25. Bronze Vessels and Related Instrumenta at Delphi: Remarks on Morphology, Provenance, and Chronology

- Valeria Meirano, Università degli Studi di Torino, Italy

Abstract

The circumstances under which the École Française d’Athènes conducted the chief excavation of the sanctuary of Delphi are well known: the so-called Grande Fouille represents a foundational page in the history of archaeological excavations in Greece during the nineteenth century. Between 1892 and 1903, French archaeologists brought to light the major part of the site (fig. 25.1), unveiling the ruins of the celebrated monuments described in the literary texts and contributing to the understanding of one of the most famous sanctuaries of the ancient world.1

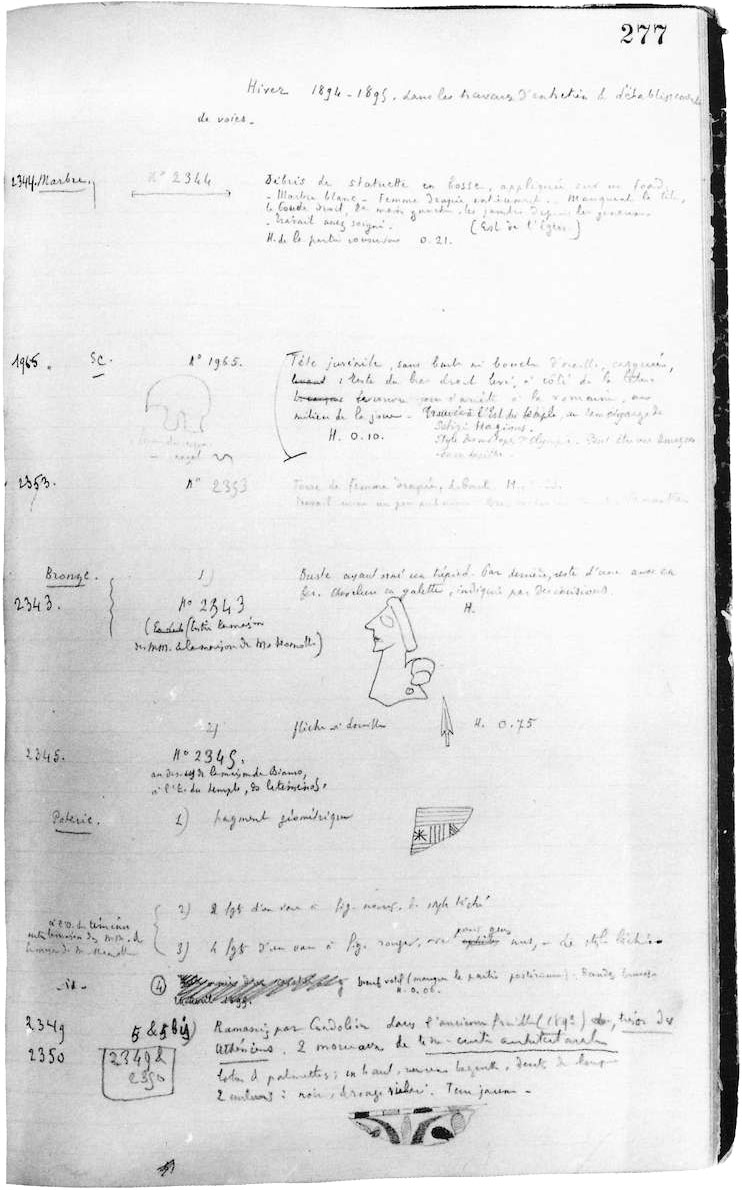

Topography, architecture, and sculpture were of course the main objectives, while the remaining evidence received far less attention during the excavations and in the subsequent studies. The Journal de la Grande Fouille, written during the decade of archaeological work, is proof of this attitude. Some pages, like the ones by Paul Perdrizet dealing with ceramics and small bronzes (fig. 25.2), represent exceptions in the general picture one gets from browsing the excavation journal.2

This approach toward exploration and the recording of data—aiming for the grand sweep of history and emphasizing rare treasures while discounting or ignoring smaller, more common artifacts—was widespread at the time and absolutely the norm in the nineteenth century. It inevitably caused the loss of a considerable number of pieces and of a wide body of information regarding the specific, original contexts and depositional conditions from which objects were retrieved. This paucity of information also concerns the association with other anathemata. It has hampered our understanding of various aspects related to the presence and use of these items in the sanctuary—for example, the crucial distinction between offerings and ritual devices—and made it difficult to identify assemblages of objects related to specific religious practices performed in the sacred area.

