15. The Poet as Artisan: A Hellenistic Bronze Statuette in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Elizabeth McGowan, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts

Abstract

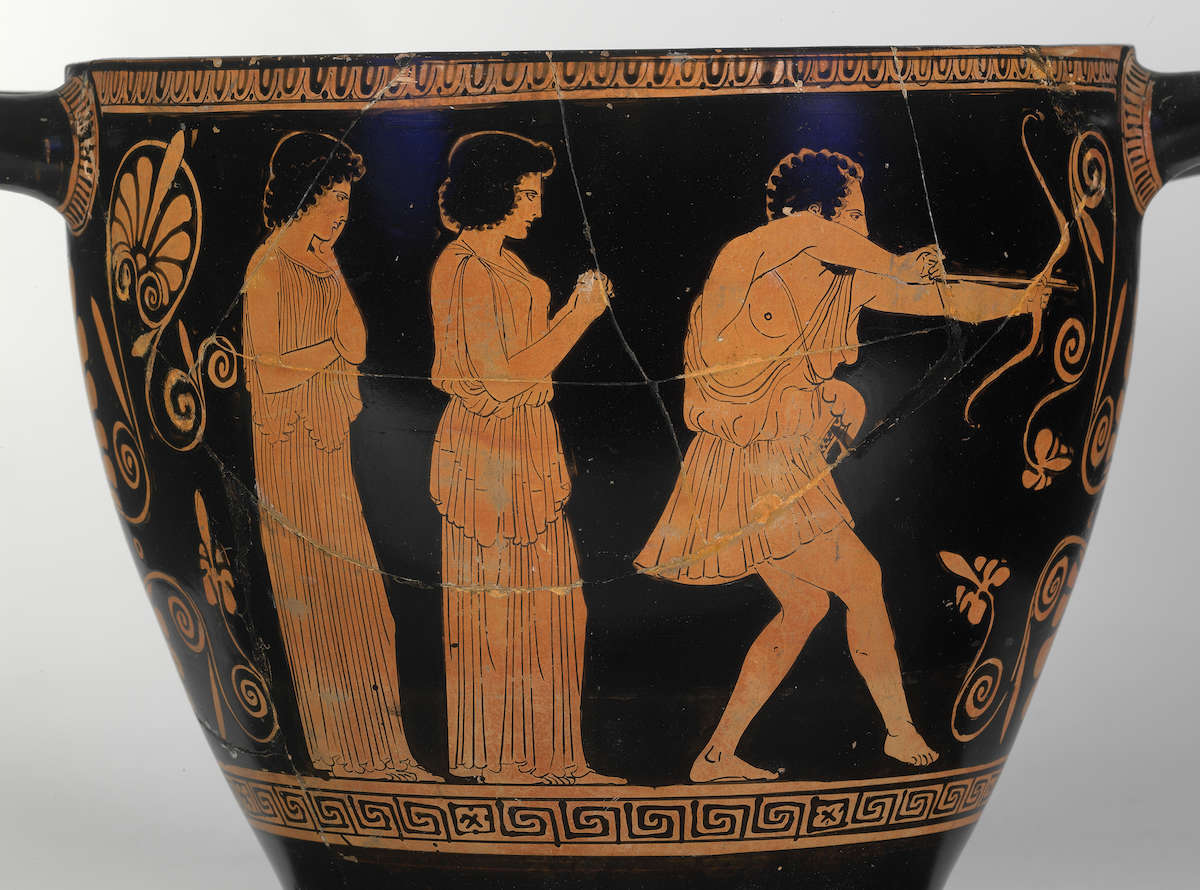

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1

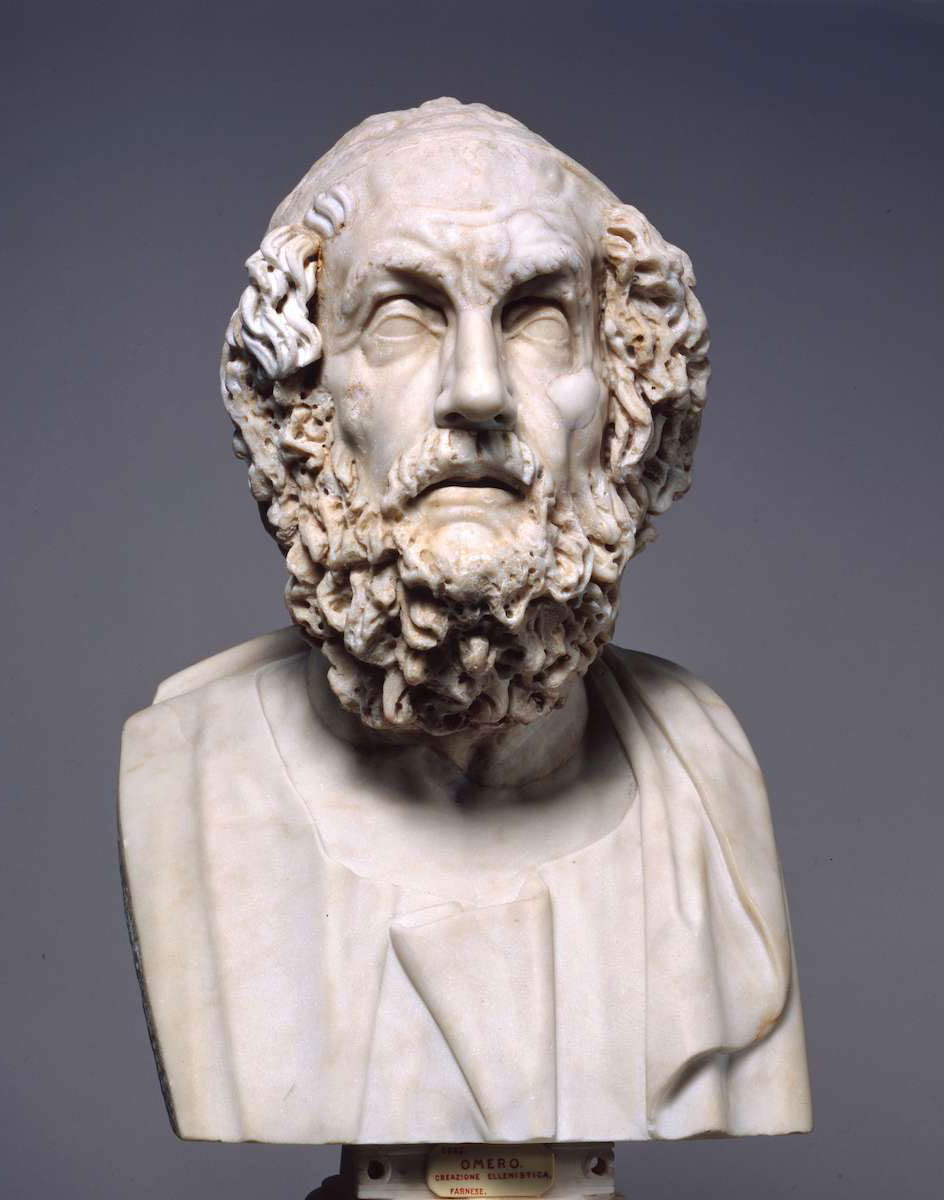

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

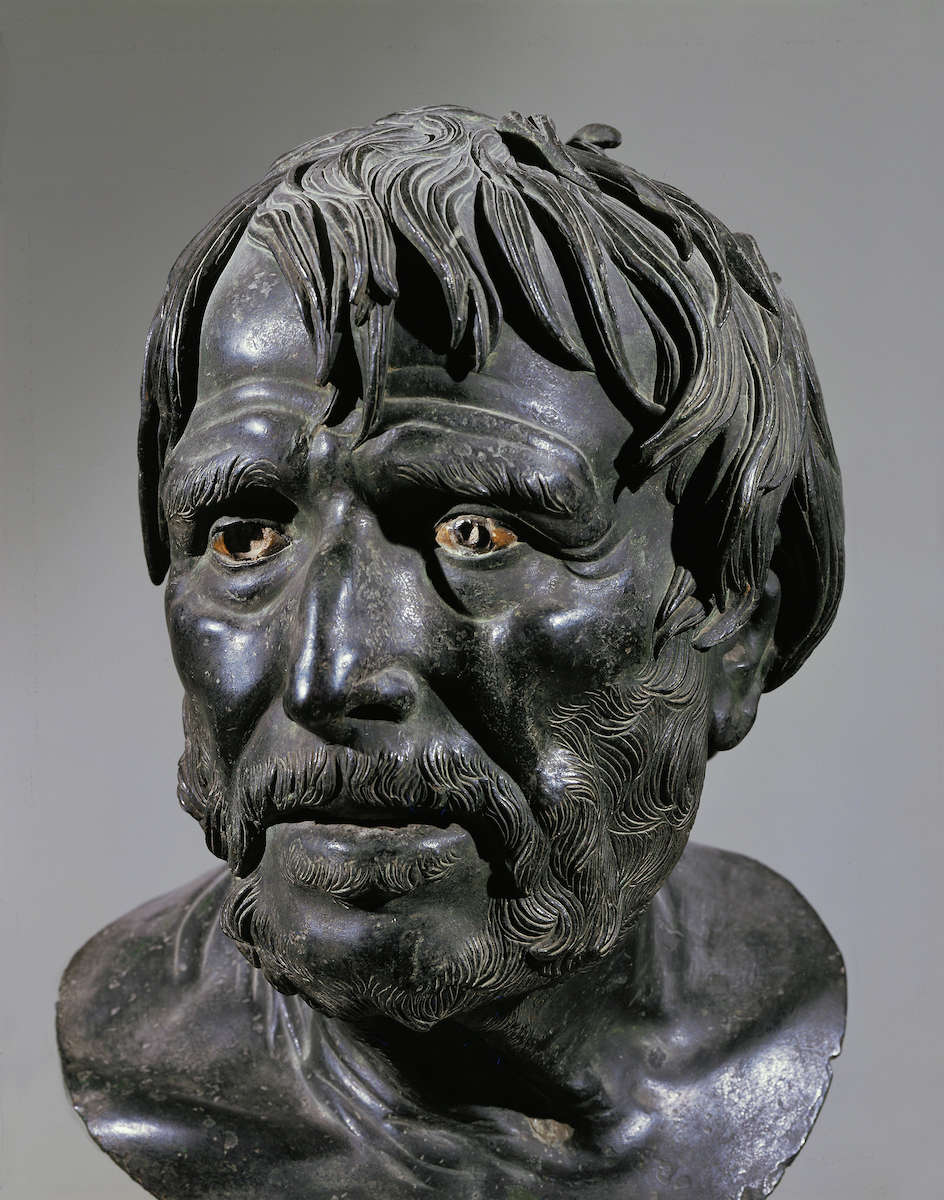

Figure 15.3

Figure 15.3

Many of the papers in this volume deal with the technical aspects of bronze manufacture and analysis of fabric and technique. But what of the artisans themselves? A large, relatively well-preserved Hellenistic bronze statuette in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, said to have been found off the coast of North Africa, appears to be an image of an artisan (fig. 15.1).1 He has been identified as such by his dress, his stocky build, and his hunched posture.2 Although missing its right arm and leg, the figure is well preserved. He appears to be short in stature, compact, and muscular. The well-defined, gnarled muscles of his left arm and leg, down to his bare feet, imply the physique of someone used to physical labor. His neck is short and his posture somewhat stooped and uneven, with rounded upper spine and right shoulder raised, as if years of working at a bench has resulted in scoliosis (fig. 15.2).3 His egg-shaped head seems large for his body and perhaps appears further elongated by the fact that, although he has curly hair at the sides and back of his head, he is balding on top (fig. 15.3). The figure’s brow is furrowed and his mouth has full, downturned lips set in a scruffy beard. He is far from canonically beautiful, yet the artist gave him silver eyes. The bright silver adds intensity to his gaze and imbues him with inner life and a certain nobility. This nobility seems at odds with the social status implied by his physical aspect and clothing. He wears an exomis, a short, belted garment that is fastened on one shoulder to allow the opposite arm maximum mobility, and in Greek art worn most often by artisans, laborers, slaves, and soldiers.4 Here the exomis is fastened on the right shoulder with a square knot, which would allow his left arm to move freely. At his full waistline, the exomis is secured with a belt with fringed ends, tied, again, in a square knot. Tucked behind the knot is a wax tablet, an attribute that sets this figure apart from the status of everyday workman. His left arm wraps across his body and might have supported the missing right arm, which has been imagined as bent at the elbow with its hand near the chin, a familiar gesture in antiquity of a figure deep in thought.5 Alternatively, his right hand might have held a staff or gripped a crutch tucked under his right arm.6

