35. Sustainable Conservation of Bronze Artworks: Advanced Research in Materials Science

- Maria Pia Casaletto, Istituto per lo Studio dei Materiali Nanostrutturati, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR-ISMN), Palermo

- Vilma Basilissi, Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione ed il Restauro, Rome

Abstract

The development of nontoxic, reliable, and long-lasting materials and the design of tailored methods for the conservation of bronze artworks are now professional mandates. The presently used hazardous materials and processes need to be replaced by environmentally friendly approaches due to the increasing importance of environmental protection and for the safety of professionals working in the conservation of cultural heritage.

Long-term stability of copper-based archaeological artworks is deeply affected by the nearly constant presence of chlorine in the corrosion layers that can induce the active cyclic copper corrosion known as “bronze disease.” The conventional conservation method applied to ancient bronzes uses a benzotriazole (BTA) alcoholic solution, which unfortunately is toxic and a suspected carcinogen. In order to reduce or overcome the toxicity of BTA, we adopted various tailored strategies of chemical research. Novel chemically synthesized and naturally derived products and suitable nanocarriers of corrosion inhibitors were purposely designed and tested by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscopy coupled with chemical analysis (SEM-EDS), optical microscopy, DC polarization, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS).

Introduction

Conservation Science is a field that has been in continuous evolution since the late twentieth century. The study of ancient bronzes has long focused on archaeometry, addressing technological aspects and production concerns. Casting cores, alloys, joins, surface patinas, and corrosion products have been intensively investigated by various analytical techniques in order to improve our knowledge of the original materials, processes, manufacturing techniques, and degradation phenomena. Scientific results provided very useful information to archaeologists, art historians, and conservators about the artistry, craftsmanship, production, conservation, and restoration of ancient bronze artifacts.

Today, ecological, economic, and social aspects must also be considered when looking at the solutions that scientific research could bring in this field. Taking these new obligations into account, it is clear that a certain number of best practices must be reevaluated and new studies in the field of conservation are required.

Understanding the processes that lead to deterioration is a fundamental element of the concept of conservation. Immediately after its manufacture, any object starts to interact with the atmosphere and the environment and is subject to increasing stress due to normal use. With few exceptions, all metals are subject to corrosion by chemical reaction with the environment.

In some cases, corrosion effects on historic and artistic artifacts can be seen as positive, as for example when a patina is considered aesthetically pleasant; in most cases, however, corrosion produces irreversible damage resulting in the loss of specific values (historic, artistic, scientific, social, etc.) of the object.1 Corrosion induces alteration of the original patinas, and continuous deterioration results in irreplaceable loss of details. A metal may suffer from two different types of corrosion: “dry corrosion,” usually in the form of a thin surface patination or tarnishing, and “aqueous corrosion,” where the metal is attacked more vigorously.

“Bronze Disease”: A Post-burial Degradation Phenomenon

Degradation processes occur as the object reacts to its archaeological burial and post-excavation environments (storage or exhibition). These reactions represent a big challenge for the conservation of metallic artworks, especially in the case of ancient bronzes. Copper-based artifacts may suffer from a pronounced electrochemical corrosion caused mainly by the presence of unstable species (chlorine) that could induce active cyclic copper corrosion, also known as “bronze disease.”

In the framework of several international and national projects carried out in the last decade,2 we investigated the corrosion products of a large number of ancient bronze artifacts excavated in the Mediterranean Basin as a function of the chemical composition, the metallurgical features of the alloy, the archaeological context, and the post-burial degradation. The chemical, physical, morphological, and metallurgical characterization of bronzes sampled in different conservation conditions was performed by means of scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and optical microscopy (OM). The results provided good insight into the corrosion layers and evidenced the nearly universal presence of chlorine as cuprous chloride (CuCl). A complex microchemical structure of the corrosion products, grown during the long archaeological burial, was frequently detected. The most common copper corrosion products are listed in table 35.1. The dangerous basic chlorides resulting from “bronze disease” are marked with asterisks.

| Chemical Compound | Mineralogical Name | Chemical Formula | Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxides | Cuprite | Cu2O | Red/Orange |

