| Education | ||

| Exhibitions | ||

| Explore Art | ||

| Research and Conservation | ||

| Bookstore | ||

| Games | ||

| About the J. Paul Getty Museum | ||

| Public Programs | ||

| Museum Home

|

October 26, 2004–January 2, 2005 at the Getty Center

The Getty Research Institute (GRI) dedicates its resources and activities to advancing understanding of the visual arts and their history. This exhibition showcases the wide variety of primary documents and historical objects in the special collections of the Research Library at the GRI. An annual research theme at the GRI guides activities, including a residential scholars program, conferences, and lectures. The 2004–2005 theme, "Duration," is one of the inspirations for Past Presence. In language, time is expressed through tense, and this is the exhibition's main organizing principle. These objects cast light on how artists of the last four centuries have viewed the past, the present, and the future. In the engraving above, figures representing Time and Death hurl Antiquity—the art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome—to the ground. Painting and Sculpture recover the fragments under the direction of the gods of transmission, labor, and intellect. The artist suggests that the arts can preserve remnants of the ancient past. |

||||||

Past: Perfect and Imperfect The past tense can be expressed in the perfect and the imperfect. The past perfect signifies completion—for example, goals that had been achieved in the past. The imperfect is used for processes—for example, continual events, which were enduring as time was passing. The special collections of the GRI include many works by artists looking to the past for physical evidence of the perfect and the imperfect. |

||||||

In contrast to Piranesi's idealized presentation of the past (above), the buffeting effects of time—aging and decay—are evident in this stipple engraving from the first highlights catalog of the British Museum, which opened in 1753. In their quest to document historical remains accurately, authors and artists Jan and Andreas van Rymsdyk illustrate this decomposing skull (with a rib attached) and corroded sword found in the Tiber River. |

||||||

Collecting the Past Modern museum practice stems from earlier practices of imposing an order on collected objects. Early collectors often arranged objects for contemplation and study in personal cabinets of curiosity. This is the earliest known copperplate engraving of a curiosity cabinet. It shows the collection of natural and man-made wonders belonging to a prominent family of apothecaries in Verona. |

||||||

Present: Ephemeral and Eternal The present is ephemeral, momentary, and fleeting. In Peacock Zoomorphosis, an optical device from the mid-18th century, a peacock appears and disappears in a semi-cylindrical mirror above the distorted etching, depending on the viewer's position. |

||||||

Human perception may be ephemeral, but scientific truths based on perception are assumed to be eternal. These scientific principles are usually expressed in the present tense. Here, the concept that primary colors form the basis for all other colors is demonstrated by Philipp Otto Runge in his Farben-Kugel (Color-Sphere). The German romantic painter Runge was the first to devise a spherical coordination of primary and secondary hues with the value scale of light to dark. |

||||||

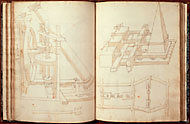

Future Perfect The future is often imagined in ideal terms. Drawings like this one by the Sienese architect, sculptor, and painter Francesco di Giorgio Martini and his workshop assistants portray ingenious devices and machines designed for architectural, agricultural, and military purposes. These designs imply that the future can be perfected by technology. |

||||||

The ideals of a 15th-century future seen above are echoed here in the 20th-century Architectural Fantasies of Iakov Chernikhov, a teacher of architecture during the Stalinist period of Soviet Russia in the 1930s. These powerful renditions of industrial might reflect the aspirations of the Soviet state. Chernikhov's book of "fantasies" is exemplary of a modernist genre practiced in the Soviet Union at the time. |

||||||