The unusual detail of silver eyes and the wax tablet seem tantalizing clues to the statue’s identity. Some have suggested that he might represent an historical figure while others propose that he belongs to the realm of myth. Stéphanie Boucher-Colozier, who first published the statuette, thought it might represent an imaginary portrait of Monimos, a cynic philosopher.7 Nikolaus Himmelmann recognized this bronze as an important example of Alexandrian realism, and noted correspondences between terracotta figures from Egypt and the figure’s clothing and gesture, especially among those he identified as cult attendants and waiting slaves.8 One Hellenistic terracotta figure thought to represent a slave, once in Leipzig and now lost, even had a wax tablet tucked behind the belt of his short chiton.9 Himmelmann alternatively suggested that the figure might represent the first sculptor in Greek myth, Daidalos.10 Other possible contenders are Epeios, the artist who made the Trojan horse, and even Hephaistos, as Seán Hemingway suggests, characterized by Homer as limping and not ideal in his features.11 He may even represent a mortal craftsman of great repute, such as Pheidias.12 All these interpretations point in the right direction. Here we have a figure who poses a conundrum: he seems like a person of some importance but does not represent an ideal. At the same time, he lacks the humorous exaggerations that one might expect in a true caricature. The figure seems outside the genre of realism that might reflect everyday characters.

We can narrow down his identity if we turn to the few attributes he possesses, starting with his clothing. He wears an exomis and is bare-headed as well as barefoot. Foremost among the mythological characters who wear the exomis is Hephaistos. As the Olympian god who is the patron of metalworkers, stonemasons, potters, and other craftsmen, he is often shown in either a short chiton or an exomis, and often with the tools of his trade: hammer, tongs, and torch for lighting the forge. In the tondo of the Foundry Painter’s name vase, Hephaistos wears a chitoniskos, with the sleeve unbuttoned to the top of his right shoulder to allow for freedom of movement (fig. 15.4). The fifth-century BC cult statue of Hephaistos in Athens, as reconstructed by Evelyn Harrison and others, is shown wearing an exomis.13 The image seems to be reflected on two terracotta Roman lamp discs, one in the Agora (fig. 15.5) and the other in the Athens National Museum (fig. 15.6).14 On both, Hephaistos wears an exomis and pilos (a workman’s felt hat) and holds a torch in his left hand. This type of image of the craftsman god appears on later Roman monuments, such as the figure of Vulcan carved in relief on a lower section of the Jupiter Column in Mainz (fig. 15.7).15 Here the god holds a hammer in his right hand and a torch in his left. Relying on the numerous echoes of the fifth-century statue in later art, Harrison concludes that the cult image wore the exomis tied on his left shoulder, so that his right arm could move freely and that his weight was on his right leg with his head turned slightly in that direction. The Hellenistic bronze statuette is in a mirrored position: the weight leg, the exposed arm, and the turn of the head all favor the left. And the Hephaisteion’s cult statue wore a workman’s hat, a felt pilos, while the bronze artisan is bare-headed.16 None of the preserved images of Hephaistos shows him with a wax tablet.

Daidalos also wears a one-shouldered chiton or an exomis in art. The few examples preserved are Roman. In a first-century Pompeian wall-painting, the sculptor wears a chitoniskos, with a sleeve on the left but the right arm free, as he presents the mechanical cow costume to Pasiphaë.17 A mosaic from the third-century Roman villa at Zeugma in southeast Turkey shows Daidalos in an exomis fastened on his left shoulder.18 Both images of the sculptor seem to reflect earlier Athenian images of Hephaistos. Daidalos is hatless, however, and in the case of the mosaic, he carries a saw in his right hand and a length of wood in his left, as Ikaros, also dressed in an exomis, works at a small table nearby. In two out of three scenes of the same story on a Late Roman sarcophagus in the Louvre, Daidalos wears an exomis with the right arm free. In one scene, he wears the exomis as he stands in contrapposto as he presents the cow to Pasiphaë. His drapery’s folds closely resemble those of many Roman representations of Hephaistos/Vulcan, such as that on the Jupiter Column from Mainz, where Vulcan’s pose recalls that of the highly influential Athenian cult statue of Hephaistos.19 The image of Daidalos that seems closest to the bronze artisan in dress appears on a relief in the Villa Albani, where the sculptor, seated in right profile at a table and bent over his work, crafts wings for himself and Ikaros.20 He wears an exomis that leaves his right shoulder and arm free. None of the examples shows Daidalos with a tablet.

Craftsmen of words might also wear the exomis. Odysseus, the great wordsmith of the Trojan epics, is shown in an exomis as early as the first quarter of the fifth century BC. On an Attic red-figure skyphos by the Penelope Painter, Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, takes aim with a bow and arrow at the suitors who have invaded his home (fig. 15.8). In Hellenistic and Roman art, Odysseus is often shown with the exomis and pilos.21 For example, a Roman statuette of Odysseus presenting a cup of wine (apparently to Polyphemos) also shows him wearing an exomis and pilos, as well as a short cloak (fig. 15.9).22

The Metropolitan’s bronze statuette has affinities to images of Odysseus, in his dress and also in his hairstyle, such as on the Penelope Painter’s cup. On the Lykaon Painter’s vase in Boston, Odysseus is shown in the gesture of contemplation, resting his head on his hand, as he converses with the shade of Elpinor in the underworld.23 But the writing tablet is out of place for Odysseus. We think of Odysseus as more of an ex tempore composer in Homer. Before the Phaiakians, Odysseus crafts his tales on a moment’s notice, without notes.24 Also, although Homer describes Odysseus as compact and strong and shorter than, for example, Agamemnon, he is not necessarily bad-looking, most of the time.25 The Met statuette’s large head with scruffy beard and fraught expression, and the slightly misshapen body, do not suit the entirety of Odysseus’s established iconography.

