8. When a Statue Is Not a Statue

- Carol C. Mattusch, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia

Abstract

A number of large-scale bronzes that have been identified by scholars as being Archaic, Classical, or Hellenistic statues of kouroi, mellephebes, a very young Apollo, or Dionysos may need to be reclassified. Many of them are now assigned to the Hellenistic or Graeco-Roman period, the explanation being that wealthy Romans continued to enjoy earlier styles of statuary. Other evidence suggests a different interpretation. At least three of these figures originally recognized simply as statues were found together with fragments that were identified after reconstruction as elaborate supports for trays. At least one wall-painting depicts such a tray-bearer on a base in a triclinium, and literary testimonia also refer to such figures. Two of the figures previously identified as statues were in fact discovered in triclinia. So in what sense are they statues? One by one, these bronzes are being added to an ever-expanding genre of what might better be described as luxury furniture—tray-bearers and lamp-holders. It appears to be a genre that was very popular in wealthy homes of the Graeco-Roman world. Interestingly enough, no marble examples of this type have as yet been identified, and so far none of the bronzes can be securely dated before the Hellenistic period.

Why have we been so slow to recognize this class of ancient bronzes? Is it because we might have to describe them not as statuary bronzes belonging to the major arts, but rather as interior decor, as a minor art, or—perhaps somewhat easier on our own aesthetic perceptions—as luxury art? Will familiar works like the Apollo from Piombino and Apollo the Citharist from Pompeii no longer shape our modern aesthetic? Is it possible that even statues such as the Marathon Boy will be moved from future discussions of Classical sculpture into the category of luxury arts? A new and expanded view of the luxury arts may well change our comprehension of ancient art.

The Piombino Apollo has recently undergone new studies of its production, measurements, alloy, and associated inscriptions (fig. 8.1, left). That statue and the similar Apollo from Pompeii (fig. 8.1, right) were installed side by side for the first time in the exhibition Power and Pathos, which made it possible to compare and contrast the two figures and to raise new questions about their similarities and differences. The Piombino Apollo was discovered underwater and sold at Livorno in 1832; in 1834 it was acquired by the Louvre.1 On the statue’s left foot, in capital letters, the phrase “… ος Αθαναια δεκαταν” (… os dedicated this as a tithe to Athena) was cut in the metal after casting2 and inlaid with silver. The image’s peculiar style led to debate over its date that continued until 1967, when Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway argued persuasively that the Piombino Apollo was made in the Late Hellenistic period.3 Inside the statue were four fragments of a lead tablet, three of which were exhibited in Power and Pathos. The lead strips are inscribed with another phrase, in handwriting similar to that on the foot, partially preserving the names of its sculptors: “… ηνοδο … φων Ροδ[ι]ος εποo …” ([M]enodotos and … phon of Rhodes made it).

Menodotos of Tyre founded a workshop in Rhodes, for which three generations of his family are recorded, ranging in date from 150 BC to perhaps 50 BC, and two of his descendants also bore the name Menodotos.4 These dates have suggested to some that the bronze image from Piombino might have been dedicated to Athena Lindia in Rhodes during the last quarter of the second century BC, and that it was shipped to Italy at some later date.5 Sophie Descamps-Lequime has asked, however, whether a statue of a god could be dedicated to another god,6 and this leads to the question of whether this kouros necessarily represents Apollo. That is, in what sense might an archaizing kouros be recognized as a statue of that god and yet actually have been dedicated to Athena. One might even ask whether the statue’s buyer believed that this was an Archaic statue, as did many modern scholars. Furthermore, the bronze from Piombino may not have been produced in Rhodes. Menodotos himself came from Tyre, and inscriptions record works by his family members in Halikarnassos, in Athens, and in Delphi. A versatile family, they produced at least three different types of works: an athletic group, portrait statues, and the archaizing Piombino bronze.7 This image is of very high quality, with delicate detailing of the hair, gracefully curving inlaid copper brows and lips, inlaid copper nipples, and almost no evidence of bubbles, patches, or other repairs, beyond the possible repair of one toe.8

