|

Like painters and draftsmen before them, photographers turned to the landscape as a source of inspiration after the invention of the medium was announced in 1839. Since then, changing artistic movements and continual technical advancements have provided opportunities for camera artists to approach the subject in diverse and imaginative ways.

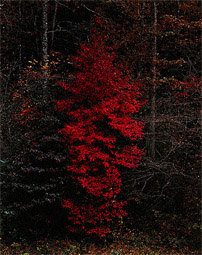

This exhibition, drawn exclusively from the Getty Museum's collection, brings together the work of more than 25 innovative photographers who have left their mark on the history of the genre. Representing key moments in the history of photography, the photographs in this exhibition are presented roughly chronologically to make the progression of aesthetic and technical developments apparent. Eliot Porter's portrait of a tree with brilliant red fall foliage, above, is meant to inspire preservation of the land for its beauty. Between the late 1930s, when the first popular color film was invented, and the mid-1970s, Porter dedicated himself to photographing nature. Remarkable for its subtle luminosity, his work was published in concert with conservation efforts and contributed to widespread acceptance of color photographs as art.

|

|

|

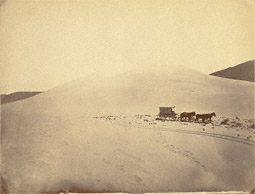

Timothy H. O'Sullivan honed his skills as a photographer during the American Civil War. In 1867 he joined the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, the first governmental survey of the West. His photographs were intended to provide information for expanding railroads and industry, yet they demonstrate his eye for poetic beauty.

Moving through the untamed Nevada wilderness, he stopped his mobile darkroom—a horse-drawn wagon—and photographed it amid sand dunes, creating a heroic image of exploration that is emblematic of the 19-century American identity.

|

|

|

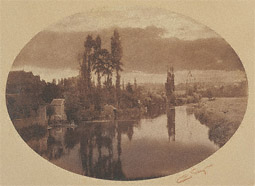

Early collodion-on-glass negatives, such as those Camille Silvy used to render this scene, were particularly sensitive to blue light, making them unsuitable for simultaneously capturing definition in land and sky. Silvy managed to achieve this synthesis of richly defined clouds and terrain by skillfully wedding two exposures and disguising any evidence of his intervention with delicate drawing and brushwork on the combination negative. The print exemplifies the tension between reality and artifice that is an integral part of the art of photography.

|

|

|

Alfred Stieglitz was a great promoter of Modernism in America and an advocate of photography as art. He began pointing his camera skyward in 1922. His images of evanescent clouds were meant to express his own fleeting emotional states and reflect the dynamism of a world in constant flux.

Originally Stieglitz titled these cloudscapes "songs of the sky," but he later came to call them "equivalents of my most profound life experience." The works focus on abstract qualities of proportion, rhythm, and harmony, presenting pure form as music for the eye.

|

|

|

Here Virginia Beahan and Laura McPhee delve into the landscape as a site of human history and conflict. With the High Sierra as a backdrop, rusty remnants of the Manzanar relocation camp, used to detain Japanese Americans during World War II, occupy the foreground.

In the middle ground stand the desiccated trunks of an orchard, probably the outgrowth of an 1860s settlement that was abandoned after the land's water was diverted in the 1920s to irrigate Los Angeles. That settlement, in turn, had uprooted a community of Paiute Indians, who had lived there for generations.

|

|