17. Roman Bronze Figurines of Deities in the National Archaeological Museum of the Marche (Ancona)

- Nicoletta Frapiccini, Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici delle Marche, Ancona

Abstract

The collection of Roman bronze statuettes in the National Archaeological Museum of the Marche at Ancona includes numerous representations of deities. The majority of these statuettes are probably from domestic lararia in the territory, which in ancient times belonged to the regiones of Umbria and Piceno. This paper analyzes some of the most interesting statuettes, including the bronze figurines from Sentinum, where a foundry is known to have existed.

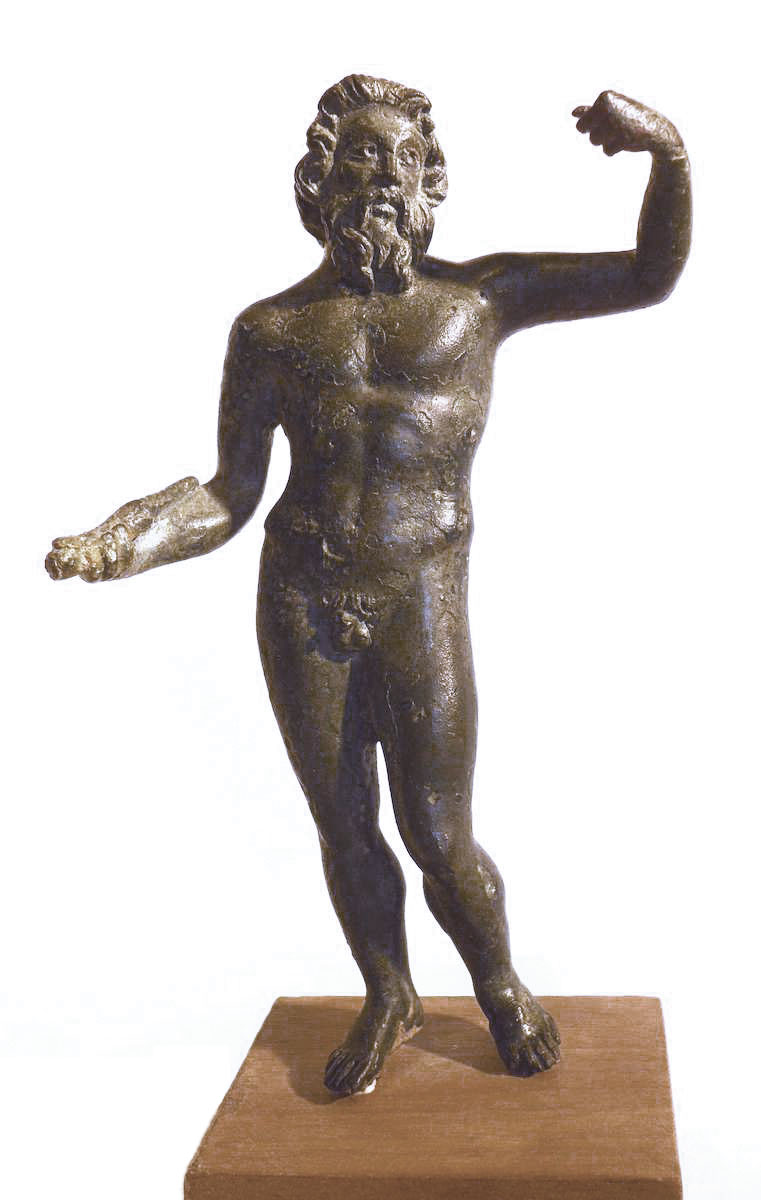

The first statuette represents Jupiter (fig. 17.1) and was found in Piandimeleto (Pesaro e Urbino) in 1933.1 It is a bronze statuette of appreciable quality and the subject is rendered following a well-known iconographic scheme, in this case adhered to quite faithfully: the figure is nude, standing with the weight on the right leg, with the left bent and placed behind; the right hand grasps a thunderbolt, the left arm would originally have rested on a scepter. The posture and demeanor identify it as the Type I of Kaufmann-Heinimann, replicated in numerous examples;2 to these we may add also bronze figurines with inverted posture, where the switch of the supporting leg may be a simple variant. The common prototype, replicated at times with considerable liberty, may be recognized in the statue of Zeus Brontaios by Leochares, which has been identified in the marble replicas of Zeus of the Ince Blundell and Cyrene types.3 Our bronze figurine presents a marked suppleness of the bust, a well-rendered softness in the modeling, and a variation in the position of the head, which is directed upward and toward the scepter, rather than down toward the thunderbolt, as in most cases.4 The hair, perhaps originally bound by a taenia in a different material, descends from the summit of the head in flat, wavy locks, which rise in a sort of anastolè or upswept hair over the forehead, increasing in volume around the face and above the neck; this is quite different from the more widespread thick-ringed locks. The closest analogies would be the head of Zeus from Vieil-Evreux5 and the Jupiter of Gran San Bernardo,6 while the mustache and beard appear to have soft lines, similar to those of a head of Zeus at the Liebieghaus in Frankfurt,7 sharing also the slightly pathetic facial expression. These details and the analogous works suggest a date after the end of the first century AD, but not later than the first decades of the second century.

