|

|

|

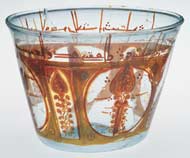

Tazza, Egypt or Syria, 1275–1325

|

|

|

|

Glass and ceramics are often united under the term "arts of fire" because of the heat required to create them. Glass is melted and shaped in a furnace, becoming rigid when it cools, while soft clay is shaped, dried, and then hardened in an oven called a kiln. They also share an ancient history because both are used to make functional products: jars for storage, vessels for dining, and beads and figurines of symbolic and ritual significance.

The technological development of both glass and ceramic decoration occurred in the Islamic Middle East between about 800 and 1350. These early techniques involving glazing, gilding, and painting emphasized the qualities of color and sparkle. By the 15th century, the active trade around the Mediterranean and the growth of a new affluent and urban European middle class in the late Middle Ages made these fancy tablewares popular art forms in Italy.

|

|

|

In about 950 glassmakers in Asia Minor and the Middle East created the first luxury glass since antiquity. Hundreds of years earlier, their homeland was under Roman rule and they either revived ancient Roman glass techniques—such as enamel painting and gilding—or rediscovered the techniques independently. Between 1100 and 1200 Egyptian and Syrian enameled and gilt glass became the finest in the world.

|

|

|

Italians learned how to apply enamels and gold to glass from Byzantine and Islamic craftspeople, who arrived in Venice by 1300. Italians copied Islamic ornament and also painted decorations that were more typical of the Italian Renaissance.

The glass pilgrim flask seen here depicts a circular medallion of Islamic origin, while the figures in a landscape on the flask below is a type of scene common to Italian Renaissance painting.

|

|

|

In addition to adapting techniques and ornamental elements from the Islamic world, Italians artists copied Eastern shapes for some of their glassware. Pilgrim flasks, which originally served as water canteens for travelers ("pilgrims"), are forms that came to Italy via the Middle East. The two seen here are purely decorative.

|

|

|

|

Bowl with Kufic Inscription, probably Egypt, 800–1000

|

|

|

About 800 Egyptian and Syrian glassmakers began using metallic stains for decoration, producing the kind of shimmering effect seen on this bowl. Potters in Iraq later adapted this staining technique to clay, creating ceramic luster, as seen on the dish below. Abul-Qasim, an important potter from Iran, wrote in 1301 that ceramic luster "reflects like red gold and shines like the light of the sun."

|

|

|

|

|

Deep Dish, Spain (Valencia region), about 1430

|

|

|

|

After Iraqi potters mastered the difficult luster technique on pottery, migrating craftspeople brought the technique to other parts of the Islamic world in the Middle East, North Africa, southern Italy, and Spain. In each area, potters mixed imported and local forms and decoration. Although specific styles and types differed from place to place, similar vibrant and dense surface decoration was popular throughout the Islamic world. The designs on the Spanish dish are examples of such surface ornament.

|

|

|

|

Pilgrim Flask, Syria or Egypt, 1400–1500

|

|

|

Decorative motifs became popular in one location and then in another, but how they were transmitted is unclear. Textiles, which were both highly valued and easily folded and transported, were an important means of disseminating decorative styles and motifs. Common elements include interlacing geometric patterns and plant imagery such as palmettes, scrolling foliage (which Europeans called arabesque because of its association with the Arab world), and the so-called tree of life.

In addition, each Islamic community, if not household, owned a copy of the Koran, the sacred text of Islam, and examples could have easily circulated outside the Islamic world. Early copies of the Koran were often written in Kufic script, an angular way of writing Arabic, which also appears on Islamic textiles and vessels, such as this pilgrim flask and the Egyptian glass bowl above.

|

|

|

|

|

Plate, Italy (Tuscany), about 1500–1520

|

|

Other Islamic motifs, including knotwork (a motif of interlacing lines) and the paired-animal pattern, became popular outside of the Islamic world through the circulation of portable art forms such as textiles, manuscripts, metalwork, and ceramics.

The knotwork seen in this Italian plate is similar to that seen on the Islamic pilgrim flask above. Italian craftspeople may have valued this decoration for its sophisticated patterning and distinctiveness.

|

|