In recent years, nanocellulose-based products and multilayered nanoparticles have emerged as new solutions for the consolidation of canvas-supported paintings. This paper focuses on these recently developed treatments as applied in the framework of the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 project Nanorestart. It provides a summary of their properties, advantages, and disadvantages in terms of ease of application, reinforcement provided, visual appearance, and stability. Physicochemical and mechanical results of the tests performed in the past couple of years are presented. The treatments can be divided into three categories—pure nanocellulose, nanocomposite, and multilayered nanoparticles—characterized by different compositions, degrees of penetration, and modes of consolidation. This project has used a systematic multiscale approach to review the potential of new consolidants for the structural consolidation of canvas-supported paintings. An overall account of the benefits of each consolidation approach is presented on the basis of previously published work. It is anticipated that these treatments will offer an alternative to lining and consolidants currently in use and prevent the recurrence of the issues highlighted at the Greenwich conference.

27. Nanocellulose and Multilayered Nanoparticles in Paintings Conservation: Introduction of New Materials for Canvas Consolidation and a Novel Multiscale Approach for Their Assessment

- Alexandra Bridarolli, Eastman Dental Institute, University College London

- Marianne Odlyha, Department of Biological Sciences, Birkbeck College, London

- Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Krzysztof Kolman, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Romain Bordes, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Krister Holmberg, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Gema Campo-Francés, Facultat Belles Arts, University of Barcelona

- Cristina Ruiz-Recasens, Facultat Belles Arts, University of Barcelona

- Manfred Anders, Zentrum fur Bucherhaltung, Leipzig, Germany

- Aurélia Chevalier, Aurelia Chevalier Atelier, Paris

- Piero Baglioni, Department of Chemistry and Center of Colloid and Nanoscience (CSGI), University of Florence

- Laurent Bozec, Eastman Dental Institute, University College London; Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto

- Giovanna Poggi, Department of Chemistry and Center of Colloid and Nanoscience (CSGI), University of Florence

Introduction

Recently, new developments in paintings conservation have seen the introduction of nanocellulose (NC; nano-size clusters of cellulose chains) and multilayered nanoparticles as more compatible treatments for the consolidation and deacidification of canvases of modern and contemporary paintings (Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.; Xu, Q., G. Poggi, C. Resta, M. Baglioni, and P. Baglioni. 2020. “Grafted Nanocellulose and Alkaline Nanoparticles for the Strengthening and Deacidification of Cellulosic Artworks.” Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 576: 147–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2020.05.018.; Baglioni, Piero, David Chelazzi, Rodorico Giorgi, and Giovanna Poggi. 2013. “Colloid and Materials Science for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Cleaning, Consolidation, and Deacidification.” Langmuir 29, no. 17: 5110–22. https://doi.org/10.1021/la304456n.). These nanoparticles have raised significant interest for their astonishing mechanical, optical, and barrier properties, as well as their high tunability through functionalization (Ly, B., W. Thielemans, A. Dufresne, D. Chaussy, and M. N. Belgacem. 2008. “Surface Functionalization of Cellulose Fibres and Their Incorporation in Renewable Polymeric Matrices.” Composites Science and Technology 68, nos. 15–16: 3193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2008.07.018.; Dufresne, Alain. 2017. Nanocellulose: From Nature to High Performance Tailored Materials. 2nd ed. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110480412.). More specifically, the shared cellulosic nature of the nanocellulose-based treatments and the treated material, together with the small particle size, ensures a high compatibility between nanocellulose and canvas substrates to be treated. In that respect, they can offer an alternative to current adhesives used in conservation (e.g., animal glue, wax resin) and the risks associated with their poor reversibility and degradation (Bomford, David, and Sarah Staniforth. 1981. “Wax–Resin Lining and Colour Change: An Evaluation.” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 5: 58–65.; McGlinchey, Christopher, Rebecca Ploeger, Annalisa Colombo, Roberto Simonutti, Michael Palmer, Oscar Chiantore, Robert Proctor, Bertrand Lavédrine, and E. René de la Rie. 2011. “Lining and Consolidating Adhesives: Some New Developments and Areas of Future Research.” In Adhesives and Consolidants for Conservation: Research and Applications; Proceedings of Symposium 2011, October 17–21, 265–84. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute.; Feller, Robert L., Mary Curran, and Catherine Bailie. 1981. “Photochemical Studies of Methacrylate Coatings for the Conservation of Museum Objects.” In Photodegradation and Photostabilization of Coatings, 183–96. ACS Symposium Series, vol. 151. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-1981-0151.ch013.). However, the mode of interaction between these new biopolymers and existing canvas cellulose fibers needs to be understood in far greater detail in order to advise both materials scientists and conservators about the merits and limitations of these new materials.

In the framework of the Nanorestart project,1 a range of nanoproducts were developed as consolidants (Bridarolli, Alexandra. 2019. “Multiscale Approach in the Assessment of Nanocellulose-Based Materials as Consolidants for Painting Canvases.” PhD thesis, University College London.; Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.; Palladino, Nicoletta, Marei Hacke, Giovanna Poggi, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Krzysztof Kolman, Qingmeng Xu, Michael Persson, Rodorico Giorgi, Krister Holmberg, Piero Baglioni, and Romain Bordes. 2020. “Nanomaterials for Combined Stabilisation and Deacidification of Cellulosic Materials—The Case of Iron-Tannate Dyed Cotton.” Nanomaterials 10, no. 5: 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10050900.; Xu, Q., G. Poggi, C. Resta, M. Baglioni, and P. Baglioni. 2020. “Grafted Nanocellulose and Alkaline Nanoparticles for the Strengthening and Deacidification of Cellulosic Artworks.” Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 576: 147–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2020.05.018.). They included, first, nanocellulose-based products with the aqueous dispersions of cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs), carboxymethylated CNFs (CCNFs), and cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), as well as composite materials made of mixtures of CNF or CNC and cellulose derivative (e.g., methyl cellulose) in polar or apolar solvents. They also encompassed multilayered nanoparticles with a central inorganic core and two organic layers, the outer one being of cellulosic nature.

The mechanical and physicochemical properties of the nanocellulose-based consolidants for canvas were assessed and compared to traditional consolidants used in conservation such as natural (animal glue) and synthetic polymers (Paraloid B‑72, Plexisol P 550, Beva 371, Aquazol 200) (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Aurélia Chevalier, Marianne Odlyha, and Laurent Bozec. 2020. “Systematic Mechanical Assessment of Consolidants for Canvas Reinforcement under Controlled Environment.” Heritage Science 8, art. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00396-x.; Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.). Preliminary tests were performed on a model aged cotton canvas. The morphological, chemical, and mechanical properties of the canvas samples before and after treatment were evaluated by field emission gun scanning electron microscopy (FEG-SEM), tensile tests, and dynamic mechanical analysis under controlled RH cycling (DMA-RH) (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Aurélia Chevalier, Marianne Odlyha, and Laurent Bozec. 2020. “Systematic Mechanical Assessment of Consolidants for Canvas Reinforcement under Controlled Environment.” Heritage Science 8, art. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00396-x.; Bridarolli, Alexandra. 2019. “Multiscale Approach in the Assessment of Nanocellulose-Based Materials as Consolidants for Painting Canvases.” PhD thesis, University College London.; Bridarolli, Alexandra, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Marianne Odlyha, Marta Oriola, Romain Bordes, Krister Holmberg, Manfred Anders, Aurelia Chevalier, and Laurent Bozec. 2018b. “Nanocellulose-based Materials for the Reinforcement of Modern Canvas-supported Paintings.” Studies in Conservation 63, sup. 1: 332–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2018.1475884.). Additionally, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to nondestructively quantify the adhesion between the different compounds of this multilayered structure (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Marianne Odlyha, Marta Oriola, Romain Bordes, Krister Holmberg, Manfred Anders, Aurelia Chevalier, and Laurent Bozec. 2018b. “Nanocellulose-based Materials for the Reinforcement of Modern Canvas-supported Paintings.” Studies in Conservation 63, sup. 1: 332–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2018.1475884.).