In 1978, excavation at Pompeii in the House of Gaius Julius Polybius (IX 13.1–3) uncovered in the triclinium identified as EE a bronze image bearing remarkable similarities to the Piombino (see fig. 8.1, right).9 This bronze, however, is also said to have been standing on a small, round molded base. Seeing the two bronzes exhibited side by side has led to a number of new general observations, although detailed comparisons are hampered by the fact that no systematic study of the Pompeii bronze has yet been undertaken. Nonetheless, new measurements have been made of both statues at the same points and with the same instruments.10 The most important difference between the two is that the Pompeii bronze is significantly taller (by about 12.5 cm, or just over 5 in.) than the Piombino. This discrepancy in height may be explained by the fact that joining limbs to bodies or heads to necks can easily affect measurements as well as overall configuration. Furthermore, in twenty-eight of thirty-six measurements taken of the two, the Pompeii bronze is between 1 millimeter and 5.6 centimeters (up to 2 ½ in.) larger than the Piombino; it is 1 to 9 millimeters (up to ⅜ in.) smaller at five points; and the two bronzes are equal in only three measurements.11

The two statues are, however, of precisely the same Hellenistic type: they are archaizing kouroi with the left foot slightly forward; and both have highly decorative features. In addition, the profiles of the two bronzes strongly suggest that they are based on the same basic model or on two versions of that basic model, which would account for the differences: the Pompeii statue’s neck is thicker and more cylindrical, and the torso is bulkier, whereas those features on the Piombino are more delicately modeled; the right buttock of the Pompeii bronze is farther back than the left one, and the Piombino’s buttocks are aligned, but his feet are farther apart than those of the Pompeii bronze.

There are many differences in surface details, such as in the rendering of the hair and facial features. The bronze from Pompeii has wavy locks, each finely combed, radiating from the crown of his head; there are rows of snail-shell curls and spiral locks on his forehead; his long hair is knotted at the back of the neck in a broad bun; he wears a diadem and a tiara ornamented with upright lotuses and palmettes; and the two neatly arranged fillets emerging from behind his ears are neatly splayed across either side of his chest. The Piombino bronze has wavy, finely combed hair radiating from the crown of his head, a row of roughly delineated curlicue locks on his forehead, parts of a diadem visible behind the ears with wavy locks folded symmetrically over it, and the longer hair beneath that is tied in a four-part knot at the nape of the neck.

Many and perhaps all of the individualizing features were added on the wax working-models, resulting in different editions of the same basic model for an archaizing youth. If so, why are the measurements so different? And why is the Piombino bronze a nearly flawless casting, whereas there are many small rectangular patches on the Pompeii bronze recording the repair of casting flaws?

At this point, all we can say for certain is that the similarities between the two bronzes cannot be coincidental. There was surely a basic model for this particular kouros, and copies of that model, as of any popular type, would have been owned by more than one workshop. If so, such bronzes might have been commissioned in different times and at different places, the Piombino between approximately 150 BC and 50 BC, perhaps on Rhodes or perhaps not, and the other in Pompeii at some date before AD 79. At the same time, because each bronze was carefully individualized in the wax, each of them is undoubtedly one of a kind, representing a different edition of the basic model. They are both more decorative than pious.

The Piombino is likely to have been conceived and recognized as an archaistic statue, given its significant departures from Archaic standards, particularly in the hairstyle. But it poses a number of questions. Was it dedicated to Athena, or was the inscription cut on top of the foot a form of artifice, like the style of the statue? Why were the names of the artisans hidden on a lead tablet inside the statue? And does the slightly flattened left forearm reveal that the wax model was made to support a tray?

The Pompeii bronze is usually described as probably having once held a phiale and a bow, the floral tray-supports that he was holding at the time of discovery being identified tentatively as a sign of later adaptation for use in the triclinium in which the image was found.12 There is a hole in the statue’s right palm, beside which is marked “III”; another mark cut on the back of the attachment for one of the floral supports appears to read “VIII” or “III.”13 Did these numbers guide the assembly, ensuring that workmen chose attachments that would fit the statues? There are no signs of solder having been used to fix the attachments in place. To those scholars who would prefer to think that this image started its existence as a statue, it is possible that when the image was not in use as a server, the tray or lamp could have been replaced by other fittings, such as a phiale and a bow. Thus the tray-holder would become a statue, the tray could be cleaned, a pitcher polished, a lamp refilled with oil. Perhaps this Graeco-Roman archaistic statue-type had been created to serve a dual function, as a statue and as a tray-holder, the attributes changed as the situation demanded. The highly decorative details of both bronzes suggest that they were made as fine furnishings that took the form of Archaic statues, a style that never fell from favor.

