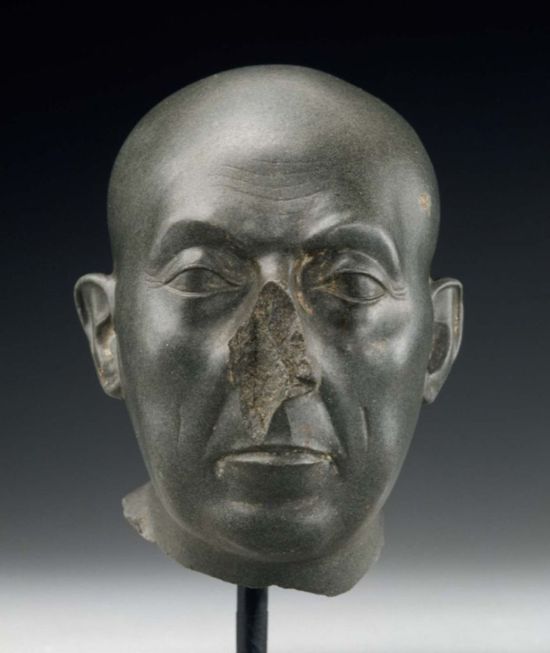

Head of a Priest, Egyptian or Ptolemaic, 400–300 BC, schist

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Henry Lillie Pierce Fund, 04.1749. Photograph © 2018 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Transcript

Female Narrator: These two beautiful green heads reveal a style of portraiture that Egyptian sculptors started using sometime between 664 and 332 BC. Instead of idealizing their subject, these portraits reveal the sitters’ imperfections.

Look first at the Boston Green Head, on the right.

Dr. Bob Bianchi: The image that we look at is characterized by a series of wrinkles that we term "signs of age."

Female Narrator: Robert Bianchi.

Dr. Bob Bianchi: You can see them in the forehead crow’s feet that you see at the outer corner of his eye, and we have these large furrows that run from the nose down to the mouth.

Female Narrator: Showing people in this more realistic way was a new development in Egyptian art.

Dr. Bob Bianchi: They are making an ideological statement that this is an elder member of society who is to be regarded as a man of influence, a man of power, a man of authority. We are not necessarily looking at a copy or a portrait of what this man looked like. We are looking rather at a statement that this individual has attained a specific point in his life and in his career.

Female Narrator: Look now at the Berlin head, on the left. Like the Boston head, it shows a man distinguished by visible wrinkles. But there’s a difference.

Dr. Bob Bianchi: In the Berlin green head, these signs of age are also visible in the profile views. In the Boston green head, if you were to take a magic saw and cut at the corner of the eyes all of the signs of age would disappear. They are not carried from the nose back to the ear.

Female Narrator: While Egyptian sculptors favored frontal views of their subjects, Greek sculptors showed their subjects in the round. So scholars think the Berlin head’s sculptor was influenced by Greek classical tradition: more evidence of how Egyptian and Greek art carried on a centuries-long dialogue.