Finally, assessment of the newly developed consolidants, including the nanocellulose and multilayered particles, was performed on sacrificial historical paintings to validate the results obtained on the cotton canvas mock-ups. The consolidation achieved was also quantified by DMA-RH. Variations in the visual and aesthetic appearance of the treated paintings and the handling properties of the different nanoproducts were evaluated, as they were also deemed essential by conservators.

Material and Methods

Canvases

Two plain-weave canvases were selected (modern cotton and historical linen). Cotton canvas, 341 g/2 density and 9 and 11 threads/cm in the warp and weft directions, respectively, was purchased from Barna Art (Barcelona, Spain) and artificially aged before testing, reaching a degree of polymerization of 450. This was to mimic the state of degradation of a painting canvas for which consolidation treatment would be required (Oriola, Marta, Gema Campo, Matija Strlič, Linda Csefalvayova, Marianne Odlyha, and Alenka Možir. 2011. “Non-Destructive Condition Assessment of Painting Canvases Using Near Infrared Spectroscopy.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 19–23 September 2011: Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland and Catherine Antomarchi, 408. Almada, Portugal: Artes Gráficas Critério; Paris: ICOM.). The aging protocol involved immersing the canvas in concentrated hydrochloric acid and hydrogen peroxide for three days, as reported elsewhere (Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.).

Linen canvas (ca. nineteenth century), previously used as a lining canvas, with dense weaving (20 and 23 threads/cm in warp and weft, respectively) and density of ~310 g/2 was also tested. The canvas was dusty and impregnated with glue (probably proteinaceous), and was therefore washed in hot water (50°C–60°C) prior to the experiment. Excess glue was scraped off the surface with a scalpel, and the canvas was left to dry under no tensioning. The threads of this canvas were thinner than the threads of the new cotton canvas and of irregular diameter.

Treatments

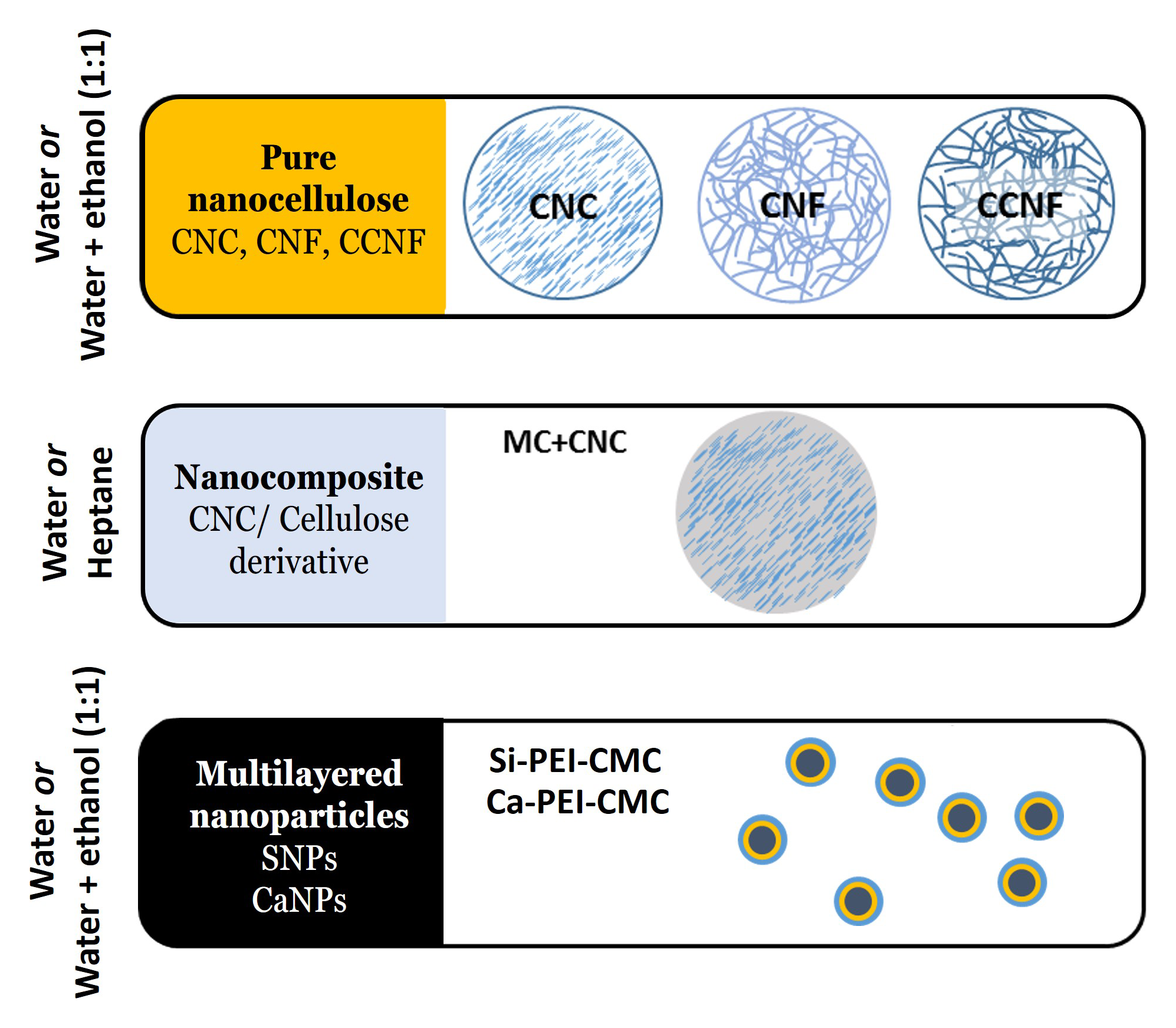

Three treatments were used: pure nanocellulose, nanocomposite, and multilayered nanoparticle (NP) consolidants, as presented in figure 27.1. Details of the treatments can be found in the Technical Information appendix.

Pure nanocellulose treatment (solution 1)

The consolidating materials consist of cellulose nanoparticles dispersed in water or a 50:50 water-ethanol solution. These can be highly crystalline, as for CNC, or less crystalline, as for CNF and CCNF. Originally extracted from wood, the particles’ size and surface properties depend on the extraction methods used and chemical functionalization. CNFs and CCNFs (chemically modified CNF) are long cellulose fibrils. In contrast, CNCs, obtained after the dissolution of the amorphous phase of cellulose through acid hydrolysis, are typically smaller NPs in the shape of a rice grain. CNCs are 7.5 ± 2.8 nm in diameter and ~0.5 µm in length; the CNFs are 7.0 ± 2.8 nm in diameter and longer than CNCs, with lengths of several micrometers. CCNF corresponds to CNF particles chemically modified to obtain CNF with carboxymethyl groups along the cellulosic chain. The particles are usually similar in size to CNF with fibrils of several micrometers in length but are also much thinner (2.4 ± 0.9 nm diameter) (Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.). Combined with a higher surface charge density, CCNFs yield thicker suspensions.

