|

|

|

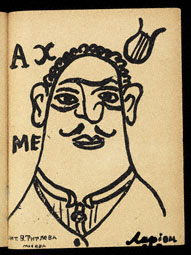

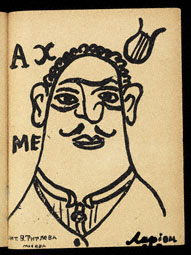

Portrait of Akhmet, Mikhail Larionov, in Worldbackwards (Mirskontsa), 1912

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tango with Cows takes its title from a book and poem by the Russian avant-garde poet Vasily Kamensky. The absurd image of farm animals dancing the tango evokes the clash in Russia between a primarily rural culture and a growing urban life. During the years spanning the revolutions of 1905 and 1917, Russia was in spiritual, social, and cultural crisis. The moral devastation of the failed 1905 revolution, the famines of 1911, the rapid influx of new technologies, and the outbreak of World War I led to disillusionment with modernity and a presentiment of apocalypse.

This exhibition explores the way Russian avant-garde poets and artists responded to this crisis through their book art. Often working collaboratively, poets and artists designed pages in which rubber-stamped zaum' or "transrational" poetry shared space with archaic and modern scripts, as well as with primitive and abstract imagery. The Russian avant-garde utilized such verbal and visual disruptions to convey humor, parody and an ambivalence about Russia's past, present, and future.

|

|

|

|

St. George the Dragonslayer (Sv. Georgii Pobedonosets), Natalia Goncharova, in Mystical Images of War: 14 Lithographs (Misticheskie obrazy voiny: 14 lithografii), 1914

|

|

|

The image at left of St. George the Dragonslayer opens the lithographic portfolio Mystical Images of War, which Natalia Goncharova completed soon after the outbreak of World War I. Goncharova weaves symbols from the bible, folk mythology, and history into her imagery of contemporary warfare. Representing Christ's victory over the Antichrist, the image of St. George sets the stage for the cycle's dualities of sacred and secular, past and present, and good and evil, which Goncharova accentuates by contrasting the white tones of the untreated paper with black inking.

The Russian avant-garde's perception of the primitive as the "magic fable of the old East" signified a loyalty to non-Western values. The East-West duality became a duality of time in which a rural past rich in ancient Christian and pagan traditions vied with a modern, urban present tainted by the materialism and decay of the West. This temporal anxiety is captured in the title of the book, Worldbackwards (download a PDF version, 41 pp., 5.48MB). The image at the top of this page shows the fictional character Akhmet, for whom Alexei Kruchenykh created a poem consisting of crude, irregular rhymes and an alogical language.

|

|

|

|

|

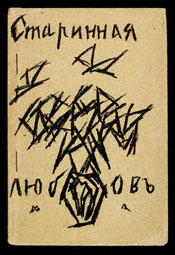

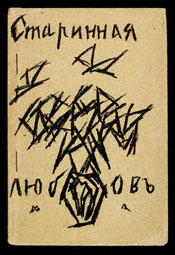

Cover of Old-Fashioned Love (Starinnaia liubov'), poetry by Alexei Kruchenykh and imagery by Mikhail Larionov, 1912

|

|

|

|

The Russian avant-garde challenged the lavish journals of Russian Symbolism by creating diminutive books such as A Trap for Judges (download a PDF version, 59 pp., 7.06MB)), an anthology printed on the reverse side of cheap wallpaper. Its comical, provocative title points to the Futurist contempt for literary critics and the press.

In 1912, Alexei Kruchenykh and Mikhail Larionov produced the first Russian avant-garde book, Old-Fashioned Love. Pictured at right, it is a primitive booklet daringly printed on cheap paper in a pocket-sized format. With this publication, Alexei Kruchenykh achieved a new unity of poetry and imagery by using the same lithographic process for both. His partnership with Mikhail Larionov yielded a remarkable cover in which a diamond-shaped vase containing a female form divides the title word liubov' (love) in half, and Cyrillic letters take on the triangular shapes of the vase, flowers, and butterflies. In the book's poetry, intentional misspellings coupled with images of provocative nudes lightly parody romantic love poetry.

