|

Beasts, both real and fantastic, swarm, creep, and scramble across the pages of manuscripts made in the Middle Ages (about 500–1500 A.D.). Animals were an essential aspect of almost every facet of life in this period. They formed the backbone of a farm-based economy, served as instantly recognizable visual symbols, and were imagined to be the fantastic inhabitants of unknown realms. This exhibition features a diverse assortment of these beasts from the colorful pages of illuminated manuscripts. The dragon was seen as the most powerful of God's creatures and was thought to lurk in hiding and then strangle its victims with its tail. This dragon from a bestiary (book of beasts) seems to scream as it prepares to attack its prey. Bestiaries presented stories about creatures both real and fanciful and were one of the most popular kinds of texts in the Middle Ages.

|

|

|

Animals played a dominant role in the everyday life of the Middle Ages. They were a source of food and clothing, farm labor, and transportation. They also provided the materials for the creation of books, from bird-quill pens to animal-skin parchment.

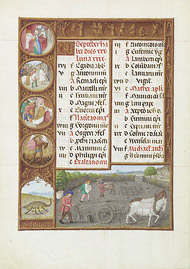

Medieval art reflects many activities involving animals, including depictions of farming and hunting. This page from an illustrated prayer book calendar shows heavy workhorses tilling the soil, straining against their harnesses as they pull a heavy plow. The facing page shows a bull being held by the horns for slaughter.

|

|

|

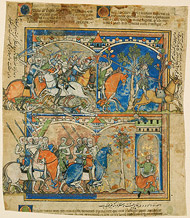

Violent clashes between horse-mounted soldiers took place often in the Middle Ages, an era of frequent war. This leaf depicts the frenzied conditions of a medieval battlefield, with enormous and powerful warhorses charging and clashing, sometimes even trampling soldiers underfoot.

These large warhorses were among the most prized possessions of knights and would have cost up to 800 times the price of a peasant's plow horse.

|

|

|

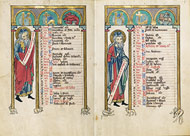

The fascination with animals seen in medieval art reflects the Christian belief that God made the creatures of the earth as symbols of his divine plan. Animals were also commonly understood to symbolize cultural values or ideas, such as loyalty or valor.

Animals often flanked medieval coats of arms, serving as symbols of their owners' virtues. French knight and treasury official Simon de Varie chose a greyhound, a symbol of devotion, for his heraldry—perhaps to highlight his loyalty to the French king. Court painter Jean Fouquet rendered the dog with astonishing realism, from the muscular tension in its hind legs to the texture of its short-haired, silky coat.

|

|

|

Many of the best-known constellations identified with animals are those associated with the 12 signs of the zodiac. Medieval devotional books often began with a calendar of the church year that featured illustrations of the zodiacal signs. The signs for Cancer (a crab-like creature) and Leo (a lion) appear prominently in the upper right corners of these two pages devoted to June and July.

The constellations were included on the pages of calendars because they were believed to influence the future.

|

|

|

In the Middle Ages, people imagined that exhilarating or even frightening animals lived beyond the known world. There were tales of giant, long-nosed creatures called elephants and of griffins with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. Artists let their imaginations run wild in depicting creatures of the unknown.

Medieval readers were fascinated by tales of mythological beasts from ancient Greece and Rome. The sea monster Scylla and a group of sirens appear in this text recounting the history of the world. Scylla's otherwise attractive form is deformed by two dragonlike, tooth-filled heads, while the sirens have chicken legs and huge wings. Both types of female creatures were meant to suggest that women can appear beautiful and enticing while also flaunting a beastly nature.

|

|

|

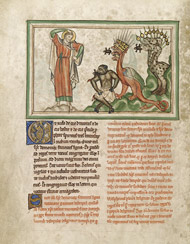

The Apocalypse, the Bible's description of the events leading to the Last Judgment, is filled with terrifying beasts.

In this image, an artist vividly imagined the three monsters described as coming to plague the world at the end of time: the apelike false prophet, whose intent is to mislead; the fearsome, seven-headed dragon, who will wage war on the faithful; and the spotted, seven-headed beast, who will receive the adoration of the earth.

Saint John stands at left, pulling on his forehead as if he must force his eyes open to witness the beastly horror.

|

|