| Tenorite | CuO | Black Gray | |

| Carbonates | Malachite | CuCO3 Cu(OH)2 | Green |

| Azurite | 2 CuCO3Cu(OH)2 | Blue | |

| Chalconatronite | Na2(CuCO3)2 3 H2O | Green/Blue | |

| Chloride | Nantokite | CuCl | Green/White |

| *Basic Chlorides | *Atacamite | Cu2(OH)3Cl | Green |

| *Paratacamite | Cu2(OH)3Cl | Pale Green | |

| *Botallakite | Cu2(OH)3Cl | Pale Green/Blue | |

| Sulphides | Chalcocite | Cu2S | Black |

| Covellite | CuS | Black | |

| Sulphate | Brochantite | CuSO4 2 Cu(OH)2 | Green |

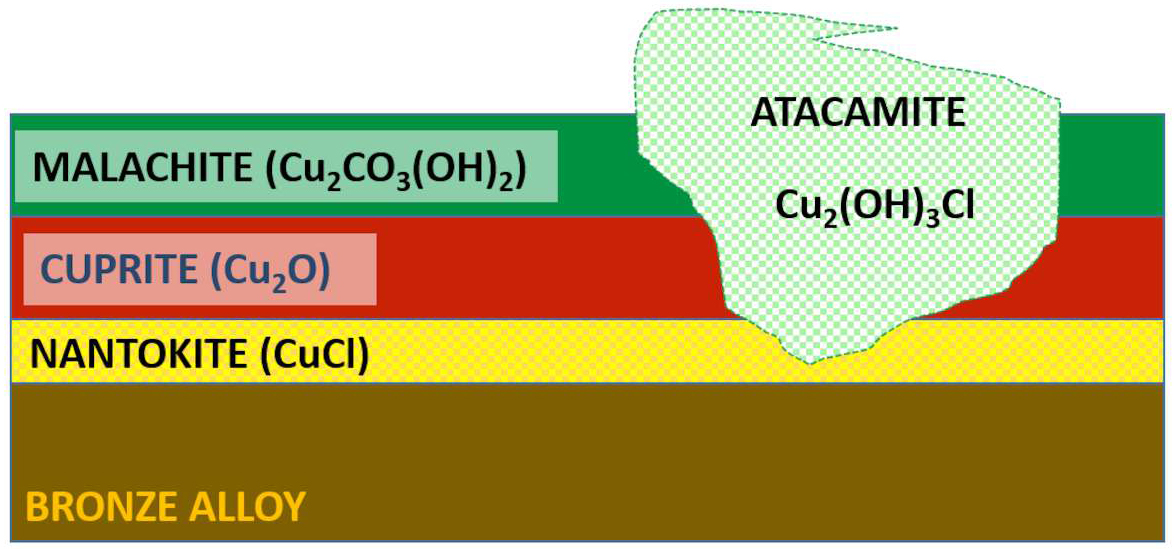

Long-term stability of Cu-based artworks is deeply affected by the cyclic copper (Cu) corrosion induced by air exposure (RH>35%) of the reactive cuprous chloride (CuCl) that is located at the interface between external corrosion products and the surviving core metal matrix.3 Pitting corrosion attacks develop underneath the corrosion products, deep in internal areas of the alloy, with typical pinpoint forms (pits) or craters, and only later appear on the surface. At this point, the state of conservation of the artifacts is irremediably compromised (fig. 35.1), and an appropriate stabilization intervention is necessary to prevent further damage.

