29. Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Influence in the Consolidation of Fatimid Metalware

- Ayala Lester, Israeli Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem

Abstract

Introduction

Until recently, the availability of early Islamic metal vessels was limited to individual pieces in museums and private collections, and the scholarship was always generalized, with very limited information in regard to typology.1 Metal articles from the early centuries of Islam within the Syrian-Egyptian region are even less common, as Iran and Central Asia attracted the greater portion of attention from researchers.2

The Fatimid dynasty3 is famous for its decorative arts, which have stimulated considerable scholarly interest, and several publications have been dedicated to the subject.4 Studies of Fatimid metalware, however, were based upon a small number of vessels from a few collections.5 The situation has entirely changed over the last twenty years with the discovery in Israel of two major hoards. The first was uncovered in Caesarea in 1995 and included 136 metal articles together with glass and ceramic vessels.6 The second cache was found in 1998 in Tiberias and included 660 metal vessels along with a great deal of production waste.7

The hoard from Caesarea was discovered in the southeastern part of the city, in the area of the Temple platform, which was the city’s cultural center from Roman times up to the Crusader period. The hoard was found in a cavity near a staircase leading to the Temple platform area and included 136 metal articles, 15 vessels made of clay, and 13 glass articles. The group of metal vessels was composed of lampstands, saucepans, ladles, basins, ewers, round boxes, buckets, braziers, incense burners, and individual handles and feet used to support other vessels. A few of the vessels are splendidly decorated and very well made, while others are much simpler, testifying to a variety of clients. The hoard probably belonged to a merchant who traded in metal and other vessels originating from Palestine, Syria, and Egypt.

The cache from Tiberias was found during the salvage excavation of a dwelling area, within a private house. The vessels were hidden in three large pithoi, two of which were buried under the floor, and the third, the largest, was concealed behind a wall built specially for this purpose. The pithoi included about 660 vessels along with about 100 kilograms (220 lb.) of production waste. The vessels were very similar to those found in Caesarea, while also including parts of articles that had been serially produced, such as rims and necks of bell-shaped bottles, handles and hinges of buckets, legs to support trays, handles for bowls and cauldrons, and so forth. Working tools such as scissors, molds for sand-casting, and an anvil were also uncovered. The walls and floors of the building, comprising two rooms and a courtyard, were encrusted with flecks of base metal, resulting from the extended use of a lathe to polish and decorate the vessels. All these facts confirm that the location served as a workshop. It was most probably active between the end of the tenth century and about AD 1072, when Turkoman tribes invaded Palestine, establishing their base near Tiberias.8

This paper focuses on a few types of vessels—lampstands, saucepans, braziers, and feet and handles of vessels—in order to follow their morphological consolidation up to the Fatimid period.

Lampstands

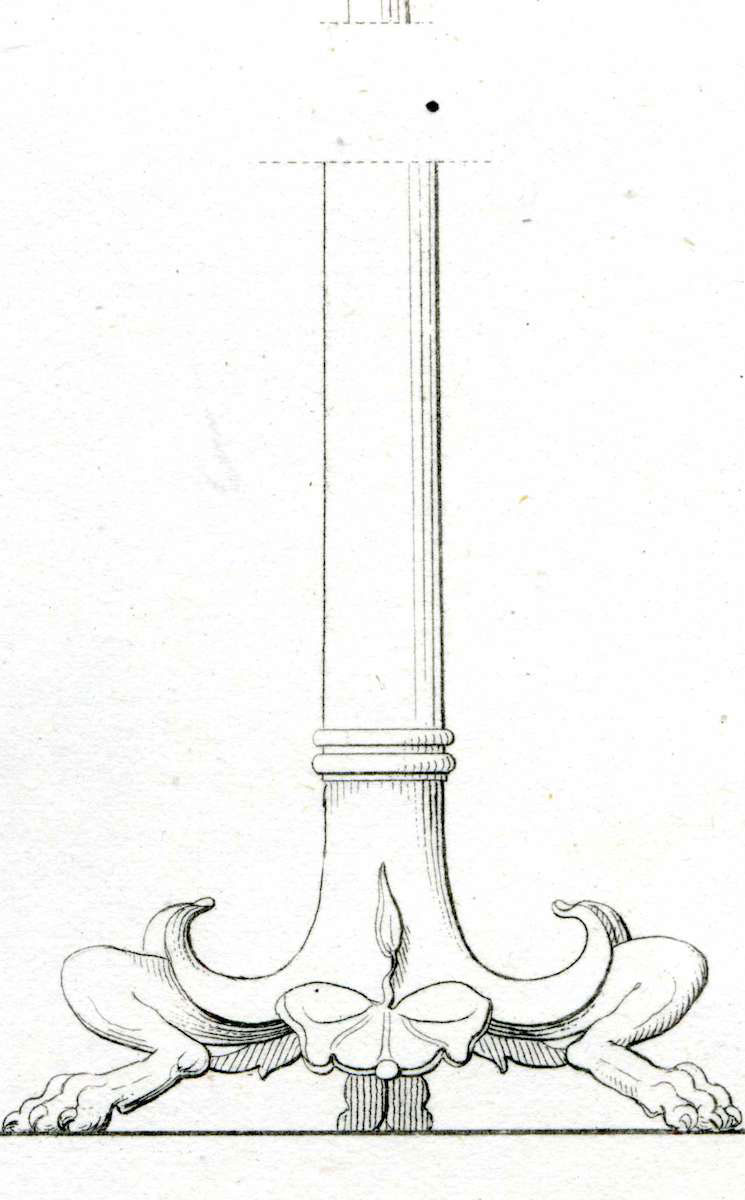

Fatimid lampstands are typically composed of three parts: a tripod base, a shaft, and a tray (fig. 29.1). The shaft is designed to fit into the central socket of the base; the bottom part of the tray was soldered to the shaft. The lampstands are characterized by a stylistic continuity between the base and the shaft; thus a base with a round body was fitted to a round shaft and a polygonal base supported a polygonal shaft.