Nanocomposite treatment (solution 2)

The second solution consists of a methyl hydroxyethyl cellulose–CNC nanocomposite (MC+CNC) in water (w) or in heptane (h) following silylation (Böhme, Nadine, Manfred Anders, Tobias Reichelt, Katharina Schuhmann, Alexandra Bridarolli, and Aurelia Chevalier. 2020. “New Treatments for Canvas Consolidation and Conservation.” Heritage Science 8, art. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-0362-y.). Methyl hydroxyethyl cellulose is an adhesive commonly used in paper conservation and has proven to be stable over time (Feller, Robert L., and Myron Wilt. 1990. Evaluation of Cellulose Ethers for Conservation. Research in Conservation, vol. 3. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/cellulose_ethers.html.). It is a very hygroscopic material with excellent adhesion properties but reduced stiffness. As a result, its use as a consolidant is inadequate, and it requires the addition of a nanocellulosic filler. A small amount of nanofiller (from 5% to 15% in weight) added to materials in diverse areas from construction (concrete) to food science has been shown to improve their mechanical properties and reduce hygroscopic behavior (Azeredo, Henriette M. C., Luiz Henrique C. Mattoso, Roberto J. Avena-Bustillos, Gino Ceotto Filho, Maximiliano L. Munford, Delilah Wood, and Tara H. McHugh. 2010. “Nanocellulose Reinforced Chitosan Composite Films as Affected by Nanofiller Loading and Plasticizer Content.” Journal of Food Science 75, no. 1: N1–N7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01386.x.; Kaboorani, Alireza, Nicolas Auclair, Bernard Riedl, and Véronic Landry. 2016. “Physical and Morphological Properties of UV-Cured Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC) Based Nanocomposite Coatings for Wood Furniture.” Progress in Organic Coatings 93: 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2015.12.009.; Svagan, Anna J., Mikael S. Hedenqvist, and Lars Berglund. 2009. “Reduced Water Vapour Sorption in Cellulose Nanocomposites with Starch Matrix.” Composites Science and Technology 69, no. 3–4: 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2008.11.016.).

Multilayered nanoparticle treatment (solution 3)

The last solution proposed for canvas consolidation consists of polyelectrolyte-treated silica nanoparticles (SNPs) and CaCO3 NPs (CaNPs). Silica nanoparticles have already proven to be good candidates for textile and paper reinforcement (Gärdlund, Linda, Lars Wågberg, and Renate Gernandt. 2003. “Polyelectrolyte Complexes for Surface Modification of Wood Fibres: II. Influence of Complexes on Wet and Dry Strength of Paper.” Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 218, nos. 1–3: 137–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-7757(02)00588-5.; Tan, V. B. C., T. E. Tay, and W. K. Teo. 2005. “Strengthening Fabric Armour with Silica Colloidal Suspensions.” International Journal of Solids and Structures 42, nos. 5–6: 1561–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2004.08.013.) due to their small particle size and the possibility to chemically modify their surfaces to tune their affinity for cellulose fibers, while alkaline nanoparticles have been widely used for the deacidification of textiles and paper (Giorgi, Rodorico, Luigi Dei, Massimo Ceccato, Claudius Schettino, and Piero Baglioni. 2002. “Nanotechnologies for Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Paper and Canvas Deacidification.” Langmuir 18, no. 21: 8198–203. https://doi.org/10.1021/la025964d.; Baglioni, Piero, David Chelazzi, Rodorico Giorgi, and Giovanna Poggi. 2013. “Colloid and Materials Science for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Cleaning, Consolidation, and Deacidification.” Langmuir 29, no. 17: 5110–22. https://doi.org/10.1021/la304456n.). The mixture of CaNPs and SNPs was designed to address mechanical reinforcement and deacidification with a single-step treatment. Both types of nanoparticles are functionalized first with a cationic polyelectrolyte (PEI) and then, as the outer layer, by the anionic sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). The detailed preparation procedure is reported elsewhere (Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2017. “Preparation of Silica/Polyelectrolyte Complexes for Textile Strengthening Applied to Painting Canvas Restoration.” Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 532, no. 5: 420–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.04.051., Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 1, no. 5: 2036–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00262.; Palladino, Nicoletta, Marei Hacke, Giovanna Poggi, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Krzysztof Kolman, Qingmeng Xu, Michael Persson, Rodorico Giorgi, Krister Holmberg, Piero Baglioni, and Romain Bordes. 2020. “Nanomaterials for Combined Stabilisation and Deacidification of Cellulosic Materials—The Case of Iron-Tannate Dyed Cotton.” Nanomaterials 10, no. 5: 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10050900.).

Solutions 1 and 2 were applied to degraded cotton canvases by spraying and brushing and solution 3 by spraying only. The amounts applied resulted in weight uptakes of the canvases between 1.8% and 22.1% (table 27.1).

| Solution | Sample preparation | Sample | Concentration in solution (% w/w) | Weight uptake (%) | Applications (no.) | Tensile test conditions | Young’s modulus (MPa)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spray | Untreated | — | — | — |

|

2 |

| CNF | 1 | 3 | 24 | ||||

| CCNF | 0.25 | 3 | 8 | ||||

| CNC | 3 | 3 | 36 | ||||

| Brush | Untreated | — | — | 2 | |||

| CNF | 1 | 4 | 23 | ||||

| CCNF | 1 | 4 | 24 | ||||

| 2 | Brush | MC + CNC (water) | 1.98 | 3 | 16 | ||

| MC + CNC (heptane) | 1.98 | Unknown | 7 | ||||

| 3 | Spray | Untreated | — | — | — |

|

26 |

| SNP | 4.5 | 8.6 | 2 | 55 |

Sources: Solution 1—spray preparation: Nechyporchuk et al. 2018; brush preparation: Bridarolli et al. 2020. Solution 2—preparation: Bridarolli 2019. Solution 3—preparation and data: Kolman et al. 2018.

*The stiffness (Young’s modulus) reported for solutions 1 and 2 samples was measured in the region of interest (0%–2% elongation). The data shown for solution 3 were taken from Kolman et al. 2018 and Young’s moduli calculated from the beginning of the curves (0%-4% elongation).

Table: Alexandra Bridarolli

FEG-SEM

The structural analysis of the treated samples was carried out using a Philips XL30 field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) detector (Oxford Instruments [United Kingdom]). The system was operated at 5 kV accelerating voltage. Samples (3 × 5 mm) were mounted on aluminum stubs (Agar Scientific, Essex, U.K.) and sputtered with a gold-palladium alloy (Polaron E5000 sputter coater) for one and a half minutes.

Tensile testing: Quantification of the reinforcement

Samples of degraded cotton canvas were measured by tensile testing at 20% RH (25°C) in the warp direction to investigate the impact of the treatments on the less stiff direction of the canvas. They were typically 0.7 thick × 7 × 15 mm and cut so that the width contained 10 warp threads. The measurements were performed using dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) (Tritec 2000B, Lacerta Technology, U.K.) with a load applied at 0.4 N/min. up to 6 N.