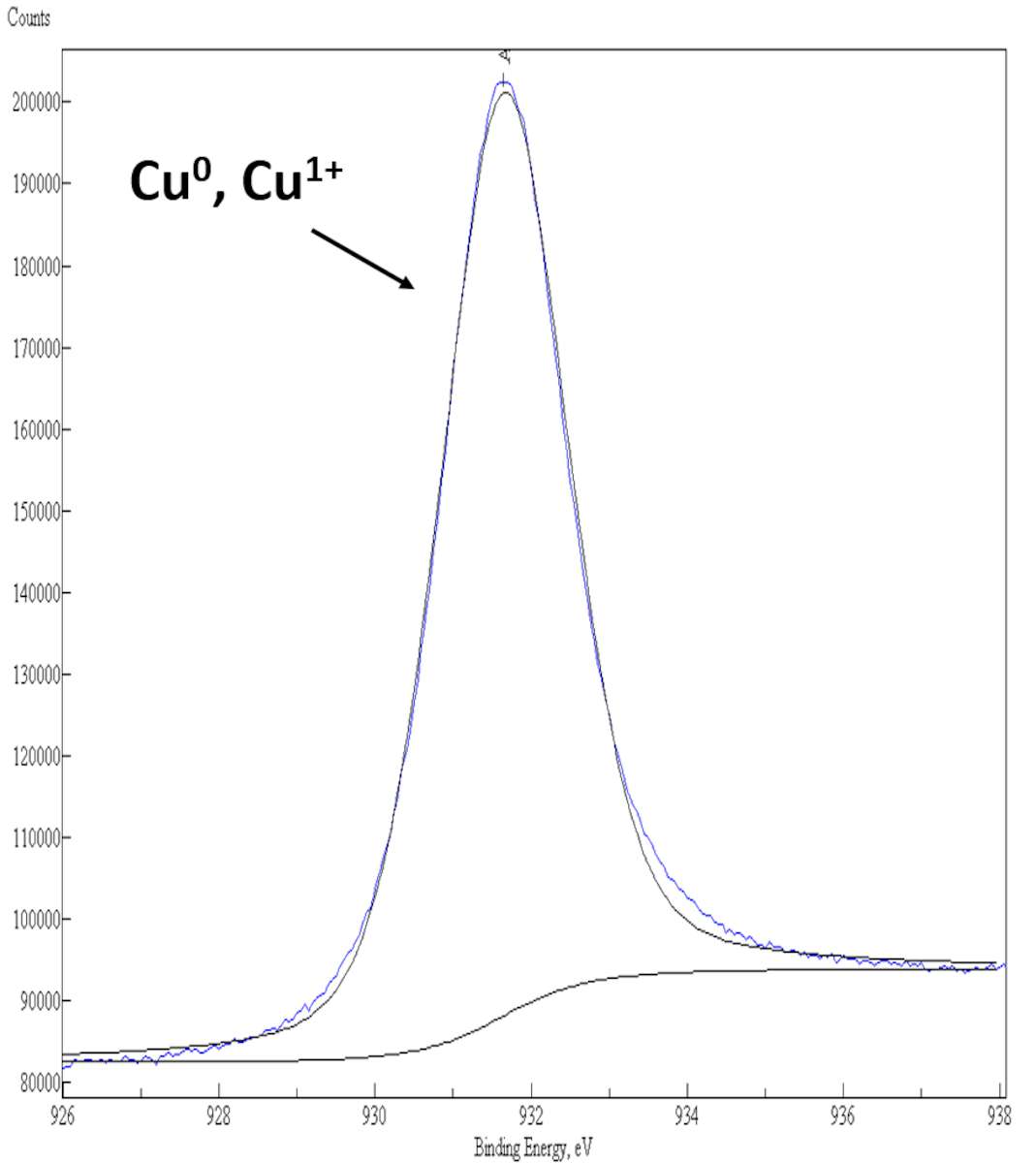

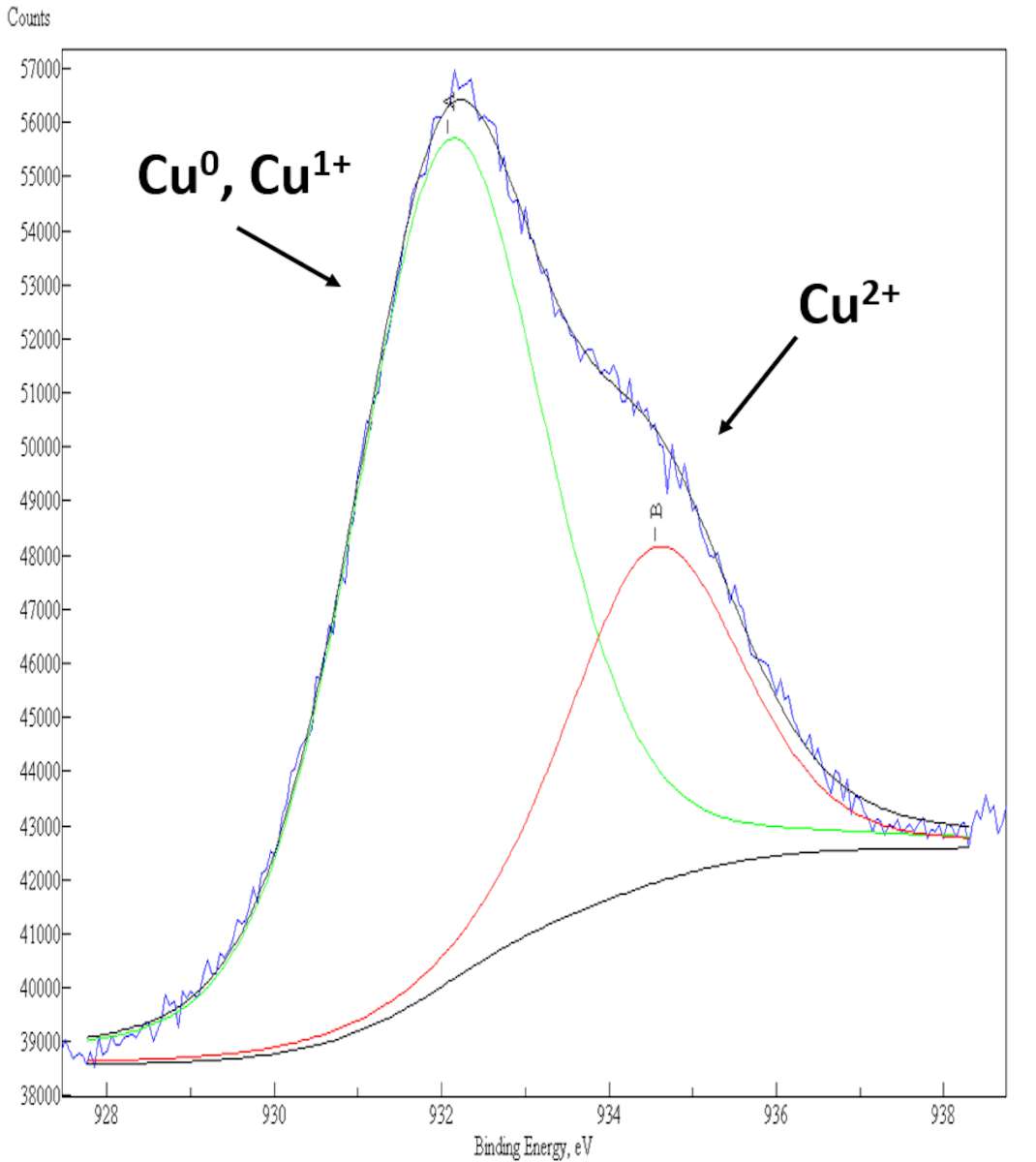

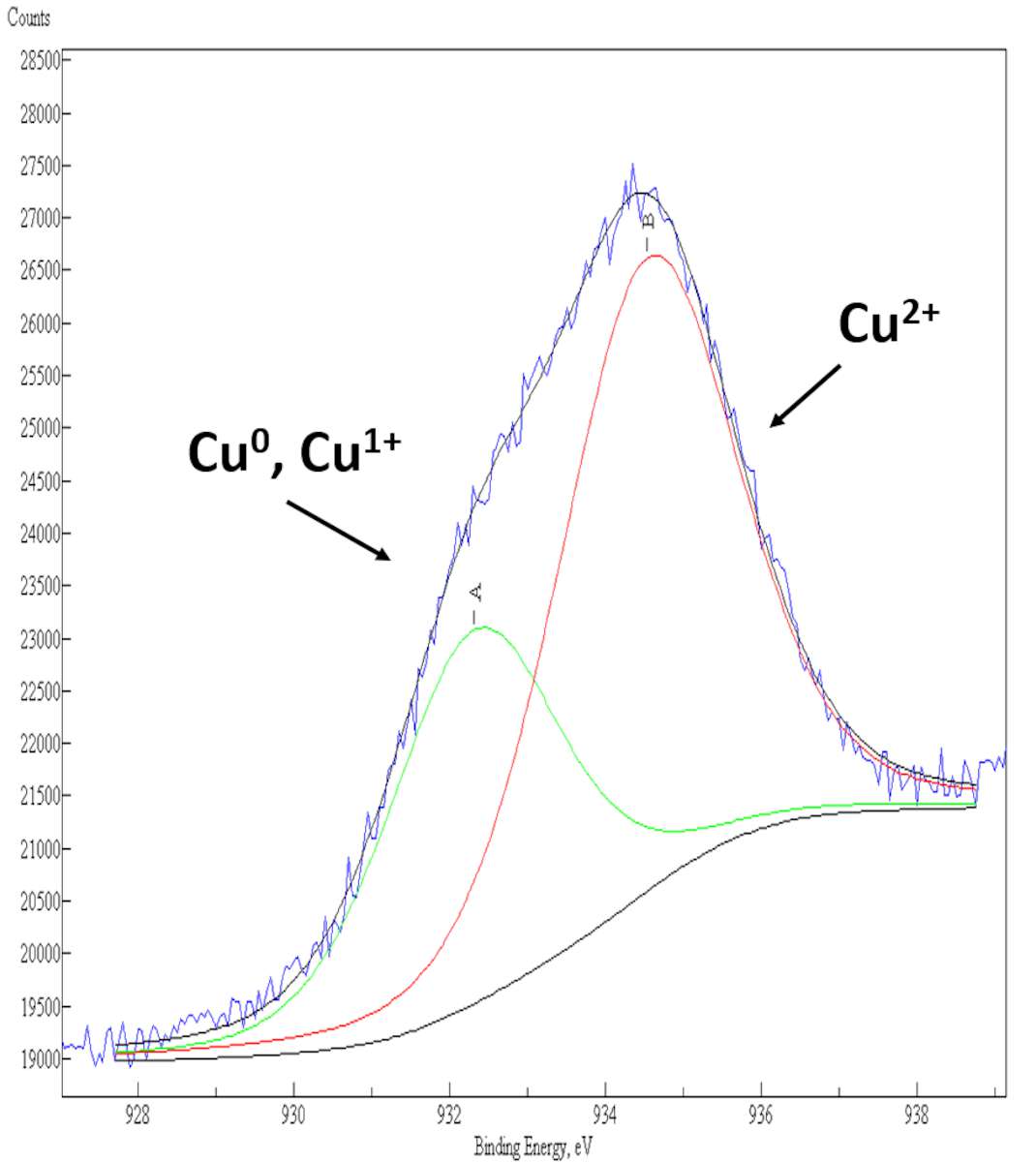

Results of the XPS curve-fitting of the Cu 2p3/2 photoelectron peak from the surface of a pure bronze alloy and from various archaeological artifacts corroded by “bronze disease” are shown here (fig. 35.2). In a pure bronze alloy, the Cu 2p3/2 photoelectron signal consists of a single component centered at a binding energy (BE) value around 932.0 eV, that is assigned to Cu0, Cu+1 species on the surface (see fig. 35.2a). In corroded bronze samples, the presence of a second component located at BE = 934.5 eV in the XPS Cu 2p3/2 spectrum clearly indicates a fraction of Cu+2 species on the surface, whose relative quantity is related to the extent of corrosion suffered by the ancient bronzes (see figs. 35.2b–c).

Conservation Requirements

Restoration and conservation of ancient metals can be carried out by specialists in different ways. However, the identification of an appropriate project of restoration, addressing specific and defined problems of deterioration, is not a simple task. A huge bibliography has developed regarding the relevance, reversibility, and efficacy of traditional and modern methods, products, and materials for restoration.

Various strategies can be used to prevent or reduce corrosion. Since the physical nature of the historic or artistic object cannot be changed, the modification of the environment should be the first choice: preventive conservation strategies involve no action on the object itself (passive techniques) and are therefore preferable from the point of view of current conservation ethics.4

In outdoor environments, this approach is very difficult to implement: atmospheric humidity cannot be controlled, so the main conservation method consists of protecting the artifacts from direct precipitation5 and keeping them under constant maintenance. This strategy is more easily applied in indoor environments, such as museums, where the microclimate (relative humidity, temperature, lighting, and pollution) can be controlled. But even there it is sometimes not economical or practical to act on the environment, especially for objects kept in storage. In this case conservation science offers protocols to either protect the metal surface from contact with the environment and/or reduce the electrochemical reaction rates (active techniques).