After the Grande Fouille, a consistent publication program started, including the small finds, which were published by Perdrizet himself in 1908.3 In this volume, which is still a fundamental work, a first selection of bronzes was documented. In the following decades, finds from new excavations were presented in preliminary reports in the Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique (BCH)4, while the majority of the contributions concerning the bronzes at Delphi were left to Claude Rolley. He was responsible for the systematic publication of the statuettes and the geometric tripods5 and the synthesis in the Guide de Delphes6 and was the author of numerous articles published mainly in the BCH.7

In the last few years, some specific categories of objects have seen systematic or at least partial publication, for example the helmets by Heide Frielinghaus8 and the seventh-century bronzes by Hélène Aurigny.9 The publication of a recent excavation in L’aire du pilier des Rhodiens by Jean Marc Luce (2008)10 provided fresh evidence concerning bronzes and their contextualization, an issue that previous documentation had made it difficult to approach at Delphi.11

Despite this progress, the vessels and the related instruments dating from Archaic to Roman times remained mostly unpublished, apart from some selective or preliminary studies. The aim of my work, which is still ongoing, is to put these disiecta membra and unpublished pieces in a wider perspective and to contribute to the understanding of offering choices, ritual practices performed in the sacred place, and the circulation of the metal objects.

Given the space constraints of this volume, I will expand only on some aspects of this broad topic. In light of the recent systematic survey, it is noteworthy that the dossier concerning the bronze vessels is meager compared with evidence coming from other contexts, for example Olympia and the Athenian acropolis, which is now the subject of reappraisal.12 The melting down of artifacts and the poor preservation of bronze due to the soil conditions at Delphi13 surely played a role in conservation (or lack thereof) and in determining the selection of the pieces to retrieve from the ground during past excavations.

In order to try to reestablish a reliable picture of the occurrence of bronze vases and instrumenta in the sanctuary, we should also take into account the data coming from epigraphic evidence and from literary sources, even on precious vessels. Herodotus mentions the six gold kraters offered by Gyges; the monumental silver krater on an iron stand by Glaukos of Chios, offered by Alyattes; and the golden cups and the two kraters offered by Croesus—one of silver and one of gold, attributed to Theodoros of Samos—which were positioned before the Temple of Apollo.14 Bronze vases, even monumental ones, must have been a very common sight among the offerings in the sacred area and even among the furniture and ritual tools: bronze tripods, for example, are less numerous than expected among the unearthed objects; nevertheless they play a crucial role in the imagery related to the sanctuary and are evoked during the whole life of the sacred place, long after the Geometric period. The presence of bronze phialai mesomphaloi as divine attributes and their use as ritual instruments are also widely reflected in official monuments and iconographies.15

Though it is not possible to present it in detail here, a general picture of the occurrence, morphology, and chronology of bronze vessels recovered from Delphi is now available. The quantitative indications are provisional and subject to change as the study progresses; in addition, a range of factors have yet to be taken into account in statistical analysis.16 Notwithstanding these difficulties, a quantitative approach is crucial and offers a fresh means of investigating the régime des offrandes—and their meaning—in the sacred context.17

As previously stated, contextualization is problematic at Delphi, but nevertheless it rewards study. Although the majority of the finds of known provenance come from the sanctuaries of Apollo and Athena at Marmaria, some evidence was retrieved from funerary and domestic contexts as well. In general, the number of bronze vases and instruments dramatically decreases starting from the fourth century BC. Among the pieces of known provenance, the Hellenistic and later ones mainly come from profane contexts, a sign of the progressive change in ritual practice and offering strategies.