DMA-RH cycling: Assessment of the hygroscopic behavior of untreated and treated canvases through measurements of their mechanical response to RH variations

DMA-RH cycling was performed under programmed RH and fixed temperature (25°C) conditions to assess the mechanical response of the canvases to fluctuations in RH. Canvases made of natural or synthetic fibers are viscoelastic materials, meaning that their mechanical response to external stress depends on the rate of stress applied in tensile tests or frequency. It also means that they can exhibit both elastic and viscous behaviors. DMA was introduced into the evaluation of paintings conservation to measure both the elastic (storage) modulus, E’, and viscous (loss) modulus, E’', components in the mechanical response of samples from paintings. Its first use was to measure the glass transition temperature of paint films (Hedley, G., M. Odlyha, A. Burnstock, J. Tillinghast, and C. Husband. 1991. “A Study of the Mechanical and Surface Properties of Oil Paint Films Treated with Organic Solvents and Water.” Journal of Thermal Analysis 37, no. 9: 2067–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01905579.), and was subsequently used in studies of painting canvases (Odlyha, M., T. Y. A. Chan, and O. Pages. 1995. “Evaluation of Relative Humidity Effects on Fabric-Supported Paintings by Dynamic Mechanical and Dielectric Analysis.” Thermochimica Acta 263, no. 1: 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-6031(94)02387-4.; Foster, G., M. Odlyha, and Stephen Hackney. 1997. “Evaluation of the Effects of Environmental Conditions and Preventive Conservation Treatment on Painting Canvases.” Thermochimica Acta 294, no. 1: 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6031(96)03147-4.).

For this study, a new protocol was developed (involving programmed RH cycling between low and high RH levels) based on studies of the viscoelastic response to RH variations of electrospun nanocellulose composite nanofibers by Peresin et al. (Peresin, Maria S., Youssef Habibi, Arja-Helena Vesterinen, Orlando J Rojas, Joel J. Pawlak, and Jukka V Seppa. 2010. “Effect of Moisture on Electrospun Nanofiber Composites of Poly(vinyl alcohol) and Cellulose Nanocrystals,” Biomacromolecules 11, no. 9: 2471–77. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm1006689.). This protocol was recently applied to evaluate the effects of environmental conditions and conservation treatments on painting canvases (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Marianne Odlyha, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Krister Holmberg, Cristina Ruiz-Recasens, Romain Bordes, and Laurent Bozec. 2018a. “Evaluation of the Adhesion and Performance of Natural Consolidants for Cotton Canvas Conservation.” ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 10, no. 39: 33652–61. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b10727., Bridarolli, Alexandra, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Aurélia Chevalier, Marianne Odlyha, and Laurent Bozec. 2020. “Systematic Mechanical Assessment of Consolidants for Canvas Reinforcement under Controlled Environment.” Heritage Science 8, art. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00396-x.). The RH range for the tests (from 20% to 80% RH) was selected so that the current study could be correlated with previous studies on the response of painting materials to moisture, which often take values between 10% and 90% RH (Andersen, Cecil Krarup. 2013. “Lined Canvas Paintings: Mechanical Properties and Structural Response to Fluctuating Relative Humidity, Exemplified by the Collection of Danish Golden Age Paintings at Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK).” PhD diss., School of Conservation, KADK Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.; Hedley, Gerry. 1988. “Relative Humidity and the Stress/Strain Response of Canvas Paintings: Uniaxial Measurements of Naturally Aged Samples.” Studies in Conservation 33, no. 3: 133–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/1506206.; Mecklenburg, Marion F. 2007a. “Determining the Acceptable Ranges of Relative Humidity and Temperature in Museums and Galleries, Part 1: Structural Response to Relative Humidity.” Report, Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Washington, DC. https://repository.si.edu/handle/10088/7056.; Wood, Joseph D., Cécilia Gauvin, Christina R. T. Young, Ambrose C. Taylor, Daniel S. Balint, and Maria N. Charalambides. 2018. “Cracking in Paintings Due to Relative Humidity Cycles.” Procedia Structural Integrity 13: 379–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostr.2018.12.063.).

Canvas samples, typically 7 × 15 mm, were tested in tension at 1 Hz in the warp direction. A preload (1 N) was applied to avoid buckling of the samples.

DMA at fixed RH: Assessment of the mechanical consolidation of historical lining canvas

A protocol was developed specifically for the historical linen canvas to enable testing the sample nondestructively before and after application of the treatments. DMA testing was used instead of tensile testing (for the latter, plastic—hence irreversible—deformation is usually applied). This was essential due to the irregular structure of the canvas and inhomogeneous distribution of remains of glue. Samples (15 × 7 mm)—cut in the same direction and impossible to identify as warp or weft—were clamped before the treatment application on a weighing boat cut into a frame to avoid shrinkage or deformation. The same amount of treatment, resulting in a 3% added weight, was applied to each clamped canvas sample and spread using a spatula. The storage modulus (E’) of the linen canvas samples was measured three times before and after the application of the treatments (left to dry for two days) at constant RH and temperature (30% RH, 25°C), chosen as typical room conditions. Each sample was preconditioned overnight at 20% RH prior to the tests.