This bronze statuette was found by chance in Piandimeleto, in the area of Castellaro/Cabuccaro, at a site that has never been excavated, and we may only hypothesize that it belonged to the lararium of a villa.8 Agriculture, forestry, and sheepherding were common occupations in this area, as were quarrying and artisan activities, thus there were certainly some villas or rustic settlements.9 It is also possible that the statuette suggests the existence of a sacred area, perhaps connected with the local mineral waters, which were held to have medicinal properties.10 The quality of this statuette testifies to the circulation of well-made artifacts in this territory, which was perhaps not completely closed within its own microsystem of roads.11 In fact, the site is located between Sestinum (a veritable crossroads) and Pitinum Pisaurense (Maceratafeltria), along a road that connected the valley of the Pisaurus (Foglia) River with that of the Tiber by way of the Viamaggio pass, a route that led to Arretium (modern Arezzo) and hence to Rome. The area was therefore open to the circulation of goods, influences, and models.

A second statuette, of unknown provenance, portrays a majestic Jupiter (fig. 17.2) in a markedly modest version of the “Florence type Zeus,”12 which is considered, even in the most recent studies, to be derived from an iconographic model dating to a Greek original in the late Severe style, identified with the Zeus of Myron at the Heraion of Samos.13 This latter artifact, placed on the Capitoline by Augustus, must have had considerable influence on later representations of the god, which would explain its widespread distribution among small bronze statuettes. This statuette is a far cry from that precious model and constitutes an impoverished and simplified version thereof, which is attested in many other examples.14 The rendering of our example is quite rough and approximate, and the patina is highly inhomogeneous: these observations, along with the fact that the area of discovery is unknown, go so far as to throw doubt on its authenticity.15

Also unknown is the provenance of a statuette of Mercury with petasos and a chlamys folded in a triangle (fig. 17.3). It represents the god according to a widespread model of Polykleitan tradition, inspired by the Doryphoros, but the result of mediation with Late Hellenistic or Roman experiences.16 Undeniable Polykleitan reminiscences emerge through the stance, the rendering of the torso muscles, the position of the head and the hair, with the characteristic “pincer” locks. It may be attributable to Annalis Leibundgut’s London–Copenhagen group, being closer to the Copenhagen variant, which is more dependent upon the Doryphoros.17 There are clear analogies between our bronze statuette and those found in Italy and beyond the Alps, above all in southern Gaul,18 especially with the exemplars from Trento, Trieste, Waldenburg, and Augst.19 The soft modeling and the calibrated a freddo workmanship, which can be appreciated above all in the rendering of the chlamys, would suggest a date probably no later than the end of the first century AD.20

