|

In the Middle Ages, hope mingled with fear concerning death and the afterlife, providing stirring subjects for manuscript illumination. Depictions of souls in paradise, the rewards of the blessed, and God's mercy reassured Christian audiences, while sometimes horrific illustrations of funerals, demons, and the punishment of the wicked prompted the pious to repent for their sins. At the core of visual devotion stood images of the crucified Christ, promising resurrection and eternal salvation.

This exhibition—which includes not only manuscripts but also printed books, a panel painting, stained glass and other media—explores medieval images that reflect imagined travels to the netherworld and attempts to map what awaited humankind beyond this earthly existence.

In Denise Poncher before a Vision of Death, the young owner of the manuscript is shown kneeling with her prayer book before a terrifying spectacle: the walking corpse of Death and three of his victims. The image likely served to remind the viewer that Death could arrive at any time and that prayer could prepare one's soul.

|

|

|

The morbid imagery found in late medieval prayer books sheds light on the intense preoccupation with matters of death. Lavish depictions of deathbed scenes, funeral rites, and the uncertain fate of departed souls focused attention on the viewer's own mortality and the transience of material wealth. Prayer cycles recorded in such manuscripts include the Office of the Dead, recited to ensure repose for the deceased and shorten their time in purgatory. The intimate scale of prayer books was appropriate, encouraging devout Christians to prepare themselves inwardly and contemplate death in solitude.

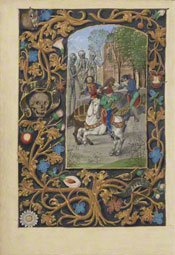

In The Three Living and the Three Dead, expressions of stark terror appear on the faces of noblemen on horseback as several corpses risen from the dead suddenly block their path. On the page's borders, disguised among golden leaves and beautiful flowers, a skull stares out at the viewer as a reminder that death is hidden in all worldly delights.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hell. Where is it? What does it look like? What horrors await the sinners there? In widely read stories such as The Visions of the Knight Tondal and The Divine Comedy, medieval audiences followed the main characters into the depths of the underworld, closely observing the infernal spectacle. These vivid accounts were frequently illustrated with terrifying images that exceeded even the most gruesome textual descriptions. The dialogue between the artistic imagination and a burgeoning scientific interest in the afterlife produced an idea of hell as a real, physical place infused with wild fantasies.

Originally written in the 1100s, The Visions of the Knight Tondal is the story of a wayward Irish knight whose dreamlike journey through hell and heaven teaches him the value of penitence. In the only known illustrated version of this tale, the Flemish artist Simon Marmion faithfully followed the text by depicting hell as a terrifying underground place with regions devoted to various sins—and punishments for them—and the awe-inspiring realms of heaven reserved for those who lived good and honest lives. The inventive images bring the story to life through atmospheric effects and expressive characters.

|

|

|

A divine moral order shaped the medieval understanding of time as a linear narrative from the Creation to the Last Judgment. In the face of God's final ruling over each soul, Christ's death on the cross to redeem the sins of mankind offered hope. In book illumination, panel painting, stained glass, and sculpture, artists turned Christian beliefs into arresting images of damnation and salvation intended to unsettle and motivate their audiences.

Viewers of Giuliano Amadei's colorful yet somber Crucifixion, a leaf from a missal used by the Pope in the Sistine Chapel, were intended to empathize with Christ's suffering and share in the historic event. As Christ dies on the cross, the lamenting figures of the Virgin Mary and Saint John stand on either side, while Mary Magdalene falls to her knees in grief. Christ's voluntary sacrifice at the Crucifixion was the defining moment of Christianity, making eternal salvation a possibility for true believers.

|

|