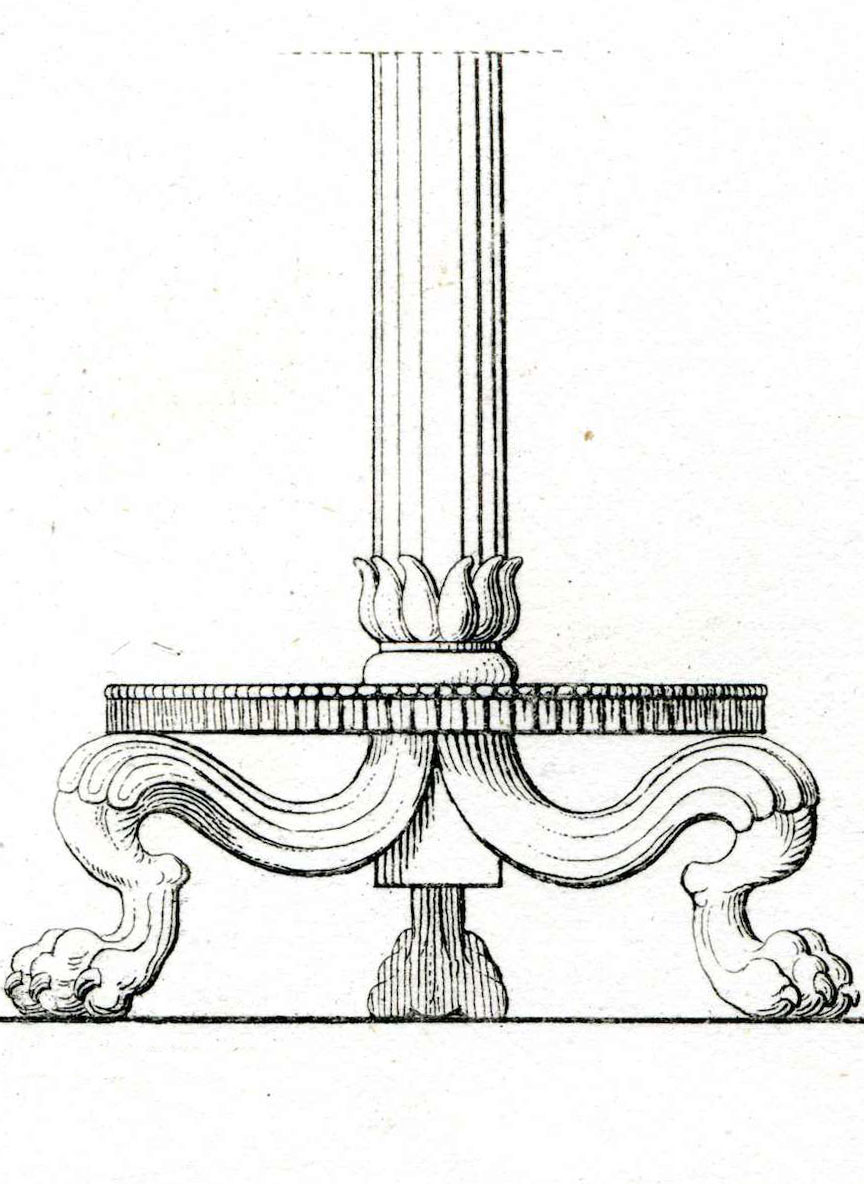

The Fatimid lampstand is the outcome of a long process of adaption, beginning in the Persian period during the late sixth to fifth century BC. The earliest example is a lampstand with three sharply bent legs with cloven hooves, and a long fluted shaft with a bowl attached on the top. Three palmettes or ivy leaves emerge between the legs.9 This tradition continues to the Early Imperial period (first–third century AD), with lampstands characterized by ivy leaf design between the legs, and a krater-shaped top (fig. 29.2a).10 In parallel, during the first century AD, we find another subtype of lampstand, with a circular plate that rests on the legs (fig. 29.2b). The decoration of the plate consists of ovolo and other moldings.11 A lampstand of the same type is dated between the second and third centuries AD; however, the plate has become convex with engraved decoration.12

Later, during the fifth and sixth centuries AD, the morphology of the lampstand changes. The round horizontal plate transforms into a tent-shaped canopy, with the protruding leaf motif combined amid the legs. The shaft has two variations. One is a solid, hexagonal form with bulges at the edges;13 the other is baluster in shape and composed of spherical balls soldered together.14 On the upper part of the lampstand, the bowl was modified into a circular tray, sometimes with a central spike on which a metal lamp was placed.15