Results

Appearance, Mode of Deposition, and Role in Consolidation Achieved

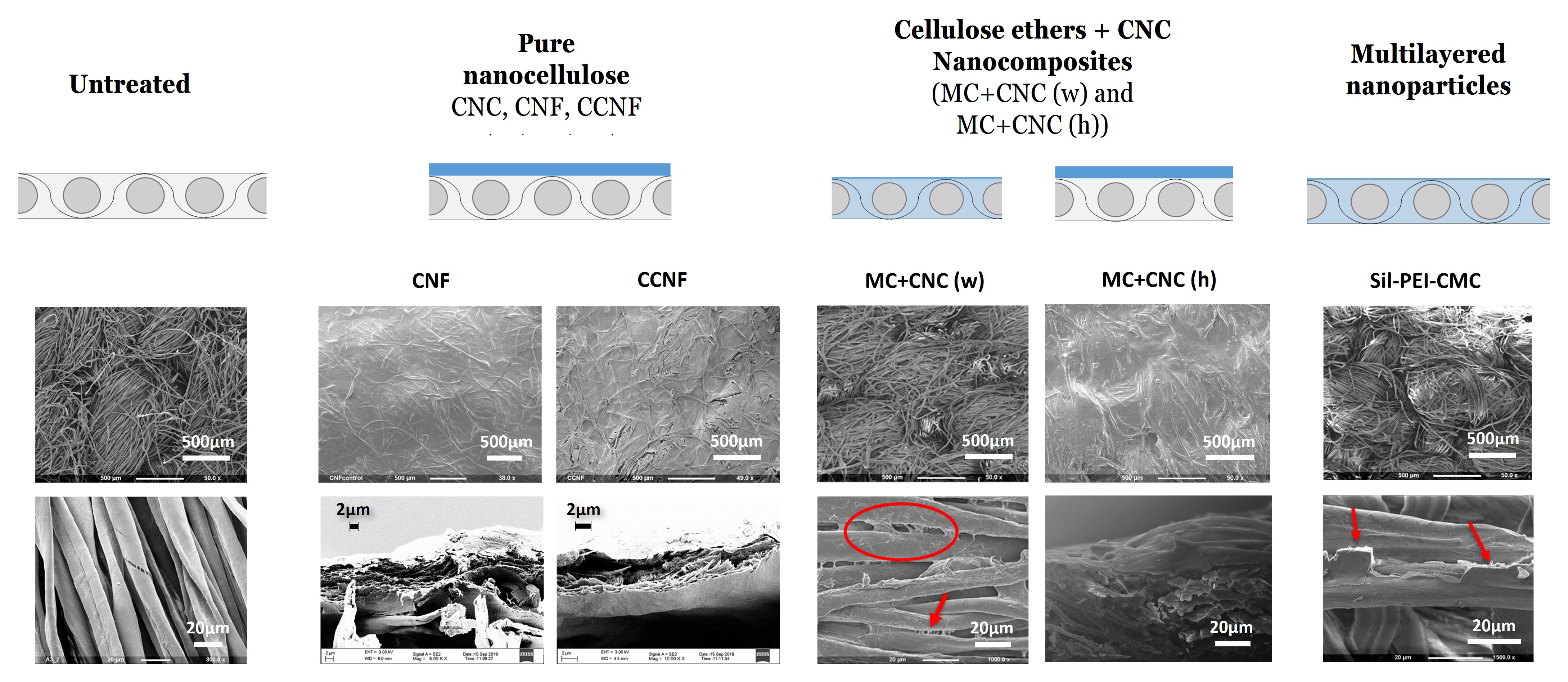

Pure nanocellulose treatments (solution 1) form a thin layer of a few microns on top of the canvas (fig. 27.2). Previous studies also reported this observation, adding that the CNC coating was particularly dense compared to the two other treatments (Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.). They also observed the formation of interfibrillar bridges between fibers of the treated surface (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Marianne Odlyha, Marta Oriola, Romain Bordes, Krister Holmberg, Manfred Anders, Aurelia Chevalier, and Laurent Bozec. 2018b. “Nanocellulose-based Materials for the Reinforcement of Modern Canvas-supported Paintings.” Studies in Conservation 63, sup. 1: 332–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2018.1475884.). The roughness of the canvas also seems visually reduced. For this specific treatment, the results in terms of deposition/penetration showed were independent of the mode of application (spray or brush), but this was not the case for results with solutions 2 and 3. Greater penetration of the treatment was achieved for the aqueous nanocomposite treatment MC+CNC (w) when brushed on (see fig. 27.2). In a separate study, a fluorescent dye (rhodamine B) was used mixed with the treatments (Bridarolli, Alexandra. 2019. “Multiscale Approach in the Assessment of Nanocellulose-Based Materials as Consolidants for Painting Canvases.” PhD thesis, University College London.). This approach enabled us to follow the penetration of the treatment in the canvas and observe that an almost complete impregnation of the canvas could be achieved. Spraying the treatment, instead of brushing it on, limited the penetration to the very first micrometers of the treated surface, resulting in a surface coating similar to that obtained with the pure nanocellulose consolidants. The hydrophobic MC+CNC (h) also showed limited penetration, probably caused by the high viscosity of the treatment and its fast drying time.

Multilayered NPs sprayed onto degraded cotton canvases tend to be homogeneously distributed across the surface of the canvas’s fibers and to form homogeneous monolayers (Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 1, no. 5: 2036–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00262.). Interfibrillar bridges made of dense agglomerate of NPs were also observed by SEM (red arrows in fig. 27.2, solution 3) and could participate in the consolidation by locking the fibrous structure. Kolman et al. also observed the high penetration achieved for the NPs using micro-X-ray fluorescence but stressed the role of viscosity as a limiting factor (Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 1, no. 5: 2036–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00262.). For concentrations above 4.5% w/w in water, the NPs remained on the canvas surface.

Consolidation

The increase in stiffness was used to rank the effectiveness of the consolidation provided and was calculated in the range of 1%–2% elongation, which is what is typically used to restretch canvases (Mecklenburg, Marion F. 1982. “Some Aspects of the Mechanical Behavior of Fabric Supported Paintings: Report to the Smithsonian Institution.” Unpublished report, Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Washington, DC. Reprinted in Dawn V. Rogala, Paula T. DePriest, A. Elena Charola, and Robert J. Koestler, eds. The Mechanics of Art Materials and Its Future in Heritage Science, 107–29. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.11342126.). This decision was driven by the understanding that in any painting in need of consolidation due to a very weak canvas, both the paint and ground layers are no longer supported by it, and it is the ground layer that acts as a supporting medium. Effective consolidation of the canvas should, therefore, ensure that the stiffness of the canvas matches that of the ground and paint layers it supports. A similar response to moisture as that of the original canvas or ground and paint layer should also be favored, as any deviation in this response may result in the creation of significant internal stresses, which ultimately lead to mechanical failure. The Young’s moduli reported in table 27.1, and measured from the tensile curves, show that higher stiffness (hence consolidation) was attained with the pure nanocellulose treatments than with the nanocomposites. The reinforcement provided was not influenced by the method of application (brushing or spraying).

Kolman et al. also reported higher consolidation achieved on degraded cotton canvas for the multilayered NPs than for the CNF treatment (Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 1, no. 5: 2036–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00262.). However, these results cannot be directly compared to those shown for solutions 1 and 2, as the experimental conditions and direction of testing used differed between the tests (see table 27.1). The stiffness achieved by all the treatments proved to be adequate, as considered by the conservators. Nechyporchuk et al. reported similar values of stiffness for CNF-, CCNF-, and CNC-treated degraded cotton canvases compared to sized and primed degraded cotton canvases measured in the weft direction (Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.).

Penetration, Cohesion, and Adhesion

The performance of the consolidants relies mainly on their penetration, adhesion, and cohesion, which could, therefore, be tuned to improve the reinforcement provided. The penetration of the treatments can affect the reversibility of the treatments, but it also plays a role in the consolidation achieved, its efficiency, and its stability. As reported in table 27.1, a lower consolidation is achieved by the nanocomposite treatments compared to the pure nanocellulosic treatments for the same weight added. This could be explained by the fact that because of the higher penetration of the MC+CNC (w) treatment, a greater amount of treatment is required to fill up the canvas volume and reach a reinforcement equivalent to the one provided by CNF, CCNF, and CNC. Regarding the pure nanocellulose treatments, which behave as surface coatings, the consolidation is provided by this additional stiff layer.

The role of adhesion was demonstrated in a study on CNF-reinforced cotton canvases (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Marianne Odlyha, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Krister Holmberg, Cristina Ruiz-Recasens, Romain Bordes, and Laurent Bozec. 2018a. “Evaluation of the Adhesion and Performance of Natural Consolidants for Cotton Canvas Conservation.” ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 10, no. 39: 33652–61. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b10727.). Using atomic force microscopy (AFM) to quantify the adhesion forces between canvas and treatments, it was demonstrated that the addition of a cationic polymer between the canvas and the CNF improved adhesion and resulted in increased efficiency of the nanocellulosic consolidation. However, since the polymer was also associated with a strong yellowing of the canvas, this consolidation strategy was discarded.

The last important factor affecting the consolidation is the cohesive properties of the material. Examples are the pure nanocellulose treatments, whose efficiency could be undermined by their loss of cohesion due to brittleness. As highlighted in past studies (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Marianne Odlyha, Marta Oriola, Romain Bordes, Krister Holmberg, Manfred Anders, Aurelia Chevalier, and Laurent Bozec. 2018b. “Nanocellulose-based Materials for the Reinforcement of Modern Canvas-supported Paintings.” Studies in Conservation 63, sup. 1: 332–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2018.1475884.; Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.; Bridarolli, Alexandra, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Aurélia Chevalier, Marianne Odlyha, and Laurent Bozec. 2020. “Systematic Mechanical Assessment of Consolidants for Canvas Reinforcement under Controlled Environment.” Heritage Science 8, art. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00396-x.), sudden discontinuities in the stress-strain curves result from rupture of coatings formed by the pure nanocellulose, whether sprayed or brushed on the canvases. The mechanical failure of the treatments could occur at elongations above 1.5%, which is within the 1%–2% range typically used to restretch canvases (Mecklenburg, Marion F. 1982. “Some Aspects of the Mechanical Behavior of Fabric Supported Paintings: Report to the Smithsonian Institution.” Unpublished report, Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Washington, DC. Reprinted in Dawn V. Rogala, Paula T. DePriest, A. Elena Charola, and Robert J. Koestler, eds. The Mechanics of Art Materials and Its Future in Heritage Science, 107–29. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.11342126.). These observations highlight the risks of gradually losing the reinforcement provided over time due to repetitive handling, transport, and mechanical stresses caused by significant environmental variations. However, if they are applied in large enough quantities, it is expected that the rupture of the coating might occur at greater elongation—beyond the typical 1%–2% range used in conservation.