Evidence of such furnishings can be found in literary sources. Entering the palace of the Phaiakian king Alkinoos, Odysseus crosses a bronze threshold; there are silver columns and lintel, golden doors with a golden handle, and gold and silver guard-dogs. Where the Phaiakians gathered for the evening’s entertainment, “there were golden youths (χρύςειοι κοῡροι), holding in their hands blazing torches, and standing on the strong-compounded bases, to shed a gleam through the house by night, and to shine on the banqueters” (Homer Odyssey 7.100–102).14 Lucretius, who preferred natural pleasures, disdainfully recalled these Homeric lines, scoffing at the “golden images around the house of youths (aurea simulacra) holding flaming torches in their right hands to light banquets that last into the night” (De rerum natura 2.24–26).15

There are, in fact, numerous statues that are known today as silent butlers, a designation that might have inspired Lucretius to further criticism. They are all bronzes, all ephebes, and they range broadly through archaizing and classicizing styles, many of them standing on small round bases. Like real children, they are all diminutive in size. Their extended or raised hands, now devoid of their detachable accessories, have given rise to lively and continuing debate about their identity. I will examine these in turn, including one depicted in a wall-painting.

The Citharist

In October of 1853, the clearing of a street in Pompeii was interrupted by a mudslide that exposed a large house (I 4.1–3), which was actually two houses joined together, with entrances on both the Via Stabiana and the Via dell’Abbondanza. In early November of the same year, the diggers found a bronze statue of a youth16 in what was later identified as the southeast corner of the south peristyle courtyard, adjacent to a large triclinium (fig. 8.2). Excavations in the house were halted for five years; when they began again in 1858, the House of the Citharist was given its name, deriving from the identification of the statue as an Apollo who had once held a cithara.17

The male figure, an ephebe early Classical in style, stands on a molded bronze base that is just large enough for his feet. He has long hair divided into finely striated (as if combed) wavy locks radiating from the crown of his head, parted in the middle of the forehead, and rolled around a diadem. There are delicate comma-like curls on the back of the neck, and two long, thick, curly locks escape from behind each ear and fall to the shoulder blades.18 The boy’s eyes are inset in bone or ivory and stone; the nipples are inlaid with copper. He looks down in the general direction of his raised left hand, into the palm of which is fitted a rectangular plaque with two curious features: half of an elongated oval on one side; and something that resembles a keyhole beside it, perhaps a notch. In the lowered right hand, he holds a thick, curved object that is slightly longer than the width of his hand: it is rounded, curving, and tapered toward the back, with hollows on either side of the thicker end. That object has always been identified as a plectrum, the rectangle in the other palm as the vertical arm of a cithara, and the youth himself as a prepubescent Apollo.

The lyre and the cithara both have arms that rise from the sides of the instrument’s body, the strings attached to a crossbar at the top. The cithara is larger than the lyre; a tortoiseshell may form the back of a lyre. Both instruments are associated with Apollo, and both were plucked with the fingers or with a plectrum,19 a small, flat piece of shell, horn, or metal that does not resemble the thick object that this statue is holding in his right hand. The rectangular object in the left hand has not yet been identified.

The Ephebe

Seventy-five years after the Citharist was found, in 1925, less than two blocks away on the Via dell’Abbondanza, Amedeo Maiuri excavated a very large home (I 7.11) consisting of several conjoined houses with three entrances. Another small bronze youth was excavated there; it became known as the Ephebe from the Via dell’Abbondanza,20 and the house was soon named the House of the Ephebe (fig. 8.3). The statue was found at the entrance to a hallway connecting an atrium and a tablinum, where it and other objects were thought to have been in storage during a renovation project.

Like the previous image, this bronze is slightly under 150 centimeters (59 in.) in height. He too stands on a small, round molded-bronze base, this one mounted on a round marble footed base. In his left hand he held a floral support for a tray. This ephebe has essentially the same hairstyle as the one found nearby, even the little comma-like curls on the back of his neck, lacking only the long spiral sidelocks. The similarities between the two boys—in size, in identity, in early classicizing design, in their small, round bases—could well mean that they were both products of the same Pompeiian workshop. Was the “citharist” also a tray- or lamp-bearer? Had his tray been temporarily removed, allowing him to function as a statue? It would be no surprise to find similar rich furnishings in two fine houses located only two blocks apart on the same street. Scholars might wish to consider what else these two bronzes have in common. Were they made in the same way? Do their arms and legs and heads have comparable measurements? Is the copper alloy similar?

