42. A Technological Reexamination of the Piombino Apollo

- Benoît Mille, Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF) & UMR7055 Préhistoire et Technologie, Paris

- Sophie Descamps-Lequime, Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, Paris

Abstract

Important advances have recently been made in the study of the Piombino Apollo, thanks to the rediscovery in 2010 of a fragmentary inscribed lead tablet with the partial names of two sculptors, initially found in the statue during the 1842 restoration ordered by the Louvre museum. The new results fully support the assumption of an Archaizing creation and moreover confirm the Rhodian origin of the statue. They allow us to propose a very narrow dating for its manufacture (120–100 BC) and to suggest that the statue was erected in the Rhodian sanctuary of Athena Lindia.

Such an accurate context is rarely achieved for an ancient large bronze statue. Henceforward, the Piombino Apollo may be regarded as an essential milestone for the knowledge of bronze manufacturing techniques in the Late Hellenistic period. Because technological data on the Piombino Apollo were lacking, a complete reexamination was undertaken. X-radiography, bulk-metal analyses by ICP-AES, and nondestructive analysis of the copper and silver inlays—by particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) with the AGLAE particle accelerator—were conducted in 2014, seeking specific technological markers of a Rhodian workshop at the end of the second century BC.

Epigraphic and Stylistic Reevaluation of the Piombino Apollo

The Piombino Apollo (fig. 42.1) was among the statues gathered for the exhibition Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the accompanying symposium.1 It is an Archaizing work, as was already suggested by Jean Letronne in 1834, just two years after the bronze was discovered in the sea off the west coast of Piombino, Italy. Letronne’s interpretation was not accepted at the time, as the debate was then focused on the question of whether it was an Archaic or an Archaistic work. Later scholars moved on to another question: was it an Archaistic work from the fifth century BC or from the Hellenistic period? Even after Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway published a fundamental study of the statue in 1967, in which she convincingly argued in favor of a date at the end of the Hellenistic period, there were still those who doubted her conclusions. This was particularly so because a subsidiary question remained without an answer. This question was linked with the loss, more than a century before, of a fragmentary inscribed lead strip, said to have been found within the statue, on which the names of two Hellenistic sculptors were said to have been engraved. Because that lost inscription had been declared a fake—and this assertion could no longer be verified—Ridgway’s dating was not accepted as proved. A further step supporting a Late Hellenistic date was the discovery in 1977 of another bronze Apollo2 at Pompeii, in the House of Gaius Julius Polybius, that appeared to be so close in attitude and style that the two statues were declared virtual twins, possibly elaborated from the same master molds.3

One of the opportunities afforded by the exhibition Power and Pathos was to accommodate close comparisons between similar statues put on display together. For the first time, the two Apollos were shown in the same room, and it appeared that, even if they obviously hark back to the same prototype and both are associated with the same Late Hellenistic and Early Imperial retrospective trend, their differences are as important as their similarities. The Piombino Apollo is squatter and less slender, while the Pompeian Apollo is taller. Unearthed with bronze tendrils, the latter was originally conceived as a trapezophoros lychnouchos, a decorative tray-bearer for adorning and lighting a triclinium.4 The tendrils, when fixed in the statue’s hands, were intended to support a ferculum (a table top) on which to place lamps or other items for the banquet. No traces in the hands of the Piombino Apollo indicate that he too would have been a lychnouchos by original intent.

The fragments of the inscribed lead strip, which were rediscovered in the Louvre’s storerooms in 2010, were shown close to the statues in Power and Pathos. During the restoration of the bronze in 1842, the lead strip had been extracted in four fragments with great difficulty through the empty eye sockets, at the same time that very hard material remaining in the chest was removed. Three of these fragments had been preserved. As noted above, they retain two partial Greek names, which were deciphered in the year of their discovery but immediately declared a forgery.

