22. The Portrait of a Hellenistic Ruler in the National Museum of Iran

- Gunvor Lindström, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Berlin

Abstract

Discovery in 1935 in Ancient Elymais

The portrait head of a Hellenistic ruler (fig. 22.1) was discovered more than eighty years ago in Kal-e Chendar in the valley of Shami, north of Izeh in present-day Khuzistan (ancient Elymais). It is often stated that Sir Aurel Stein (1862–1943), the famous Hungarian-British explorer, excavated the portrait. In fact, it was found accidentally in the course of construction work, shortly before Stein arrived at the site.1 In 1935 local seminomadic Bakhtiaris had been obliged to settle down, and as they dug the foundations for a dwelling they discovered fragments of ancient statues made of bronze and marble. Of these, the so-called Parthian nobleman—a nearly complete statue of a man in Parthian dress, some 2 meters (6 ½ ft.) high—is the most well known.2 When the military governor of the district came to learn of the discoveries, he ordered that the site be left undisturbed and transported all the finds to his house at Malamir (modern Izeh). About six months later, Stein visited the region during his Fourth Expedition into Iran. He saw the finds at the governor’s house, took some photographs of the statues, and decided to visit the place of their discovery.

Excavations by Sir Aurel Stein in 1936

Stein excavated at Kal-e Chendar for six days between January 28 and February 3, 1936.3 During this period, he conducted a brief survey of the whole site and opened a trench in the area where the sculptures were found. He found the remains of a quadrangular enclosure, about 12.5 by 23.5 meters (41 x 77 ft.), with an altar built of burnt bricks in the center. These suggested to Stein a shrine with veranda-like halls along the walls and a central area left open to the sky. The structural remains are documented in a sketch plan, with marks for the findspots of the objects recovered during the archaeological investigations and for the earlier excavated sculptural fragments, as reported by the local villagers.4 Altogether, fragments of seven large-scale bronze sculptures and six smaller figures of bronze and marble were found. Based on the presumed dating of the sculptures, Stein wrote, “it has proved a shrine where local worship, continued into Parthian times, had in a syncretistic fashion common to the Near East combined Hellenistic cult of Greek divinities with the worship of deified royal personages, perhaps from Alexander the Great down to Iranian chiefs for us nameless.”5

Recent Investigations at Kal-e Chendar by the Iranian-Italian Mission

Despite these extraordinary discoveries, Kal-e Chendar soon fell into oblivion, at least among archaeologists.6 However, in 2012 the Iranian-Italian Joint Expedition in Khuzistan carried out a new survey and started archaeological investigations.7 According to their preliminary results, the site consisted of at least three monumental terraces. The photographs taken by Stein in 1936 enabled the archaeologists to determine the approximate spot where Stein excavated, which is now covered over and cultivated. The Stein trench is at a peripheral part of the largest terrace, which extends for more than 6,000 square meters (65,000 sq. ft.). Therefore, the discovered enclosure was hardly the main building of the sanctuary. Rather, the focal point was a large temple, which is attested so far only by column drums and blocks of ancient masonry, scattered on the surface or reused in the walls of modern houses. The sculptures found in 1935 and 1936 most likely belong to the presumed temple, and their number and quality indicate that it must have been one of the most renowned religious places of ancient Elymais. Given the style and date of the ruler portrait in question, the sanctuary must have been established already in Hellenistic times.