In the conservation of metals, one of the most difficult tasks is the stabilization of copper-based alloys coming from archaeological artifacts or from artworks in indoor or outdoor exhibitions. Generally, the treatment consists of the following steps: pre-consolidation; mechanical/chemical/electrochemical/physical cleaning; washings and soluble salts control; dehydration and final stabilization, commonly by using 1-H benzotriazole (BTA) as a corrosion inhibitor. Control in a humidity chamber; consolidation; assembly; filling; surface coating; and mount-making are subsequent treatments to complete a restoration process.

The stabilization of a bronze artifact to slow the natural process of corrosion is one of the most difficult phases of the metal conservation process. The treatment options are varied and can work directly on the pitting phenomenon or on the extraction, to the extent possible, of chlorides before adding chemicals to the system to prevent cyclic corrosion and to prolong the life of the ancient bronzes. Many chemical products can form a protective layer of molecular thickness that prevents the metal from reacting with the environment. Other chemicals, acting as corrosion inhibitors, may take the form of deposits or films that form over the metal, passivating it6 and hence preventing any further corrosion; or they may work as vapors (vapor phase inhibitors, or VPIs)7 by bombarding the metal with molecules.8

Since the first papers dealing with the BTA application for copper appeared in the late 1960s,9 the number of scientific studies on the application of corrosion inhibitors to bronze heritage conservation has increased hugely and their quality has significantly improved, especially in the last fifteen years. Nevertheless, the conventional method used by restorers worldwide for the stabilization of the active corrosion of copper-based artifacts involves ethanolic solutions of BTA as a corrosion inhibitor. These BTA solutions, often concentrated (3–6 wt.%) and heated to 60°C, are usually applied to the objects by brushing, immersion, or spraying. After treatment the object is lacquered to prevent the physical rupture of BTA films and contamination by dirt and sweat. Since BTA is destabilized by UV light, a special commercially available lacquer (Incralac) is commonly used because it contains a reserve of BTA and also a UV screening agent (Paraloid B44 + BTA 3%).

Unfortunately, even though it has been extensively used as a copper corrosion inhibitor, BTA has not always proved effective. Furthermore, BTA is highly toxic and a suspected carcinogen, representing a severe health and environmental risk.10 Since environmental concerns and the safety of conservators should be prioritized in the conservation of cultural heritage, hazardous materials should no longer be used in daily practice. Instead, wherever possible, safe alternatives using environmentally friendly and sustainable materials and processes should be employed.

