32. Bronze Medical and Writing Cases in Classical and Hellenistic Macedonia

- Despina Ignatiadou, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Abstract

Introduction

Parexodos is the name ascribed in the Hippocratic Corpus to the portable medical case that a doctor must own to facilitate work outside his premises. In it, he could store prepared medicaments and also his tools: “ἔστω δέ σοι ἑτέρη παρέξοδος ἡ λιτοτέρη πρὸς τὰς ἀποδημίας ἡ διὰ χειρῶν … [Be sure to possess another portable case, simpler and hand-held for travels … ]” (De decente habitu 8.10–11).1

We are familiar with the medical cases of the Roman period, which are rectangular boxes with sliding lids and rectangular compartments,2 but our knowledge of the medical cases of the Classical and Hellenistic periods remains limited. In Macedonia, older and recent finds illuminate an important production of multi- and single-compartment medical and writing cases of those periods.

Type A Cases: Late Classical Period

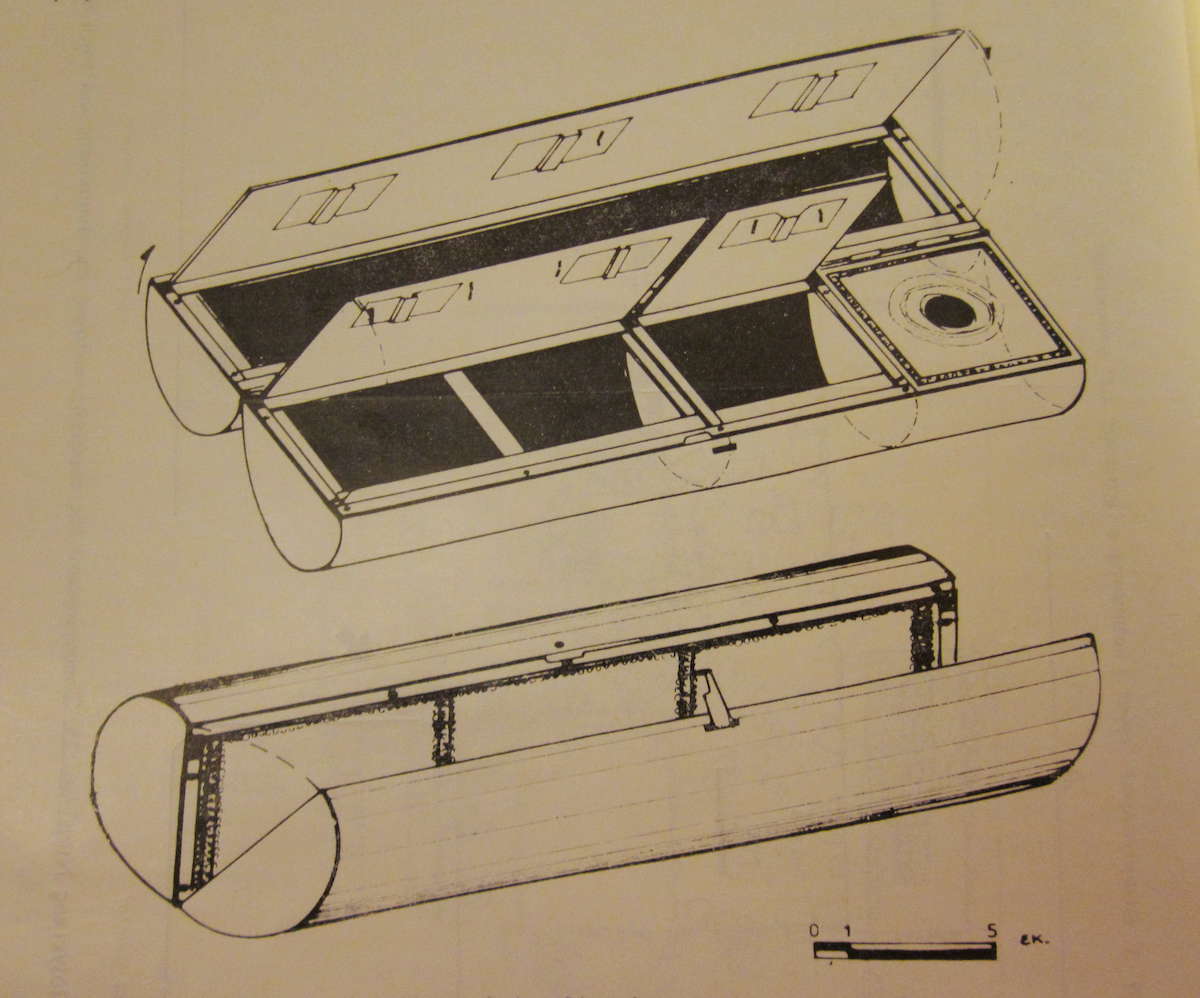

Two cases, from Stavroupolis and Derveni, were found in secure Late Classical contexts and remain the only examples of the Classical period and of this particular type: a cylindrical body comprising two lidded parts, hinged lengthwise. It is very probable that both were made in the same workshop.

The first was found in Stavroupolis in Thessaloniki, on Oreokastrou Street, in a cist grave containing a burial of 350‒325 BC (fig. 32.1a‒b).3 It is the most complete and sophisticated case, found in an elite male burial of a warrior and priest. It consists of two hinged half-cylinders with lidded compartments and a built-in inkwell. The case is fully portable as it could be latch-locked and suspended from two loops at the far right end. The upper half-cylinder has its own internal lid, which is hinged at its outer edges, a