The Youth from the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus

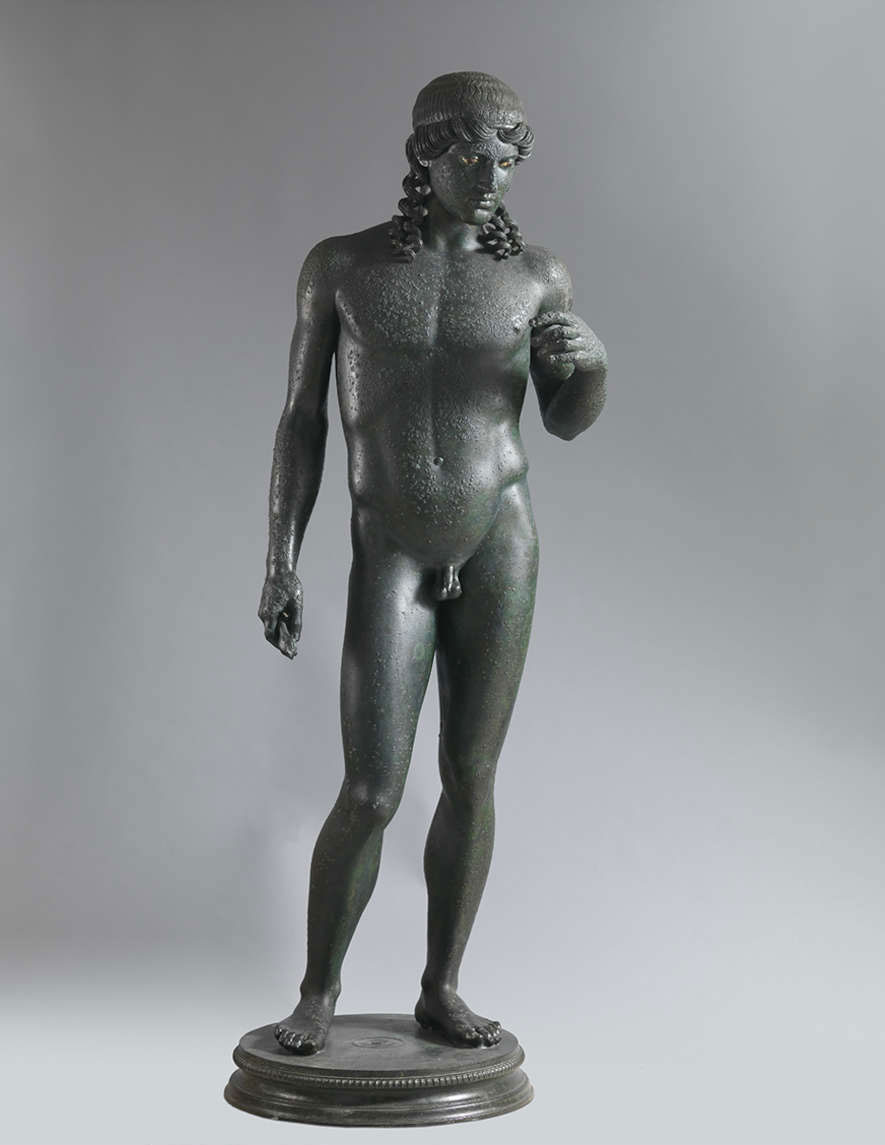

In 1960, a fleshy bronze youth, Late Classical in style, poised gracefully on an elaborate base, was excavated at Pompeii, in the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus, the location unspecified (fig. 8.4).21 The height of the statue on its base is 137 or 139 centimeters (ca. 54 in.), of the figure alone 122 centimeters (48 in.). He has long, thickly curled luxuriant, hair, a fleshy face, and a soft, effeminate body. The object he once held aloft in his right hand is now missing, but it may have been a wine-cup, because his left hand held tray supports in the form of grapevines, suggesting that the bearer is a young Bacchus. He is usually identified, but without explanation, as a statue that was repurposed as a lampstand (lampadēphoros or lychnophoros). On the contrary, it seems more likely that this too was intended as a piece of furniture, designed in the form of a statue.

