|

|

|

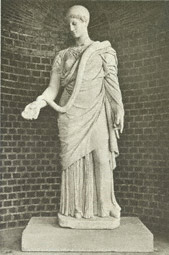

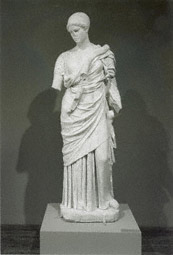

The Hope Hygieia (detail), Roman, A.D. 140–160. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, William Randolph Hearst Collection

|

|

This exhibition focuses on an over-life-size Roman marble statue of Hygieia, goddess of health. After being restored around 1800 and then de-restored in the 1970s, the figure was re-restored at the Getty Villa in 2006–2008.

The exhibition explores the statue's modern history and the evolving attitudes toward the restoration and display of classical sculpture on the part of collectors, curators, and conservators over the past two centuries.

The Hope Hygieia is on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

|

|

|

|

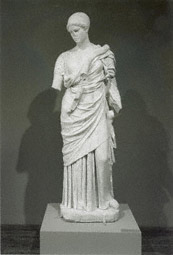

The Hope Hygieia as displayed at Melchet Court, the Hampshire residence of industrialist and art collector Alfred Mond. Mond owned the statue from 1917 to 1936. Photo courtesy of the Ashmole Archive, King's College London

|

|

|

The statue of Hygieia was found in 1797 at Ostia, the ancient port of Rome. It was missing its nose, inlaid eyes, right forearm, and left hand, as well as parts of the drapery and sections of the snake that curves around her body. (The snake is the goddess's symbol and refers to healing.) At the time, there was no question that the figure would be reconstructed using marble parts. For fragmentary ancient sculpture, this had been the customary treatment since the Renaissance.

The restoration work was probably carried out in an Italian studio before the statue was sold to Thomas Hope, for whom the figure is named. Hope was a British designer and member of the Society of Dilettanti, a circle of aristocratic patrons, antiquarians, artists, and architects dedicated to the study of the classical world. Hope's collection, which also included a statue of Athena found in the same excavations at Ostia, was dispersed through auction in 1917.

The Hope Hygieia and the Hope Athena were later owned by the American newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who donated them to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1950.

|

|

|

|

|

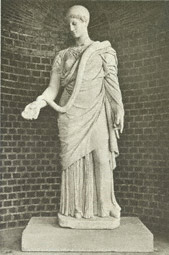

The Hope Hygieia as displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art between 1987 and 2006. Photograph © Museum Associates/LACMA

|

|

In the 1970s, a postmodern minimalist aesthetic held sway over the presentation of classical statues in public museums. Any modern intervention, no matter how reasonable, was considered a falsification of the original work.

The statue of Hygieia was stripped of its restorations at the newly opened J. Paul Getty Museum and displayed in a de-restored state, consisting only of ancient marble and plaster where structurally necessary.

The desired authenticity, however, was compromised by the lack of naturally broken surfaces, since the stone had been recut to accommodate the 19th-century additions. The missing parts now looked like amputations.

|

|

|

|

19th-century marble restorations alongside gray synthetic-resin replacements

|

|

|

Conservators and curators today understand that once an ancient sculpture is restored, its original archaeological state is irrecoverable. Modern restorations, moreover, are now seen as intrinsic to an object's history.

In 2006, at the request of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Getty conservators undertook the task of re-restoring the statue of Hygieia. The aim was to reconstruct its 19th-century appearance. Many of the parts removed in the 1970s had been preserved and could be reintegrated. The pieces, several of which are shown in this photograph, were carefully identified according to size and shape.

|

|

|

|

|

Replacement parts around the statue's left arm.

|

|

As the reconstruction went on, it became clear that some of the original restoration parts had been damaged or lost during the de-restoration process. Based on drawings and photographs of the statue before it was de-restored, replacements were sculpted from gray synthetic resin.

The parts were then reassembled using mechanical joints and soluble adhesives, which have minimal impact on the ancient marble.

Behind the figure's left arm, the area that had suffered the most damage, the conservators created a complex system of interlocking parts comprised of ancient fragments, 19th-century restorations, and newly formed replacements.

All the restoration work is fully reversible.

|

|

|

|

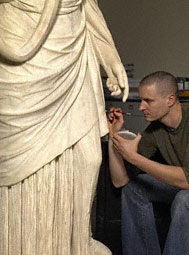

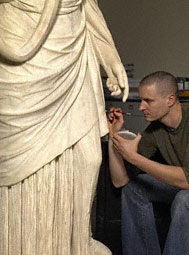

Getty conservator Erik Risser finishing in-painting of the Hope Hygieia.

|

|

|

In the last phase of re-restoration, the gaps between the reassembled parts were filled with a soluble paste of acrylic resin mixed with marble powder. These fills as well as the gray synthetic-resin additions were then painted to approximate the tone of the marble—a process called in-painting. The goal was to minimize, but not completely remove, the color differences between ancient and modern parts.

The statue of the Hope Hygieia is now visually unified, while the restorations remain evident on close inspection.

|

|