A second bronze statuette of Mercury (fig. 17.4) was found by chance in Castelfidardo (Ancona),21 not far from the municipium of Auximum (modern Osimo), along a road that led toward the coast to the Roman cities of Ancona and Potentia (modern Porto Recanati-Macerata).22 A rustic villa was discovered at the same site some years later;23 it was concluded that the bronze statuette must have belonged to its lararium. The presence of a lotus leaf suggests an identification with Mercury-Toth, a Hellenistic creation, probably Egyptian, which was very widespread especially from the time of Augustus and in the mid-Imperial age.24 In terms of its general lines, the iconographic scheme of the statuette would appear inspired by a model influenced by Polykleitos. However, the statue reveals also the rhythms of fourth-century BC sculpture, both for its spatial layout and the rendering of the anatomy, which is quite disharmonic. The layout of the chlamys is typical of the Hermes Richelieu and the Praxitelean Hermes Andros-Farnese types,25 as is the hair, which shows Late Classical influences, with a double row of ringed curls.26 The rendering, which is commonplace and in some points quite poor, nevertheless reveals a taste for marked, rippled modeling, together with dynamic aspects in the position of the body,27 which were particularly appreciated from the period of Claudius onward. These considerations, supported by the context of its provenance, suggest a date between the second half of the first century and the beginning of the second century AD.

Two more bronze statuettes were found by chance in Orciano di Pesaro and Montebello Metaurense in 1923.28 The first represents Diana (fig. 17.5),29 one of a large series of bronze statuettes of the goddess as venatrix, with bow and arrows, in a static position.30 The Polykleitan stance, derived from the Amazon type, is conjoined with later features, such as the short chiton with a long apoptygma. The calm stance of the statue is reminiscent of analogous examples, and it is attributable to a model close to the Diana of the Ostia–Berlin–Copenhagen type.31 This statuette also presents a peculiar position of the head, turned toward the right hand, and a hairstyle with diadem, quite similar to the Artemis of Versailles, rather than the more common knot of the Rospigliosi Artemis,32 which is more frequently replicated in bronze statuettes. With its eclectic character, the sobriety of the surface treatment, and the hairstyle, the statuette may be still datable to within the first century AD.

The second figurine from Montebello Metaurense, close to the river Metauro, represents Victory atop a globe (fig. 17.6). This example seems to depart from the typical iconographic scheme for bronze figurines of this deity, which usually were inspired, more or less liberally, by the statue of Victory dedicated in Taranto and placed by Augustus in the Curia Iulia in 29 BC.33 Instead of the goddess dynamically posed in flight, she is here represented standing with her weight on her right leg, with the left extended forward and a himation wrapped around her legs. This detail reveals iconographic models of Late Hellenistic influence, also observable in the slender proportions of the figure. Only the measured twist of the bust toward the left, culminating in the head, gives the figure a slight sense of upward thrust, perhaps reminiscent of Hellenistic rhythms. This iconography has analogies in some coinage dating to the end of the third and beginning of the second century BC (where the globe, however, is absent), and on coins from AD 69.34 The decidedly eclectic character and the rendering of the clean, well-defined fabric folds suggest a date in the mid- to late first century AD.

The provenance of the two examples from nearby sites along the Via Flaminia,35 the road connecting the Adriatic coast with Rome, perhaps explains their peculiarity. It is quite possible that along this road there traveled not only trade goods but also bronze figurines, their molds or their models, and it is likely that there were local workshops. It is worth remembering that the exquisite bronze statuette of Victory in flight on a globe, today in Kassel, came from the nearby Forum Sempronii.36

It is plain that the iconographic scheme of all our statuettes, while often displaying the characteristic autonomy of these Kleinbronzewiederholungen (small bronze copies), nevertheless reveals a dependence on prototypes, even when these are liberally influenced by the predominant taste for eclectic creations.37 The figurines also testify that artisans took up models, often quite swiftly, that became part of the figurative repertory of small statue production, and that the mid-Adriatic elite kept up with the prevailing contemporary tastes.