movable arched handle, and locks in three places. The lower half-cylinder is divided by transverse sheets into three compartments; the left is one-half the length of the whole, and the other two are one-quarter each. One of the dividers is made of lead, and it could be interpreted as a repair; but this practice is noticed in the Archontiko case too (see below), therefore another interpretation might apply. The first two compartments have their own hinged lids with handles and locks. The right compartment has a removable flat top with a central perforation. Underneath it are the remains of a black substance within a circle. The case is made of yellowish high-tin bronze and all the inner lids and the periphery of the hole are decorated with triple silver-gilt lines with small incisions. It is 22.5 centimeters long, and 5.5 centimeters in diameter when closed. It has been mended and restored.

The deceased in the Stavroupolis burial was a warrior, as we know from his grave goods; however, there are also finds that indicate a religious aspect of his status, such as a set of ritual silver vessels. The most impressive item in the burial was a unique silver-legged stool, a piece of furniture with an established association with the representation of gods, heroes, and priests. The burial had been disturbed by modern digging machinery and the finds were collected rather than excavated. It is probable that the case had been placed in the grave with some other contents that were overlooked or destroyed. As the burial can be dated after the middle of the fourth century BC, the case was probably manufactured in the first half of the same century.

The Stavroupolis case was interpreted as a writing case until recently, when the investigation of the Derveni find, discussed below, led scholars to suspect it was intended instead for medical purposes.