The Head

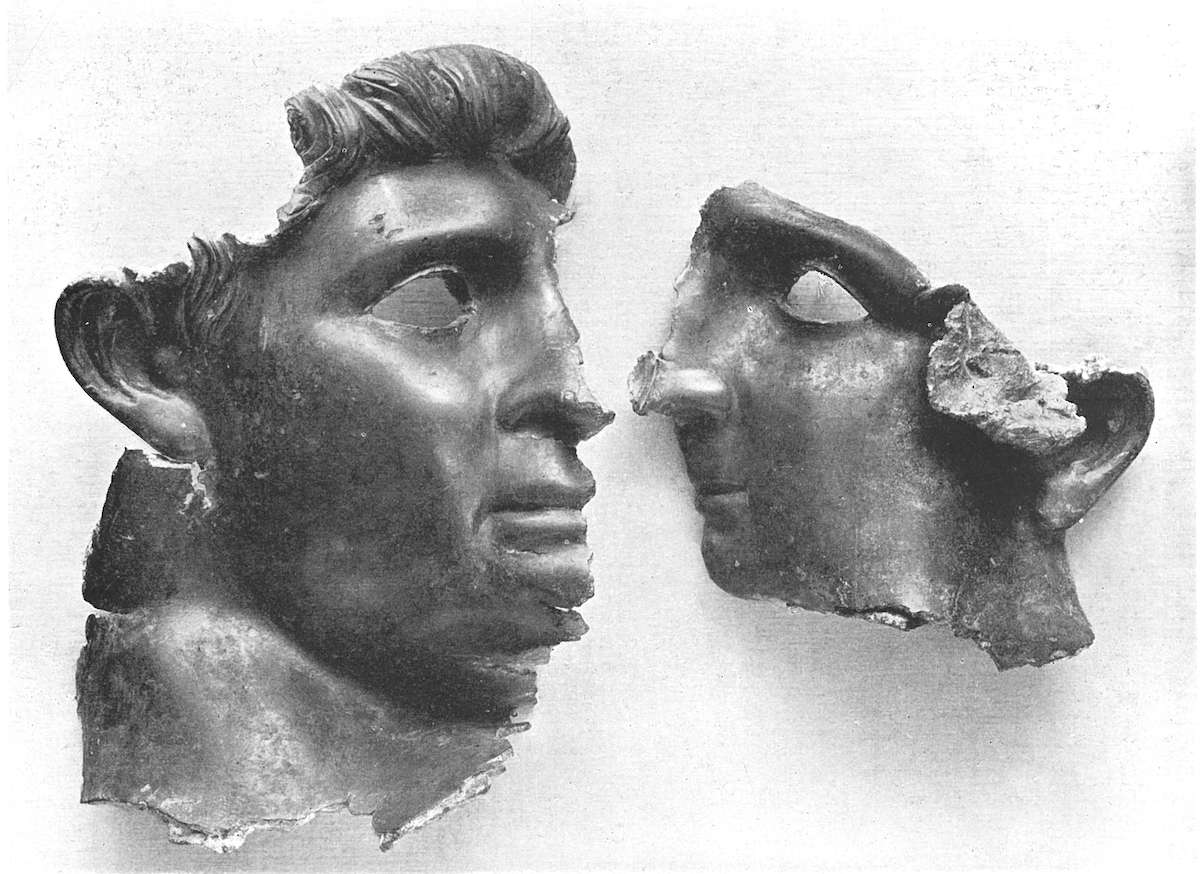

The head was found in two pieces, obviously severed in antiquity. The first published photo shows both fragments lying on their sides, juxtaposed (fig. 22.2). Although Stein noted that the two parts fit together, the side views of the faces differ sufficiently that some scholars assume that they represent two different portraits.8 In any case, for aesthetic and museum reasons the two parts were fixed together sometime in the 1960s and the join was covered with epoxy. The fragments compose a clean-shaven face with both ears, parts of the hair, and the front part of the neck, which is bent forward. The upper and posterior parts of the head were detached from the face and are not preserved.9 Although there is a deep dent in the right cheek, the appearance of the right side is still vigorous. The left side is quite different: the jawline is bent outward forming a chubby cheek (see fig. 22.5). The frontal view shows that the entire face is bent toward the right side along the bridge of the nose. All in all, the facial features are so distorted that it is impossible to identify the ruler.