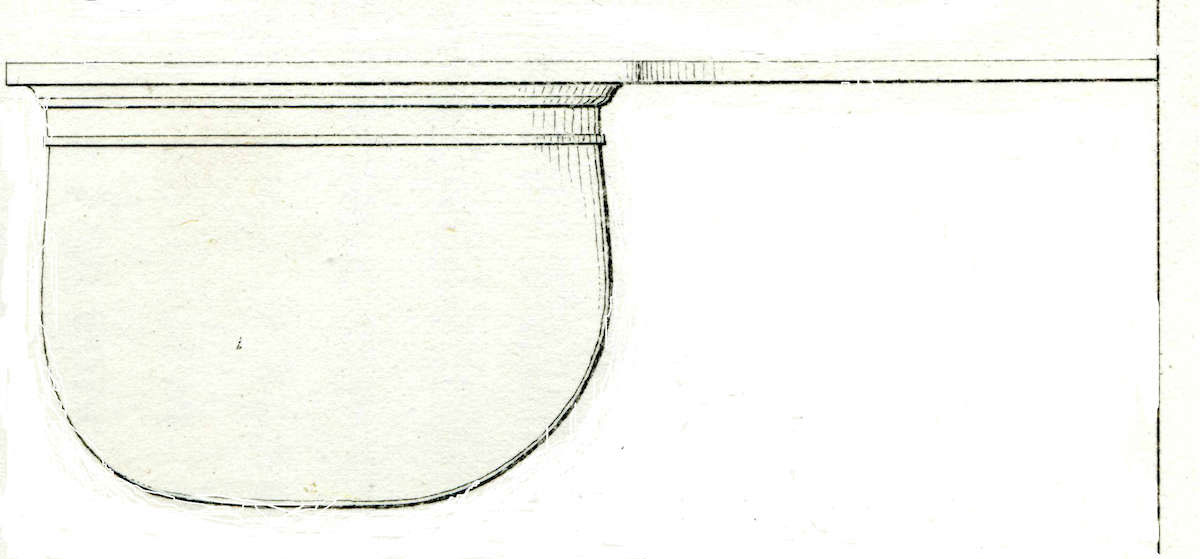

These versions of lampstands continue during the Fatimid period, but the tripod base becomes semi-spherical or polygonal in shape; the shaft is massive and heavy; and the small upper tray becomes much larger, being flat with a round rim and, in most cases, without an elevated frame. The base, with a round canopy, extends over the upper part of the feet so that the thigh disappears and the base becomes trapezoidal in shape. The shaft is composed of three parts: two balusters flanking the central main part, which is either round in section decorated on the lathe with pairs of fluted circles, or decorated with patterns of lozenges or other shapes. The stylistic identity between the base and the shaft creates sets of matching round bases with round shafts, and polygonal decorated bases and shafts. The tray, seen in profile, is a thin band: it is usually a single round flat surface soldered to the top of the shaft. It rarely bears compatible decorative ornament.

The typological considerations also include the physical perception of sizes, from the largest (diam. 31.3 cm or 12 ⅜ in.) and highest (48.2 cm or 19 in.) to a miniature lampstand with a diameter of just 6.8 centimeters (2 ¾ in.) at the base with a height of 11 centimeters (4 ⅜ in.). The miniature lampstand is in line with the stylistic characteristics of the group and has a round base with a round shaft. A prototype for the miniature circular lampstand can be seen in the collection of the British Museum and is of Egyptian origin, dated from the sixth to the seventh century AD.16

In spite of the morphological differences, the production techniques did not change over the centuries. The base and the shaft were produced using the lost-wax technique, and the tray was probably cast in a stone mold.

Saucepans/Measuring Vessels

Saucepans of various sizes were found at both Caesarea and Tiberias. They are trapezoidal in section with an everted rim and a long handle with a clover-shaped termination or a loop for suspension (fig. 29.3). They continue a tradition of saucepans from the first century AD, such as vessels found at Pompeii, dated to the first century AD, which have a convex body with a splayed rim and a long handle (fig. 29.4).17 They continue to circulate during the second and third centuries, for example in Egypt.18

These vessels have also been identified as ladles for serving food. John W. Hayes defined the vessel as a saucepan (trulla) and was not certain whether it was Roman or Islamic in origin.19 Géza Fehérvari and Elias Khamis recognized it as a dipper.20 Some of the vessels are decorated with inscriptions and tendrils. One article from Caesarea bears an inscription on its base: لصاحبه برکة (blessing to its owner). Thus, when it was not in use, it was hung on the wall with the inscription praising the owner facing outward.

These saucepans were displayed at an exhibition at the Hecht Museum in Haifa, about seventeen years ago, where Palestinian women identified the article as a measuring vessel called a Ṣaʻ (صاع.). Based upon this correlation, I measured the capacity of the vessels in order to determine if their volume is compatible with traditional Islamic measures. I included all the saucepans from Caesarea and one from Tiberias. Two vessels hold 4 liters, one 3.7 liters, and a smaller one 2.2 liters. These measurements correlate with the religious Islamic term Ṣaʻ or saa’h (صاع), which was used for a measure for grain of about 4.2 liters. The saa’h is connected with one of the commandments of Islam requiring a person to donate a measure of wheat or barley to the poor. It was issued by the Prophet Muhammad during the second year of the Hijra, as part of the ceremonies of I’d al-Fiter (Eid), the festival following the fast during the month of Ramadan.21

Furthermore, S. D. Goitein, in his comprehensive work about the Jewish communities in the Mediterranean Basin based upon the documents found at the Geniza of the Ibn-Ezra synagogue at Fustat, discusses the private home and its customs. He mentions that “a small vessel of fixed measurement and durable material such as marble was attached to the jar which enabled the housewife to control the consumption.”22 The combination of the vessel, its capacity, and the description by Goitein, together with the identification by contemporary Palestinian women, provides a firm basis to confirm that the vessel was used as a measuring cup for grain, rather than as a saucepan.