The statuette may represent another wordsmith, one who admired Odysseus and referred obliquely to him in his poetry: Hipponax, the sixth-century BC poet of contentious iambic verse and choliambic (“limping”) meters.26 Hipponax reputedly wrote acerbic attacks on Boupalos and Athenis, sculptors identified by Pliny as sons of Archermos of Chios. In Book 36 of the Natural History, Pliny claims that Boupalos and Athenis were Hipponax’s contemporaries and goes on to explain a rivalry between the poet and the sculptors: “The face of Hipponax was notoriously ugly; on account of this they impudently exhibited a humorous likeness of him to a circle of laughing spectators. In anger at this Hipponax unsheathed such bitter verses that some believe he drove them to the noose. This is untrue, since later they made several statues in neighboring islands” (Naturalis historia 36.4.11).27

The few surviving fragments of Hipponax’s poetry do not mention this particular statue, but his iambics are full of vituperative remarks about and condemnations of Boupalos. For example, according to Hipponax, Boupalos has “unnatural” relations with his mother.28 The sculptor is cast as well as the poet’s sexual rival.29 He is also his rival in art. In one fragment, Hipponax turns the tables and calls Boupalos a stone statue, a criticism that might suggest that Hipponax’s poetry is more powerful than Boupalos’s sculptural production.30

The Hellenistic and Roman biographical tradition about Hipponax is no doubt based on his self-descriptions, his fictitious accounts of his own exploits at the lowest levels of society, and his scurrilous comments about others in his poetry. As Enzo Degani and others have shown, the poet’s reputation for physical ugliness may reflect not only his slanderous comments about rivals but also self-parody.31 Metrodorus of Scepsis in the Art of Training notes that Hipponax “was not only small of body but also thin and yet was so muscular that in addition to other feats he threw even an empty oil flask a very great distance.”32 It is probable that in a lost verse of self-parody, Hipponax lets fly a lekythos instead of a discus, a scenario that recalls Odysseus’s great discus toss in Odyssey 8, a comparison Ralph Rosen has explored.33 In one poem Hipponax himself implies that he’s not a very large person: shivering and with chattering teeth, he prays to Hermes to provide him with “a cloak, a little tunic, little wooden-soled sandals, and little felt socks,” as well as sixty gold staters (emphasis added).34 In another poem he complains that Hermes never came through with either the warm clothes or the gold coins.35 Ultimately, Hipponax creates an unflattering self-portrait in poetry: he is small and wiry, poor, has thieving on the mind, hangs out with lowlifes and prostitutes, and hurls scatological invective and curses at his rivals. Then, in a poem that has not survived, he seems to have attributed a sculptured caricature to Boupalos, his archrival.36 By creating a fictitious self-portrait, a caricature, in poetry, Hipponax the poet is perhaps saying that he is a craftsman and takes on the role of a sculptor.

Sculptural caricature is not attested archaeologically in the sixth century BC, when Hipponax lived. The Hellenistic period presents another story. The figure characterized in the Metropolitan’s Hellenistic bronze is definitely short and wiry, his belly slightly distended by bad food or flatulence, and his demeanor is hunched and brooding. And, like Hipponax’s poetic persona, he lacks a cloak and shoes. The laborer’s simple exomis suits the lower-class image of his self-described roles, from thief to craftsman. His non-ideal body corresponds as well to the typical physique of the artisan who works indoors, a social outsider bent over his workman’s bench, described by Xenophon: “the illiberal arts (banausikai), as they are called, are spoken against, and are, naturally enough, held in utter disdain in our states. For they spoil the bodies of the workmen and the foremen, forcing them to sit still and live indoors, and in some cases spend the day at the fire.”37 Here Xenophon links artisanal work to low social class, just as Hipponax does, as well as to the ruin of the body. The statuette’s hunched, asymmetrical posture might even suggest that his gait was halting; in that case the bronze would literally incorporate the choliambic “limping” meters that Hipponax employed in his vituperative verses. If we restore a stick in his right hand, the concept of the limp would be emphasized further. The sculpture would personify not only the poet in his own words, but also the meter of his poetry.

The admiration for past poets was cultivated enthusiastically in the Hellenistic period, especially in Alexandria in the third century BC. During this period, scholars were actively recording and cataloguing works of Archaic and Classical Greek literature at the great Library of Alexandria. Many cults of poets were established or renewed at this time, and a number of posthumous and retrospective or imaginary portraits of poets were commissioned.38 Included in their number were statues of lyric poets, such as the “Old Singer,” now in Copenhagen, who is seated on a throne and richly draped.39 He appears to be entranced by the song he plays on the lyre he once held in his hands. At least three seated poets, all draped with himations, are included in a fragmentary Hellenistic sculpture group of philosophers and poets found at the Sarapieion at Memphis.40 Of the three, one holds a lyre and another a scroll. The third, unfortunately headless, statue may represent Homer. Better known is the retrospective portrait of Homer, of which over twenty copies survive, including a bust in Naples (fig. 15.10).41 He is shown as well dressed as the kings he sang about or for whom he is imagined to have performed.

There are exceptions to the rule that poets must be shown heroized and sumptuously draped: a number of scholars have suggested that the bronze portrait from the Villa dei Papiri, known as the Pseudo-Seneca, may be a copy of a retrospective/imaginary portrait of the epic poet Hesiod (fig. 15.11).42 The scraggly beard and weather-beaten skin evoke the caricatures of aged fishermen and peasants, preserved in great numbers in Hellenistic terracottas, but the passionate energy and compelling expression seem to ennoble this figure.43 Paul Zanker refers to “biographical physiognomy” here that might reflect “the life of toil, worry, and disappointment” that Hesiod describes in his verses.44 Such biographical portraiture is an obvious offshoot of the Bios-tradition, in which a poet’s oeuvre fed and colored the later accounts of his or her life and personality. This tradition was developed fully in the Hellenistic period and extended long into the Roman.45

Like the supposed Hesiod, the Metropolitan’s Hellenistic bronze statuette may be a retrospective and imaginary poet portrait in this vein. Here we have a figure whose physiognomy and dress are based on his self-described physical flaws, his imitation and parody of Odysseus, and his penchant for living life so close to the bone that he can afford neither shoes nor cloak: Hipponax. Even his wax tablet implies that as a poet he sticks with the tool for drafts and notes, a papyrus scroll being far out of his reach.46

One more characteristic of the statuette might further support the identification as Hipponax. In some aspects of pose and dress, the figure mirrors that of the Athenian cult statue of Hephaistos, discussed above. Hephaistos’s statue emphasizes the right side of the figure: his weight is on his right leg, his head turns to the right, and his exomis is fastened on the left shoulder so that his right arm could move freely. He is right-handed. All point to the “good” side of the Pythagorian Table of Opposites.47 The statuette, in contrast, has his weight on his left leg and his head turned to the left. His exomis is tied on his right shoulder and leaves the left arm free. His right hand either would have supported his head or held a stick. In one poetic fragment, Hipponax declares “I’m amphidexios [literally, I have two right hands], and I don’t miss with my punches.”48 The free left arm of the statuette might imply this ambidexterity. The emphasis on the left throughout the figure would suggest the darker side of the Pythagorian Table, and perhaps the negativity of Hipponax’s verses, as well as the poet’s presumed ugliness, both internal and external: the opposite of kalokagatheia.49

The sculptor also might have incorporated a visual pun in the inclusion of the diptych tucked into the figure’s belt: the word for “tablet” or “diptych” in Greek is ptykti or pychti, a feminine noun with the accent on the second syllable. It is close to the word for “boxer,” pychtis, a masculine noun with the accent on the first syllable. We are reminded that not only can the poet throw punches with both hands, he can write invective. His opponents don’t stand a chance as the effect of Hipponax’s words will last long after the sting of his punches has worn off.