Proposed Identifications

Nevertheless, numerous attempts have been made to identify the sitter. The size and the quality of the head indicate that it is a portrait of a ruler. And because it was discovered in Iran, it is most probably a king of the Seleucid dynasty, which ruled the Hellenistic East until the Parthian invasion of 141 BC. Several identifications have been proposed from Alexander the Great10 to Antiochus I and II or Seleucus II,11 to Antiochus III,12 Antiochus IV,13 and Antiochus VII.14 It has even been proposed that the head represents Kamnaskires I,15 the first king of a local Elymaean dynasty ruling under Parthian domination from the middle of the second century BC. But most of these identifications are merely speculations, based on historical considerations rather than on a comparison with the coin portraits of the respective kings. Because of the strong deformation of the face, some scholars admit that it is difficult or even impossible to identify the ruler.16 So despite Stein’s hope that expert examination of the head might lead to a solid identification, the depicted ruler even today is still unknown.17

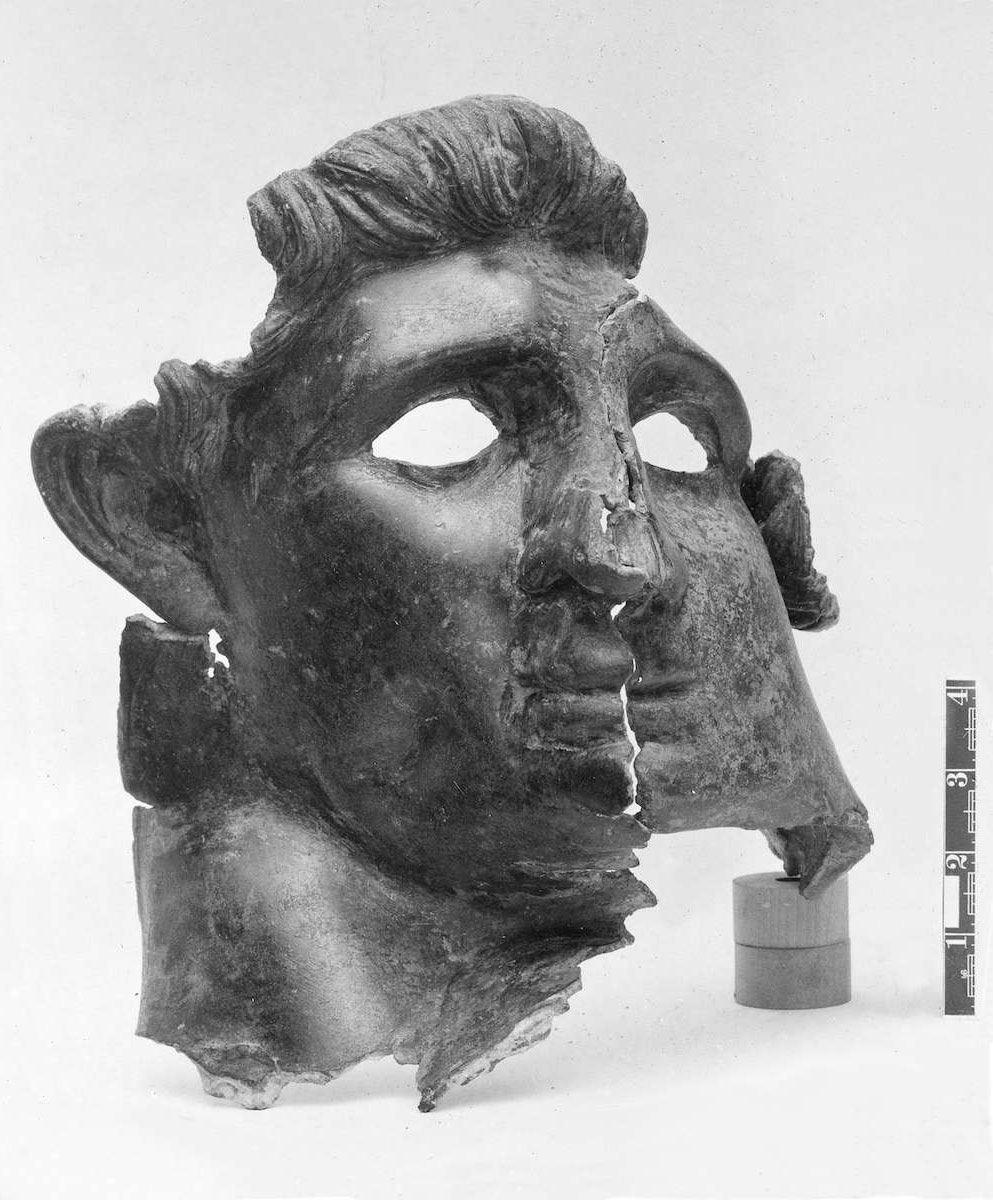

The Deliberate Breakage of the Head

As mentioned above, the head was broken into two pieces, and not merely for the purpose of melting down the metal. A photograph taken by Stein, preserved in the archives of the British Library and published here for the first time (fig. 22.3), shows the assembled parts of the head before restoration. The marks of a chisel are visible at the left side of the forehead (fig. 22.4). From there, the cut runs along the bridge of the nose to the chin. This is not the easiest line along which to divide a bronze head, therefore a nonpragmatic purpose of the partition has to be considered. Moreover, the dent in the right cheek was the result of several heavy blows with an edged tool, presumably a stone. The entire nose is pushed to the right side of the face, compressing the right side of the nose and bulging out the left cheek. The brutality of the actions and the deliberate distortion is obvious. Presumably the damage is a form of damnatio memoriae and the performers aimed to destroy the image and the memory of the ruler.