However, once rediscovered, the strip as well as the sculptors’ names were proved authentic by the historian and epigraphist Nathan Badoud, who recently republished the inscription.5 He confirmed the name of the first artist, Menodotos of Tyre, and proposed Xenophon of Rhodes for the second one. The fragment that did not survive was the longest, and the second in sequence. The inscription is currently read as “Menodotos of Tyre and Xenophon of Rhodes made it.” Menodotos belonged to a well-known Rhodian family workshop. He was the son of Artemidoros, the founder of the workshop, who had emigrated from Tyre and had settled on Rhodes in the 150s BC. According to Badoud, Menodotos was active from about 129 to 100 BC. Other known signatures, which survive on stone bases, attest that he worked with his father and with his younger brother Charmolas.6 The lead strip from inside the Piombino Apollo reveals a third collaboration, which could have been with Xenophon, son of Pausanias. (The signature with Charmolas comes from Athens.) When he worked with his father, Menodotos elaborated a bronze portrait of Pasiphon, son of Epilykos, who was priest of Athana Lindia and therefore eponymous for the year 124 BC. This portrait was erected in the Rhodian sanctuary of Athana (or Athena) Lindia. And indeed, according to Badoud, regarding the Piombino Apollo, another clue might lead to the same Rhodian sanctuary. The votive three-line silver inlaid inscription, cut after casting into the statue’s left foot, gives not only the two last letters of the dedicator’s name but also two lines indicating that the statue was offered to Athena as a tithe. Thus, it is a statue of Apollo dedicated to Athena. The alphabet, the letters’ shapes, and the meaning of the dedication point to the Rhodian sanctuary of Athana Lindia where a tradition of visiting gods is firmly attested.7

Actually, the Piombino Apollo fits in well with an Eastern Archaizing sculptural tradition of the Late Hellenistic period, as illustrated by a marble head from Rhodes, larger than life-size and echoing a bronze in having inserted eyes, now lost (fig. 42.2).8 The similarities lie in the particular rendering of the sophisticated parted hair, with the presence of a thin fillet; in the two overlapping rows of corkscrew curls around the forehead; in the sinuous and broad incised lines that start from the top of the head; and even in the rendering of the ears.

Thus, the fact that the statue was most probably made in Rhodes during the last quarter of the second century BC is supported by external evidence. This accurate context justified a scientific reexamination of the statue, which is the subject of this paper.