The poetry of Hipponax enjoyed a considerable revival in the third century BC at Alexandria, where it was celebrated for the lasting power of its biting words.50 Pseudo-epigrams written for the tomb of Hipponax and preserved in the Palatine Anthology caution the traveler to beware his grave because any disturbance might have unwanted repercussions. For example, an epigram attributed to Philip of Thessaloniki warns: “Stranger, flee from the grave with its hailstorm of verses, the frightful grave of Hipponax, whose very ashes utter invective to vent his hatred of B[o]upalus, lest somehow you arouse the sleeping wasp who has not even now in Hades put to sleep his anger, he who shot forth his words straight to the mark in limping meters.”51

Like a wasp, Hipponax’s ability to sting lasts long after his death. This idea puts a spin on the concept of the relative immortality of poetry when compared to that of built monuments at the heart of the paragone—the competition between the poetry and the visual arts—that Pindar and Simonides, among others, promoted and that Hipponax embodied in his ongoing feud with the sculptor Boupalos.52

Hipponax was revived most effectively by Kallimachos, the first librarian at Alexandria, himself a poet. Emulating Hipponax, Kallimachos wrote a book of thirteen iambic poems. In the very first line of Iambos 1, Kallimachos imagines Hipponax returning from Hades itself, to gather together a group of Alexandrian literati in order to advise them against envying one another. “Listen to Hipponax,” he says, “for it is I in fact who have come from the place where they sell an ox for a penny, bearing iambics that do not sing of the fight with Bupalus….”53 A few lines later in the same poem, as the scholars arrive in droves, Hipponax describes himself as “the bald man” not willing to set aside a “threadbare cloak” (i.e., not spoiling for a fight), but to tell, instead, the story of the Seven Sages.54

In Iambos 1, Kallimachos underscores Hipponax’s unattractive looks, his poverty, his feud with Boupalos, and the subject of one of his poems, as Hipponax is one of the earliest Greek poets to mention the tale of the Seven Sages.55 He also employs the iambic and choliambic meter that Hipponax claimed to have invented, all in the self-referential way that Hipponax employed them.56 But the meter that was acknowledged by ancient grammarians to be best suited to angry and curse-filled verses appears to be used by Kallimachos instead to elevate and rehabilitate Hipponax.

Kallimachos’s ennobling of the poet does not come out of the blue, however. M. L. West has noted that despite its invective subject matter, the poems of Hipponax are cleverly and beautifully constructed.57 The poet, he argues, far from being a lowlife of the sort he describes in his verses, is as artful as the noblest of lyricists. Like West, Kallimachos saw in Hipponax the high quality of his poetry and not just the work of a “vulgar simpleton.”58 Kallimachos’s rehabilitation and literal resurrection of Hipponax in Iambos 1, in which the poet chastises other writers for quarreling among themselves and admonishes them to “rise above,” raises Hipponax and puts him on a level with other early poets, such as Archilochos, who wrote lyric as well as invective. The artist of the bronze statuette appears to think along the lines of Kallimachos. He shows us, as do most sculptors of retrospective and imaginary portraits, a portrait inspired by his subject Hipponax’s poetry: the poet is short and wiry, balding, cloakless, and crabby, and with a limp like his choliambic verses. But with the intense gaze and silver eyes he also shows the noble qualities of the poet who wrote, in West’s words, “simple but potent” lines that have “the clear-cut quality of the best Greek poetry,” the “artless art” of the finest lyricists.59 In a word, Kallimachos “got” Hipponax. The statuette’s sculptor “got” Hipponax too. Both understood the poet at the heart of the poetry.

Hipponax’s revival in Alexandria by Kallimachos in the third century BC, and his appreciation by Hellenistic poets, scholars, and erudite patrons in the hothouse atmosphere provided by the Great Library itself, may have inspired the imaginative portrait seen in the statuette: a figure who, although imperfect in form, is strong, with a thoughtful countenance; whose extraordinary intellectual and creative powers shine through silver eyes, and with a wax tablet to record those extraordinary thoughts. In combining an artisan’s body with a poet’s means of expression, an actual Hellenistic sculptor refigured in the bronze statuette of Hipponax a personification of the struggle between the poet and his archnemesis, the sculptor Boupalos, revealing the paragone between poetry and the visual arts at the heart of Hipponax’s poetry. The statue is reputed to have come from the sea off North Africa, which might suggest Alexandria as its place of manufacture. Wherever this statuette stood originally, many must have sought inspiration from it, for the bald forehead has been worn and rubbed smooth by touch, no doubt by those who sought luck and inspiration, or even protection, from the poet’s aura.60

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Kenneth Lapatin and Jens Daehner for the invitation to contribute a paper to the XIXth International Congress on Ancient Bronzes. Thanks are due as well to Gianfranco Adornato, Ruth Bielfeldt, Kenneth Lapatin, and John Pollini for valuable questions and discussion of the paper. I am most indebted to Guy Hedreen, whose chapter on Hipponax in The Image of the Artist in Archaic and Classical Greece: Art, Poetry, and Subjectivity (2016) introduced me to the biographical tradition surrounding the poet, and for selflessly standing as sounding board for many of the ideas presented here. For photographs, thanks are due to Maria Chidiroglou at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens; Liz Kurtulik Mercuri at Art Resource; Craig Mauzy at the Athenian Agora; Dr. Ramona Messerig, Dr. Ellen Riemer, and Ursula Rudischer at the Landesmuseum Mainz; and Marie-Lan Nguyen of Wikimedia Commons. The photographs of the “Bronze Artisan” himself are from the Metropolitan Museum Collections website and are used here thanks to OASC at www.metmuseum.org.