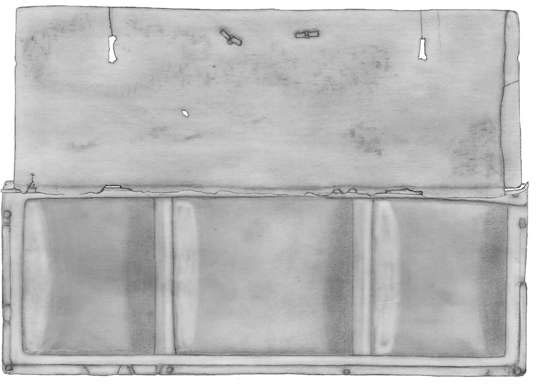

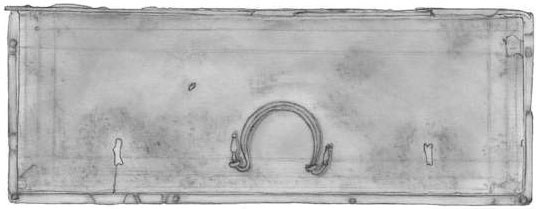

The second case of Type A was found in Derveni, near Thessaloniki, in Cist Grave B with a burial of around 320 BC (fig. 32.2a‒d).4 This burial contained the cremated remains of a man and another individual inside the spectacular Derveni krater. Among the numerous accompanying grave goods was a bronze case (B 35) that still preserved its contents and was interpreted as a cosmetics container. The existence of a second individual in this grave, perhaps a woman, has puzzled researchers because there were no grave goods that could be associated with a woman. In fact, the case presented here was thought to be the main indication for the cremation of a female consort. The find was displayed for more than fifty years with the lid permanently half closed. It is made of high-tin bronze and is divided in three compartments with a flat ledge and a rod fastened on the ledge with copper nails. The lid is made of a single flat sheet, fastened at its extremities with a lengthwise wire rod, and decorated with incised lines along its edges. On the front middle of the lid is an arched handle of ordinary bronze, attached by means of two strips penetrating the sheet and bent underneath. Flanking the handle are two elongated latch holes. One hole and two dents along the right edge of the lid have been patched from behind with a bronze strip. It is 13 centimeters long and 4.9 centimeters wide. Its height when closed is 2.1 centimeters. The lid measures 12.5 by 4.7 by 0.1 centimeter, and the handle is 1.7 by 2.5 centimeters.

Figure 32.2a

Figure 32.2a

Figure 32.2b

Figure 32.2b

Figure 32.2c

Figure 32.2c

Inside the compartments the original contents are preserved: three masses of “clay.” The left and the middle bits appear to have been pinched with naked fingers while the right one had been originally pressed inside a miniature pyxis. On the middle one, a mass of cellulose fibers remains. The inorganic and mineral composition of the three cakes is similar but not identical, and it seems that each one was a deliberate preparation, to be used as medication. Their main constituents are quartz, mica, and chlorite (41‒44 percent), plus 16‒31 percent of amorphous materials. Fifty-three (53) organic fatty acids were determined in traces, for the moment only chemically, and our efforts continue toward determining their origin in particular herbs, oils/fats, or condiments. The finger impressions on the two cakes show that the healer was taking small amounts to administer in the form of pills.5

Other bronze and copper parts related to the Derveni case were retrieved from the same grave (fig. 32.2d):

Lid B 90a (fig. 32.2d, top) is a second, but longer, bronze lid preserving two latches and also repaired. It is 25.2 centimeters long and 4.5 centimeters wide; the bronze sheet is 0.1 centimeter thick. The handle measures 2.5 by 3.2 centimeters, with latch holes 4.5 centimeters from the corresponding short side.

Lid B 90b (fig. 32.2d, bottom middle) is a small square bronze lid with a ring handle, perhaps a replacement part. It is 5.3 centimeters long and 4.5 centimeters wide. The bronze sheet is again 0.1 centimeter thick. The diameter of the ring (handle) is 1 centimeter, while the latch holes are 2.5 centimeters from the left side and 2.3 centimeters from the right.

The bronze lid of B 90c (fig. 32.2d, bottom right) is flat and perforated, decorated with incised lines. It was probably fitted with a small cylinder made of a single flat sheet fastened with a bronze nail; this is evidently the lid of an inbuilt inkwell. It is 5.1 centimeters long and 4.9 centimeters wide, with a sheet thickness of 0.1 centimeter. The diameter of the perforation is 1.4 centimeters.

Two miniature, undecorated, semi-spherical bowls of hammered copper contained remains of a dark cake, of a nature similar to that of the “clays” in Case B 35. The dimensions of the bowls (4.4 cm in diameter, height 2.1 cm) permit the hypothesis that they could originally have fit inside the compartments of the case.

Differences in surface preservation resulted when some were mechanically cleaned, some chemically cleaned, while others are still untreated. Nevertheless, all of these non-assembled parts probably belong to the same original case as the restored Case B 35. The long lid of 90a indicates the full length of the complete case, which probably looked similar to the Stavroupolis one. The wear and repairs show that it had been used for a long time before the interment, around 320 BC, and we can therefore date the manufacture of the find to the first half of the fourth century BC. It is further possible that the complete case was modified so that the now restored part had become detachable; it might then be used independently by the healer, who may have inherited it from his father in continuation of a family tradition.

Companion bronze finds in the burial confirm the medical use of the case: these include a miniature pyxis that contained red hematite powder, a spatula probe, a spatula scoop, a rare catheter/clyster, and numerous stone alabastra that probably originally contained medicaments.