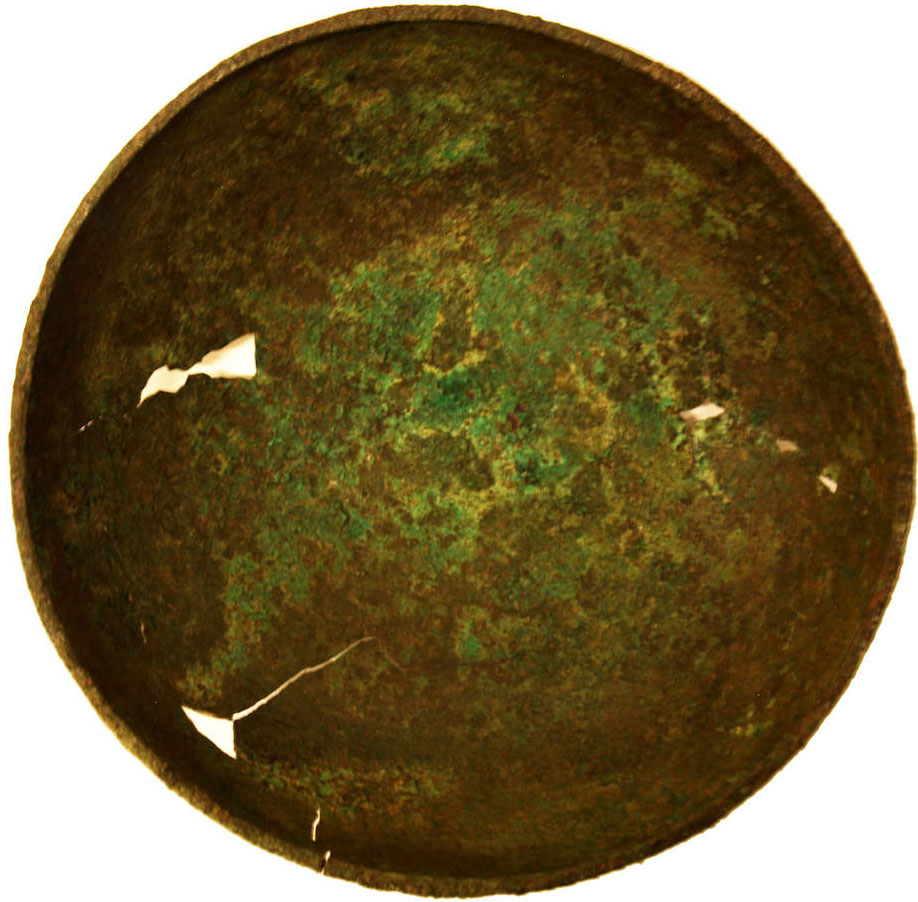

Open shapes are predominant. Among them we find the drinking vessels and the libation vases par excellence, phialai mesompaloi, both in the “plain” and in the “lotus-bowl” versions, together with large, deep bowls (fig. 25.3). Kantharoi, kylikes, and other handled cups, skyphoi, and mugs are far less attested, while handles are the only surviving parts of paterae.

Various types of large and medium-sized basins are widely documented, as well as deinoi with their characteristic profile. I could identify the presence of at least two fragments pertaining to basins with embossed rims, a shape that was not attested previously at Delphi.18 These vessels provide clues to the attendance at the sanctuary, or rather to the circulation of bronze objects. The shape of these basins is of certain Etruscan origin and the majority of the specimens known so far come from the Tyrrhenian area and from the central Italian peninsula. Nevertheless, the vessel type is widely documented, from the barbarian contexts of central-western Europe to central-eastern Mediterranean. In Greece, these basins are definitely rare and occur in only a few sites, namely sanctuaries, including Olympia.19 In the last few decades, the version bearing a single row of bosses—like the specimens attested at Delphi—has been noticed in eastern Sicily, where these vessels mainly occur in graves as funerary receptacles:20 the proposal of local production has been advanced, based on technical and morphological features. In Southern Italy as well, the discovery of a homogeneous group of basins of this type in Greek contexts—mostly coming from the sanctuary of Scrimbia at Hipponion in southern Calabria21—showing close affinities with the Sicilian group, corroborates the hypothesis of a western Greek manufacture inspired by Etruscan prototypes. Technical details would in some cases support the Greek colonial provenance of some of the basins found in Greece. In the case of the fragments from Delphi, which do not preserve their entire profile, it would be difficult to ascertain their origin, apart from their western provenance: a south Italian or Sicilian production remains conjectural, though highly probable.