A First Reconstruction

A first attempt to reconstruct the original features of the portrait was made soon after its discovery. This is attested only by a photograph taken by Stein in 1937, which is reproduced in Michael Rostovtzeff’s The Social and Economic History of the Hellenistic World (Rostovtzeff 1941). The caption reads: “photograph of a lead cast supplied by Sir Aurel Stein” and “pro tempore in the British Museum.”18 This label seems surprising, because the piece of art was found in Iran and has long since been in the National Museum of Iran. But indeed the head made a short trip to London. Because Stein was a famous explorer, the Iranian authorities allowed him temporarily to send all finds from his expedition to the British Museum for examination.19 During its time in London, the sculptor Frank Bowcher made a piece mold of the head and produced a lead cast.20 The sculptor added the eye, squeezed out the depression in the right cheek, and put some parts of the head back in place, such as the neck.21 Unfortunately, this reconstruction could not be traced in the British Museum or in any other collection in the United Kingdom.

The Intended Reconstruction of the Original Features of the Head

The reconstruction of the original features of the Hellenistic ruler has been attempted again in a project started in August 2015. Based upon a series of digital images and by means of photogrammetry, a three-dimensional state model was created (fig. 22.5).22 This model, in turn, will serve to reconstruct the original physiognomy of the face by means of computer animation. For example, relatively well-preserved sections such as the upper cheek and eye of the right side of the face can be cut out, mirrored, and inserted on the other side of the head. Dents and bulges can be straightened, and the cracks joined. But it is still a work in progress. The reconstructed portrait should enable comparison to coin portraits of the Seleucid kings. Of course, such an approach has to consider the problems particular to comparison between a three-dimensional representation to two-dimensional coin designs. Nevertheless, we hope to be able to identify the sitter of the bronze portrait in the National Museum of Iran.