This type of vessel is known in the eastern part of the Islamic world, appearing in miniatures from the sixteenth century. A miniature from an album depicts a nomad’s camp with food cooking in a casserole and a ladle alongside.23 Another miniature from the manuscript of the Hamsa of Nizami, shows preparations for a banquet, with a servant holding a ladle and filling a dish from a cauldron.24

Braziers

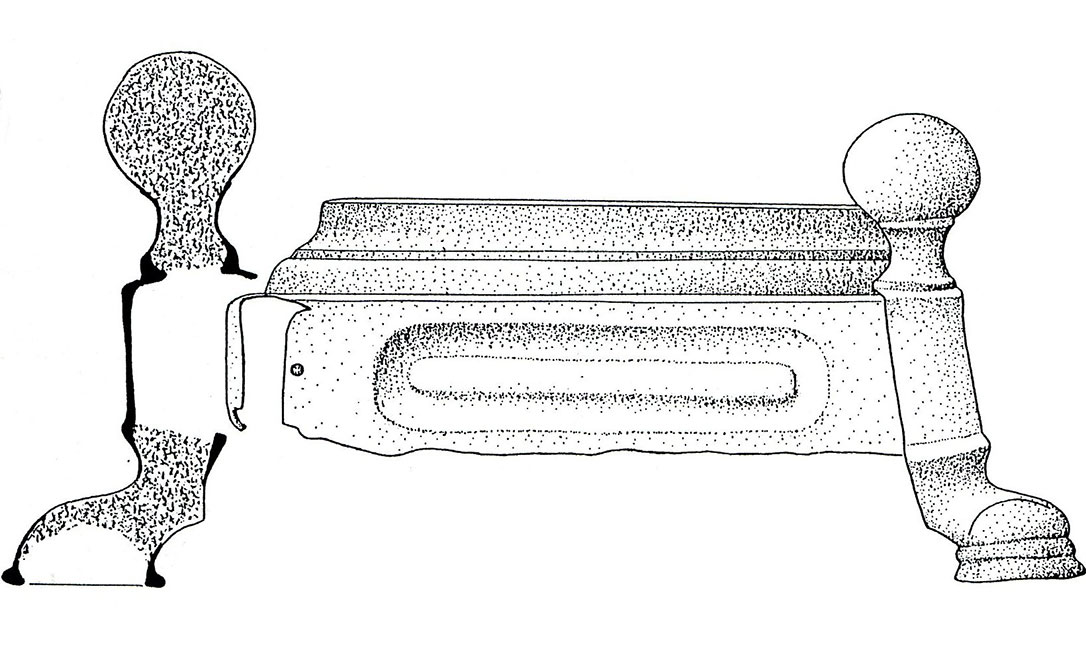

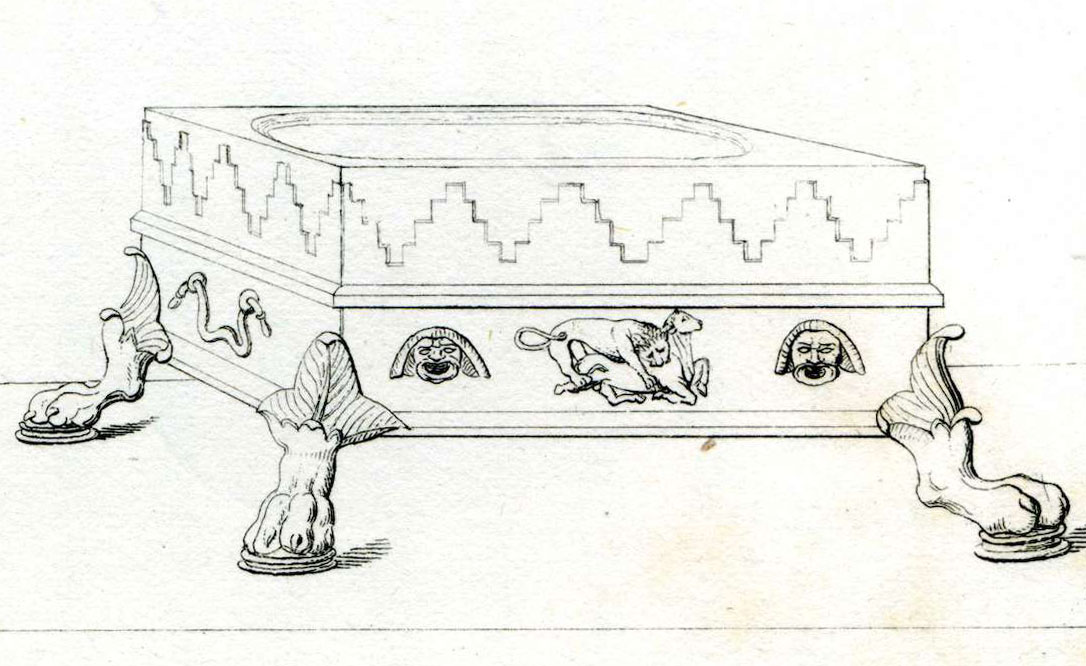

Braziers are known in two versions, square and round. Cooking in both types is based upon the heat reflected from the coals inside the vessel. The square type was used for grilling meat on skewers. It consolidated under Roman influence, as seen in a square brazier that originated in Pompeii, dated to the first century AD (fig. 29.5a). Other examples are dated to the Umayyad period, prior to AD 750, and to the Mamluk period in the second half of the thirteenth century.25 This type of brazier was used during social events such as outings, as can be seen from a miniature in a manuscript of Galen, dated to the middle of the thirteenth century, and a manuscript of the Hamsa by Nizami, from Tabriz in Persia, dated to the middle of the sixteenth century.

