|

|

|

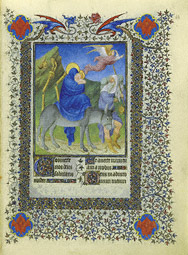

The Duke of Berry on a Journey (detail), Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

This exhibition presents more than 80 miniatures from the Belles Heures of the Duke of Berry, one of the supreme artistic treasures of French medieval manuscript illumination and a highlight of The Cloisters Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The book was recently unbound to allow for restoration and the production of a facsimile edition, offering a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to view all of its major miniatures in a single display.

The Belles Heures is a private prayer book commissioned in the early 1400s by John, the Duke of Berry (1340–1416), the son, brother, and uncle of three successive French kings. He appears twice in the Belles Heures, including the image at right, in which he rides a white horse toward a castle flying the flags of Burgundy.

The Belles Heures was illuminated by brothers Paul, Jean, and Herman de Limbourg, the leading northern European artists of their time. The book features 172 miniatures, a staggering quantity that reflects the duke's recognition of the illuminators' extraordinary talents.

This Web page presents selected masterpieces from the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

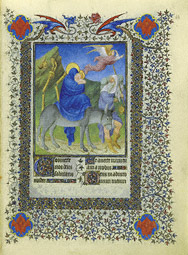

The Flight into Egypt, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Flight into Egypt

Like other medieval books of hours (prayer books for lay readers), the Belles Heures contains a series of devotions organized to foster prayer throughout the day.

The most important body of devotions, known as the Hours of the Virgin, consists of biblical Psalms along with hymns, prayers, and other readings. It is accompanied by scenes from the infancy of Christ.

In this scene, Joseph and Mary flee with the Christ child to Egypt in response to King Herod's threat to kill every male child in Bethlehem. Although Mary's face is hidden, her tender embrace of the child expresses her love. Joseph gazes back at his family in concern as he leads them onward.

|

|

|

|

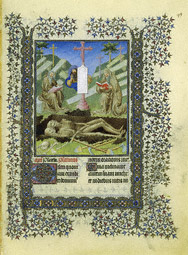

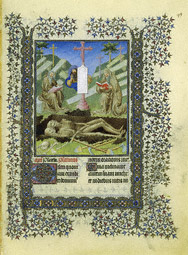

Corpses in an Open Grave, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

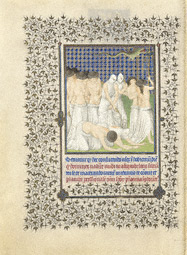

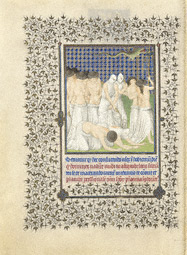

Corpses in an Open Grave

This mysterious cemetery scene accompanies the section of the Belles Heures known as the Office of the Dead, a standard feature of a book of hours. By praying the Office of the Dead on a daily basis, the living commemorated departed loved ones and sought to help them enter heaven more quickly. The text's value was heightened by the ubiquity of death in the Middle Ages, when disease, warfare, poor health care, and tremendously high infant mortality rates led to shorter lives.

In this illumination, a prophet emerges from behind the pink crucifix and points to the bodies in the grave. The corpses appear to not yet be buried, but they have decomposed nonetheless. Two men read or pray by the graveside. The meaning of the scene is unclear. Do the two corpses perhaps allude to the duke and his wife, thus reminding them of human frailty and their own mortality?

|

|

|

|

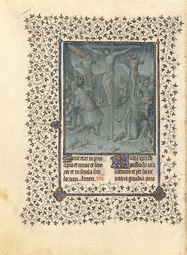

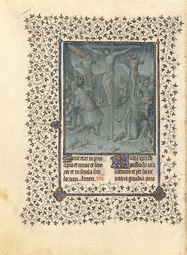

The Death of Christ, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Death of Christ

The four Gospel accounts of Christ's arrest, trial, Crucifixion, and death are known as the Passion of Christ. Beginning in the late 1300s the Passion assumed an increasingly central role in private devotion and the art that supported it. The Hours of the Passion is the most elaborate series of images in the Belles Heures.

This Passion miniature represents the climactic moment when, according to the Bible, the sky went dark at noon—the exact time of Christ's death.