The deceased in Derveni Grave B was a high priest, entitled to be buried inside the krater associated with his cultic duties,6 and also evidently a warrior, since he was buried with his armor and weapons. The inscription on the krater’s rim associates him with Larissa, the workplace of Hippocrates, who also died and was buried there, and consequently with the Hippocratic tradition of Thessalian healers.7

Type B Cases: Late Classical or Early Hellenistic Period

Several other cases have been found in Macedonian burials. These cases also have a semi-cylindrical body, but their compartments may be lidded and/or topped by a flat sheet perforated to give inside access. These perforations are either rectangular or round.

One such case (Case A) was found in Pydna (Kitros, Alykes), in a Macedonian tomb with burials of the third and second centuries BC. Like the others, it is bronze and a semi-cylindrical case with hinged lid,8 dating to the late fourth to early third century BC. Its parts are housed in the Archaeological Ephorate of Pieria/Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki (inv. Py 683, Py 684, Py 686, Py 688) (fig. 32.3).

Three cases were retrieved from this tomb in the south cemetery of ancient Pydna. It was built in the early third century BC but remained in use for successive burials for more than a century. The finds have been treated but not assembled or restored. It is not clear whether Cases A and B (discussed below) were originally used independently or were combined in one cylindrical unit like the Stavroupolis case. Additionally, two bronze lock plates, which may be associated with the cases,9 one small bronze pyxis, and one bronze probe were found in the tomb.

Case A is a nearly complete lidded and latched case with three compartments made of high-tin alloy. Its top has three circular openings, outlined with incised concentric circles. The lid is undecorated and fastened by means of a flat rod. Flanking the handle are two stepped bosses covering the dowels used to turn the latches. The body (Py 684) is a semi-cylindrical curved sheet preserved in four fragments (fig. 32.3, bottom). As preserved, it is 12 centimeters long, 4.8 centimeters wide, and 1.6 centimeters high. The sheet thickness is less than 0.1 centimeter.

The body side (Py 688) consists of one semi-circular sheet; it is probably one short side of Py 684. It measures about 4.7 centimeters (est. because of broken tip) by 2 centimeters, with a thickness of 0.07 centimeter.

The top (Py 686, Py 691) consists of a flat rectangular sheet with three circular openings (fig. 32.3, middle). It was probably fastened on top of the curved sheet (Py 684). Each opening was approximately 3.6 centimeters wide and is outlined with two incised concentric circles at a distance of 0.4 centimeter from each other. From the largest fragment, preserving nearly half the length, we can estimate the total length of this element to be 15.6 centimeters and its width to be at least 4.8 centimeters. The thickness is 0.07 centimeter.

The lid (Py 683, fig. 32.3, top) consists of a single flat sheet with a moving arched handle. On top of its upper surface and along the back long side is attached a flat rod with pointed ends. Both back corners of the lid are missing; it is therefore not possible to see how it was connected to the body. On the front middle of the lid is an arched moving handle with curved-back terminals. The handle was attached to the sheet by means of two strips penetrating the sheet; these survive only partly. Flanking the handle are two stepped bosses covering the dowel attachments of the latches on the other side of the lid, and probably also used to swivel the latches. The bosses are placed at a distance of 1.7 centimeters from the corresponding short sides and 0.6 centimeter from the long side. The latches are made of a contoured sheet (like two back-to-back C-shaped elements) at the end of a long strip, which survives only partly; the latches were obviously swiveling around the dowel so that the protruding strip would catch against an opposite side. The surface is corroded but from the uncorroded patches it is evident that the lid is not decorated with incisions. It was mended but not restored. The lid measures 16.3 by 5.2 centimeters; the handle is 2.9 by 2 centimeters; the bosses are 0.9 centimeter in diameter. The latches (preserved) are 1.2 by 1.2 centimeters; the rod is 16.7 by 0.3 by 0.1 centimeters.

Case B is also a bronze semi-cylindrical (Py 692), preserved at the Archaeological Ephorate of Pieria/Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. It too comes from Pydna, from the same tomb as Case A (fig. 32.4).

Case B is a semi-cylindrical case with three compartments, but it is shorter than Case A. Only the body is preserved, with visible marks on the places where the compartment dividers once were. It is also possible that some of the top parts attributed to Case A belong to this case instead.