Other Remains of the Sculpture

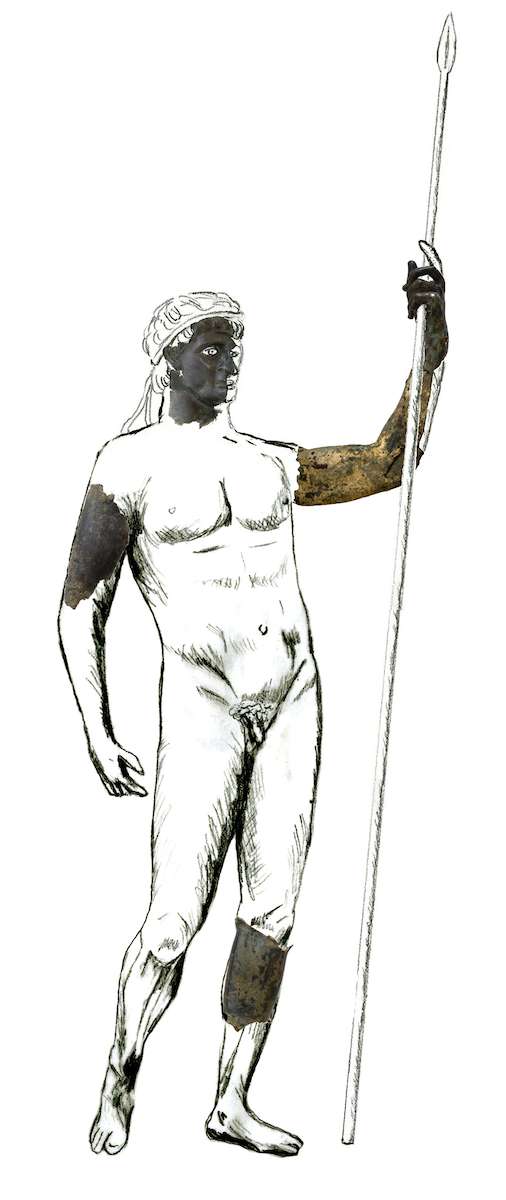

The photos from the Stein archive show further pieces of bronze sculpture, most likely belonging to the same sculpture as the bronze head in question. Some pieces were already illustrated in Stein’s report, but others have not been published until now. Unlike Stein’s plates, the photos from the archive provide an exact size scale. Five fragments show similar proportions, which are in turn in accordance with the scale of the head. Using the photos from the archives, colleagues at the National Museum of Iran easily identified the requested pieces, some of which were on display in the museum halls and others located in storage. Gathered together for the first time, it turned out that three fragments fit together.23 They form a raised left arm, the fingers in the pose of grasping a long object, perhaps a spear (fig. 22.6). Being significantly larger than the arm of an average-size European, the bronze arm indicates a sculpture slightly more than two meters (6 ½ ft.) tall. The inner surface of the sculptural fragment reveals details that are related to the casting process: two parallel raised lines with soft surfaces indicate a wax-to-wax join (fig. 22.7). Apparently two halves of a master mold met there, each lined with rectangular-cut wax sheets, and the seam between these sheets was covered with a wax strip. Fragments of a bare left leg from below the knee to above the ankle and of a right arm show the same technological features.24 Therefore, they most likely belong to the same sculpture.25

Reconstruction of the Statue Type

The preserved bronze fragments represent less than twenty percent of the statue. However, the bare limbs suggest that it was an undraped male. And with the position of the arm, one can infer a statue with a raised arm, leaning on a spear (fig. 22.8). The princely pose and the size of the sculpture indicate that it represented a ruler, even if a diadem is not preserved.

Trudy S. Kawami (1987) noted that “the presence of such an important work so far from a major city is difficult to explain.”26 However, judging from the first results of the Iranian-Italian excavations at Kal-e Chendar, the sculpture was erected at one of the most important religious places of ancient Elymais. From a Mediterranean point of view, the quality and “Greekness” of the reassembled statue may cause surprise, especially given its discovery in Iran. However, this just points out our limited knowledge of Hellenism in the regions east of the Tigris River.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung. My thanks go also to Dr. Jebrael Nokandeh, the director of the National Museum of Iran, who enabled the investigations, and to the entire museum staff, especially Firouzeh Sepidnameh (head of the Exhibition Department) and Masoumeh Ahmadi (International Affairs). Further thanks go to Ursula Sims-Williams, who drew my attention to the material of the Stein archives in the British Museum.