The stabilization and protection of heritage metals have specific needs and requirements and, necessarily, all the scientific studies on corrosion inhibitors for this application should address and follow these specifications. Commercial corrosion inhibitors satisfy some of these requirements, and in most cases the inhibitor protective layers are transparent. Unfortunately, in other cases, application of the inhibitors produces visible changes. In addition, due to their low thickness, they are susceptible to mechanical removal, so they must in many cases be used in combination with protective coatings, which increase the barrier effect of the whole system. The combination of different inhibitors seems to be a promising way to take advantage of their synergetic effects and to reduce the dosage of chemicals. Still, the toxicity of bronze corrosion inhibitors remains an open question that urgently needs a solution.

Recent Advancements in Material Science

For more than a decade, research activities in our group at CNR-ISMN were devoted to studies of archaeological bronzes in order to find conservation strategies tailored to their chemical composition, structure, archaeological sites, and degradation mechanisms.11 Our scientific approach, represented schematically in fig. 35.3, started with the identification of the degradation agents and mechanisms based on a large-scale diagnostic investigation of different bronze artifacts selected from several archaeological sites of the Mediterranean Basin. These scientific results were extremely important for the production of sustainable nanostructured materials with corrosion inhibition properties to be used as possible alternatives to BTA. In order to test their efficacy as corrosion inhibitors, reference bronze alloys and artificially corroded samples were also produced as sacrificial materials.12 Only the most promising and low- or nontoxic materials resulting from our tests were then submitted to the final validation performed by a conservator on a real ancient bronze artifact.

Experimental Conditions

Reference and/or commercial bronze alloys were used as metallic substrates, after mechanical polishing by silicon carbide abrasive papers with different roughness. Formulations of synthetic or naturally derived products were prepared in ethanol solutions. Films were produced by immersion of the bronze substrate for 2 hours at room temperature. The corrosion treatment was performed by immersion for 2 hours in an aqueous solution of NaCl 3% wt. A detailed surface and electrochemical investigation was performed by using XPS and SEM/EDX, and potentiodynamics and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), respectively. Toxicity studies were carried out by assessment of the acute toxicity (LD50) after oral administration or injection to a population of cavies, according to standard pharmacological protocols. Furthermore, the viability of human bronchial and epithelial cells was tested after exposure.

Organic Corrosion Inhibitors

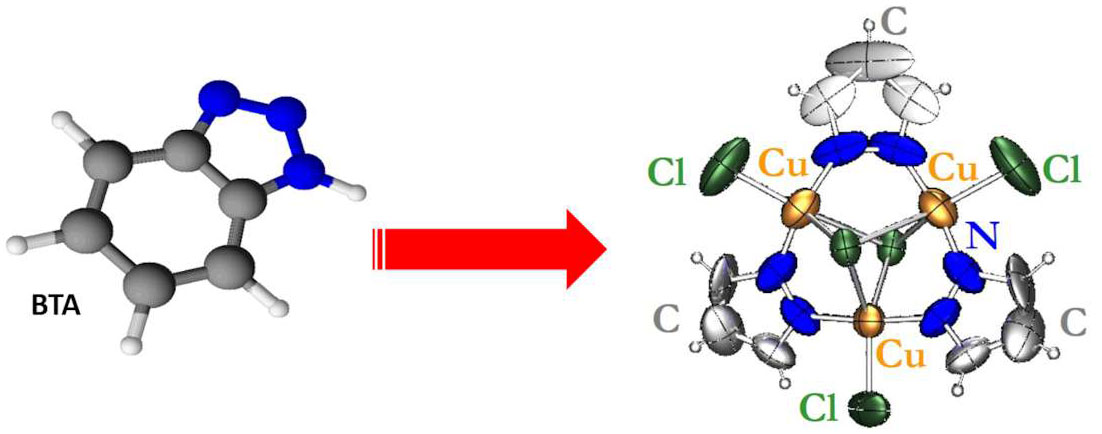

In order to find a possible substitute for BTA, we synthesized different functionalized organic compounds with protective and/or inhibition properties for the conservation of archaeological bronzes.13 In the molecular design of a new organic compound, containing nitrogen and/or sulfur moieties (fig. 35.4), there were certain requirements to be fulfilled for application as corrosion inhibitor. The ideal molecule should have high efficiency in the inhibition of bronze corrosion, low toxicity, environmentally friendly behavior, and long-term stability. Since this product is meant to be applied on real archaeological bronzes, other conservation requirements needed to be considered, such as the preservation of the aesthetic value, the ease of application, and the long-term performance.

A large number of chemical compounds belonging to different classes of organic molecules (e.g., imidazoles, malonamides, oxalamides, aminoalcohols, aminopyrroles) were purposely synthesized for application in bronze conservation. Unfortunately, we encountered many failures, due to to synthetic problems (accessibility of reagents, difficult synthetic routes, low yield of the product); low solubility; the formation of a colored solution; the toxicity of the molecule; and the cost of the production. Since this strategy of chemical synthesis proved to be very time-consuming, with too many requirements to be fulfilled and, consequently, with a high risk of failures, we tried to follow a different approach by investigating natural compounds extracted from the seeds of endemic plants.