Notes

- New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, inv. 1972.11.1. Hemingway 2015, 262–63, no. 36 with bibliography; and Hemingway 2016, cat. 71. On the findspot: Himmelmann 1981, 205. ↩

- Himmelmann 1983, 78. ↩

- Some of the figure’s disproportionate physical properties possibly reflect a congenital syndrome known as spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. For the syndrome, see Dasen 1993, 8–15. ↩

- Lee 2015, 112 with nn. 178–81. A variety of figures wear the exomis: a Hellenistic or Roman bronze figurine of a fisherman from Volubilis (Musée archéologique de Rabat inv. 99.1.12.1345): Morel-Deledalle 2014, 154–55; the Hellenistic Jockey from Artemision (Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. X15177): Hemingway 2004, 44, fig. 25, 55; a bronze shepherd statuette from Ampelokepoi (Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. X16789): Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 106, fig. 7.8; the dancing male dwarf from the Mahdia shipwreck (Tunis, Musée National du Bardo, inv. F215): Picón and Hemingway 2016, 289, inv. 233 with figure; Pfisterer-Haas 1994, 484–86 with figs. 6, 7, 13–15, and color plate 17. Two first-century BC small terracotta figures of bald, thin, stooped, exomis-wearing comic actors in the guise of slaves from Myrina, in the Athens National Archaeological Museum (inv. 5050 and 5051), await publication. ↩

- Himmelmann 1981, 205 and 1983, 76. ↩

- Hemingway 2015, 262. ↩

- Boucher-Colozier 1965, 38. ↩

- Himmelmann 1983, 76–85; Török 1995, 116–18, nos. 156–57, plates XIII, LXXXII–LXXXIII. ↩

- Himmelmann 1983, 79 and plate 59a. ↩

- Himmelmann 1983, 78. ↩

- Hemingway 2015, 262. For Hephaistos’s limp, see Iliad 18.371 where he’s described as “club-footed” (kyllopodiōn) and Iliad 18.397 where the god describes himself as “lame” or “crippled” (chōlon). On Hephaistos’s lameness: Hedreen 2016, 137–38. ↩

- Frel 1981, 17; Hemingway 2015, 262. ↩

- Harrison 1977, 140, illustration 2; 146–48. ↩

- Agora L 5413: Harrison 1977, 147, fig. 4; and Athens National Archaeological Museum, inv 18011-2, Empedokles Collection: Harrison 1977, 147, fig 3. ↩

- Brommer 1973, 6, cat. 18 and plate 18. Reflections of the Hephaisteion statue appear in Greece as early as the fourth century BC, for example on a grave relief, Worcester Art Museum, inv. 1936.21, CAT 1.153. Roman images of Vulcan in this pose may begin as early as the first century BC as seen on the base with Vulcan, Venus, and Amor from Falerii (Cività Castellona). See Kuttner 1995, 39 and fig. 28. ↩

- On the pilos as the craftsman’s hat, see Pipili 2000, 153–62. ↩

- Pompeii VI 15.1, Casa dei Vettii, triclinium P, North Wall: LIMC 7.2, plate 130, Pasiphaë 11. See also De Carolis 2001, 56 and illustration on 57; and Panetta 2004, 365. ↩

- The triclinium mosaic in the so-called House of Poseidon shows Pasiphaë commissioning the artificial cow from Daidalos, who shrinks from the task: Abadie-Reynal 2002, 751–52 and fig. 6. LIMC Supplementum 2 2009, pl. 71, Daidalos et Ikaros, add. 5. ↩

- Marble sarcophagus: Paris, Louvre, inv. MA 1033. LIMC 7.2, plate 131, Pasiphaë 23. See also Maurer 2015, 208–11 with fig. 6.4. Himmelman 1981, 205, notes a similarity of dress and gesture between the bronze artisan and the image of Daidalos at the far left on the sarcophagus. ↩

- Second-century AD marble relief (rosso antico) from Rome. Villa Albani inv. 164. LIMC 3.1, 317, Daidalos et Ikaros 23a; LIMC 3.2, pl. 239, Daidalos et Ikaros 23a. Neudecker 1992, 125–27. A second relief in the Villa Albani, inv. 1009, is largely restored, based on inv. 164. See LIMC 3.1, 317, Daidalos et Ikaros 23b. ↩

- For example, an Etruscan bronze mirror case of the third century BC shows Odysseus talking to Penelope: London, British Museum, inv. 1865, 0712.8; Gaultier and LaCroix 2013, 51, 305 (cat. 378). ↩

- LIMC 6.1, 956, Odysseus 87. LIMC 6.2, pl. 627, Odysseus 87. ↩

- Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 34.79: Lykaon Painter, red-figure pelike, ARV2 1045.2, 1679; Paralipomena 444; BAPD 213553; LIMC VI.2, pl. 632, Odysseus 149. ↩

- Odyssey 9–12 for Odysseus’s story. ↩

- On Odysseus’s good but somewhat different looks see, for example, Iliad 3.192–96; Odyssey 8.134–36. Athena also occasionally adds to Odysseus’s charisma and accentuates his good points: Odyssey 6.229–35; 8.18–20; 23.156–63. His normally handsome presentation is disrupted when Athena intentionally disguises him with attributes of an old beggar: Odyssey 13.429–38. ↩

- An original Hellenistic portrait head of a bearded man with a fillet discovered in the Kerameikos (Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. 2800) has been called “Hipponax” because of his grim expression. No further evidence supports the identification. See Zanker 1995, 154, 369, n. 7; and 155, fig. 82; Dillon 2006, 86, 124 and fig. 126. ↩

- Pliny Naturalis historia 36.4.11 = Hipponax test. 1W; Gerber 1999, 342–43. ↩

- Frag. 12W, metrokoites, literally “mother-fucker” (Gerber 1999, 362–63), and possibly frag. 70W, 7–8 (Gerber 1999, 404–405). For Hipponax’s rivalry with Boupalos, see Hedreen 2016, 106–10. ↩

- For example, frag. 15W, Gerber 1999, 354–55. ↩

- On the rivalry between Hipponax and Boupalos as an early iteration of the paragone between poetry and the visual arts: Hedreen 2016, 103, 115–16. ↩

- West 1974, 28–30, 32–33; Degani 2002, 150–51. ↩

- Athenaeus 12.552c–d = test. 5W; Gerber 1999, 346–47. ↩

- Gerber 1999, 347, n. 3. Rosen 1990, 11–15, discusses the scene between Euryalus and Odysseus in Odyssey 8.158–90. See also Hedreen 2016, 103–7, for Hipponax’s relationship to Odysseus. ↩