Finally, an exceptional discovery is the group of bronze figurines from Sentinum (Sassoferrato, Ancona).38 Among these is a statuette of Minerva, found in the excavations in the northwest quarter of Sentinum in 1960, close to a room identified as a foundry (fig. 17.7). This excavation uncovered a large number of Imperial-age pottery fragments in the same context, supporting the dating of the statuette to the second century AD.39 In the nearby room of the foundry, numerous finds in bronze had already been uncovered in 1954, among which were a large number of utensils (fig. 17.8). There were numerous small spatulas, 109 scrapers, 66 pieces of slag, 102 rods and portions of sprues, 4 dowels, 4 rods for dowels, 9 portions of wire, and 4 pairs of pliers. Inside the foundry, finds included many fragments of bronze objects, plaques, waste pieces of cut bronze foil, little fragments of a gilded-bronze horse’s head, a finger of a statue, fragments of garments from statues, and unfinished objects.

In 1997–98 Giuliano de Marinis conducted new excavations to clarify the nature and use of this building. The exploration, though only partial, highlighted a complex stratigraphic sequence, from the Late Antique to the Late Republican age.40 The identification of probable traces of wooden stairs on the southern wall of a room argues for the existence of an underground level. The excavation was unfortunately interrupted, and a comprehensive layout of the building, which was located in an area dedicated to artisan activities, has yet to be completed.41 Therefore, although these rooms are now almost certainly identifiable as belonging to a foundry, its size and layout have yet to be outlined. This information would be useful to determine whether its function was to create large statues during the Roman age, as Giuliano de Marinis supposed,42 or just small votive and other bronze objects up to the Late Antique period. The fact that metallurgy was widely practiced in Sentinum and its territory is also confirmed by the much older finds of bronze figurines from archaic sanctuaries, which are associated with local workshops.43 These, located in Sassoferrato and the nearby San Fortunato di Genga, testify to the existence of a strong tradition of small-scale bronze sculpture in the area, with roots dating back to an era long before Romanization.

Notes

- Soprintendenza Archeologia delle Marche, A.V.S., cassetta 6 bis, fascicolo 1. See Galli 1946–48, 3–8. ↩

- Kaufmann-Heinimann 1977, 17–18, no. 1, plate 1. See particularly the Jupiter from Paramythia, Epiro (LIMC 8: 432, no. 116, plate 278); the statuette from Köln (Menzel 1984, 191, plate 20); the statuette in Paris (LIMC 8: 430–31, no. 91, plate 275); the statuette in the Historisches Museum Basel (Kaufmann-Heinimann 1977, 18, no. 1, plate 1); and the Jupiter from Verona in Bruxelles (Bolla 1999, 199, plate 1). ↩

- See also Beschi 1962, 75–76; Boucher 1976, 70–77; Menzel 1984, 190–91; LIMC 8: 339, no. 195, plate 227. ↩

- For the positioning of the head toward the scepter, see the Jupiter from Muri (Bern), with inverted schema (Leibundgut 1980, 16–17, no. 6, plates 11–13); a statuette of Jove in Florence (Muscillo 2015, 66–67, no. 5); and the Jupiter from Montorio Veronese, with inverted position of the arms (Beschi 1962, 75; Bolla 1999, 197–99, plate 2). Regarding the liberty taken in the replication of such archetypes, see D’Andria 1978, 21–31; Leibundgut 1980, 9; Menzel 1984; Koortbojian 2015, 47–48. ↩

- Menzel 1984, 188, plates 9–12. ↩

- Leibundgut 1980, 14–16, plates 4–9. ↩

- Dörig 1964, 262–66; LIMC 8: 340, no. 196a, plate 228. ↩

- About the lararia, see Adamo Muscettola 1984; Kaufmann-Heinimann 1998; Cadario 2015, 54–56. ↩

- On some sporadic discoveries in the area, see Monacchi 1995, 109, nos. 69–74. ↩