Kraters are attested by a few ascertained fragments, a pale echo of the presence of this shape in the sanctuary as recorded by the ancient sources. Among them, some can be ascribed to volute specimens, which are notoriously rare.22

A few pieces attest to the presence of small forms like pyxides, bombylioi, bottles, and aryballoi, among which are also bronze disk rims that attached to small vases of perishable material, and one rare figured specimen in the shape of a tortoise.

Large closed shapes, which can be recognized as hydriai, olpai, and oinochoai, are mainly documented by fragments or miniature versions, with some exceptions. One is the known hydria dating to the mid-fifth century BC, which served as a cinerary urn in a tomb unearthed during the excavations for the building of the new museum.23 Another example is a small, refined trefoil oinochoe, which can be compared with Macedonian specimens of the fourth century BC.24

As expected, the number of handles is large. Some are figured specimens with stylistic features that significantly contribute to the identification of production areas and to the definition of circulation dynamics of bronze objects. The various types of attested vertical handles suggest a wider range of closed shapes in comparison to what is documented by other morphological forms (fig. 25.4).

Refined horizontal handles, sometimes with decorative elements, as well as figured appliqués, support the presence of large vases like podanipteres or kraters, which are also possibly echoed by fragments of stands with lion paws.25 Some small tripods were connected to exaleiptra and to other small or miniature shapes (figs. 25.5a-b).

Among the instrumenta, lamps are attested especially in the Late Hellenistic and Roman times, when we find some figured specimens, like one in the shape of a grotesque figure (fig. 25.6).26

a

a

b

b

Finally, we find a group of “vertical” instruments, namely candelabra, kottaboi, and other such articles. Some pieces—in particular a few curved arms with decorated finials showing serpent heads or floral motifs—are probably to be interpreted as parts of utensil stands, a rare class that is better known in western Greece, thanks to some specimens from Epizephyrian Lokroi (Locri, in Calabria).27

Research on Delphic bronze vessels and instruments also seeks to record and explain the detectable traces of actions made during the sacred rituals and the consecrations of offerings, in order to better understand the behaviors performed by devotees and priests in the sacred precinct. The “partial” offering of metal objects has already been demonstrated in various Greek sacred contexts, especially regarding vases and weapons.28 Modifications of and deliberate damage to bronze objects by breaking, bending, piercing, mutilating, and so on are known at many necropoleis and sanctuaries, including Delphi, where this practice is attested on some helmet cheek-pieces.29

Acknowledgments

The research on metal vessels and related instrumenta at Delphi is conducted in the frame of the Contrat Quinquennal of the École Française d’Athènes under the auspices of the local Ephoria. I would also like to acknowledge the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation in Athens and the Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene for their support and the research facilities provided.

Notes

- For the Grande Fouille and its scientific and political implications, see École Française d’Athènes 1992. ↩

- For the degree of scrutiny by Perdrizet in observing and documenting the small finds, see Jacquemin 1992, 156–57; Meirano 2016. ↩

- Perdrizet 1908. ↩

- For example, Hansen 1960; Rolley and Rougemont 1973; Rolley 1999. ↩

- Rolley 1969 and 1977. ↩

- Rolley 1991a. ↩

- For example, Masson and Rolley 1971; Rolley 2002; for the archaeometric program on geometric, oriental, and orientalizing bronzes, including samples taken from objects from Delphi, see Magou et al. 1991 and previous contributions in the BCH. ↩

