiburg.de/. ↩︎

IslHornAfr, http://www.islhornafr.eu/index.html. ↩︎

Knowledge, Heresy and Political Culture in the Islamic West: Eighth–Fifteenth Centuries (KOHEPOCU), http://kohepocu.cchs.csic.es/. ↩︎

HUNAYNNET, https://hunaynnet.oeaw.ac.at. ↩︎

See, “Bibliotheca Arabica: Towards a New History of Arabic Literature,” Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities, https://www.saw-leipzig.de/de/projekte/bibliotheca-arabica/intro. ↩︎

KITAB, http://kitab-project.org/. ↩︎

Maxim Romanov, “Cultural Production in the Islamic World,” al-Raqmiyyāt, last updated 14 October 2017, https://alraqmiyyat.github.io/2017/10-14.html. ↩︎

A term coined by François Déroche, Le livre manuscrit arabe: Préludes a une histoire (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2004), 44. See also Beatrice Gründler, The Rise of the Arabic Book (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 2. Jonathan Bloom describes the same phenomenon as an “explosion of books and book learning.” See Jonathan M. Bloom, From Paper to Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 110. ↩︎

Paul E. Walker, “Libraries, Book Collection and the Production of Texts by the Fatimids,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 4, nos. 1–2 (2016): 7–21. ↩︎

Letizia Osti, “Notes on a Private Library in Fourth/Tenth-Century Baghdad,” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 12 (2012): 215–23. ↩︎

Miklos Muranyi, “Geniza or Ḥubus: Some Observations on the Library of the Great Mosque in Qayrawān (Tunisia),” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 42 (2015): 183–99. ↩︎

Konrad Hirschler, Medieval Damascus: Plurality and Diversity in an Arabic Library (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016). ↩︎

Sabine Schmidtke, “Notes on an Arabic Translation of the Pentateuch in the Library of the Twelver Shīʿī Scholar Raḍī al-Dīn ʿAlī b. Mūsā Ibn Ṭāwūs (d. 664/1266),” Shii Studies Review 1, nos. 1–2 (March 2017): 72–129. ↩︎

Judith Pfeiffer, “Emerging from the Copernican Eclipse: The Mathematical and Astronomical Sciences in Müʾeyyedzade ʿAbdurrahman Efendi’s Private Library (fl. ca. 1480–1516),” in The 1st International Prof. Dr. Fuat Sezgin Symposium on History of Science in Islam Proceedings Book, ed. Mustafa Kaçar, Cüneyt Kaya, and Ayşe Zişan Furat (Istanbul: Istanbul University Press, 2019), 151–91. ↩︎

Treasures of Knowledge: An Inventory of the Ottoman Palace Library (1502/3–1503/4), vol. 1: Essays, vol. 2: Transliteration and Facsimile “Register of Books” (Kitāb al-kutub), Ms. Török F. 59; and Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Könyvtára Keleti Gyűjtemény (Oriental Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences), series: Muqarnas, supplements, vol. 14, ed. Gülru Necipoğlu, Cemal Kafadar, and Cornell H. Fleischer (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2019). ↩︎

Konrad Hirschler, A Monument of Medieval Syrian Book Culture: The Library of Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020). ↩︎

Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, “Bibliographical Practices in Islamic Societies, with an Analysis of MS Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Hs. or. 13525,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 4, nos. 1–2 (2016): 102–51. ↩︎

Frederik de Jong and Jan Just Witkam, “The Library of al-Šayḵ Ḵālid al-Šahrazūrī al-Naqšbandī (d. 1242/1827): A Facsimile of the Inventory of His Library (Ms Damascus, Maktabat al-Asad, No. 259),” Manuscripts of the Middle East 2 (1987): 68–87. ↩︎

Fuat Sezgin, ed., The Literary Notebook Tadhkira by Ibn al-ʿAdīm Kamāl al-Dīn ʿUmar ibn Aḥmad (d. 1262 A.D.) (Frankfurt: Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science, 1992). ↩︎

Reza Pourjavady and Sabine Schmidtke, A Jewish Philosopher of Baghdad: ʿIzz Al-Dawla Ibn Kammāna (d. 683/1284) and His Writings (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2006). ↩︎

Sabine Schmidtke, “Saʿd b. Manṣūr Ibn Kammūna’s Writings and Transcriptions in the Maktabat al-Rawḍa al-Ḥaydariyya, Najaf: Preservation, Loss, and Recovery of the Philosophical Heritage of Muslims and Jews,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, published online 25 June 2021; forthcoming in print), https://doi.org/10.1163/2212943X-bja10003. ↩︎

Recent important studies include Shawkat Toorawa, Ibn Abī Ṭāhir Ṭayfūr and Arabic Writerly Culture: A Ninth-Century Bookman in Baghdad (London: Routledge, 2005); Konrad Hirschler, The Written Word in the Medieval Arabic Lands: A Social and Cultural History of Reading Practices (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012); and Gründler, Rise of the Arabic Book. Mention should also be made of Gregor Schoeler’s seminal studies, including his Écrire et transmettre dans les débuts de l’islam (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2002). ↩︎