“Green” Corrosion Inhibitors

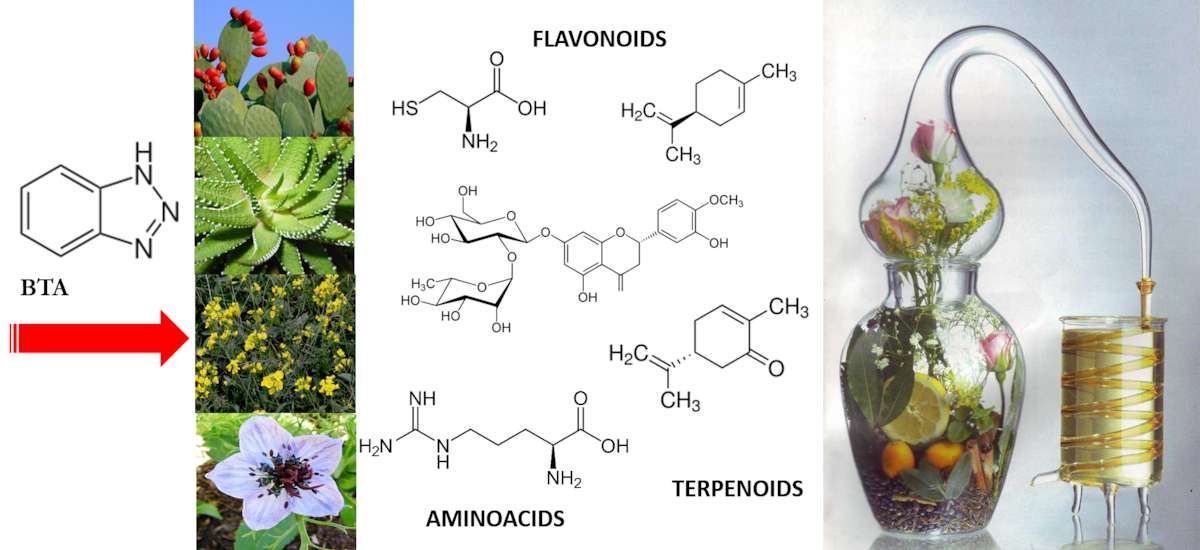

Using eco-friendly compounds derived from extracts as “green” corrosion inhibitors represents a very up-to-date trend.14 They are readily available, usually environmentally friendly, and also biocompatible. Unfortunately, they have a complex chemical nature that, together with the complexity of the heritage bronzes, makes it difficult to understand the mechanisms of protection and/or inhibition or the reasons for their failure. In this field of scientific research, a fundamental screening of literature data should be performed according to what part of the natural species is considered. Essential oils or extracts from the seeds or from leaves yield different chemical compositions which in turn result in different performances and properties. In our laboratories we focused on new formulation based on oil extracted from the seeds of plants widely available in the Mediterranean Basin (fig. 35.5).15

New formulations based on the oil extracted from the seeds of Opuntia ficus indica and the seeds of Nigella sativa were investigated for bronze corrosion in a marine environment (3% NaCl solution).16 The Opuntia ficus indica formulation performed best, and the product was regularly licensed. Our good result allowed the application of this “green” formulation on some bronzes from the Roman collection of the Archaeological Museum of Rabat (Morocco), which are on display in the exhibition rooms in good conservation conditions.

Smart “Self-Healing” Coatings

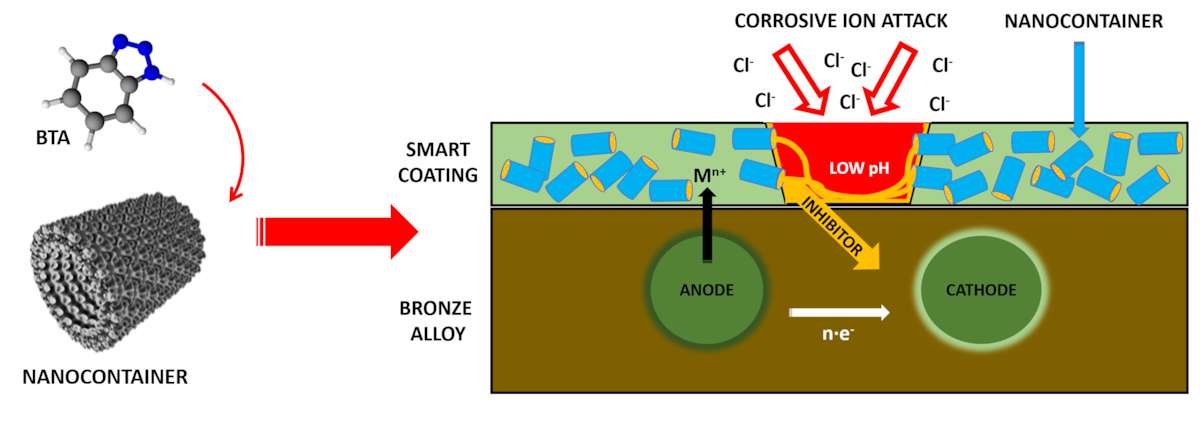

Due to the encountered problems (solubility, colored solutions, toxicity, etc.) that limited or excluded the possible application of some chemicals and formulations on archaeological items, we decided to use a totally different scientific approach: using suitable nanocontainers of corrosion inhibitor to reduce BTA toxicity for the production of smart coatings, as schematically represented in fig. 35.6.

Technologies of encapsulation, delivery, and release of various materials (e.g., drugs, oils, or perfumes) are among the most rapidly developing areas of modern materials science, biotechnology, nanomedicine, and cosmetics. A key point is the development of nanocontainers able to effectively encapsulate the desired active materials, successfully maintaining them in the inner cavity over long time periods and preventing their leakage into the environment. An immediate or prolonged release of the encapsulated active material can be triggered by specific changes in the external environment or directly in the container shell.

Halloysite clay (Al2Si2O5(OH)4·nH2O) nanotubes were investigated as tubular containers of BTA.17 They represent one of the most promising materials among other cylindrical nanocontainers, due to their availability, low cost ($4/kg; supply of 50,000 tons per year), environmentally friendly and biocompatible nature, and ease of processing with many polymeric materials.18 The release properties of the nanocontainer could be fruitfully used for the delivery and targeting of BTA toward the main active corrosion site. The release of BTA is triggered by the corrosion process, which prevents the spontaneous leakage of the corrosion inhibitor out of the coating. If BTA-loaded nanocontainers are incorporated into an organic matrix, the “smart” coating can act both as protection barrier and corrosion inhibitor. We tested this possibility by using hydroxycellulose as the organic compound, just to check the feasibility of our system.19