- Lombardi and Mazzarini 1995, 67–80. ↩

- Mario Luni argues otherwise: Luni 1995, 93–100; Luni 2003, 199–200. ↩

- Kaufmann-Heinimann (1977, 17–18, no. 2, pls. 2–3) attributes this statuette to Type II. See the further analysis in Leibundgut 1980, 9–13, no. 1, pls. 1–2. ↩

- Berger 1969, 66–92. Iozzo (2015, 63–65, no. 1), accepting Berger’s interpretation, presents a survey of the hypotheses on the prototype. Some scholars attribute the prototype to Pheidias or his school, while others hold it to be a classicistic creation of the Hadrianic period (Neugebauer 1935, 321; Beschi 1966–67, 60; Leibundgut 1980, 12–13). ↩

- Leibundgut (1980, 9–13, no. 1, pl. 1–2) distinguished two groups, attributing to the first the statuettes of higher quality and larger dimensions, while to the second, the replicas of smaller dimensions and commonplace workmanship, to which our example may be attributed. ↩

- See analogous observations for the series of Mercury with paenula: Bolla 1997, 38–39, no. 7, pl. 4. ↩

- On this problem, see Beschi 1993. ↩

- Leibundgut 1990, 405–12, no. 195. See also Kaufmann-Heinimann 1977, 29, Type III. ↩

- Boucher 1976, 81–84, pls. 32, 142–44, map no. X. ↩

- Walde Psenner 1983, 42, no. 12 (Trento); Cassola Guida 1978, 76, no. 60 (Trieste); Kaufmann-Heinimann 1977, nos. 27–28, pls. 17–19 (Waldenburg and Augst). ↩

- See also Leibundgut 1990, 411–12. ↩

- Frapiccini 2005a, 174, no. 90. ↩

- Gentili 1990, 20. ↩

- Mercando 1979, 132. ↩

- See Kaufmann-Heinimann 1994, 15–16, no. 12; LIMC 6: 508, no. 43–45, plates 276 and 535; Capriotti Vittozzi 1999, 206–9. ↩

- LIMC 5: 367–68. ↩

- See the head of the statuette of Mercury in Verona (Franzoni 1973, 58, no. 38). ↩

- Similar statuettes came from Milan (Bolla 1997, 41–42, no. 9, pl. iv), Trento (Walde Psenner 1983, 49–50, no. 21), Verona (Franzoni 1973, 56, no. 36), and Casteggio (Invernizzi 1996, 30–32, no. 1, pl. xviii, figs. 1a–c). ↩

- Soprintendenza Archeologia Marche, A.V.S. cassetta 6, fascicoli 1–2. ↩

- Pellati 1929, 502. ↩

- See the statuettes in Verona (Franzoni 1973, 86, no. 66) from Monteveglio (BO), in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (LIMC 2: 813, nos. 73, 75, plate 601), and in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence (Cianferoni 2015, 117, no. 79). ↩

- Picciotti Giornetti 1979, 23–24, no. 24 (statue from Ostia); LIMC 2: 802, nos. 18a–b. ↩

- LIMC 2: 805, no. 27, pl. 592 (Artemis of Versailles); 646, no. 274, pl. 468 (Rospigliosi Artemis). See also a statue of Artemis from Rome, datable at the time of Emperor Claudius, which presents a similar hairstyle and the same diadem: Paribeni 1981, no. 8. ↩

- Hölscher 1967, 6–16. ↩

- LIMC 8: 242, 18, pl. 168; Hölscher 1967, 18, pl. 1, fig. 5. ↩

- Luni and Mei 2013. ↩

- Luni and Mei 2014. ↩

- See Koortboijan 2015, 43–52. ↩

- Frapiccini 1998; Frapiccini 2005b; Frapiccini 2005c. ↩

- Fabbrini 1961, 320; Frapiccini 1998, 36–41, figs. 2–3. ↩

- Excavations of the Soprintendenza Archeologia delle Marche (not yet published). ↩

- Medri 2008, 212, fig. 3.1.10. ↩

- De Marinis 2003. ↩

- Colonna 1970; Frapiccini 2008; Frapiccini 2015, 595–98. ↩

Bibliography

- Adamo Muscettola 1984

- Adamo Muscettola, S. 1984. “Osservazioni sulla composizione dei larari con statuette in bronzo di Pompei ed Ercolano.” In Toreutik und figürliche Bronzen römischer Zeit: Akten der 6. Tagung über antike Bronzen, Berlin, 13–17 Mai 1980, ed. U. Gehrig, 87–94. Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Antikenmuseum.