By observing the high penetration and bulk consolidation reached by multilayered NPs in degraded canvas, Kolman et al. suggested the use of this treatment in combination with pure nanocellulosic treatments (Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 1, no. 5: 2036–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00262.). The canvases tested with this mixture showed increased consolidation, as they benefited from a multidepth consolidation both in bulk and at the surface.

DMA-RH: Hygroscopic Response from a Mechanistic Perspective

Mechanical stresses experienced by a painting are also often caused by environmental factors, such as variations in RH and temperature. Some constitutive layers of a painting are hydrophilic and highly responsive to RH, while others are less so. Cotton and linen canvases are moisture-sensitive supports. At 65% RH, linen and cotton can take up moisture to 12% and 8.5% in mass, respectively (Hill, Callum A. S., Andrew Norton, and Gary Newman. 2009. “The Water Vapor Sorption Behavior of Natural Fibers.” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 112, no. 3: 1524–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.29725.). The individual layers also present differential mechanical responses to fluctuations in RH and temperature. Mecklenburg and Hedley have shown that canvas and glue layers, being responsive to moisture, will swell or contract and respond to RH changes faster than other layers (Mecklenburg, Marion F. 1982. “Some Aspects of the Mechanical Behavior of Fabric Supported Paintings: Report to the Smithsonian Institution.” Unpublished report, Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Washington, DC. Reprinted in Dawn V. Rogala, Paula T. DePriest, A. Elena Charola, and Robert J. Koestler, eds. The Mechanics of Art Materials and Its Future in Heritage Science, 107–29. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.11342126.; Hedley, Gerry. 1988. “Relative Humidity and the Stress/Strain Response of Canvas Paintings: Uniaxial Measurements of Naturally Aged Samples.” Studies in Conservation 33, no. 3: 133–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/1506206.). The glue layer will become more brittle or more plastic at low and high RH levels, respectively. The canvas in contrast will develop greater forces above 80% RH. A more hydrophobic material, such as the paint layer, will be more sensitive to change in temperature. These differential behaviors toward RH and temperature variations observed between constitutive layers of a painting can lead to the building up of strong shear and tensile stresses, which are stresses that are coplanar and perpendicular, respectively, to the face of the material on which the load is acting. As a result, delamination or the rupture of the different layers resulting from the release of the accumulated tension can occur and spread onto and across the entire painting (Bergeaud, C., J. Hulot, and A. Roche. 1997. La dégradation des peintures sur toile. Méthode d’examen des altérations. Paris: École Nationale du Patrimoine.; Karpowicz, Adam. 1989. “In-Plane Deformations of Films of Size on Paintings in the Glass Transition Region.” Studies in Conservation 34, no. 2: 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.1989.34.2.67.).

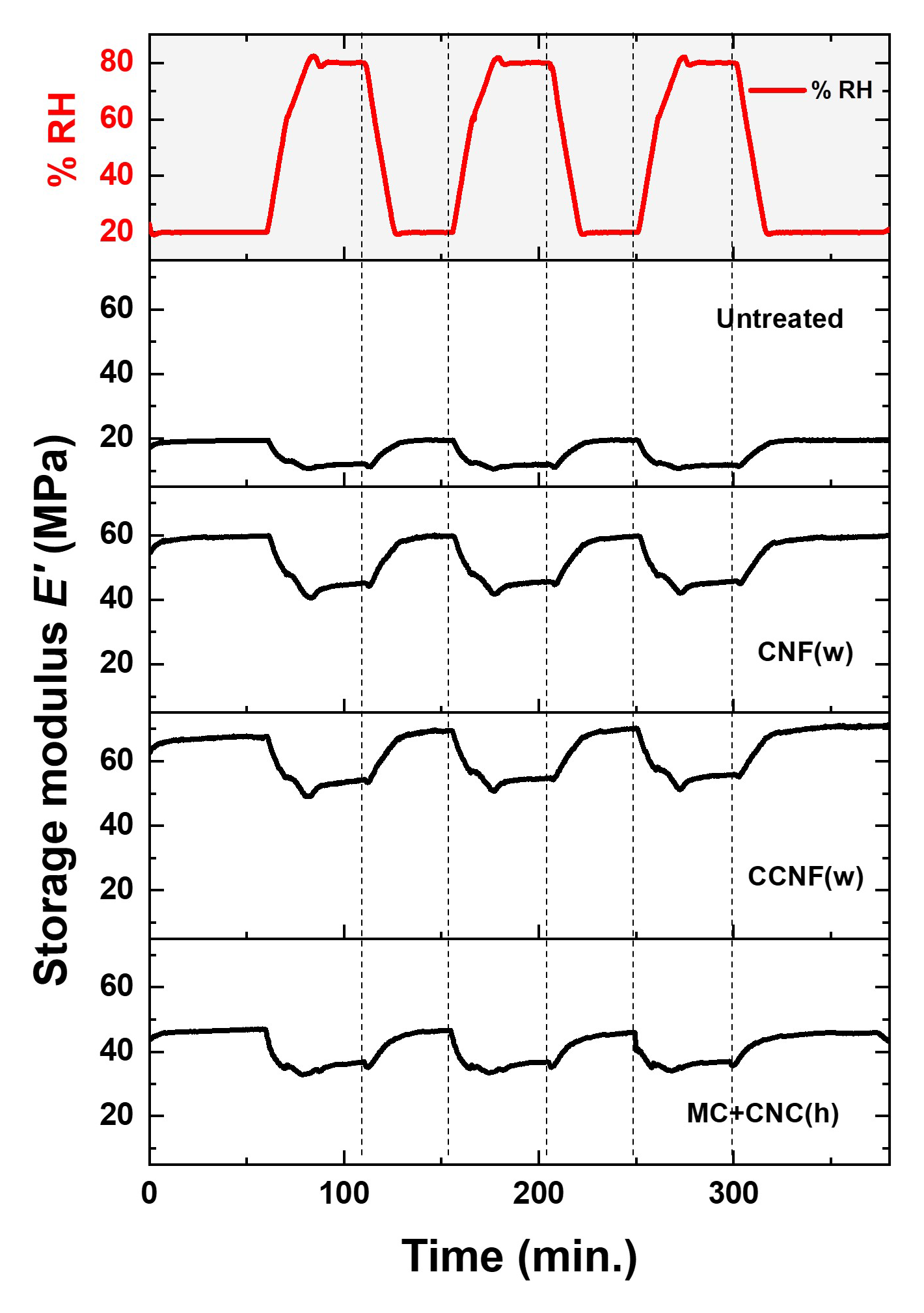

The response of samples to moisture was tested using DMA with RH cycling. Figure 27.3 demonstrates the similar mechanical behavior of the treated samples—CNF, CCNF, and MC+CNC (h)—characterized by successive decreases in storage modulus (E’) (stiffness) with RH increase (80% RH), and then increases in stiffness with RH decrease (20% RH). The magnitude of the response, however, varies between samples (table 27.2). Differences in E’ between 20% and 80% RH plateau over the three RH cycles (ΔE’20%–80% RH) show the highest value for the CNF-treated sample (ΔE’20%–80% RH =12.9±1.8 MPa) and lower values for untreated and MC+CNC (h) samples (ΔE’20%–80% RH =7.6±0.2 MPa and 8.3±0.9 MPa, respectively). Overall, these results and previous studies have shown that the change in stiffness of the treated samples remains higher than for the untreated canvas, except for CNC-treated samples tested using 20%–60% RH cycles (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Marianne Odlyha, Marta Oriola, Romain Bordes, Krister Holmberg, Manfred Anders, Aurelia Chevalier, and Laurent Bozec. 2018b. “Nanocellulose-based Materials for the Reinforcement of Modern Canvas-supported Paintings.” Studies in Conservation 63, sup. 1: 332–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2018.1475884.; Bridarolli, Alexandra. 2019. “Multiscale Approach in the Assessment of Nanocellulose-Based Materials as Consolidants for Painting Canvases.” PhD thesis, University College London.). It is yet to be understood whether the magnitude of these changes in stiffness would pose a risk to paintings.