The Limbourg brothers fully captured the dramatic and eerie scene as it is described in the text. According to the Gospel of Luke, the sun (at upper right) dimmed; the Gospel of Matthew describes graves opening and the dead rising, as seen here in the foreground.

|

|

|

|

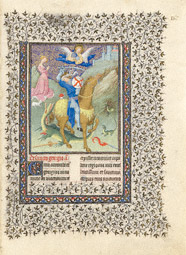

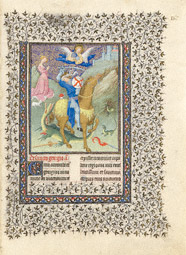

Saint George and the Dragon, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

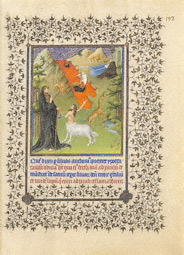

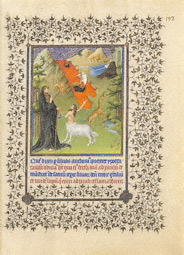

Saint George and the Dragon

Saints played a prominent role in medieval Christian devotional practice. The faithful regarded them as protectors, and they petitioned them for all kinds of assistance. The Belles Heures contains 35 suffrages (texts recited in honor of a particular saint), each illustrated with its

own miniature.

The chivalric ideals of the later Middle Ages are embodied in the beloved story in which Saint George, the patron of knighthood, saves a princess from a dragon. It also inspired countless works of art, including this masterpiece. The artists rendered the anatomy and movement of George's horse with great fidelity, while the depiction of the wholly imaginary dragon betrays less precision.

|

|

|

|

Saint Nicholas Saves Seafarers, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

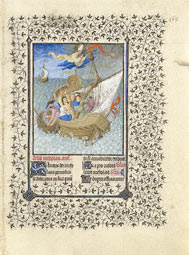

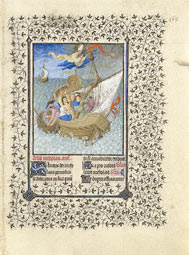

Saint Nicholas Saves Seafarers

Saint Nicholas was the patron saint of children,

sailors, unmarried women, merchants, and others. In this vivid scene he saves a sailing vessel in distress. The winds have shattered the mast and the frothy, roiling seas toss the large ship about. The Limbourg brothers conveyed the forces of nature along with the seafarers' varied responses to the threat.

The Limbourg brothers loved the challenge of representing the sea, and the Belles Heures contains a wealth of seafaring imagery. They even represented some traditionally land-based subjects with nautical settings.

|

|

|

|

Saint Anthony Receives Directions

from a Centaur, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saint Anthony Receives Directions

from a Centaur

Among the many saints depicted in the Belles Heures are Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Paul the Hermit. Known as the Desert Fathers, the two monks lived as hermits in abandoned buildings or caves, pursuing their faith through solitary lives of prayer, meditation, and manual labor. Anthony was widely venerated in the duke's day.

Despite his isolated existence, Anthony attracted other hermits who lived in loosely knit communities. Here a centaur shows Anthony the way from his hermitage to Paul's. The caption below the image states that both a centaur and a satyr helped Anthony, which may explain why the artists also gave the centaur goatlike hair and a satyr's cleft hooves.

|

|

|

|

Saint Catherine Tended by Angels, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

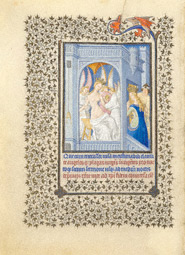

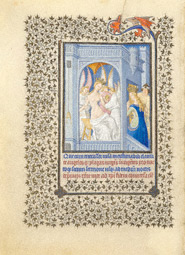

Saint Catherine Tended

by Angels

Saint Catherine of Alexandria was one of the most widely venerated saints of the Middle Ages. A series of miniatures in the Belles Heures recounts the story of Catherine's persecution for her Christian faith at the hands of the Roman emperor Maxentius.

This miniature depicts the Roman empress Faustina, who had heard of Catherine's troubles, sneaking into a prison to visit her. The caption below the image records that the empress witnessed angels tending to Catherine's wounds "in a wondrous light."

The illuminators express this light poetically through the radiance of both the young saint's nudity and the angels' white robes.

|

|

|

|

Procession of the Flagellants, Limbourg brothers, 1405–8/9

|

|

|

|

|

|

Procession of the Flagellants

Like all books of hours, the Belles Heures contains a litany—short appeals to a long list of individual saints for intercession. The texts and accompanying miniatures in this section of the book commemorate the time of Pope Gregory the Great (about 540–604), who instituted the litany in response to a bubonic plague.

Outbreaks of the plague were a cruel reality

of medieval life, in response to which men

went in procession "tormenting the flesh

in fasting and prayer and lamentation,"

as the caption on this image indicates. The Limbourgs gave this sorrowful ritual a strange beauty by depicting the flagellants in only a few colors and, following custom, bare to the

waist and wearing black hats.

This image reflects the Limbourg brothers' ability to depict anatomy, movement, posture, and expressive gesture with unsurpassed delicacy. Their art not only epitomizes the unrivaled artistic achievements of Parisian painting at the beginning of the 1400s, but also looks forward to the modern era in startling ways.

|

|

|

The exhibition was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in association with the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

All images on this page © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection.

|

|