- Frag. 32W, Gerber 1999, 376–77. ↩

- Frag. 34W, Gerber 1999, 380–81. ↩

- Hedreen 2016, 110–16. ↩

- Xenophon Oikonomikos 4.2–3, text/trans. Marchant and Todd 1923. ↩

- On cults of poets, see Zanker 1995, 158–73; Clay 2004, especially 127–51; Dillon 2006, 105–6. Some poet’s cults had been founded as early as the fifth century BC, hence Artistotle’s citation of Akidamas’s observation that “Everyone honors the wise. The Parians honored Archilochos, even though he was a slanderer [blásphemos] and the Chians have honored Homer although he was not one of their citizens….” Rhetorica 2.23.1398 b 11–12. Trans. Lefkowitz 2012, 32. ↩

- “Old Singer”: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. 1563; Zanker 1995, 146–49 and 148–49, figs. 79a–b, and Clay 2004, 61 with pl. 30. ↩

- Bergmann 2007, 247–56, figs. 161–64, 166–67. ↩

- Richter and Smith 1984, 147, 150; Zanker 1995, 168–71, with fig. 90. ↩

- Richter and Smith 1984, 191–92. Identification as Hesiod: Pollitt 1986, 119–20; Smith 1991, 37; Zanker 1995, 151–54, and 369, n. 4, where the author states, “Most archaeologists are currently inclined to the identification as Hesiod.” ↩

- For Hellenistic images and figurines of fishermen and peasants, see, for example, Himmelmann 1983, 26, plates 31a–b, 33a–b. More recently, Masséglia 2015, 219–41. Examples from Myrina (“personnages comiques”): Mollard-Besques 1963, 346 and pls. 174b, 175b, 175f. ↩

- Zanker 1995, 151. ↩

- Lefkowitz 2012; Bing 1993, 619–31. ↩

- Meyer 2009 argues that Muses are often shown with diptychs in Greek and Roman art, and poets with scrolls. In a Pompeian wall-painting (House of the Golden Bracelet, VI Ins. Occ. 17.42), a muse hands a poet a wax tablet, a gesture that indicates that the wax tablet was used for inspired ideas before the final draft: Meyer 2009, 581, fig. 12. ↩

- Aristotle Metaphisica 1.5.986a. Vidal-Naquet 1986, 61–82, presents a classic study of the Pythagorean oppositions. See especially 64–65. ↩

- Frag. 121W, Gerber 1999, 423. ↩

- Hipponax’s poetry is the opposite of the praise poetry that one associates with athletic victory or positive civic duty. Accordingly, his portrait lacks the harmonious proportions one associates with the ideal commemorative sculpture. For example, the disproportionate size of the artisan’s head when compared to his body would underscore the lack of commensurability of parts one associates with idealized athletic figures, such as the Polykleitan types where the parts of the body are proportioned harmoniously with one another. Lissarrague 2000, 136, discusses Aesop as the opposite of an ideal figure, in that he is characterized by some ancient sources as a barbarian and a slave as well as ugly and deformed. The bronze artisan has some similar attributes to this description, but does not reflect all of the extremities that are said to characterize Aesop. ↩

- Kerkhecker 1999, 7, notes that “early in the third century, Hipponax is fashionable. After a period of almost complete obscurity, there is a sudden burst of Hipponactean verse, a choliambic craze. Callimachus is reacting, not only to the past but to the present.” ↩

- Anthologia Palatina 7.405, test. 8W, Gerber 1999, 348–49, trans. Gerber. ↩

- Hedreen 2016, 115–16. ↩

- Kallimachos, Iambi 1, ll. 1–4, trans. Gerber 1999, 347, test. 6W. ↩

- Kallimachos, Iambi 1, ll. 29 and 30, respectively: Trypanis 1978, 106–7. Trypanis idem., n. c, notes that one scholiast suggests that the temple site where Hipponax tells the literati to gather is the Sarapieion at Alexandria. The idea of gathering great thinkers and writers at a Sarapieion may have inspired, or been inspired by, the actual sculpture group of poets and philosophers at the Sarapieion at Memphis. For the sculpture group see Bergmann 2007. ↩

- Strabo 14.1.2 = test. 123W, Gerber 1999, 454–55. ↩

- Hedreen 2016, 101–3; Acosta-Hughes 2002, 36–38. ↩

- West 1974, 28–29. ↩

- West 1974, 28. ↩

- West 1974, 28–29. ↩

- The square knot on the statuette’s right shoulder and the other that ties his belt might be seen as apotropaic in function. A pseudo-epigram by Theokritos for the tomb of Hipponax also suggests that although scoundrels should give Hipponax’s tomb wide berth, those who are honest have nothing to fear—and can even nap on the tomb. Thus, Hipponax might protect the good-hearted. Theocritus, Epigrammata 19 Gow = HE 3430–33 (Anthologia Palatina 13.3), test. 7W; Gerber 1999, 346–47. ↩

Bibliography

- Abadie-Reynal 2002

- Abadie-Reynal, C. 2002. “Les maisons aux décors mosaïqués de Zeugma.” CRAI 146.2: 743–71.

- Acosta-Hughes 2002

- Acosta-Hughes, B. 2002. Polyeideia: The Iambi of Callimachus and the Archaic Iambic Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bergmann 2007

- Bergmann, M. 2007. “The Philosophers and Poets in the Sarapieion at Memphis.” In Early Hellenistic Portraiture: Image, Style, Context, ed. P. Schulz and R. von den Hoff, 246–63. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bing 1993

- Bing, P. 1993. “The Bios-Tradition and Poets’ Lives in Hellenistic Poetry.” In Nomodeiktes: Greek Studies in Honor of Martin Oswald, ed. R. M. Rosen and J. Farrell, 619–31. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Boucher-Colozier 1965

- Boucher-Colozier, Stéphanie. 1965. “Un bronze d’époque Alexandrine: Réalisme et Caricature.” Monuments et mémoires (Fondation Eugène Piot) 54: 25–38.

- Brommer 1973

- Brommer, F. 1973. Der Gott Vulkan auf provinzialrömischen Reliefs. Cologne and Vienna: Böhlau.

- Brown 1997

- Brown, C. G. 1997. s.v. “Iambos.” In A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets, ed. D. E. Gerber. Leiden, New York, and Cologne: Brill.