| Solution | Sample | ΔE'20%–80%[E'20% RH– E'80% RH] |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 7.6 ± 0.2 | |

| 1 | CNF | 12.9 ± 1.8 |

| CCNF | 9.9 ± 2.1 | |

| 2 | MC+CNC (heptane) | 8.3 ± 0.9 |

Testing on Historical Canvases

Visual assessment as well as handling properties of the treatments were evaluated on different occasions in the framework of the Nanorestart project by a small group of paintings conservators, and results were recently published (Oriola-Folch, Marta, Gema Campo-Francés, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Cristina Ruiz-Recasens, and Iris Bautista-Morenilla. 2020. “Novel Nanomaterials to Stabilise the Canvas Support of Paintings Assessed from a Conservator’s Point of View.” Heritage Science 8, art. 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00367-2.; Böhme, Nadine, Manfred Anders, Tobias Reichelt, Katharina Schuhmann, Alexandra Bridarolli, and Aurelia Chevalier. 2020. “New Treatments for Canvas Consolidation and Conservation.” Heritage Science 8, art. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-0362-y.). Tests were carried out on modern linen, cotton, and jute canvases; on historical lining canvases (linen); and on nineteenth- and twentieth-century acrylic- and oil-based paintings on linen and cotton canvases. Overall, the authors reported that all the new products performed well on white cotton canvases. On darker canvases, most of the treatments showed minimal color change, especially compared to the traditional animal-glue consolidant, which darkens canvases (Oriola-Folch, Marta, Gema Campo-Francés, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Cristina Ruiz-Recasens, and Iris Bautista-Morenilla. 2020. “Novel Nanomaterials to Stabilise the Canvas Support of Paintings Assessed from a Conservator’s Point of View.” Heritage Science 8, art. 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00367-2.). The only exceptions were the heptane-based nanocomposites, which strongly whiten the canvas, especially the formulation mixed with nanoparticles of MgO. (This was part of a strategy combining consolidation with canvas deacidification.) Change in gloss was also observed only for the heptane-based nanocomposites.

Following these evaluations, further mechanical tests were carried out using one of the lining canvases found in Böhme’s study (Böhme, Nadine, Manfred Anders, Tobias Reichelt, Katharina Schuhmann, Alexandra Bridarolli, and Aurelia Chevalier. 2020. “New Treatments for Canvas Consolidation and Conservation.” Heritage Science 8, art. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-0362-y.). The protocol developed for these tests enabled assessment of the treatments on more representative canvases (historical material, naturally aged, soiled, and with traces of one or more glues), while minimizing the variability due to the inhomogeneous nature of these materials. For these final tests, the water-based and heptane-based nanocomposites tested were mixed with deacidification agents: CaCO3 and MgO, respectively. The presence of CaCO3 had been shown not to affect the reinforcement provided by MC+CNC in water (Bridarolli, Alexandra. 2019. “Multiscale Approach in the Assessment of Nanocellulose-Based Materials as Consolidants for Painting Canvases.” PhD thesis, University College London.). Canvases treated with the solvents used in the treatments were also tested in order to isolate the impact of the treatment from the solvent itself.