Laboratory Reexamination of the Piombino Apollo

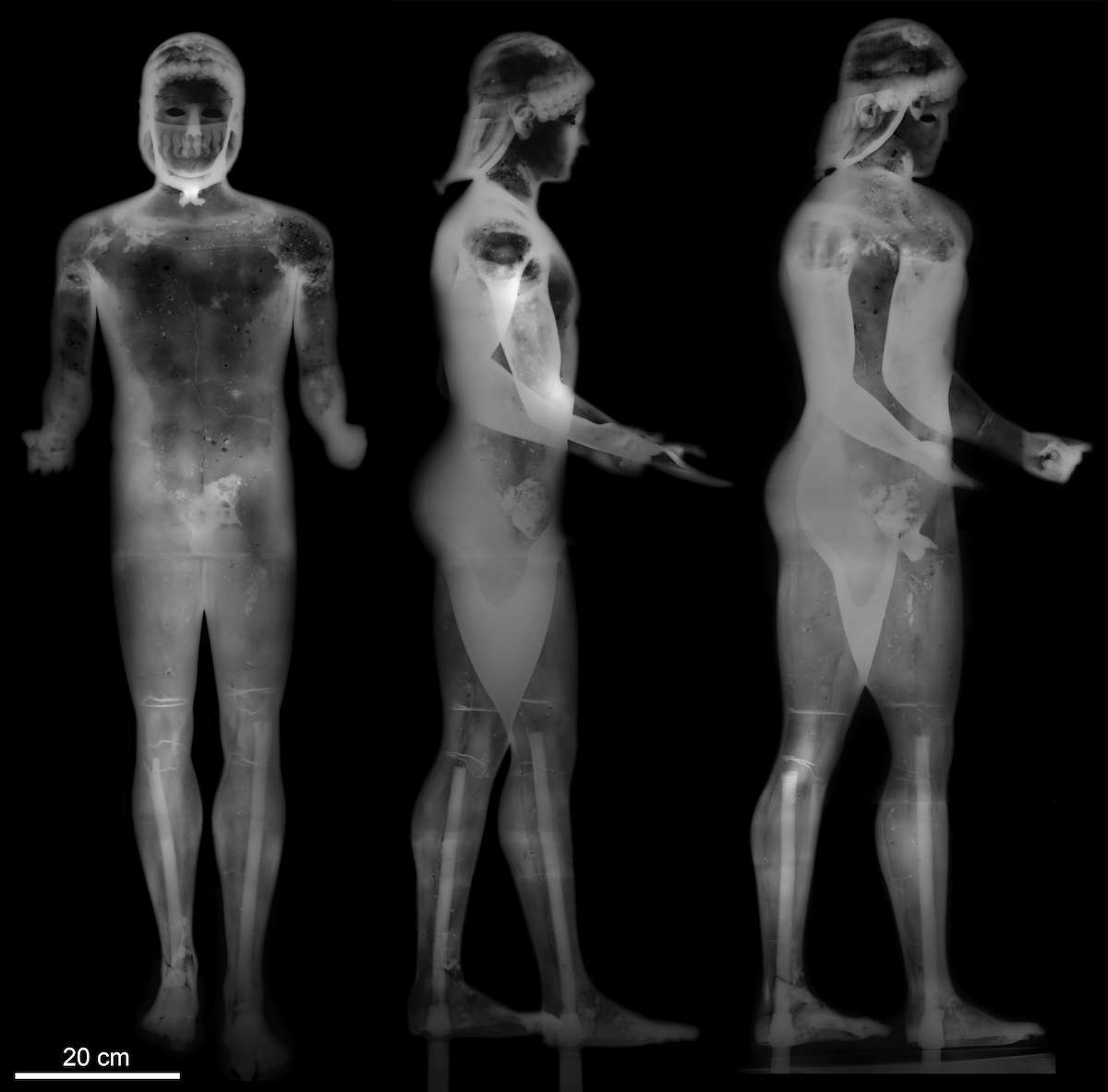

Analytical Procedure: An endoscopic examination was first performed during a kind of multidisciplinary brainstorming session within the bronze gallery of the Louvre Museum and then at the sickbed of the statue, as it were, in the laboratory, around which a number of eminent scholars gathered.9 This day marked the beginning of the technological reexamination of the statue. In addition to endoscopy and a very careful examination by eye, extensive X-radiography was carried out at the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF) (fig. 42.3). Fourteen bronze samples were also taken by microdrilling in order to document and to compare the elemental composition of the different parts of the statue; these samples were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES).10 Non-destructive analyses of the silver and copper inlays were performed by particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE), thanks to the AGLAE particle accelerator.