Conclusion

The scientific literature on bronze corrosion inhibitors is huge, but the vast majority of studies deal with fundamental aspects of corrosion inhibition or industrial applications. Recently, there is an open field of studies in continuous evolution, based on the problem of bronze stabilization by means of eco-compatible and safe new products. In most cases, research is still confined to experimental context and to model surfaces. Usually the inhibitors are applied to pure standard bronze alloys, even though in heritage conservation they would be applied on real ancient surfaces, often over pre-existing corrosion products (or patinas) that have to be preserved with a specific conservation protocol. Advancements are required in the investigation of other properties of the coating, including long-term stability, and in the testing on artificially corroded bronze surfaces, in order to mimic the real behavior of archaeological bronze artifacts. The final validation of these products should be made by the conservator using a specific methodology adapted to the particular needs and conditions of their use on precious ancient bronzes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the PON03PE_00214_1 Project: “Nanotecnologie e nanomateriali per i Beni Culturali,” TECLA, Distretto di Alta Tecnologia per l’Innovazione nel settore dei Beni Culturali della Regione Sicilia, is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

- Basilissi and Marabelli 2008. ↩

- Ingo et al. 2007, ATENA Project final report; Casaletto et al. 2007, 20–25; Degrigny et al. 2007, 31–37. ↩

- Angelucci et al. 1978. ↩

- Preventive conservation is defined as “all measures and actions aimed at avoiding and minimizing future deterioration or loss. They are carried out within the context or on the surroundings of an item, but more often a group of items, whatever their age and condition. These measures and actions are indirect—they do not interfere with the materials and structures of the items. They do not modify their appearance.” From ICOM-CC, “Terminology to Characterize the Conservation of Tangible Cultural Heritage,” resolution adopted by the ICOM-CC membership at the 15th Triennial Conference, New Delhi, 2008. ↩

- Cleaning followed by coating with acrylic lacquers or waxes has become a common method for preserving outdoor bronze sculpture. ↩

- Passivation is obtained by forming a protective and homogeneous layer of corrosion products on the surface of the metal that isolates the metal from the environment. ↩

- It should be noted that in high concentrations, VPIs are toxic. ↩

- Skerry 1985; Turgoose 1985. ↩

- For example, Madsen 1967; Greene 1971. ↩

- Oddy 1974; Sease 1978; Pillard et al. 2001; Selwyn 2004. ↩

- Casaletto et al. 2007; Degrigny et al. 2007. ↩

- Casaletto et al. 2006; Casaletto et al. 2010. ↩

- Ingo et al. 2007, ATENA Project final report; Dermaj et al. 2011; Salvaggio et al. 2012; Dermaj et al. 2015. ↩

- Zaferani et al. 2013, 652. ↩

- Casaletto and Hajjaji 2010; Casaletto et al. 2012. ↩

- Hammouch et al. 2007; Chellouli et al. 2016. ↩

- Lazzara and Milioto 2010; Casaletto et al. 2013. ↩

- Abdullayev et al. 2013. ↩

- Casaletto et al. 2016; Metal 2016. ↩

Bibliography

- Abdullayev et al. 2013

- Abdullayev, E., V. Abbasov, A. Tursunbayeva, V. Portnov, H. Ibrahimov, G. Mukhtarova, and Y. Lvov. 2013. “Self-Healing Coatings Based on Halloysite Clay Polymer Composites for Protection of Copper Alloys.” Applied Materials & Interfaces 5(10): 4464–71.

- Angelucci et al. 1978

- Angelucci, S., P. Fiorentino, J. Kosinkova, and M. Marabelli. 1978. “Pitting Corrosion in Copper and Copper Alloys: Comparative Treatment Tests.” Studies in Conservation 23: 147–56.

- Basilissi and Marabelli 2008

- Basilissi, V., and M. Marabelli. 2008. “Le patine dei metalli: implicazioni teoriche, pratiche, conservative.” In L’arte fuori dal museo: Problemi di conservazione dell’arte contemporanea, ed. S. Rinaldi, 74–89. Rome: Gangemi.

- Casaletto and Hajjaji 2010

- Casaletto, M. P., and N. Hajjaji. 2010. “Development of New Non-toxic Corrosion Inhibitors for Protecting Copper-based Archaeological Artefacts.” Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation (BROMEC) 32: 5.

- Casaletto et al. 2006

- Casaletto, M. P., T. De Caro, G. M. Ingo, and C. Riccucci. 2006. “Production of Reference ‘Ancient’ Cu-based Alloys and Their Accelerated Degradation Methods.” Applied Physics A 83(4): 617–22.

- Casaletto et al. 2007

- Casaletto, M. P., F. Caruso, T. de Caro, G. M. Ingo, and C. Riccucci. 2007. “A Novel Scientific Approach to the Conservation of Archaeological Copper Alloys Artifacts.” In Proceedings of Metal 2007, International Conference on Metals Conservation, Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, Amsterdam, 17–21 September 2007, 2: 20–25. Amsterdam: ICOM-CC Metal WG.

- Casaletto et al. 2010

- Casaletto, M. P., G. M. Ingo, C. Riccucci, and F. Faraldi. 2010. “Production of Reference Alloys for the Conservation of Archaeological Silver-based Artefacts.” Applied Physics A 100(3): 937–44.

- Casaletto et al. 2012

- Casaletto, M. P., R. Licciardi, A. Lombardo, G. M. Ingo, H. Hammouch, M. Chellouli, N. Bettach, N. Hajjaji, and A. Srhiri. 2012. “Surface and Electrochemical Investigation of New Green and Low Toxic Bronze Corrosion Inhibitors.” In Proceedings of European Corrosion Congress EUROCORR 2012, Istanbul (Turkey), 9–14 September 2012. Istanbul: Istanbul Technical University.

- Casaletto et al. 2013

- Casaletto, M. P., R. Schimmenti, and G. Lazzara. 2013. “Smart Nanostructured Corrosion Inhibitor Coatings for the Protection of Cu-based Artifacts.” In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Surfaces, Coatings and Nanostructured Materials - NANOSMAT 2013, Granada, 22–25 September 2013, 237. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Casaletto et al. 2016

- Casaletto, M. P., C. Cirrincione, A. Privitera, and V. Basilissi. Forthcoming. “A Sustainable Approach to the Conservation of Bronze Artworks by Smart Nanostructured Coatings.” In Proceedings of Metal 2016, 9th interim meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, New Delhi, 26–30 September 2016, in press.