- Arbeid and Iozzo 2015

- Arbeid, B., and M. Iozzo, eds. 2015. Piccoli Grandi Bronzi: Capolavori greci, etruschi e romani delle collezioni mediceo-lorenesi nel Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze. Florence: Edizioni Polistampa.

- Berger 1969

- Berger, E. 1969. “Zum samischen Zeus des Myron in Rom.” RM 76: 66–92.

- Beschi 1962

- Beschi, L. 1962. I bronzetti romani di Montorio Veronese. Memorie, Classe di Scienze Morali e Lettere 32. Venice: Istituto Veneto.

- Beschi 1966–67

- Beschi, L. 1966–67. “Una statuetta bronzea di Giove dai pressi di Verona.” BMusBrux 38–39: 45–62.

- Beschi 1993

- Beschi, L. 1993. “Bronzetti classicistici policletei: Alcune osservazioni.” In Bronces y religión romana: Actas del XI Congreso Internacional de Bronces Antiguos, ed. J. Arce and F. Burkhalter, 45–56. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

- Bolla 1997

- Bolla, M. 1997. Bronzi figurati romani nelle Civiche raccolte archeologiche di Milano. Notizie dal chiostro del Monastero maggiore, Supplemento 17. Milan: Civiche Raccolte Archeologiche e Numismatiche.

- Bolla 1999

- Bolla, M. 1999. “Bronzetti figurati romani del territorio veronese.” Rassegna di Studi del Civico Museo Archeologico e del Civico Gabinetto Numismatico di Milano 43/44: 193–260.

- Boucher 1976

- Boucher, S. 1976. Recherches sur les bronzes figurés de la Gaule pré-romaine et romaine. Paris: École française de Rome.

- Cadario 2015

- Cadario, M. 2015. “Le statuette in bronzo in contest tra culti, ornamenta e pezzi da collezione.” In Arbeid and Iozzo 2015, 53–59.

- Capriotti Vittozzi 1999

- Capriotti Vittozzi, G. 1999. Oggetti, idee, culti egizi nelle Marche: Dalle tombe picene al tempio di Treia. Picus, Supplemento 6. Tivoli: Tipigraf.

- Cassola Guida 1978

- Cassola Guida, P. 1978. Bronzetti a figura umana dalle collezioni dei Civici Musei di Storia ed Arte di Trieste. Venice: Electa.

- Cianferoni 2015

- Cianferoni, C. 2015. “Diana.” In Arbeid and Iozzo 2015, 117.

- Colonna 1970

- Colonna, G. 1970. Bronzi votivi umbro-sabellici a figura umana. Vol. 1: Il periodo arcaico. Rome: Sansoni.

- D’Andria 1978

- D’Andria, F. 1978. I bronzi romani di Veleia, Parma e del territorio parmense. Contributi dell’Istituto di Archelogia 3. Milan: Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

- De Marinis 2003

- De Marinis, G. 2003. “Produzioni bronzistiche romane nelle Marche.” In L’Uomo la Pietra i Metalli: Tesori della terra dal Piceno al Mediterraneo, ed. G. Capriotti Vittozzi, 156–57. San Benedetto del Tronto: Sfera.

- De Marinis 2005

- De Marinis, G., ed. 2005. Arte romana nei Musei delle Marche. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

- Dörig 1964

- Dörig, J. 1964. “Lysipps Zeuskoloss von Tarent.” JdI 79: 257–78.