The body consists of one nearly complete semi-cylindrical curved sheet, mended but not restored. It was originally divided lengthwise in three compartments. Their exact original places are still visible on the concave side, as straight corrosion lines. Each of the three compartments was approximately 4.7 centimeters long. It is 14.5 centimeters long and about 4.8 centimeters wide (present but distorted width, 4.2 cm), with a height of 2.3 centimeters. The thickness is 0.05 centimeter.

A third case from the Pydna tomb, Case C, is once again a bronze semi-cylindrical case with a perforated top. It is preserved in the Archaeological Ephorate of Pieria/Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki (inv. Py 644, Py 645, Py 687, Py 689, Py 690; fig. 32.5).

Case C is a single compartment case with a recessed top with a square perforation. In the recess fits a bronze “palette” that can slide to cover or uncover the perforation. A lid slightly larger than the top and with a similar perforation was probably fitted on it.

The body of Case C consists of one nearly complete semi-cylindrical curved sheet (Py 690), mended but not restored. It is 6.7 centimeters (its present but distorted width is 4.2 cm), and it is 2.3 centimeters high. The thickness is less than 0.1 centimeter.

The body side of Case C consists of one semi-circular sheet (Py 687), about 3.9 by 1.9 centimeters, with a thickness of 0.05 centimeter. Alternatively, this element could be one of the short sides or a divider of Case B.

The top of Case C is a flat rectangular sheet with a recessed rectangular area and a square perforation (Py 689). It measures 6.8 by 4.7 centimeters. The recessed area is 5 by 3 centimeters and about 2.4 centimeters deep. The flat rim is 0.85 centimeters wide. The thickness is 3.1 centimeters, and the thickness of the sheet is 0.7 millimeters. The perforation is 1 by 1 centimeter.

The “palette” of Case C is a rectangular bronze piece that fits inside the recessed area of the top and can slide to the right or left (Py 645). It is decorated with a set of parallel engraved lines visible along one short side, but these may have continued along all sides. The piece is 3.7 by 3 centimeters with a thickness of 1.5 millimeters. The “lid” of Case C is a rectangular bronze sheet with square perforation and two sets of finely engraved circles around it (Py 644). Underneath, a rough deteriorated area along the sides at the center shows a shinier (silver gilt?) area, more or less corresponding to the recessed area of the top. The piece measures 7.2 by 5.2 centimeters; the perforation is 1.3 by 1 centimeters, and the thickness is 0.1 centimeter.

Our next examples come from Archontiko, near Pella, Pit Grave 325 A of the fourth century BC. Two bronze semi-cylindrical cases with hinged lids10 are preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Pella (fig. 32.6). Two individual lidded cases and two lids were found in a late fourth-century BC burial in the Archaic and Classical cemetery. It is possible that they all belonged to the same sophisticated case. They preserve small quantities of their contents.

Another bronze semi-cylindrical case and stone palette was discovered in Veroia, Building Block 305, on a side street off Ploutarchou Street, in a vaulted rock-cut tomb (Tomb III) with a burial of the late third–early second century BC.11 It is preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Veroia (fig. 32.7). This case, with three compartments and a perforated top, has a long body with two preserved dividers, making one long compartment in the middle and two short ones at the ends. The top has three perforations: two large rectangular ones left and right, and one smaller rectangular at the center right. Thus the central compartment top features two sets of concentric decoration but only one off-center perforation. A lid is not preserved.

Another bronze case with three compartments was unearthed during a rescue excavation at Amphipolis. The dating is uncertain but may be fourth/third century BC.12 The top features one rectangular and two round perforations.

Finally, from the archaeological site at Edessa comes a small, single-compartment bronze case with feet (fig. 32.8). It was found on a rural road, in Grave II with burial of the second century BC.13 The semi-cylindrical body is supported on two contoured sheet feet. It has a flat top with a central small round perforation. There is no lid. It is thought to be an inkwell.