The second type of brazier is round with a base and an upper concave receptacle for coals. Such ceramic braziers are known from the Etruscan period (seventh–sixth century BC). They are characterized by a round container with a thickened rim, triangular in section, decorated in relief with animals walking in procession. According to Lisa Pieraccini, they were used as offerings to the dead within family tombs.26

A related version, made of clay, from the Hellenistic period was found in Palestine. The shape is based on a high cylindrical container in which the coals were kept and an upper bowl with three massive handles to support the vessel on top. It was used in private homes both as a hearth and for cooking.27 A subtype of it is known from the Fatimid period. It appears in different sizes from the very large to the very small. The largest are supported by four feet with spherical extensions that secure the container in place (fig. 29.5b). Smaller versions maintain the idea of a sunken base for the coals, but the square frame is diminished and only a bowl with a broad rim to support the pot remained. It is raised above the floor by three feet that were soldered to the base. The smallest version has an inner diameter of just 10.5 centimeters (4 in.).

It seems that these braziers continue a tradition that originated in Etruria and appeared again during the Hellenistic period. Such braziers are not known from the Roman and Byzantine periods. It may be that braziers have not been identified as such or that they were not popular during these periods; but the typological concept somehow survived and it reappears during the Fatimid period. A set including four braziers of different sizes is part of the hoard from Caesarea. The largest brazier is 39 centimeters (15 ⅜ in.) high with a diameter of 26 centimeters (10 ¼ in.). A large bag-shaped container of similar size is part of the Caesarea hoard. The cache from Tiberias includes eight braziers. They all have signs of soldered feet on the base. One of them has traces of a cylindrical receptacle in its center, which resulted in researchers misidentifying the group as candlesticks.28

The square brazier was far more popular and, as mentioned above, was used during social events such as outings. The round brazier was used for slow cooking; since it remained in the home, it does not appear in contemporary documents.

Both types are still in use today. The square brazier, made of simple hammered tin, is very popular for outdoor events in the Middle East. A subtype of the large brazier is found in traditional Eastern cooking. Today it is made of stainless steel and is heated by a gas canister sufficient for the long slow cooking of fava beans. This was probably the function of the large brazier originating from Caesarea. The smaller ones were used to cook beans, rice, and sauces.

Feet and Handles

Continuous typological adaptation affected not just vessels and cooking articles but also minor items such as feet and handles of vessels. Vessel feet from the Greek, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods are based upon the paw- or hoof-shaped leg, which continues with variations into the Islamic period (see fig. 29.5a). For example, a bronze throne leg dated from the sixth to the fourth century BC is characterized by its lion-paw shape.29 A box or cista with the figure of Heracles fighting a snake, now in the British Museum, is supported by three cloven hoof–shaped feet; the box is dated to the late fourth to the third century BC. A lampstand with lion’s legs dated to the first century AD is also in London.30