- Frielinghaus 2007. ↩

- Aurigny 2010 and 2011. ↩

- Luce 2008. ↩

- Meirano, forthcoming (a), and Meirano 2016. ↩

- Tarditi 2016a; Tarditi 2016b; and her paper in this volume. ↩

- See, for example, Rolley 1991b, 187. ↩

- Herodotus 1.14, 1.25, 1.51. ↩

- Meirano 2016. ↩

- The bronze objects are particularly fragmentary at Delphi; they are often badly preserved and in some cases in need of conservation. These circumstances do not facilitate the identification of the “minimum number of individuals”: see Meirano, forthcoming (a). ↩

- See, for example, the remarks about the occurrence of various kinds of weapons in the sanctuary of Olympia—and their implications—recently made by Graells i Fabregat (2016, 149 and fig. 1). ↩

- Meirano, forthcoming (b). ↩

- For a review of the find contexts of embossed rim basins in Greece, with further bibliography, see Meirano 2004, 306; Meirano 2012, 96; Baitinger 2013, 251–52. ↩

- Among the numerous contributions devoted to this topic, see Albanese 1979; Albanese Procelli 1980–81 and 1985. ↩

- Meirano 2004; 2005, 47–48; 2012, 97–102; 2014. In the same region, a few specimens come from the Greek colonies of Lokroi, Rhegion, and Kroton: see Meirano 2004, 306. ↩

- See Rolley 2003, 102–3, n. 15, figs. 59–61. For the particular status of the volute krater as a “prestige vase,” especially in the metal version, also see: de La Genière 2014. ↩

- Rolley 1991a, 175, n. 43. ↩

- For example, see Siganidou 1979, 40, n. 35, plate 9 (from grave 1 of the Kozani necropolis). ↩

- For example, Rolley and Rougemont 1973, 515–16, n. 5, figs. 21–22; Rolley 1991a, 165, n. 32. ↩

- Rolley 1991a, 179, n. 49. ↩

- Meirano 2002. ↩

- For the practice of selective or partial dedication of metal vessels in western Greek sacred contexts, see Meirano 2014, 34; see also Meirano 2016. Concerning the separated offering of cuirass breastplates and back-plates at Olympia and in other Greek sanctuaries, see Graells i Fabregat 2016, 152–53. ↩

- Frielinghaus 2007, 147. See Meirano, forthcoming (a) and Meirano 2016 for further bibliography on this practice, also regarding mirrors, vases, and other types of weapons in Greek sanctuaries of southern Italy. For the deliberate damage to bronze objects at Olympia, see Frielinghaus 2006; Frielinghaus 2011, 185–200; about this practice regarding bronze cuirasses at Olympia, the destruction steps, and possible meanings, see Graells i Fabregat 2016. ↩

Bibliography

- Albanese 1979

- Albanese, R. M. 1979. “Bacini bronzei con orlo perlato del Museo Archeologico di Siracusa.” BdA: 1–20.

- Albanese Procelli 1980–81

- Albanese Procelli, R. M. 1980–81. “Intervento.” Kokalos 26–27: 139–48.

- Albanese Procelli 1985

- Albanese Procelli, R. M. 1985. “Considerazioni sulla distribuzione dei bacini bronzei in area tirrenica e in Sicilia.” In Il commercio etrusco arcaico: Atti dell’incontro di studio, Salerno 5–7 dicembre 1983 (QArchEtr 9), 179–206. Rome: CNR.

- Aurigny 2010

- Aurigny, H. 2010. “Delphes au VIIe siècle.” In La Méditerranée au VIIe siècle av. J.-C.: Essais d’analyses archéologiques (Travaux de la maison René Ginouvès 7), ed. R. Etienne, 234–49. Paris: de Boccard.

- Aurigny 2011

- Aurigny, H. 2011. “Le sanctuaire de Delphes et ses relations extérieures au VIIème siècle av J.-C.: Le témoignage des offrandes.” In Delphes, sa cité, sa région, ses relations internationales: Actes de la Table Ronde organisée les 24 et 25 septembre 2010 (Pallas: Revue d’études antiques 87), ed. J. M. Luce, 151–68. Toulouse: Presses Universitaire du Mirail.