The Greek Tradition of Medical and Writing Cases

Most of the pre-Roman medical cases were probably wooden and have not survived; it is therefore risky to make assumptions as to their shape. Only one, but very important, wooden find testifies to the existence of (semi-)cylindrical cases that appear to have been the forerunners of the Macedonian finds. It is a semi-cylindrical wooden case, unearthed in the “Tomb of the Poet” in Athens, the burial of a musician and author from around 430/420 BC. The case was found together with a bronze stylus, a bronze bowl, remains of five wooden writing tablets, and a papyrus roll.14 Thus the construction of similar bronze cases in fourth-century BC Macedonia appears to be the evolution of an earlier Greek tradition.

The semi-cylinder is an awkward and unstable shape, unless it is associated with a second semi-cylinder to form a cylinder: the perfect shape around which to roll a papyrus sheet. In addition, it is logical to imagine that some semi-cylindrical cases could have originally been incorporated in wooden cylindrical cases, similar in shape to the Stavroupolis find.

This notion of a writing substratum that is rolled around a pen case is known from historical finds. Such a writing case was in the possession of J. W. Goethe and is exhibited in his Weimar house. A similar case in gold-decorated red leather belonged to Napoleon, who gave it as a gift to his friend Marshal Lannes.15 The case proper accommodates pens in the middle, while its two metal ends are an inkwell and an ink-powder container. Like our Classical finds, it is a portable case, but used by army officers for writing letters and orders during military campaigns rather than for medical purposes.

Notes

- Translated by the author. See also Bliquez 2015, 24. ↩

- For example, Boyer, Bel, and Tranoy 1990. ↩

- On the burial and the case, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, inv. MTH 7437, see Romiopoulou 1973‒74; Romiopoulou 1989, 215‒6, no. 23, plate 57; Descamps-Lequime 2011, cat. 228 (D. Ignatiadou); Ignatiadou 2014a, cat. no. 384; Ignatiadou (forthcoming). ↩

- Full publication of the medical set in this burial, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, inv. B 35 and B 90, may be found in Ignatiadou 2015. On the metal composition, see Katsifas et al. forthcoming. On the burial and the case, see Themelis and Touratsoglou 1997, 91, plate 103. ↩

- A find of similar composition was retrieved from the second-century BC Pozzino shipwreck in Tuscany; see Giachi et al. 2013. ↩

- Ignatiadou 2014b. ↩

- See discussion in Ignatiadou 2015. ↩

- Bessios 1985; Bessios 2010, 246‒55. I thank the excavator M. Bessios for the privilege of studying these cases. ↩

- They are nearly square bronze sheets, each with two rectangular perforations perpendicular to each other. At each corner is one hole for a bronze nail; diameter 3 mm. Plate (Py 631): 4.1 x 4.2 cm. Perforations 0.8 x 1.3 and 3.6 x 1.1 cm. Thickness of sheet 0.1 cm. Preserved total thickness 1.3 cm. Mended but complete. It preserves the four nails that are attached underneath to two wooden strips; the nails are longer than the thickness of the wood and their extra length is bent along the strip they penetrate. Plate (Py 685): 3.8 x 4.1 cm. Perforations 0.7 x 1.4 and 0.3 x 1.0 cm. Thickness of sheet 0.1 cm. Mended, with missing parts. ↩

- The finds were excavated in the summer of 2004 and are unpublished. For the opportunity to see photographic documentation of their parts and to examine the content remains, I sincerely thank the excavator Pavlos Chrysostomou and the conservator of antiquities Evangelos Chrysostomou. The two-lidded cases were displayed in the exhibition Before the Great Capital, in the Archaeological Museum of Pella, in 2016. ↩

- The find is unpublished. For the opportunity to illustrate it here I thank the excavator Angeliki Koukouvou. For a brief report on the excavation, see Koukouvou 1996. ↩

- Archaeological Museum of Amphipolis? The find is unpublished. It was shown in a past meeting of the Archaeological Work in Macedonia and Thrace. ↩

- Chrysostomou 2013, 189, plate 72, cat. 415, 433, 434, and 435. ↩

- Pöhlmann 2013, 12‒4, plate I 8b. ↩

- Dated 1804–09. 33.2 x 6.3 cm. Fondation Napoléon, Paris. http://www.napoleon.org/en/collectors_corner/object/files/486393.asp (accessed 4-10-2015). ↩

Bibliography

- Bessios 1985

- Bessios, M. 1985. “Der Grabhügel von Alykes bei Kitros.” In The Archaeologists Speak about Pieria, 54‒58. Katerini: NELE Pierias (in Greek, German summary).