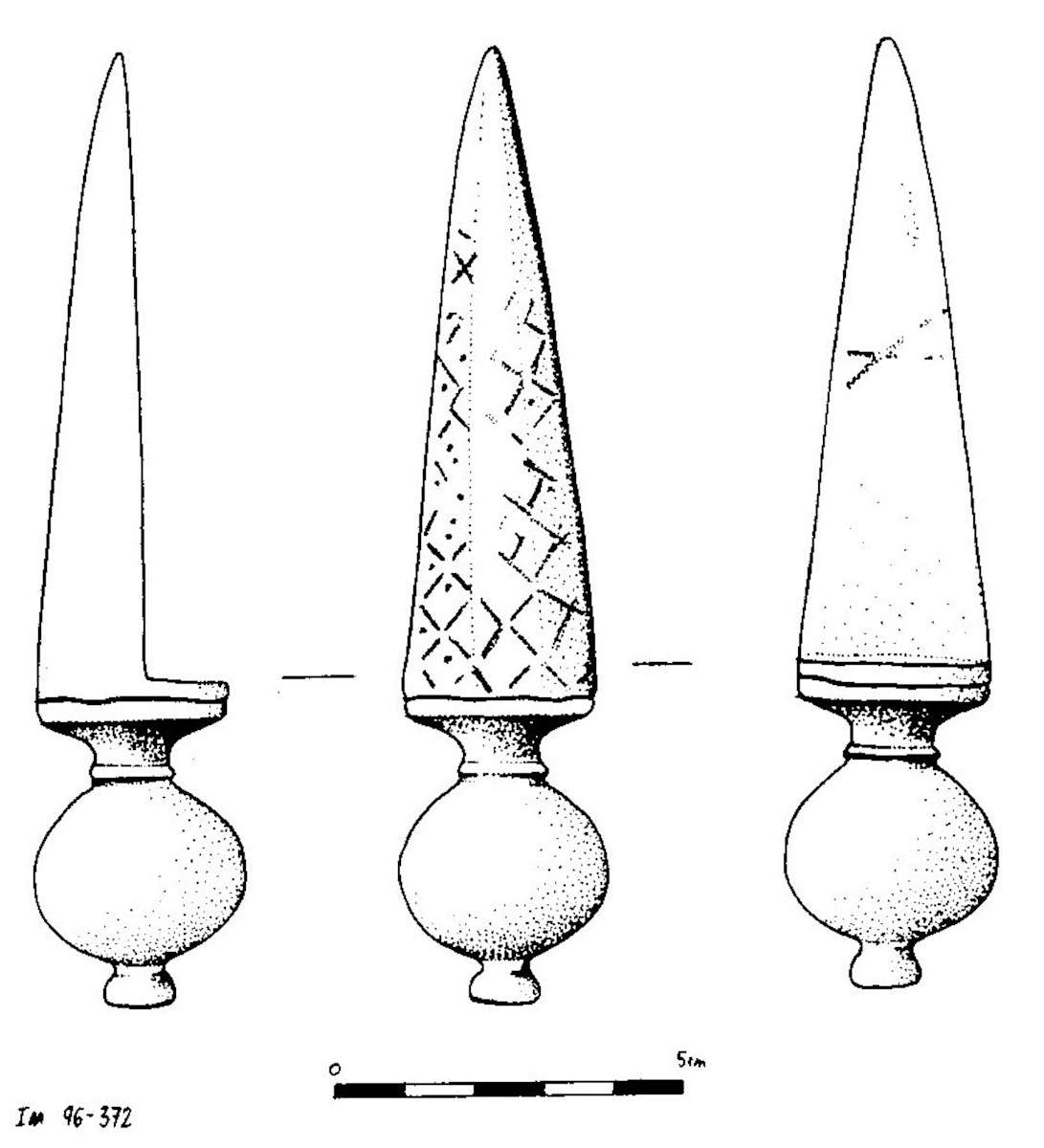

A base of a lampstand, with three hoof-shaped feet with protruding lion paws, is dated to the Roman period.31 A lampstand dated to the sixth to seventh century has three feet in the shape of griffin’s heads.32 During the Islamic period, the naturalistic shape was transformed into a symbolic pattern that often only insinuates the original shape. The small feet that were used to raise a vessel above the floor have undergone a change. During the Classical period, they bore a motif of a cloven hoof with a recess on which the vessel rested; now they have become entirely stylized (fig. 29.6), sometimes even being identified as a spike rather than a foot.33 This reflects the religious ban on the use of figural sculpture and exemplifies its effect on the consolidation of Islamic material culture.

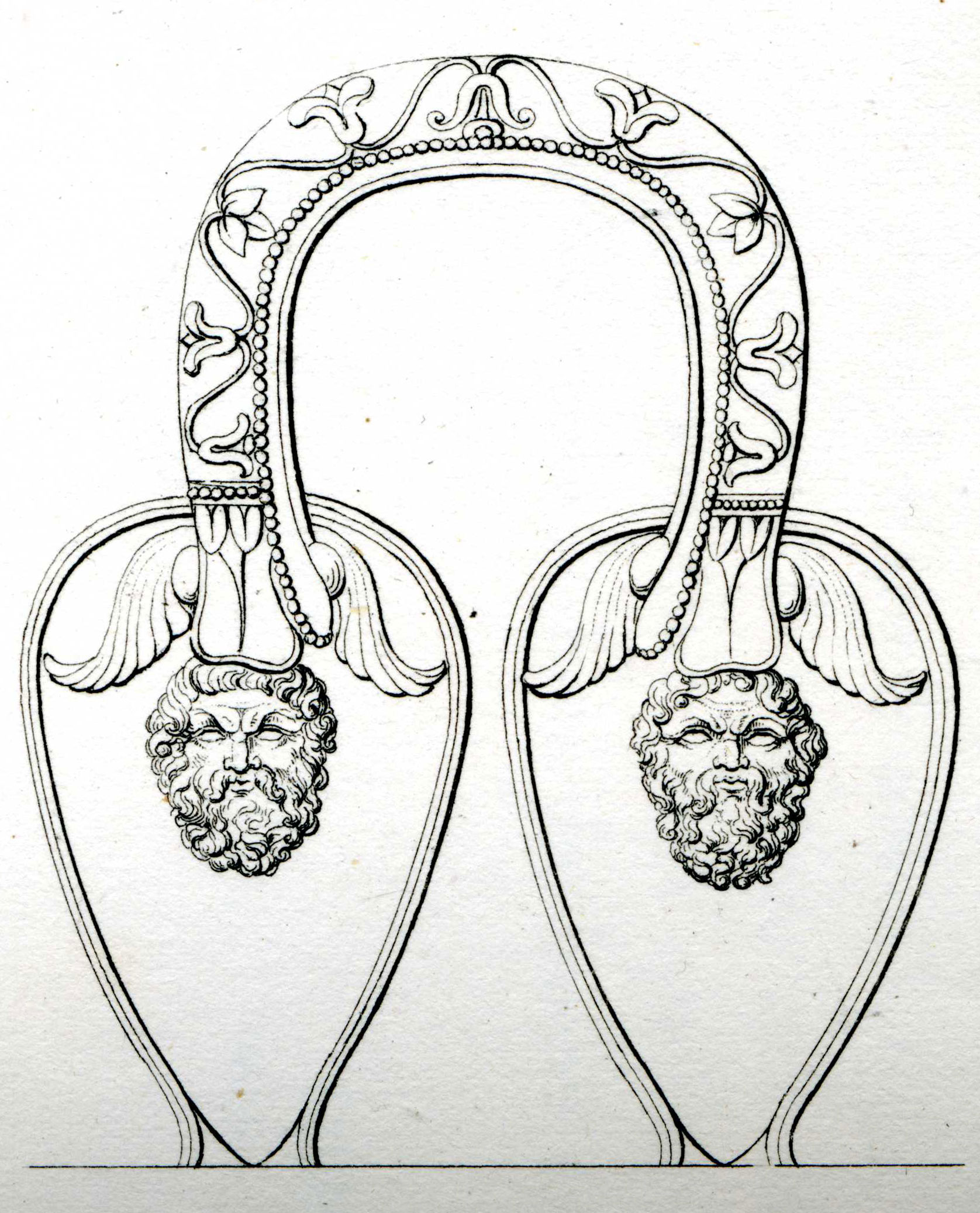

The same effect apparently applied to arch-shaped handles. The tips of the handles change into simple almond-shaped terminations, thus becoming functional rather than decorative (fig. 29.7a).34 This is a substantial change from earlier handles, which were decorated on the edges with animals, faces of men, ivy leaves, and fruits (fig. 29.7b).