- Fabbrini 1961

- Fabbrini, L. 1961. “Sentinum.” In Atti del VII Congresso Internazionale di archeologia classica, 315–23. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Franzoni 1973

- Franzoni, L. 1973. Bronzetti romani del Museo archeologico di Verona. Collezioni e Musei Archeologici del Veneto. Venice: Alfieri.

- Frapiccini 1998

- Frapiccini, N. 1998. “I bronzetti sentinati nel Museo Archeologico Nazionale delle Marche.” Picus 18: 31–61.

- Frapiccini 2005a

- Frapiccini, N. 2005. “Mercurio-Thot.” In De Marinis 2005, 174, no. 90.

- Frapiccini 2005b

- Frapiccini, N. 2005. “Iside-Fortuna.” In De Marinis 2005, 176, no. 92.

- Frapiccini 2005c

- Frapiccini, N. 2005. “Volto di Jupiter.” In De Marinis 2005, 200–201, no. 107.

- Frapiccini 2008

- Frapiccini, N. 2008. “Bronzetti votivi italici nel Museo Civico Archeologico di Sassoferrato.” In Sentinum 295 a.C. Sassoferrato 2006: 2300 anni dopo la battaglia: Una città romana tra storia e archeologia, Convegno Internazionale, Sassoferrato 21–23 settembre 2006, ed. M. Medri, 257–78. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Frapiccini 2015

- Frapiccini, N. 2015. “Bronzetti di produzione umbra nelle Marche.” In Gli Umbri in età preromana: Atti del XXVII Convegno di Studi Etruschi ed Italici, Perugia – Gubbio – Urbino, 27–31 ottobre 2009, 589–608. Pisa and Rome: Fabrizio Serra.

- Galli 1946–48

- Galli, E. 1946–48. “Il piccolo Giove di Pian di Meleto.” BullCom 72: 3–8.

- Gentili 1990

- Gentili, G. V. 1990. Osimo nell’antichità: I cimeli nella civica raccolta d’arte e il Lapidario del Comune. Bologna: Grafis.

- Hölscher 1967

- Hölscher, T. 1967. Victoria Romana: Archäologische Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Wesensart der römischen Siegesgöttin von den Anfängen bis zum Ende des 3. Jhs. n. Chr. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Invernizzi 1996

- Invernizzi, R. 1996. “Bronzetti figurati e instrumentum bronzeo da uno scavo a Casteggio.” Notizie dal chiostro del Monastero maggiore: Rassegna di studi del Civico museo archeologico e del Civico gabinetto numismatico di Milano 58: 29–45.

- Iozzo, M. 2015

- Iozzo, M. 2015. “Zeus.” In Arbeid and Iozzo 2015, 63–65.

- Kaufmann-Heinimann 1977

- Kaufmann-Heinimann, A. 1977. Die römischen Bronzen der Schweiz. Vol. 1: Augst und das Gebiet der Colonia Augusta Raurica. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Kaufmann-Heinimann 1994

- Kaufmann-Heinimann, A. 1994. Die römischen Bronzen der Schweiz. Vol. 5: Neufunde und Nachträge. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Kaufmann-Heinimann 1998

- Kaufmann-Heinimann, A. 1998. Götter und Lararien aus Augusta Raurica: Herstellung, Fundzusammenhänge und sakrale Funktion figürlichen Bronzen in einer römischen Stadt. Augst: Römermuseum.

- Kaufmann-Heinimann 2004

- Kaufmann-Heinimann, A. 2004. “Götter im Keller, im Schiff und auf dem Berg: Alte und neue Statuettenfunde aus dem Imperium Romanum.” In The Antique Bronzes: Typology, Chronology, Authenticity: The Acta of the 16th International Congress of Antique Bronzes, Organised by the Romanian National History Museum – Bucharest 2003, ed. C. Muşeţeanu, 249–63. Bucharest: Cetatea de Scaun.

- Koortbojian 2015

- Koortbojian, M. 2015. “Opera minora: Monumenta in miniatura?” In Arbeid and Iozzo, 2015, 43–52.