- Bessios 2010

- Bessios, M. 2010. Pieridon Stefanos: Pydna, Methone and the Antiquities of North Pieria. Katerini: AFE Publications (in Greek).

- Bliquez 2015

- Bliquez, L. J. 2015. The Tools of Asclepius: Surgical Instruments in Greek and Roman Times. Leiden: Brill.

- Boyer, Bel, and Tranoy 1990

- Boyer, R., V. Bel, and L. Tranoy. 1990. “Decouverte de la tombe d’un oculiste à Lyon (fin du IIe s. après J.-C.): Instruments et coffrets avec collyres.” Gallia 47: 215‒49.

- Chrysostomou 2013

- Chrysostomou, A. 2013. Ancient Edessa: The Cemeteries. Volos: Hellenic Ministry of Culture (in Greek).

- Descamps-Lequime 2011

- Descamps-Lequime, S., ed. 2011. Au royaume d’Alexandre le Grand: La Macedoine antique. Paris: Louvre Museum.

- Giachi et al. 2013

- Giachi G., P. Pallechi, A. Romualdi, E. Ribechini, J. J. Luceiko, M. P. Colombini, and M. Mariotti Lippi. 2013. “Ingredients of a 2,000-y-old Medicine Revealed by Chemical, Mineralogical, and Botanical Investigation.” In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (January 22), 110.4: 1193–96. http://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1216776110/-/DCSupplemental

- Ignatiadou 2014a

- Ignatiadou, D. 2014. “The Stavroupolis Priest-warrior.” In The Greeks: Agamemnon to Alexander the Great, ed. M. Andreadaki-Vlazaki and A. Balaska, 388–401. Athens: Kapon.

- Ignatiadou 2014b

- Ignatiadou, D. 2014. “The Symbolic Krater.” In Le cratère à volutes: Destinations d’un vase de prestige entre Grecs et non Grecs, 43‒59. Cahiers du Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum (France) 2.

- Ignatiadou 2015

- Ignatiadou, D. 2015. “The Warrior Priest in Derveni Grave B Was a Healer Too.” Histoire, médecine et santé 8: 89‒113.

- Ignatiadou, forthcoming

- Ignatiadou, D. Forthcoming. “Burial Practices for Élite Macedonians with Cultic Duties.” In Constituer la tombe: Honorer les défunts en méditerranée hellénistique et romaine: Table ronde organisée par L’Écoloe française d’Athènes et le Centre d´étiudes alexandrines, Alexandrie, 29 octobre au 1er novembre 2014, ed. M. D. Nenna, W. van Andringa, and S. Huber.

- Katsifas et al., forthcoming

- Katsifas, C., D. Ignatiadou, N. Kantiranis, and G. A. Zachariadis. Forthcoming. “Metal Containers of the 4th century BC: Analysis of Their Composition and Contents.” In 9th Aegean Analytical Chemistry Days, 29 September‒3 October 2014, Chios, Greece.

- Koukouvou 1996

- Koukouvou, A. 1996. “Sidestreet of Ploutarchou Street (Building Block 305).” ADelt 51, B: 524 (in Greek).

- Pöhlmann 2013

- Pöhlmann, E. 2013. “Excavation, Dating and Content of Two Tombs in Daphne, Odos Olgas 53, Athens.” Greek and Roman Musical Studies 1: 7‒24.

- Romiopoulou 1973‒74

- Romiopoulou, K. 1973‒74. “Oreokastrou Street (Stavroupolis District).” ADelt 29, B 2: 693 (in Greek).

- Romiopoulou 1989

- Romiopoulou, K. 1989. “Closed Burial Contexts of the Late Classical Period from Thessaloniki.” In Φίλια Έπη εις Γεώργιον Ε. Μυλωνάν (Festschrift to George Mylonas), 3: 194‒218, plates 45‒58. Athens: Archaeologiki Etaireia (in Greek).

- Themelis and Touratsoglou 1997

- Themelis, P. G., and Y. P. Touratsoglou. 1997. The Derveni Tombs. Athens: TAP (in Greek, English summary).