The Idolino

The Idolino, now in Florence, was found in 1530 at Pesaro (fig. 8.5).22 The bronze youth was initially identified as a statue by Myron or, more widely, by Polykleitos, and an elaborate, highly decorated base was made for him by Sebastiano Serlio during the 1530s, to which his small, round ancient base was affixed. Little attention was paid to the tray-support made of grapevines that was found with the statue. Mario Iozzo has aptly described the Idolino not as a Roman version of a Classical statue but rather as a “vaguely Polykleitan” piece of furniture.23

An Ephebe in a Pompeiian Wall-Painting

A classicizing statue of a naked ephebe is barely visible standing in the lower right-hand corner of a Pompeiian wall-painting, his feet on a small, round base, his lower arms outstretched to hold a large rectangular tray (fig. 8.6).24 To his left and beside a three-legged round table stands a representation of an actual servant, also a boy, but dressed in a tunic. Larger, mature diners recline behind them, one of them reaching forward for an item on the table. The scene recalls banquet scenes on Greek red-figure vases, in which men reclining on couches are served wine by naked boys with wine-pitchers. These were not meant to be statues, but in Roman dining-rooms silent butlers could stand alongside the actual servants.

The bronze youths may have held lights in a raised hand, or trays on outstretched arms with hors d’oeuvres or cups of wine. The trays are lost, but we can imagine the finest of them, thanks to Pliny the Elder, who writes that citrus-wood tables were as popular with ladies as were pearls with gentlemen. He describes the variety of veining in the citrus-wood, noting that its color gleamed like the wine that was set upon it, and that it was not even damaged by spills (Naturalis historia 13.91–99). Cicero paid 500,000 sesterces for a citrus table, and Gallus Asinius, consul in 8 BC, paid a million sesterces for one. When not in use, a tray and its supports could be removed, the tray-bearer or cupbearer becoming a statue of an ephebe or a youthful Bacchus, to whose hands alternative accessories might be attached. Indeed, there is no evidence that trays and their supports were permanently pinned or soldered to the hands and forearms of these youths.

These three-dimensional images, appointments for the luxury household, recall the Greek traditions represented on red-figure vases that were admired and emulated by the Romans: serving-boys with tables, trays, and pitchers, attending to gentlemen at dinner. Perhaps because the luxury arts have always been difficult for scholars to accept as major arts, there is reluctance to accept the fact that a beloved image like the Idolino is not a famous statue or a derivative of one, but a piece of furniture. Homer and Lucretius called them golden boys—and some of them held lamps, others held trays. They functioned as fine furniture, and they were available in a variety of archaic and Classical styles.

Marathon Boy

An elegantly posed bronze ephebe was netted by fishermen in 1925 near the beach in the Bay of Marathon, with no other finds and no trace of a shipwreck (fig. 8.7).25 The figure was nearly intact, missing only the front of the right foot, which had been separately cast, and a piece of the left heel. Ever since, scholars have argued over what the youth once held on the flattened palm of his left hand, at which he is looking so intently. The Marathon Boy’s right hand is raised, the wrist bent, the thumb and forefinger touching each other, again as if he is holding something. But what was it? Was he pouring liquid into a bowl? Picking fruit and putting it in a bowl? Holding a child, or perhaps a tortoiseshell lyre? Was he holding a box from which he was taking a ribbon? A top? Or was he snapping the fingers of his right hand? Who is he? Is he a young Hermes? Or does the fillet with the leaflike tab at the middle identify him as an athlete?

Some have imagined that the arms had broken off and were restored in Roman times, when he was turned into a lamp-bearer.26 But there is no evidence to support this conjecture. The statue was nearly intact when found, with his arms, legs, and head in place. The only point upon which scholars generally agree is that the style is Praxitelean, late fourth century, or perhaps Early Hellenistic. Was he actually made at that time, or was he a later production, made in the ever-popular Classical style?