Notes

- The account of the discovery follows the report by Stein 1938 and 1940. ↩

- Godard 1937, 285-305, fig. 115-18; Stein 1940, 130-32, fig. 46-47; Ghirshman 1962, 89, fig. 99; Kawami 1987, 169, plate 11; Canepa 2015, 85–87, fig. 6.4. ↩

- First reports are Stein 1936 and 1938. The final report is included in Stein 1940, 130–35, 141–58. ↩

- Stein 1940, 145, plan II. ↩

- Stein 1940, 155. ↩

- The director of the Iranian Archaeological Services, André Godard, did a short investigation at the site in 1937, but the results are not published (Ghirshman 1976, 237). The structures recovered by Stein were already spoiled when the site was visited in 1968 by Klaus Schippmann (1971, 230) and in 1971 by Roman Ghirshman (Ghirshman 1976, 236). ↩

- Messina and Mehr Kian 2014. ↩

- Ghirshman 1962, 21 (“a seleucid king and his wife”); Colledge 1967, 156, 221 (“perhaps Antiochus IV and his queen”); idem 1987, 152 (“a female and a male portrait head”); Parlasca 1991, 465 (“two bronze heads”); Fischer 1970, 53, n. 111 (“Antiochus VII and his son Seleucus”). Fleischer (2016) considered the present state of the head to be a modern pastiche of two different ancient fragments. But after viewing the image discovered during the present investigation (fig. 22.3), he was convinced that they belong together (personal communication). ↩

- Stein (1940, 151, plate 5.1) believed a top part of a bronze head with a diadem to belong to the face. Because the fragment could not be traced in the National Museum of Iran, a direct comparison to the face was not possible. In any case, the dissimilarities in the style of the hair and possible overlaps above the left temple suggest that the pieces do not belong together. ↩

- Stein 1940, 151 (following a suggestion by the numismatist George F. Hill); Colledge 1977, 82; idem 1984, 22. ↩

- Mørkholm 1963, 67. ↩

- Herrmann 1977, 39. ↩

- Rostovtzeff 1941, 66, plate 10.1; Ghirshman 1954, 236, 278, plate 29b; idem 1962, 20–21; 1976, 237; Mussche 1955–56, 61; Berghe 1959, 64, plate 94c; Eddy 1961, 146; Richter 1965, 271; Porada 1962, 180, fig. 89; Lukonin 1967, plate 13; Colledge 1967, 156, 221; idem 1977, 82; idem 1984, 22; Herrmann 1977, 39; Parlasca 1991, 465. Sherwin-White (1984, 160) rules out an identification as Antiochus IV. ↩

- Fischer 1970, 53 n. 111; Houghton 1989; Smith 1988, 81, 119, 173; idem 1991, 226; Stewart 1990, 1: 218; 2: fig. 768. ↩

- Godard 1962, 183. Canepa (2015, 85) and, based on historical considerations, Boyce and Grenet (1991, 43) suggest a king of a local Elymaean dynasty. ↩

- Identifications considered too problematic by Kyrieleis 1980, 22 n. 28; Kawami 1987, 28; Boyce and Grenet 1991, 42–43 (“identifications of the mask are risky”); Fleischer 1991, 105–6; Fleischer 2000; Fleischer 2016; Mathiesen 1992, 88–89. ↩

- Stein 1938, 325. ↩

- Rostovtzeff 1941, plate 10.1. The cast was already illustrated by Stein (1938, fig. 9) and Picard (1939, fig. 35) with no reference that it is a reconstruction. ↩

- Stein 1940, XIV; Sarkosh Curtis and Pazooki 2004, 24; Sims-Williams 2004, 1. Stein incorporated several objects into his own findings, even though they were discovered by the locals. In 1938 these objects, including the bronze head, were returned to Tehran. ↩

- This procedure is documented only in correspondence between Stein and Fred Andrews, who supervised the examinations at the British Museum. The letters are published in extracts by Sims-Williams 2004. ↩

- If compared with the corresponding view of the head, the reconstruction is quite reliable, even if Boyce and Grenet (1991, 43) state that important details appear to have been completed from imagination. ↩

- The photogrammetry and the creation of the state model were made by Prof. Thomas Kersten and Dr. Maren Lindstaedt of the Photogrammetry & Laserscanning Lab of the HafenCity University in Hamburg. They will also conduct the technical implementation of the reconstruction. ↩