- Leibundgut 1980

- Leibundgut, A. 1980. Die römischen Bronzen der Schweiz. Vol. 3: Westschweiz, Bern und Wallis. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Leibundgut 1990

- Leibundgut, A. 1990. “Polykletische Elemente bei späthellenistischen und römischen Kleinbronzen: Zur Wirkungsgeschichte Polyklets in der Kleinplastik.” In Polyklet: Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik, ed. P. C. Bol, 397–427. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Lombardi and Mazzarini 1995

- Lombardi, F. V., and A. Mazzarini 1995. “Le acque minerali.” In Il Montefeltro. Vol. 1: Ambiente, storia, arte nelle alte valli del Foglia e del Conca, ed. G. Allegretti and F. V. Lombardi, 67–90. Verucchio: Comunità Montana del Montefeltro.

- Luni 1995

- Luni, M. 1995. “Il territorio dei municipi di Sestinum e Pitinum Pisaurense.” In Il Montefeltro. Vol. 1: Ambiente, storia, arte nelle alte valli del Foglia e del Conca, ed. G. Allegretti and F. V. Lombardi, 93–109. Verucchio: Comunità Montana del Montefeltro.

- Luni 2003

- Luni, M. 2003. Archeologia nelle Marche: Dalla preistoria all’età tardoantica. Florence: Nardini.

- Luni and Mei 2013

- Luni, M., and O. Mei, eds. 2013. Forum Sempronii. Vol. 2: La città e la Flaminia: 1974–2013. Urbino: Quattroventi.

- Luni and Mei 2014

- Luni, M., and O. Mei, eds. 2014. La Vittoria “di Kassel” e l’“Augusteum” di Forum Sempronii: Un ritorno nel bimillenario di Augusto. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Medri 2008

- Medri, M., ed. 2008. Sentinum: Ricerche in corso, vol. 1. Studia Archaeologica 162. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Menzel 1984

- Menzel, H. 1984. “Die Jupiterstatuetten von Bree, Evreux und Dalheim und verwandte Bronzen.” In Toreutik und figürliche Bronzen römischer Zeit: Akten der 6. Tagung über antike Bronzen, Berlin, 13-17 Mai 1980, ed. U. Gehrig, 186–96. Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Antikenmuseum.

- Mercando 1979

- Mercando, L. 1979. “Marche: Rinvenimenti di insediamenti rurali.” NSc 33: 89–296.

- Monacchi 1995

- Monacchi, W. 1995. “La carta archeologica.” In Il Montefeltro. Vol. 1: Ambiente, storia, arte nelle alte valli del Foglia e del Conca, ed. G. Allegretti and F. V. Lombardi, 101–25. Verucchio: Comunità Montana del Montefeltro.

- Muscillo 2015

- Muscillo, A. 2015. “Giove.” In Arbeid and Iozzo 2015, 66–67.

- Neugebauer 1935

- Neugebauer, K. A. 1935. “Zwei Jupiterstatuetten in Berlin und Weimar.” AA 1935: 321–34.

- Paribeni 1981

- Paribeni, E. 1981. “Statua di Artemide.” In Museo Nazionale Romano: Le sculture, part I, vol. 2, ed. A. Giuliano, 283–85. Rome: De Luca.

- Pellati 1929

- Pellati, F. 1929. “Notiziario archeologico: Fano, scoperte di antichità.” Historia 3: 502.

- Picciotti Giornetti 1979

- Picciotti Giornetti, V. 1979. “Statua ritratto di giovinetta: Tipo Artemide.” In Museo Nazionale Romano: Le sculture, part 1, vol. 1, ed. A. Giuliano, 23–24. Rome: De Luca.

- Walde Psenner 1983

- Walde Psenner, E. 1983. I bronzetti figurati antichi del Trentino. Patrimonio storico e artistico del Trentino 7. Trento: Assessorato alle attività culturali della Provincia Autonoma di Trento.