- Baitinger 2013

- Baitinger, H. 2013. Sizilisch-Unteritalische Funde in Griechischen Heiligtümern: Ein Beitrag zu den Votivsitten in Griechenland in spätgeometrischer und archaïscher Zeit. Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums.

- École Française d’Athènes 1991

- École Française d’Athènes. 1991. Guide de Delphes: Le Musée. Paris: de Boccard.

- École Française d’Athènes 1992

- École Française d’Athènes. 1992. La redécouverte de Delphes. Paris: de Boccard.

- Frielinghaus 2006

- Frielinghaus, H. 2006. “Deliberate Damage to Bronze Votives in Olympia during Archaic and Early Classical Times.” In Common Ground: Archaeology, Art, Science and Humanities, Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Boston, August 23–26, 2003, ed. C. C. Mattusch, A. A. Donohue, and A. Brauer, 36–38. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Frielinghaus 2007

- Frielinghaus, H. 2007. “Die Helme von Delphi.” BCH 131: 139–85.

- Frielinghaus 2011

- Frielinghaus, H. 2011. Die Helme von Olympia: Ein Beitrag zu Waffenweihungen in Griechischen Heiligtümern. Olympische Forschungen 33. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter.

- Graells i Fabregat 2016

- Graells i Fabregat, R. 2016. “Destruction of Votive Offerings in Greek Sanctuaries: The Case of the Cuirasses of Olympia.” In Materielle Kultur und Identität im Spannungsfeld zwischen mediterraner Welt und Mitteleuropa: Akten der Internationalen Tagung am Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseum, Mainz, 22.–24. Oktober 2014, ed. H. Baitinger, 149–60. Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums.

- Hansen 1960

- Hansen, E. 1960. “Les abords du trésor de Siphnos à Delphes.” BCH 84: 387–433.

- Jacquemin 1992

- Jacquemin, A. 1992. “En feuilletant le Journal de la Grande Fouille.” In École Française d’Athènes 1992, 149–79.

- La Genière 2014

- La Genière, J. de, ed. 2014. Le cratère à volutes: Destinations d’un vase de prestige entre Grecs et non-Grecs: Actes du Colloque international du Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, Paris, 26–27 octobre 2012. Cahiers du Corpus vasorum antiquorum (France) 2. Paris: de Boccard.

- Luce 2008

- Luce, J.-M., ed. 2008. L’aire du Pilier des Rhodiens (fouille 1990–1992) à la frontière du profane et du sacré. Fouilles de Delphes 2; Topographie et architecture 13. Athènes-Paris: de Boccard.

- Magou et al. 1991

- Magou, E., M. Pernot, and C. Rolley. 1991. “Bronzes orientaux et orientalisants: Analyses complémentaires.” BCH 115: 560–77.

- Masson and Rolley 1971

- Masson, O., and C. Rolley. 1971. “Un bronze de Delphes à inscription chypriote syllabique.” BCH 95: 295–304.

- Meirano 2002

- Meirano, V. 2002. “Utensil stands da Locri Epizefiri: Nuovi dati dalla necropoli di Lucifero e dal santuario di Mannella.” In I Bronzi antichi: produzione e tecnologia: Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale sui Bronzi Antichi, Grado-Aquileia 22–26 maggio 2001, ed. A. Giumlia Mair, 117–26. Montagnac: Éditions Monique Mergoil.

- Meirano 2004

- Meirano, V. 2004. “Bacili ad orlo perlinato: nuovi dati dai contesti sacri della Calabria meridionale.” In The Antique Bronzes: Typology, Chronology and Authenticity: Acta of the 16th International Congress on Antique Bronzes, Bucharest, May 26th–31st, 2003, ed. C. Muşeteanu, 305–17. Bucharest: Editura Cetatea de Scaun.

- Meirano 2005

- Meirano, V. 2005. “Vasellame ed instrumentum metallico nei santuari di Locri/Mannella, Hipponion/Scrimbia e Medma/Calderazzo.” In Lo spazio del rito: Santuari e culti in Italia meridionale tra indigeni e Greci: Atti delle giornate di studio, Matera 28–29/6/2002, ed. M. L. Nava and M. Osanna (Siris: Studi e ricerche della Scuola di Specializzaizone in Beni archeologici di Matera, Suppl. 1), 43–53.