- National Museum of Iran, inv. 2471: a hand considered by Stein (1940, 151 plate 5.4) to belong to a colossal sculpture; inv. 2874: a large part of the arm not mentioned by Stein but illustrated by Godard (1937, fig. 126); inv. 2473: a fragment of the lower arm mentioned by neither Stein nor Godard. ↩

- National Museum of Iran, inv. 2478, the leg: Stein 1940, 151 plate 5.6; inv. 2470: a piece of the right arm mentioned by neither Stein nor Godard. ↩

- Other remains of bronze sculpture from Kal-e Chendar, which were examined within the project, do not show the straight elevated lines on the interior surface. ↩

- Kawami 1987, 28. ↩

Bibliography

- Berghe 1959

- Berghe, L. vanden. 1959. Archéologie de l’Iran ancien. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Boyce and Grenet 1991

- Boyce, M., and F. Grenet, 1991. A History of Zoroastrianism. Vol. 3: Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman Rule. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Canepa 2015

- Canepa, M. 2015. “Bronze Sculpture in the Hellenistic East.” In Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World, ed. J. M. Daehner and K. Lapatin, 83–93. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Colledge 1967

- Colledge, M. A. R. 1967. The Parthians. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Colledge 1977

- Colledge, M. A. R. 1977. Parthian Art. London: Paul Elek.

- Colledge 1984

- Colledge, M. A. R. 1984. “The Seleucid Kingdom.” In The Cambridge Ancient History: Plates to Volume VII, Part 1: The Hellenistic World to the Coming of the Romans, ed. R. Ling, 21–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Colledge 1987

- Colledge, M. A. R. 1987. “Greek and Non-Greek Interaction in the Art and Architecture of the Hellenistic East.” In Hellenism in the East: The Interaction of Greek and Non-Greek Civilizations from Syria to Central Asia after Alexander, ed. A. Kuhrt and S. Sherwin-White, 134–62. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Eddy 1961

- Eddy, S. F. 1961. The King Is Dead: Studies in the Near Eastern Resistance to Hellenism, 334–31 B.C. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Fischer 1970

- Fischer, T. 1970. “Untersuchungen zum Partherkrieg Antiochos’ VII.” PhD diss., Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

- Fleischer 1991

- Fleischer, R. 1991. Studien zur Seleukidischen Kunst, vol. 1. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Fleischer 2000

- Fleischer, R. 2000. “Portraitkopf eines Königs.” In 7000 Jahre persische Kunst: Meisterwerke aus dem Iranischen Nationalmuseum in Teheran, ed. W. Seipel, 227, no. 133. Milan: Skira, and Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum.

- Fleischer 2016

- Fleischer, R. 2016. “Der hellenistische Königskopf aus Šamī, Iran.“ In Man kann es sich nicht prächtig genug vorstellen! Festschrift für Dieter Salzmann zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. H.-H. Nieswandt and H. Schwarzer, vol. I, 269–86, pls. 30–31. Marsberg: Scriptorium.

- Ghirshman 1954

- Ghirshman, R. 1954. Iran, from the Earliest Times to the Islamic Conquest. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books.

- Ghirshman 1962

- Ghirshman, R. 1962. Iran: Parther und Sasaniden. Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Ghirshman 1976

- Ghirshman, R. 1976. Les terrasses sacrées de Bard-è Néchandeh et Masjid-i Sulaiman: L’Iran du sud-ouest du VIIIe s. av. n. ère au Ve s. de n. ère. Mémoires de la Délégation archéologique en Iran 45. Leiden and Paris: E. J. Brill.

- Godard 1937

- Godard, A. 1937. “Les statues parthes de Shami.” Athar-é Iran 2: 285–305.

- Godard 1962

- Godard, A. 1962. L’art de l’Iran. Paris: Arthaud.

- Herrmann 1977

- Herrmann, G. 1977. The Iranian Revival. Oxford: Elsevier-Phaidon.