|

|

|

|

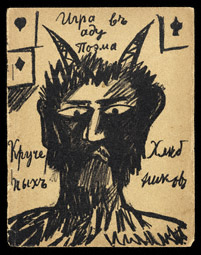

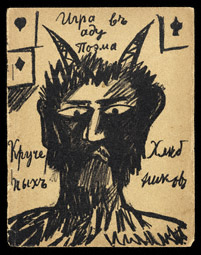

Cover of A Game in Hell: A Poem (Igra v adu: Poema), Natalia Goncharova, 1912

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From the Orthodox icon and popular lubok to Symbolist poetry and painting, the image of the devil was ubiquitous in Russian art and literature. The narrative poem in A Game in Hell, shown at left, concerns a card game between devils and sinners. The fixed stare and full-page presence of Goncharova's devil on the cover refers blasphemously to religious icons of Christ. Her sinister and absurd devils within play with multiple cultural types, including the archaic devil of Russian icons that pulls sinners to hell, and the parodic secular devil of the lubok, who is outwitted by man. By celebrating these shifting identities, the Futurists playfully conflate the worlds of the sacred and the secular. On page after page, whether silly, sinister, or grotesque, the Futurist devil assumes an ironic and provocative stance.

|

|

|

|

|

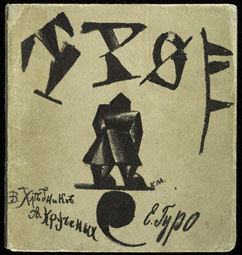

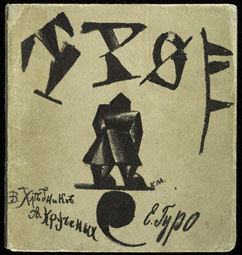

Cover of Threesome (Troe), Kazimir Malevich, 1913

|

|

Threesome, shown at right, was published nearly a year after the appearance in 1912 of "A Slap in the Face of Public Taste," the first manifesto of the Russian Futurists. The title Threesome refers to Kruchenykh, Khlebnikov, and Elena Guro. In the book we find Kruchenykh's manifesto "New Ways of the Word (the language of the future, death to Symbolism)" in which he uses the adjective zaumny (transrational) for the first time. According to Kruchenykh, "The word (and its components, the sounds) is not simply a truncated thought, not simply logic, it is first of all transrational." By moving beyond the mind, poets discovered the possibility of "totally new words."

In Kazimir Malevich's cover for the book the past confronts the future. He builds the bulky, black figure of a peasant worker out of triangles and cones that evoke a robot and transforms the Old-Church Slavonic lettering of his title into dynamic, triangular shapes.

|

|

|

|

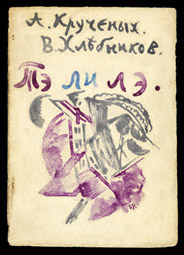

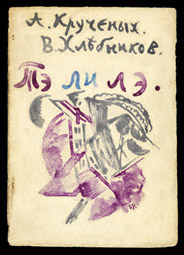

Cover of Te li le, Olga Rozanova, 1914

|

|

|

| Listen to poems from the book in Russian and English: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Russian avant-garde poets and artists applied the bold proclamations of their manifestos to books, such as Te li le, pictured at left, which explores the independent aural and graphic attributes of what they called the "word as such." Here, Olga Rozanova achieved a synthesis of painting, poetry, and sound. The rhyming sonorities of "te" and "le," highlighted in purple ink on the cover, draw us into her blend of handwritten words and decorative forms.

Another book in the exhibition, Explodity, serves as the centerpiece of this group of Futurist books that engage closely with the relationship between word, image, and sound (page through Explodity; opens new window).

|

|

|

|

|

Cover of Tango with Cows: Ferro-Concrete Poems (Tango s korovami: Zhelezobetonnye poemy), Vasily Kamensky, 1914

|

|

|

|

Tango with Cows, shown at right, offers a tour of Moscow's urban entertainment. In his "ferro-concrete" (reinforced concrete) poems, Vasily Kamensky replaced grammar and syntax with a spatial arrangement of words that celebrates concrete as a dynamic force in the invention of the modern city. The artists discarded customary book materials and printed Tango on cheap wallpaper as a parody of urban bourgeois taste. By juxtaposing the urban tango—an erotic Argentine dance that arrived in Russia in 1913 via Paris—with the cows of rural Russia, Kamensky captured the tension poets and artists felt between the recovery of a rural past and the allure of an urban present in creating their art of the future.

|

|

|

|

|