Was the Marathon Boy on a ship bound for Italy? Nothing else was found nearby. Why would a ship have jettisoned this bronze in the bay, close to the beach? Could the ephebe have been associated in some way with the sumptuous villa of Herodes Atticus at Marathon, dating to the second century AD? The sculptures in his personal collections were of the highest quality. And so is this figure, though even today we know very little about it. As to its manufacture, we know only what we can see on the surface: the joins of the arms, made with oval flow-welds, appear to be the original joins; they are of a type that is typically found on both Greek and Roman bronzes; and they are in their usual location, below the shoulders, unpatched. One detail that has not been explored is the intentional hole in the left palm, within which there is a cast-in sturdy round pin, well-suited to holding a large object (fig. 8.8). Furthermore, both the hand and the lower arm were flattened in the wax before casting. Did he hold a tray of wine-cups for guests of Herodes Atticus, an oinochoe in his raised right hand? Ridgway had already suggested in 1997 that he might be a server.27 Now this seems likely.

We might ask ourselves what deserves consideration as a statue. If the Marathon Boy were a tray-bearer, could he not also be a statue? As we look at these once-gleaming bronze ephebes with outstretched arms, we might remember that the well-made “golden boys” are first brought to our attention by Homer in the Palace of Alkinoos, and that the genre enjoyed great popularity in sumptuous Roman homes.

Notes

- Louvre inv. Br. 2. H. 115 cm (3 ft. 9 in.). ↩

- I thank Benoît Mille for this observation. ↩

- Ridgway 1967, 43–75. ↩

- See Goodlett 1991, 669–81. ↩

- Descamps-Lequime 2015, 288–91; also Badoud 2015, 281. ↩

- Descamps-Lequime 2015, 288. ↩

- Goodlett 1991, 677–78. ↩

- Benoît Mille reports that the alloy of the fourth toe on the left foot suggests that is an ancient replacement: see here paper #42 by Mille and Descamps, particularly figs. 42.4a-b and 42.5. ↩

- Pompeii 22924; H. 128 cm (50 ½ in.). Vittozzi 1993; Lapatin 2015, 292–93; Pappalardo 2016, 329–30. ↩

- I am grateful to Kenneth Lapatin and Jens Daehner for taking many new measurements of both the Piombino bronze and the Pompeii bronze in October 2015. ↩

- Two of the equal measurements are in the heights of the ears, which are likely to have been added separately in wax. However, the ears of the two bronzes do not seem to be the same. For other bronzes on which the joining of similar parts led to rather different results, see the pairs of mirror-image fountain figures from the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Mattusch 2005, 296–315. ↩

- See recently Pappalardo 2016, 329. ↩

- I am grateful to Ruth Bielfeldt and other participants at the Bronze Congress for making this observation in October 2015. ↩

- I am grateful to Richard S. Mason for this reference. ↩

- Leonard and Smith 1968, 314, n. to lines 2.24–26. ↩

- Naples, MANN inv. 5630. H. with base 150 cm (59 in.). ↩

- Dwyer 1982, 79–80; Mattusch 2014. ↩

- See Ridgway 1970, 136–37. ↩

- Hipkins, Hipkins, and Schlesinger 1911, 177–79. ↩

- Naples, MANN inv. 143753. H. 149 cm (59 in.); with base 162 cm (64 in.). Iozzo 2015, 298; Iozzo 1998, 36–38; Melillo 2013. ↩

- Pompeii 13112. H. 137 cm (54 in.) with base. From the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus (Pompeii VII 16 [ins. Occ.].19). See Varone 1993, 336–39; Mattusch 2008, 43–44; Iozzo 2015, 298; Iozzo 1998, 39–41; and Sodo 2011, 154. ↩

- Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 1637. Height 152 cm (60 in.). ↩

- Iozzo 2015, 298; Iozzo 1998. ↩

- Naples, MANN inv. 120030. This is one of three paintings of banquet scenes from the walls of a room in the House of the Triclinium at Pompeii (V 2.4). See Dunbabin 2003, 58. ↩

- Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. 15118. H. 130 cm (51 in.). Pasquier 2007, 112–15. ↩

- Lullies 1960, 93; Pasquier 2007, 112–15; Calligas 1989; Mattusch 1996, 15–16. ↩

- Ridgway 1997, 343–44. ↩

Bibliography

- Badoud 2015

- Badoud, N. 2015. Le temps de Rhodes: Une chronologie des inscriptions de la cité fondée sur l’étude de ses institutions. Munich: Beck.