- Houghton 1989

- Houghton, A. 1989. “A Victory Coin and the Parthian Wars of Antiochus VII.” In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Numismatics, London 1986, ed. I. A. Caradice, 65. London: International Association of Professional Numismatists.

- Kawami 1987

- Kawami, T. S. 1987. Monumental Art of the Parthian Period in Iran. Acta Iranica 26. Textes et Mémoirs (3rd ser.) 13. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Kyrieleis 1980

- Kyrieleis, H. 1980. Ein Bildnis des Königs Antiochos IV. von Syrien. Berliner Winckelmann-Programm 127. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- Lukonin 1967

- Lukonin, V. G. 1967. Persien, vol. 2. Munich: Nagel.

- Mathiesen 1992

- Mathiesen, H. E. 1992. Sculpture in the Parthian Empire: A Study in Chronology. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Messina and Mehr Kian 2014

- Messina, V., and J. Mehr Kian. 2014. “Return to Shami: Preliminary Survey of the Iranian-Italian Joint Expedition in Khuzestan at Kal-e Chendar.” Iran 52: 65–77.

- Mørkholm 1963

- Mørkholm, O. 1963. Studies in the Coinage of Antiochus IV of Syria. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

- Mussche 1955–56

- Mussche, H. F. 1955–56. “De Portretten de Seleuciden.“ Gentse Bijdragen tot de Kunstgeschiedenis 16: 55–69.

- Parlasca 1991

- Parlasca, K. 1991. “Zur hellenistischen Plastik im Vorderen Orient.“ In O ελληνισμóς στην Aνατoλή: Πρακτικά A’ Διεθνoύς Aρχαιoλoγικoύ Συνεδρίoυ, Δελφoί 6–9 Noεμβρίoυ 1986, 453–65. Athens: European Cultural Center Delphi.

- Picard 1939

- Picard, C. 1939. “Courrier de l’art antique.” Gazette des beaux arts (April): 201–34.

- Porada 1962

- Porada, E. 1962. Alt-Iran: Die Kunst in vorislamischer Zeit. Baden-Baden: Holle.

- Richter 1965

- Richter, G. M. A. 1965. The Portraits of the Greeks. London: Phaidon.

- Rostovtzeff 1941

- Rostovtzeff, M. 1941. The Social and Economic History of the Hellenistic World. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sarkosh Curtis and Pazooki 2004

- Sarkosh Curtis, V., and N. Pazooki. 2004. “Aurel Stein and Bahmna Karimi on Old Routes of Western Iran.” In Sir Aurel Stein: Proceedings of the British Museum Study Day, 23 March 2002, ed. H. Wang, 23–28. British Museum Occasional Paper 142. London: The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Schippmann 1971

- Schippmann, K. 1971. Die iranischen Feuerheiligtümer. Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten 31. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Sherwin-White 1984

- Sherwin-White, S. M. 1984. “Shami, the Seleucids and Dynastic Cult: A Note.” Iran 22: 160–61.

- Sims-Williams 2004

- Sims-Williams, U. 2004. “New Data Relating to Aurel Stein’s Expeditions to Iran: Correspondence with Fred Andrews, 1936–37.” In Sir Aurel Stein: Proceedings of the British Museum Study Day, 23 March 2002, ed. H. Wang, 23–28. British Museum Occasional Paper 142. London: The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Smith 1988

- Smith, R. R. R. 1988. Hellenistic Royal Portraits. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Smith 1991

- Smith, R. R. R. 1991. Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Stein 1936

- Stein, A. 1936. “Ancient Ways in Iran: A Fourth Journey I: Traces of Alexander the Great.” The Times (London) (July 6, 1936): 15–16.

- Stein 1938

- Stein, A. 1938. “An Archaeological Journey in Western Iran.” The Geographical Journal 42: 313–42.

- Stein 1940

- Stein, A. 1940. Old Routes of Western Īrān: Narrative of an Archaeological Journey Carried Out and Recorded by Sir Aurel Stein, K.C.I.E. London: MacMillan and Co.

- Stewart 1990

- Stewart, A. 1990. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. 2 vols. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.