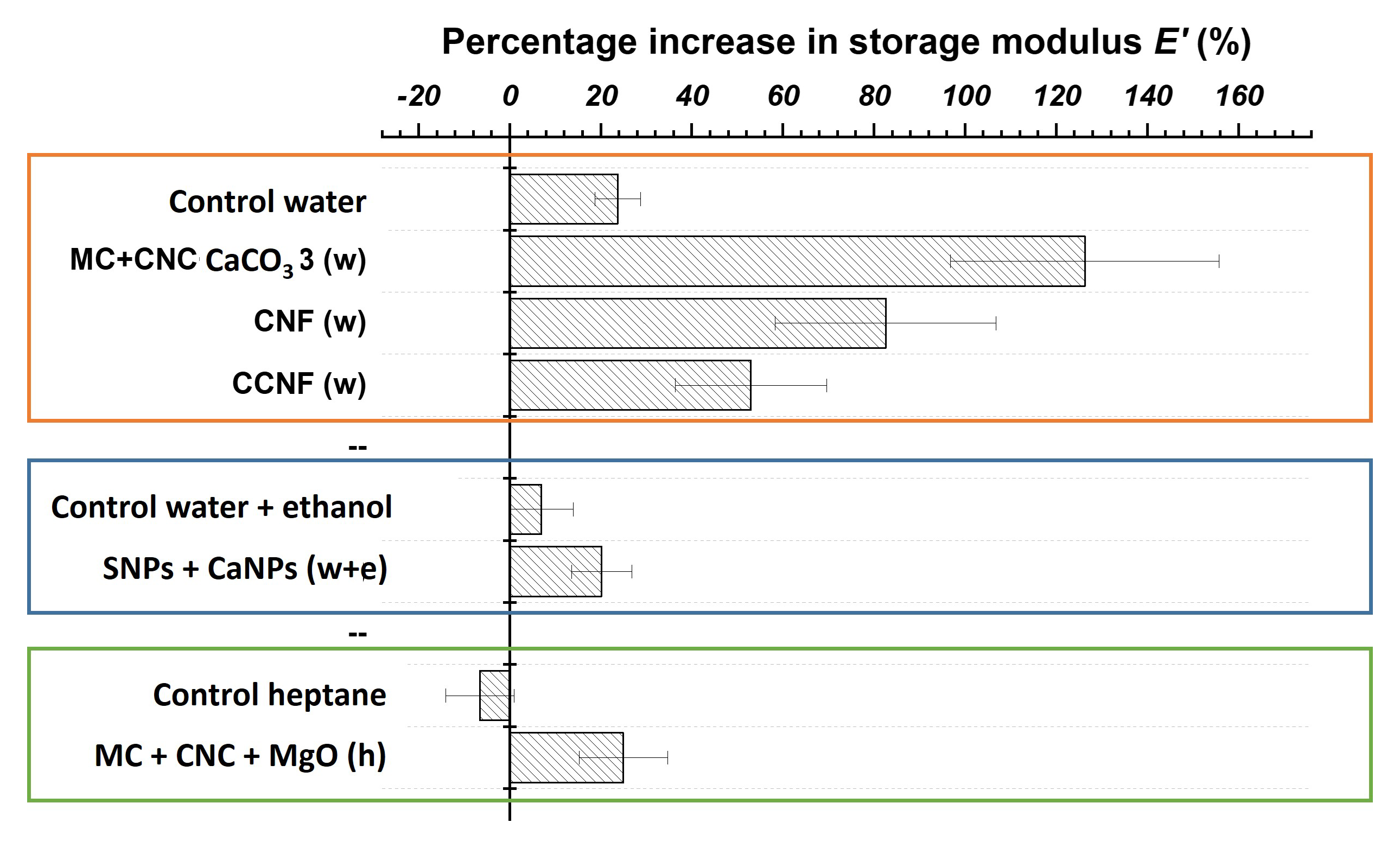

Figure 27.4 shows the calculated percentage increase in storage modulus E’ (30% RH, 25°C, 30 min. equilibration) measured for the linen canvas samples and resulting from the application of the treatments. All led to the consolidation of the historical canvases, seen in the increase in stiffness (E’). The greatest increase in E’ was reached with the MC+CNC+CaCO3 (w) treatment (increase of 126% ±30%), followed by CNF (83% ±24%) and CCNF (53% ±17%). The high level of stiffening reached using MC+CNC+CaCO3 (w) was not observed for its counterpart, the heptane-based treatment MC+CNC+MgO (h) (25 ±10%), nor was it for the multilayered NPs (20% ±17%). The limited consolidation conferred by the latter on the historical linen canvas calls for further research, as this contradicts previous tensile testing results performed on degraded modern cotton canvases (see table 27.1).

The results gathered on historical lining canvas confirm those obtained on degraded modern cotton canvases. They also show that the inherent presence of traces of glue or oil-based substances on historical canvases may inevitability lead to modifications of their mechanical properties through the application of solvent alone. The application of water alone led to a significant increase in canvas’s stiffness (~22%) in comparison to heptane, which tends to soften the canvas (see fig. 27.4). This could explain the higher consolidation reached for the MC+CNC+CaCO3 (w) treatment compared to CNF, CCNF, and CNC treatments, which was not observed when testing the degraded modern cotton canvas (see table 27.1). Due to the higher viscosity of MC+CNC+CaCO3 (w) at 2% w/w in comparison to CNF and CCNF, it is possible that the canvas might have been exposed for a longer time to the water present in the MC+CNC+CaCO3 (w) gel. This would have given more time for the remains of glue present in the lining canvas to swell and reform in a renewed sizing layer.

Summary of Effects of the Treatments on Modern Degraded Cotton and Historical Linen Samples

These studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the nanocellulose-based and multilayered nanoparticle treatments for the consolidation of degraded cotton and historical linen samples from linings. A wide range of products has been studied in both polar and apolar solvents and with different handling properties and physical behavior (viscosity, penetration, response to RH) (table 27.3), which makes them suitable for various substrates. The reinforcement provided is also greater, with less weight added, in comparison with the traditional consolidants of animal glue and Beva 371 (Bridarolli, Alexandra, Anna Nualart-Torroja, Aurélia Chevalier, Marianne Odlyha, and Laurent Bozec. 2020. “Systematic Mechanical Assessment of Consolidants for Canvas Reinforcement under Controlled Environment.” Heritage Science 8, art. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00396-x.; Nechyporchuk, Oleksandr, Krzysztof Kolman, Alexandra Bridarolli, Marianne Odlyha, Laurent Bozec, Marta Oriola, Gema Campo-Francés, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “On the Potential of Using Nanocellulose for Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” Carbohydrate Polymers 194: 161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.020.).

| Nanocellulose-only | Nanocomposite cellulose ether/CNC | Multilayered particles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

|

| Observations |

|

|

|

This research marks the first step in the introduction and evaluation of three different types of treatments using nanocellulose and multilayered nanoparticles as potential consolidants for canvas-supported paintings. Further developments and improvements of their capabilities have been shown to be possible by mixing treatments together (e.g., multiscale reinforcement mixing solutions 1 and 3), by combining deacidification and consolidation strategies (e.g., nanocomposites, multilayered NPs), or simply by changing the application method, treatment viscosity, or treatment-to-canvas adhesion. In this latter case, the adhesion could be improved through modification of the surface chemistry of the NPs used for consolidation.

Conclusions

This work has successfully evaluated the effects of the three treatments. The acceptance and validation of the products could not have been possible without the input of conservators. This fact highlights the importance of organizing future workshops using this range of nanoproducts with practicing conservators. It has also highlighted the importance of supporting the findings with quantitative assessments of the physical and mechanical properties of the consolidants. The ability to perform quantitative analysis on historical samples has been shown to optimize the evaluation protocol and to complement subjective testing procedures, and this may in turn help to speed acceptance of these new treatments. Further testing is, however, still needed to establish if the mechanical response to fluctuations in RH is within acceptable limits and, in the long term, sustainable for the safe preservation of paintings. Development of new strategies to reduce the amount of solvent applied with the treatments is also essential.

Acknowledgments

This study was cofunded by the H2020 Nanorestart European Project (grant 646063) and the United Kingdom’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) through University College London’s Centre for Doctoral Training in Science and Engineering in Arts, Heritage, and Archaeology (SEAHA).

Appendix: Technical Information

The CNF was produced from softwood pulp (~75% pine and 25% spruce, containing 85% cellulose, 15% hemicellulose, and traces of lignin, as determined by the supplier). Carboxymethylated CNF (CCNF), also in the form of an aqueous suspension, was kindly provided by Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) Bioeconomy (Sweden). The CCNF was produced from a softwood sulfite dissolving pulp (Domsjö Dissolving Plus, Domsjö Fabriker AB, Sweden) by carboxymethylation, as described by others (Wågberg, L., and M. Bjőrklund. 1993. “On the Mechanism behind Wet Strength Development in Papers Containing Wet Strength Resins.” Nordic Pulp and Paper Research Journal 8, no. 1: 53–58. https://doi.org/10.3183/npprj-1993-08-01-p053-058.), followed by mechanical fibrillation. Nanocrystalline cellulose (CNC) in powder form was purchased from CelluForce (Canada). It was produced from bleached kraft pulp by sulfuric acid hydrolysis.

The nanocomposites are made of a mixture of Tylose MH (methyl hydroxyethyl cellulose), purchased from Shin-Etsu Chemical Co. ( Japan), and cellulose nanocrystals (CelluForce NCC), obtained from CelluForce. For the heptane-based MC+CNC, hydrophobic groups were introduced by silylation (Böhme, Nadine, Manfred Anders, Tobias Reichelt, Katharina Schuhmann, Alexandra Bridarolli, and Aurelia Chevalier. 2020. “New Treatments for Canvas Consolidation and Conservation.” Heritage Science 8, art. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-0362-y.). The deacidification agents consist of calcium carbonate and magnesium oxide particles of less than 1 µm.

Other research details preparation of the SNPs (Kolman, Krzysztof, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. 2018. “Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 1, no. 5: 2036–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00262.) and CaNPs (Xu, Q., G. Poggi, C. Resta, M. Baglioni, and P. Baglioni. 2020. “Grafted Nanocellulose and Alkaline Nanoparticles for the Strengthening and Deacidification of Cellulosic Artworks.” Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 576: 147–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2020.05.018.) and their mixture (Palladino, Nicoletta, Marei Hacke, Giovanna Poggi, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Krzysztof Kolman, Qingmeng Xu, Michael Persson, Rodorico Giorgi, Krister Holmberg, Piero Baglioni, and Romain Bordes. 2020. “Nanomaterials for Combined Stabilisation and Deacidification of Cellulosic Materials—The Case of Iron-Tannate Dyed Cotton.” Nanomaterials 10, no. 5: 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10050900.).