- Chellouli et al. 2016

- Chellouli, M., D. Chebabe, A. Dermaj, H. Erramli, N. Bettach, N. Hajjaji, M. P. Casaletto, C. Cirrincione, A. Privitera, and A. Srhiri. 2016. “Corrosion Inhibition of Iron in Acidic Solution by a Green Formulation Derived from Nigella sativa L.” Electrochimica Acta 204: 50–59.

- Degrigny et al. 2007

- Degrigny, C., V. Argyropoulos, P. Pouli, M. Grech, K. Kreislova, M. Harith, F. Mirambet, N. Haddad, E. Angelini, E. Cano, N. Hajjaji, A. Cilingiroglu, A. Almansour, and L. Mahfoud. 2007. “The Methodological Approach for the PROMET Project to Develop/Test New Non-toxic Corrosion Inhibitors and Coatings for Iron and Copper Alloy Objects Housed in Mediterranean Museums.” In Proceedings of the ICOM-CC Metal 2007, International Conference on Metals Conservation, Amsterdam, 17–21 September 2007, 5: 31–37. Amsterdam: ICOM-CC Metal WG.

- Dermaj et al. 2011

- Dermaj, A., D. Chebabe, N. Bettach, N. Hajjaji, A. Srhiri, M. P. Casaletto, G. M. Ingo, C. Riccucci, and T. de Caro. 2011. “Electrochemical Study of a New Non-toxic Inhibitor Formulation for the Conservation of Archaeological Bronze.” In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress Science and Technology for the Safeguard of Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean Basin, Istanbul (Turkey), 22–25 November 2011, 237. Rome: Centro Copie L’Istantanea.

- Dermaj et al. 2015

- Dermaj, A., D. Chebabe, M. Doubi, H. Erramli, N. Hajjaji, M. P. Casaletto, G. M. Ingo, C. Riccucci, and T. de Caro. 2015. “Inhibition of Bronze Corrosion in 3% NaCl Media by Novel Non-toxic 3-phenyl-1,2,4-triazole thione Formulation.” Corrosion Engineering Science and Technology 50(2): 128–36.

- Greene 1972

- Greene, V. 1972. The Use of Benzotriazole in Conservation: Problems and Experiments. ICOM Report 2/72/2. Paris: ICOM Committee for Conservation.

- Hammouch et al. 2007

- Hammouch, H., A. Dermaj, M. Goursa, N. Hajjaji, and A. Srhiri. 2007. “New Corrosion Inhibitor Containing Opuntia ficus indica Seed Extract for Bronze and Iron Based Artefacts.” In Strategies for Saving Our Cultural Heritage: Papers Presented at the International Conference on Conservation Strategies for Saving Indoor Metallic Collections, Cairo, ed. V. Argyropoulos, A. Hein, and M. A. Harith, eds. 149–55. Athens: TEI.

- Ingo et al. 2007

- Ingo, G. M., M. P. Casaletto, T. de Caro, F. M. Mingoia, C. Riccucci, and G. Chiozzini. 2007. Relazione finale del Progetto ATENA: “Applicazione di metodologie innovative per la conservazione di manufatti metallici e ceramici da scavo archeologico ed il recupero delle relative tecniche di produzione.” CNR-ISMN (2002–2006).

- Lazzara and Milioto 2010

- Lazzara, G., and S. Milioto. 2010. “Dispersions of Nanoclays of Different Shapes into Aqueous and Solid Biopolymeric Matrices: Extended Physicochemical Study.” Langmuir 27: 1158–67.

- Madsen 1967

- Madsen, L. B. 1967. “A Preliminary Note on the Use of Benzotriazole for Stabilizing Bronze Objects.” Studies in Conservation 12.4: 163–67.

- Metal 2016

- Proceedings of Metal 2016, 9th Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, New Delhi, 26–30 September 2016, in press.

- Oddy 1974

- Oddy, W. A. 1974. “Toxicity of Benzotriazole.” Studies in Conservation 19: 188–89.

- Pillard et al. 2001

- Pillard, D. A., J. S. Cornell, D. L. Dufresne, and M. T. Hernandez. 2001. “Toxicity of Benzotriazole and Benzotriazole Derivatives to Three Aquatic Species.” Water Research 35(2): 557–60.

- Salvaggio et al. 2012

- Salvaggio, G., M. P. Casaletto, M. L. Testa, G. Ingo, C. Riccucci, and T. De Caro. 2012. “Surface Characterization of New Corrosion Inhibitors for the Conservation of Archaeological Bronze Artifacts.” Paper delivered at Youth in COnservation of CUltural Heritage (YOCOCU) 2012, Antwerpen (Belgium), 18–20 June 2012.

- Sease 1978

- Sease, C. 1978. “Benzotriazole: A Review for Conservation.” Studies in Conservation 23: 76–85.

- Selwyn 2004

- Selwyn, L. 2004. Metals and Corrosion: A Handbook for Conservation Professionals. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute.

- Skerry 1985

- Skerry, B. 1985. “How Corrosion Inhibitors Work.” In Corrosion Inhibitors in Conservation: The Proceedings of a Conference Held by UKIC in Association with the Museum of London, ed. S. Keene, 5–12. London: UKIC.

- Turgoose 1985

- Turgoose, S. 1985. “Corrosion Inhibitors for Conservation.” In Corrosion Inhibitors in Conservation: The Proceedings of a Conference Held by UKIC in Association with the Museum of London, ed. S. Keene, 13–17. London: UKIC.

- Zaferani et al. 2013

- Zaferani, S. H., M. Sharifi, D. Zaarei, and M. R. Shishesaz. 2013. “Application of Eco-friendly Products as Corrosion Inhibitors for Metals in Pickling Processes – A Review.” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 1(4): 652–57.