|

|

|

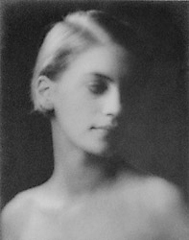

Portrait of Lee Miller, New York

Arnold Genthe

|

|

|

|

A rebellious and independent young woman, Miller (1907-1977) left her family home in Poughkeepsie, New York, at the age of 19 to enroll in the Art Students League. Shortly after, she pursued a modeling career in New York City. A model for several major magazines, Miller became friends with Vogue senior photographer Arnold Genthe, a German who had immigrated to the United States in the 1890s. Despite their 35-year age difference, Miller and Genthe reportedly adored one another and spent much time discussing art and culture during the late 1920s and 1930s. Genthe's study of her in a dreamlike reverie and apparently undressed casts her as the archetypal muse.

|

|

|

|

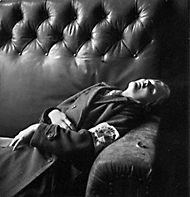

Marie-Berthe [Aurenche], Max Ernst, Lee Miller, and Man Ray, Paris

Man Ray

© 2002 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris

|

|

|

Financially independent from her work as a model, Miller persuaded her family to allow her to study and model in Paris. Soon after arriving there in 1929, she became Man Ray's studio assistant. She stayed with Man Ray for several years as his muse, apprentice, artistic collaborator, and lover. Some of Man Ray's most reproduced pictures were created between 1930 and 1932 with Miller's assistance. With Man Ray, Miller learned the craft of photography and was introduced to Surrealist artists, for whom social interaction was an important source of creativity. Here, Man Ray playfully photographed himself with Miller and two Surrealist friends.

|

|

|

|

|

Night and Day

Roland Penrose

© Antony Penrose, The Roland Penrose Collection, East Sussex, England 1999

|

|

|

|

Miller broke off her relationship with Man Ray in 1932 and left Paris for New York, where she established a portrait and advertising studio with her brother. Not long after, she married an Egyptian businessman and moved to Cairo, where she continued to make photographs on her own. During a visit to Paris, she was introduced to Surrealist artist Roland Penrose and soon became his muse and collaborator.

When Miller returned to Cairo after their first meeting, Penrose painted his new muse in an imaginary party costume. Her body is divided into three elements: her legs are earth, her torso and arms are air, and her face is fiery, like the sun. Her hands are in the forms of a dove and a swallow. In the background, one can make out a group of pyramids that signals Miller's whereabouts.

|

|

|

|

Portrait of Space

Lee Miller

© Lee Miller Archive 2002

|

|

|

|

|

|

While Miller was a muse to Penrose, Penrose was also a muse to Miller. When Miller returned to Egypt in 1937 after spending time with Penrose and his circle of Surrealist friends, her imagination was excited. The photographs she created after her visit move beyond the documentary and into the realm of the perceptual and the experimental. Made through a crooked frame embedded in a torn screen, this composition transforms an ordinary landscape into a strange and provocative abstraction.

|

|

|

|

|

Leipzig, Germany

Lee Miller

© The Trustees of the Lee Miller Archive, East Sussex, England 1999

|

|

In late 1942, at the age of 35, Miller received from the United States War Department a military identity card accrediting her as a war correspondent and later making her one of the only female combat photographers in the European war zones during World War II. Her photographs from the war fused her newfound documentary impulse with a Surrealist aesthetic developed during the 1930s and represent the culmination of her career in photography.

Miller was in Leipzig, Germany, when Hitler's Third Reich collapsed and many Nazis began to take their own lives. The city's mayor, Alfred Freybourg, and his wife and daughter honored a suicide pact together in the city hall. One of the first on the scene, Miller moved her camera close to the mayor's daughter, who is recorded in gentle, available light as though between dream and sleep, life and death, a state the Surrealist artists and poets greatly admired.

|

|

|

|

Nonconformist Chapel, Camden Town, London

Lee Miller

© The Trustees of the Lee Miller Archive, East Sussex, England 1999

|

|

|

The interplay between words and pictures was central to the Surrealist ideology. Here, Miller surely saw the irony between the name of the site (Nonconformist Chapel, with its advertisement for "Children's Sunday School") and the cascade of fallen bricks spilling out the door.

|

|

|

|

|

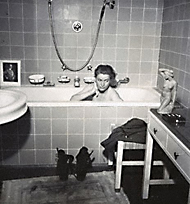

Lee Miller, Hitler's Residence, Munich, Germany

Lee Miller with David E. Scherman

|

|

In a collaborative effort with fellow photographer David Scherman, Miller posed in Hitler's personal bathroom the same day she photographed the liberation of Dachau. Poised and self-aware, Miller carefully constructed a stage set with a portrait of Hitler perched on the tub and her dirty boots at the foot of the bath. She raises her right arm in a gesture that mirrors the sculpture to her left.

|

|

|

|

Self-Portrait with Picasso, Paris

Lee Miller

© The Trustees of the Lee Miller Archive, East Sussex, England 1999

|

|

|

When Picasso saw Miller after the liberation of Paris, he remarked, "This is the first Allied soldier I have seen, and it's you!" Picasso's incredulity at seeing Miller in fatigues was likely spurred by his memories of her as the radiant, carefree model who sat for a portrait (on view in the exhibition) seven years earlier. Despite her smile in this self-portrait, Miller's experiences during the war, particularly the devastation at the concentration camps, are believed to have left her with an emotional wound that never fully healed. Robert Capa, another war correspondent, was present at this meeting and may have operated Miller's camera.

|

|