Summary

This paper has surveyed typological changes of vessels and other artifacts from the Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods, up to the Fatimid period during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, over a period of more than 1,700 years. Four different groups of vessels were dealt with: lampstands, saucepans, braziers, and feet and handles. They were continuously in use and maintained their broad typological outlines while undergoing morphological changes over the years. The most prominent difference between Byzantine lampstands and Fatimid ones is the replacement of the round canopy-shaped base and the replacement of the upper pricket with a large tray. Although they were found at Tiberias, metal lamps during the Islamic period are rare in comparison to the huge quantities of clay lamps that were placed on the metal trays. This is clearly shown in a miniature from Kitab al-Diryāq (Book of Antidotes) by Pseudo-Galen, dated 1199, in which the writer is presented with a lampstand bearing a lamp made of glazed clay, typical of the Ayyubid-Mamluk period.35 The saucepans, which we suggest are measuring vessels for grain, became trapezoidal in shape and were sometimes decorated with a band of half palmettes, tendrils, and benefactory inscriptions in Arabic. The square brazier subtype continues a Roman tradition. The round subtype has no known prototypes from the Roman and Byzantine periods, but it remained within the typological repertoire and reappeared during the Fatimid era. It should be mentioned that the major influence within the group of metal vessels is from Egypt, during the Roman and Byzantine periods, where there was an established tradition of metal production. The groups of feet and handles exemplify the fundamental consolidation of Islamic material culture. They refrain from any sculpture-like identity and schematize decorative elements into functional shapes that distance themselves from the prototype. This change most likely occurred during the Abbasid period with the establishment of the Islamic regime.

Notes

- Ettinghausen 1943, fig. 2; Jones and Mitchell 1976, nos. 157, 166; Fehérvari 1976, plates 2, 2a; Brend 1991, fig. 16; Enderlein 2003, 27–28. ↩

- Bloom and Blair 1997, nos. 65–67; Melikian-Chirvani 1982, 7–22; Allan 1983. ↩

- The Fatimid dynasty emerged from North Africa in 909, conquered Egypt in 969, and founded Cairo as its capital. It took its name from Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad, from whom they claimed descent and adopted the Ismaili branch of Shi’ite belief. They subdued and ruled Sicily, Syria, Palestine, Hejaz, and Yemen. The Fatimid rulers established a strong administrative and financial apparatus with extensive revenues arising from taxes, trade, and an influx of gold from the Nubian mines; see Canard 1965. ↩

- Ettinghausen and Grabar 1987, 167–208; Contadini 1998; Institut du monde arab 1998; Ettinghausen, Grabar, and Jenkins-Madina 2001, 187–215; Bloom 2007. ↩

- Fehérvari 1976, 39–54; Baer 1983, 13, fig. 5; Allan 1985; Ward 1993, 60–69; Seipel 1998, 65–72. ↩

- Lester 2011; Lester 2014. ↩

- Khamis 2013. ↩

- Gil 1983, 338; Bijovsky and Berman 2008. ↩

- Bailey 1996, nos. Q3863, Q3864. ↩

- Bailey 1996, nos. Q3873, Q3874, fig. 2a. ↩

- Bailey 1996, nos. Q3870, Q3876. ↩

- Bailey 1996, no. Q3911, pls. 126–27. ↩

- Ross 1962, no. 39. ↩

- Bailey 1996, nos. Q3920, Q3921, pls. 134–5. ↩

- Ross 1962, no. 38; Weitzmann and Frazer 1979, no. 556; Bailey 1996, nos. Q3920, Q3921, plates 134–35. ↩

- Bailey 1996, no. Q3912 EA, pl. 134. ↩

- Tassinari 1993, 98, no. 8689. ↩

- Wulff 1909, plate LII, nos. 1031–32. ↩

- Hayes 1984, no. 182. ↩

- Fehérvari 1976, no. 23; Khamis 2013, 75–76, nos. 356–61. ↩

- Bel 1995. ↩

- Goitein 1983, 141. ↩

- Irwin 1997, fig. 211. ↩

- Ward 1993, fig. 7. ↩

- Hillenbrand 1999, fig. 4; Dimand 1944, fig. 90. ↩

- Pieraccini 2003. ↩

- Rosenthal-Heginbottom 1981, 110–11. ↩

- Khamis 2013, 140–47. ↩

- Dayagi-Mendels and Rozenberg 2010, no. 91. ↩

- Bailey 1996, no. Q3870, pls. 102, 104. ↩

- Bénazeth 2008, no. 36. ↩

- Bailey 1996, no. Q3927 MLA, plate 137. ↩

- Davidson 1952, 1053, 1054, plate 72. ↩

- Ainé 1870, 165, plate 84; Hayes 1984, no. 38. ↩

- Baer 1983, 8, fig. 1. ↩

Bibliography

- Ainé 1870

- Ainé, H. R. 1870. Herculanum et Pompéi: Recueil général des peintures, bronzes, mosaiques, etc. Vol. 12. Paris: Librairie de Firmin-Didot.

- Allan 1985

- Allan, J. W. 1985. “Concave or Convex? The Sources of Jaziran and Syrian Metalwork in the 13th Century.” In The Art of Syria and the Jazīra 1100–1250, ed. J. Raby, 126–40. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Baer 1983

- Baer, E. 1983. Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art. Albany: State University Press of New York.