The majority of examples are discussed in some more detail in Ansari and Schmidtke, “Bibliographical Practices in Islamic Societies.” See also Garrett A. Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition: A Social and Intellectual History of Hadith Transmission across a Thousand Years (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2020). ↩︎

E.g., Adam Gacek, Arabic Manuscripts: A Vademecum for Readers (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2009); and François Déroche et al., Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script (London: al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 2015). Important is also the oeuvre of Jan Just Witkam: see Robert M. Kerr and Thomas Milo, “List of Publications of Prof. JJ Witkam,” in Writings and Writing: From Another World and Another Era, ed. Robert M. Kerr and Thomas Milo (Cambridge: Archetype, 2010), xv. Needless to say, pathbreaking contributions to this field have also been made by scholars writing in languages other than English, especially Persian and Arabic. ↩︎

E.g., Journal of Islamic Manuscripts and Manuscripta Orientalia. ↩︎

E.g., Islamic Books and Manuscripts (by Brill). ↩︎

E.g., the Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies (COMSt) network, hosted by the University of Hamburg. ↩︎

See, e.g., Boris Liebrenz and Christoph Rauch, eds., Manuscripts, Politics and Oriental Studies: Life and Collections of Johann Gottfried Wetzstein (1815‒1905) in Context (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2019); Sabine Mangold-Will, Christoph Rauch, and Siegfried Schmitt, eds., Sammler, Bibliothekare, Forscher: Zur Geschichte der orientalischen Sammlungen an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 2022). ↩︎

For a detailed study of Faḍl Allāh al-Rāwandī and his role as transmitter of the K. al-Ghurar by al-Murtaḍā, see Hassan Ansari and Sabine Schmidtke, Al-Šarīf al-Murtaḍā’s Oeuvre and Thought in Context: An Archaeological Inquiry into Texts and Their Transmission (Córdoba: Córdoba University Press, 2022), chapter 1.4. ↩︎

It is on the basis of the detailed information Ibn Tawus provides throughout his oeuvre that the contents of his library have been reconstructed. See Etan Kohlberg, A Medieval Muslim Scholar at Work: Ibn Ṭāwūs and His Library (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 1992). ↩︎

See, e.g., Sabine Schmidtke, Traditional Yemeni Scholarship amidst Political Turmoil and War: Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl b. al-Muṭahhar al-Manṣūr (1915–2016) and His Personal Library (Córdoba: Córdoba University Press, 2018), 41 n.138. ↩︎

For other examples of scholars engaged in the transcription of manuscripts during the twentieth century, see Ansari and Schmidtke, Al-Šarīf al-Murtaḍā’s Oeuvre, chapter 2.4. ↩︎

This is a complex question, the methodological consequences of which are discussed in Arnold Esch, “Überlieferungs-Chance und Überlieferungs-Zufall als methodisches Problem des Historikers,” Historische Zeitschrift 240, no. 3 (1985): 529–70. ↩︎

Anna Burgess, “Harvard Librarian Puts This War Crime on the Map,” Harvard Gazette, 21 February 2020, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/02/harvard-librarian-puts-this-war-crime-on-the-map/. ↩︎

See Ian M. Johnson, “The Impact on Libraries and Archives in Iraq of War and Looting in 2003: A Preliminary Assessment of the Damage and Subsequent Reconstruction Efforts,” International Information & Library Review 37, no. 3 (2005): 209–71; D. Vanessa Kam, “Cultural Calamities: Damage to Iraq’s Museums, Libraries, and Archaeological Sites during the United States–Led War on Iraq,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 23, no. 1 (2004): 4–11; Nabil al-Tikriti, “‘Stuff Happens’: A Brief Overview of the 2003 Destruction of Iraqi Manuscript Collections, Archives, and Libraries,” Library Trends 55, no. 3 (2007): 730–45; and Geoffrey Roper, “The Fate of Manuscripts in Iraq and Elsewhere,” Muslim Heritage, 11 September 2008, https://muslimheritage.com/fate-of-manuscripts-iraq-elsewhere/. ↩︎

For examples see Sabine Schmidtke, “For Sale to the Highest Bidder: A Precious Shiʿi Manuscript from the Early Eleventh Century,” Shii Studies Review 4, nos. 1–2 (2020): 184–93, and “Saʿd b. Manṣūr Ibn Kammūna’s Writings.” ↩︎

Akeem O. Bello, “Countering Boko Haram Insurgency: Investigating Culture Destruction Attempts and Culture Conservation Efforts in North-Eastern Nigeria,” paper presented at the “African Heritage and the Pillars of Sustainability” summer school, July 2016 (updated 2017), https://heritagestudies.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/4.4-ABello_final_clean_13.10.pdf. ↩︎