- Calligas 1989

- Calligas, P. 1989. “Statue of a Young Athlete.” In Mind and Body: Athletic Contests in Ancient Greece, ed. O. Tzachou-Alexandri, trans. T. Cullen, 179–81. Athens: Ministry of Culture.

- Daehner and Lapatin 2015

- Daehner, J. M., and K. Lapatin, eds. 2015. Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; Florence: Giunti.

- Descamps-Lequime 2015

- Descamps-Lequime, S. 2015. “Statue of Apollo (Piombino Apollo).” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 288–91.

- Dunbabin 2003

- Dunbabin, K. M. D. 2003. The Roman Banquet: Images of Conviviality. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Dwyer 1982

- Dwyer, E. J. 1982. Pompeiian Domestic Sculpture. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Goodlett 1991

- Goodlett, V. C. 1991. “Rhodian Sculpture Workshops.” AJA 95: 669–81.

- Hipkins, Hipkins, and Schlesinger 1911

- Hipkins, K. S., A. J. Hipkins, and K. Schlesinger. 1911. s.v. “Lyre.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 11th ed., 17: 177–79. Cambridge and New York.

- Iozzo 1998

- Iozzo, M. 1998. “… qual era tutto rotto”: L’enigma dell’Idolino di Pesaro: Indagini per un restauro. Exh. cat. Florence: Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

- Iozzo 2015

- Iozzo, M. 2015. “Ephebe (Idolino from Pesaro).” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 298–99, no. 51.

- Lapatin 2015

- Lapatin, K. 2015. “Statue of Apollo (Kouros).” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 292–93, no. 48.

- Leonard and Smith 1968

- Leonard, W. E., and S. B. Smith, eds. 1968. T. Lucreti Cari, De Rerum Natura. Madison, Milwaukee, London: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Lullies 1960

- Lullies, R. 1960. Greek Sculpture. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Mattusch 1996

- Mattusch, C. 1996. The Victorious Youth. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Mattusch 2005

- Mattusch, C. 2005. The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculpture Collection. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Mattusch 2008

- Mattusch, C. 2008. Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture around the Bay of Naples. Exh. cat. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art.

- Mattusch 2014

- Mattusch, C. 2014. “Portrait, Brunnenfigur, Götterbild. Skulpturen als Ausstattungselemente in der Casa del Citarista.” In Pompeji: Götter, Mythen, Menschen, ed. V. Sampaolo and A. Hoffmann, 86–93. Hamburg: Hirmer.

- Melillo 2013

- Melillo, L. 2013. “The Ephebe from the Via dell’Abbondanza: History of a Restoration.” In The Restoration of Ancient Bronzes: Naples and Beyond, ed. E. Risser and D. Saunders, 57–63. http://www.getty.edu/museum/symposia/restoring_bronzes/index.html.

- Pappalardo 2016

- Pappalardo, U. 2016. “I bronzi.” In Caio Giulio Polibio: Storie di un cittadino pompeiano, ed. V. C. Morelli, E. De Carolis, and C. R. Salerno, 329–50. Naples: Assessorato Agricoltura and Istituto per la Diffusione delle Scienze Naturali.

- Pasquier 2007

- Pasquier, A. 2007. “Statue d’un jeune athlète dit Éphèbe de Marathon.” In Praxitèle, 112–15, no. 17. Exh. cat. Paris: Musée du Louvre.

- Ridgway 1967

- Ridgway, B. S. 1967. “The Bronze Apollo from Piombino in the Louvre.” Antike Plastik 7: 43–75.

- Ridgway 1970

- Ridgway, B. S. 1970. The Severe Style in Greek Sculpture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ridgway 1997

- Ridgway, B. S. 1997. Fourth-Century Styles in Greek Sculpture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Sodo 2011

- Sodo, A. M. 2011. “Éphèbe.” In Pompéi: Un art de vivre, ed. P. Nitti, S. De Caro, V. Sampaolo, V. Varone, and A. Varone, 154. Exh. cat. Paris, Musée Maillol.

- Varone 1993

- Varone, A. 1993. “Statua di efebo.” In Riscoprire Pompeii, ed. B. Conticello, 336–39. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Vittozzi 1993

- Vittozzi, S. E. 1993. “Apollo lampadoforo.” In Riscoprire Pompeii, ed. B. Conticello, 262–64, no. 193. Exh. cat. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.