- Meirano 2012

- Meirano V. 2012. “Contributo alla conoscenza del vasellame bronzeo di età arcaica in Calabria meridionale: I bacili ad orlo perlinato.” In Vincenzo Nusdeo sulle tracce della storia: Studi in onore di Vincenzo Nusdeo nel decennale della scomparsa, ed. M. D’Andrea, 93–107. Vibo Valentia: AdHoc Edizioni.

- Meirano 2014

- Meirano, V. 2014. “Vasi, strumenti e altri oggetti: Offerte in metallo e pratiche rituali nei santuari greci della Calabria meridionale.” In Le spose e gli eroi: Offerte in bronzo e in ferro dai santuari e dalle necropoli della Calabria greca, ed. M. T. Iannelli and C. Sabbione, 32–38. Vibo Valentia: AdHoc Edizioni.

- Meirano 2016

- Meirano, V. 2016. “Bronze phialai mesomphaloi in Context: Some Recent and Older (Revisited) Case-studies.” In Greek and Roman Bronzes from the Eastern Mediterranean: Acta of the XVIIth International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, Izmir (Turkey) 2016, ed. A. Giumlia Mair and C. C. Mattusch, 79–86. Autun: Editions Mergoil.

- Meirano, forthcoming (a)

- Meirano, V. Forthcoming. “Étude des vases en métal et des instruments apparentés de Delphes, du VIème s. av. n. è. à l’époque romaine: Rapport 2014–2015.” BCH 139–40.2.

- Meirano, forthcoming (b)

- Meirano, V. Forthcoming. “Bassins à rebord perlé à Delphes.” In preparation.

- Perdrizet 1908

- Perdrizet, P. 1908. Monuments figurés, petits bronzes, terres cuites, antiquités diverses. Fouilles de Delphes 5; Monuments figurés 1. Paris: Albert Fontemoing.

- Rolley 1969

- Rolley, C. 1969. Le statuettes de bronze. Fouilles de Delphes 5; Monuments figurés 2. Paris: de Boccard.

- Rolley 1977

- Rolley, C. 1977. Les trépieds à cuve clouée. Fouilles de Delphes 5; Monuments figurés 3. Paris: de Boccard.

- Rolley 1991a

- Rolley, C. 1991. “Les bronzes: Statuettes et objets divers.” In Guide de Delphes: Le Musée, 139–79. Paris: École Française d’Athènes.

- Rolley 1991b

- Rolley, C. 1991. “Statues de bronze: fragments divers.” In Guide de Delphes: Le Musée, 187–89. Paris: École Française d’Athènes.

- Rolley 1999

- Rolley, C. 1999. “Delphes: Les bronzes.” BCH 123: 465–67.

- Rolley 2002

- Rolley, C. 2002. “Le travail du bronze à Delphes.” BCH 126: 41–54.

- Rolley 2003

- Rolley, C., ed. 2003. La tombe princière de Vix. Paris: Picard.

- Rolley and Rougemont 1973

- Rolley, C., and G. Rougemont. 1973. “Sondage à l’Est du sanctuaire d’Apollon: Catalogue des objets en métal.” BCH 97: 512–25.

- Siganidou 1979

- Siganidou, M. 1979. “Western Macedonia.” In Treasures of Ancient Macedonia, ed. K. Ninou, 38–47. Athens: Archaeological Museum of Thessalonike.

- Tarditi 2016a

- Tarditi, C. 2016. “The Athenian Archaic Bronze Vessel Production: New Evidence from Old Excavations.” In Greek and Roman Bronzes from the Eastern Mediterranean: Acta of the XVIIth International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, Izmir, ed. A. Giumlia Mair and C. C. Mattusch, 49–58. Autun: Editions Mergoil.

- Tarditi 2016b

- Tarditi, C. 2016. Bronze Vessels from the Acropolis: Style and Decoration in Athenian Production between the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BC. Rome: Edizioni Quasar.