- Clay 2004

- Clay, D. 2004. Archilochos Heros: The Cult of Poets in the Greek Polis. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

- Daehner and Lapatin 2015

- Daehner, J. M., and K. Lapatin, eds. 2015. Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Dasen 1993

- Dasen, V. 1993. Dwarfs in Ancient Egypt and Greece. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- De Carolis 2001

- De Carolis, E. 2001. Gods and Heroes in Pompeii. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Degani 1991

- Degani, E. 1991. Hipponax: Testimonia et Fragmenta. Stuttgart and Leipzig: B. G. Teubner.

- Degani 2002

- Degani, E. 2002. Studi su Ipponatte: Nuova edizione anastaticamente riprodotta. Hildesheim: Georg Oms.

- Dillon, S. 2006

- Dillon, S. 2006. Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Styles. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Frel 1981

- Frel, J. 1981. Greek Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Gaultier and LaCroix 2013

- Gaultier, F., and M. LaCroix 2013. Les Etrusques et la Méditerranée: La cité de Cerveteri. Paris: Louvre Museum.

- Gerber 1999

- Gerber, D. E. 1999. Greek Iambic Poetry. Cambridge (MA).: Harvard University Press.

- Harrison 1977

- Harrison, E. B. 1977. “Alkamenes’ Sculptures for the Hephaisteion: Part 1, The Cult Statues.” AJA 81: 137–78.

- Hedreen 2016

- Hedreen, G. M. 2016. The Image of the Artist in Archaic and Classical Greece: Art, Poetry, and Subjectivity. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hemingway 2004

- Hemingway, S. 2004. The Horse and Jockey from Artemision: A Bronze Equestrian Monument of the Hellenistic Period. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Hemingway 2015

- Hemingway, S. 2015. “Statuette of an Artisan.” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 262–63.

- Hemingway 2016

- Hemingway, S. 2016. “Statuette of an Artisan.” In Picón and Hemingway 2016, 161–62.

- Himmelmann 1981

- Himmelmann, N. 1981. “Realistic Art in Alexandria.” Proceedings of the British Academy 67: 194–207.

- Himmelmann 1983

- Himmelmann, N. 1983. Alexandria und der Realismus in der griechischen Kunst. Tübingen: E. Wasmuth.

- Kerkhecker 1999

- Kerkhecker, A. 1999. Callimachus’ Book of Iambi. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Kuttner 1995

- Kuttner, A. L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lee 2015

- Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lefkowitz 2012

- Lefkowitz, M. R. 2012. The Lives of the Greek Poets. 2nd ed. London: Bristol Classical Press.

- Lissarrague 2000

- Lissarrague, F. 2000. “Aesop, Between Man and Beast: Ancient Portraits and Illustrations.” In Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, ed. Beth Cohen, 132–49. Leiden and Boston, Cologne: Brill.

- Marchant and Todd 1923

- Marchant, E. C., and O. J. Todd, trans. 1923. Xenophon. Vol. 4: Memorabilia, Oeconomicus, Symposium, Apology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Masséglia 2015

- Masséglia, J. 2015. Body Language in Hellenistic Art and Society. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mattusch 1980

- Mattusch, C. C. 1980. “The Berlin Foundry Cup: The Casting of Greek Bronze Statuary in the Early Fifth Century B.C.” AJA 84: 435–44.

- Maurer 2015

- Maurer, M. F. 2015. “The Trouble with Pasiphaë: Engendering Myth in the Gonzaga Court.” In Receptions of Antiquity, Constructions of Gender in European Art, 1300–1600, ed. M. Rose and A. C. Poe, 199–229. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Meyer 2009

- Meyer, E. A. 2009. “Writing Paraphernalia, Tablets, and Muses in Campanian Wall Painting.” AJA 113: 569–97.

- Mollard-Besques 1963

- Mollard-Besques, S. 1963. Musée du Louvre: Département des antiquités grecques et romaines: Catalogue raisonné des figurines et reliefs en terre-cuite grecs, étrusques, et romans. Vol. 2: Myrina. Paris: Editions des Musées nationaux.

- Morel-Deledalle 2014

- Morel-Deledalle, M., ed. 2014. Splendeurs de Volubilis: Bronzes antiques du Maroc et de Méditerranée. Exh. cat. Marseilles, Le musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée (MuCEM). Arles: Actes Sud.

- Neudecker 1992

- Neudecker, R. 1992. “Relief mit Daidalos und Ikaros.” In Forschungen zur Villa Albani: Katalog der antiken Bildwerke. Vol. 3, 125–27, no. 296, plate 84. P. C. Bol, ed. Berlin: Gebr. Mann.

- Panetta 2004

- Panetta, M. R., ed. 2004. Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City. Vercelli: White Star.

- Pfisterer-Haas 1994

- Pfisterer-Haas, S. 1994. “Die bronzenen Zwergentänzer.” In Das Wrack: Der antike Schiffsfund von Mahdia, ed. G. Hellenkemper Salies, H-H. von Prittwitz und Gaffron, and G. Bauchhenß, vol. 1, 483–504. Cologne: Rheinland-Verlag GmbH.

- Picón and Hemingway 2016

- Picón, C. A., and S. Hemingway. 2016. Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Pipili 2000

- Pipili, M. 2000. “Wearing the Other Hat: Workmen in Town and Country.” In Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, ed. B. Cohen, 153–79. Leiden, Boston, and Cologne: Brill.

- Pollitt 1986

- Pollitt, J. J. 1986. Art in the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Richter and Smith 1984

- Richter, G. M. A., and R. R. R. Smith. 1984. The Portraits of the Greeks, rev. ed. Oxford: Phaidon.

- Rosen 1990

- Rosen, R. M. 1990. “Hipponax and the Homeric Odysseus.” Eikasmos 1: 11–25.

- Smith 1991

- Smith, R. R. R. Hellenistic Sculpture. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Török 1995

- Török, L. 1995. Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Trypanis 1978

- Trypanis, C. A., ed. 1978. Callimachus: Aetia, Iambi, Hecale and Other Fragments. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- West 1974

- West, M. L. 1974. Studies in Greek Elegy and Iambus. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Vidal-Naquet 1986

- Vidal-Naquet, P. 1986. The Black Hunter: Forms of Thought and Forms of Society in the Greek World. Trans. A. Szegedy-Maszak. Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press.

- Zanker 1995

- Zanker, P. 1995. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. Trans. Alan Shapiro. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and Oxford: University of California Press.