- Bailey 1996

- Bailey, D. M. 1996. A Catalogue of the Lamps in the British Museum. Vol. 4: Lamps of Metal and Stone and Lampstands. London: The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Bel 1995

- Bel, A. 1995. s.v. “Sā‘.” Encyclopaedia of Islam 7: 654. 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill.

- Bénazeth 2008

- Bénazeth, D. 2008. Catalogue général du Musée copte du Caire. Vol. 1: Objets en metal. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologique orientale.

- Bijovsky and Berman 2008

- Bijovsky, G., and A. Berman. 2008. “The Coins.” In Tiberias: Excavations in the House of the Bronzes. Vol. 1: Architecture, Stratigraphy, and Small Finds, ed. Y. Hirschfeld and O. Gutfeld, 63–105. Qedem 48. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Bloom 2007

- Bloom, J. M. 2007. Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Bloom and Blair 1997

- Bloom, J. M., and S. Blair. 1997. Islamic Arts. London: Phaidon.

- Brend 1991

- Brend, B. 1991. Islamic Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Canard 1965

- Canard, M. 1965. s.v. “Fātimids.” Encyclopaedia of Islam 2: 850–52. 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill.

- Contadini 1998

- Contadini A. 1998. Fatimid Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V&A Publications.

- Davidson 1952

- Davidson, G. R. 1952. Corinth. Vol. 12: The Minor Objects. Princeton, NJ: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

- Dayagi-Mendels and Rozenberg 2010

- Dayagi-Mendels, M., and S. Rozenberg. 2010. Chronicles of the Land: Archaeology in the Israel Museum Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum.

- Dimand 1944

- Dimand, M. S. 1944. A Handbook of Muhammadan Art. New York: Hartsdale House.

- Enderlein 2003

- Enderlein, V. 2003. Museum of Islamic Art: State Museums of Berlin, Prussian Cultural Property. Trans. R. H. Barnes. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Ettinghausen 1943

- Ettinghausen, R. 1943. “The Bobrinski ‘Kettle’: Patron and Style of an Islamic Bronze.” Gazette des Beaux Arts 24: 193–208.

- Ettinghausen and Grabar 1987

- Ettinghausen, R., and O. Grabar. 1987. The Art and Architecture of Islam, 650–1250. Pelican History of Art. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, and New York: Penguin.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar, and Jenkins-Madina 2001

- Ettinghausen, R., O. Grabar, and M. Jenkins-Madina. 2001. Islamic Art and Architecture, 650–1250. 2nd ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Fehérvari 1976

- Fehérvari, G. 1976. Islamic Metalware of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection. London: Faber and Faber.

- Gil 1983

- Gil, M. 1983. Palestine during the First Muslim Period (634–1099) (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University and the Ministry of Defense.

- Goitein 1983

- Goitein, S. D. 1983. A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Vol. 4, Daily Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hayes 1984

- Hayes, J. W. 1984. Greek, Roman, and Related Metalware in the Royal Ontario Museum: A Catalogue. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum.

- Hillenbrand 1999

- Hillenbrand, R. 1999. Islamic Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Institut du monde arabe 1998

- Institut du monde arabe. 1998. Trésors fātimides du Caire. Exh. cat. Paris: Institut du monde arabe.

- Irwin 1997

- Irwin, R. 1997. Islamic Art. London: Laurence King.

- Jones and Mitchell 1976

- Jones, D., and G. Mitchell, eds. 1976. The Arts of Islam. Exh. cat. London, Hayward Gallery. London: Arts Council of Great Britain.

- Khamis 2013

- Khamis, E. 2013. Tiberias: Excavations in the House of the Bronzes. Vol. 2: The Fatimid Metalwork Hoard from Tiberias. Qedem 55. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Lester 2011

- Lester, A. 2011. “Typological and Stylistic Aspects of Metalware of the Fatimid Period” (Hebrew with an abstract in English). 2 vols. PhD thesis, University of Haifa.

- Lester 2014

- Lester, A. 2014. “Reconsidering Fatimid Metalware.” Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Warsaw 2012, ed. Piotr Bieliński et al., 437–54. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Melikian-Chirvani 1982

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. 1982. Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World: 8th–18th Centuries. Victoria and Albert Museum Catalogue. London: HMSO.

- Pieraccini 2003

- Pieraccini, L. C. 2003. Around the Hearth: Caeretan Cylinder-stamped Braziers. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Rosenthal-Heginbottom 1981

- Rosenthal-Heginbottom, R. 1981. “Notes on Hellenistic Braziers from Tel-Dor.” Qadmoniot 55/56: 110–11.

- Ross 1962

- Ross, M. C. 1962. Catalogue of the Byzantine and Early Medieval Antiquities in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection. Vol. 1: Metalwork, Ceramics, Glyptics, Painting. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Seipel 1998

- Seipel, W. 1998. Schätze der Kalifen: Islamische Kunst zur Fatimidenzeit. Exh. cat. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

- Tassinari 1993

- Tassinari, S. 1993. Il vasellame bronzeo di Pompei. 2 vols. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Ward 1993

- Ward, R. 1993. Islamic Metalwork. London: British Museum.

- Weitzmann and Frazer 1979

- Weitzmann, K., and M. E. Frazer. 1979. Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century. Exh. cat. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Wulff 1909

- Wulff, O. 1909. Altchristliche und mittelalterliche byzantinische und italienische Bildwerke. Part 1: Altchristliche Bildwerke. 2 vols. Berlin: Reimer.