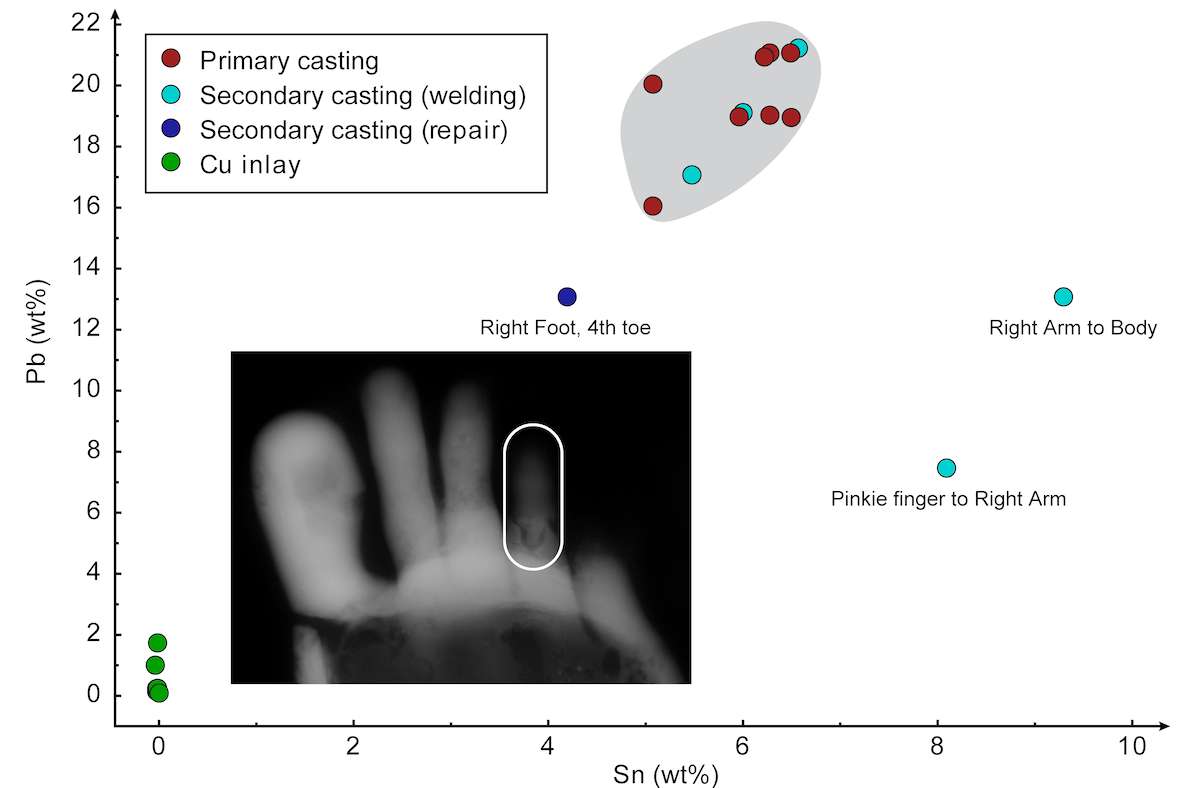

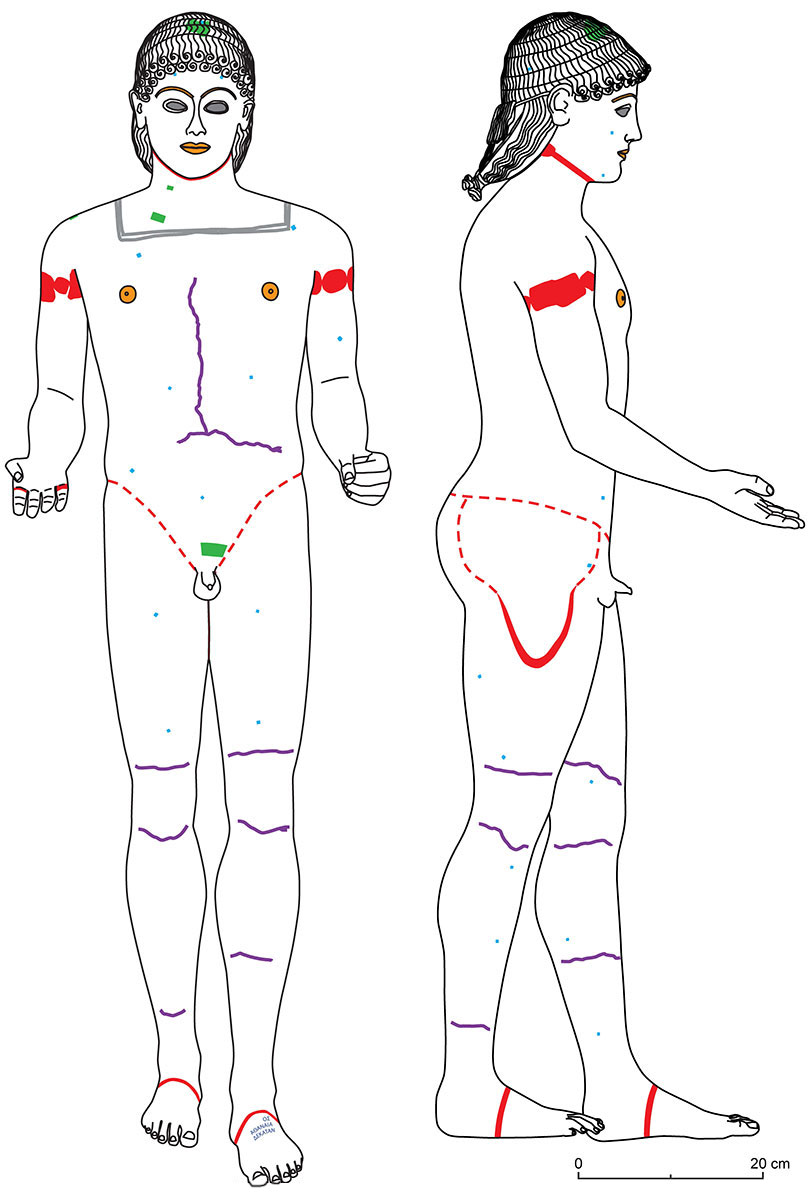

Metal Composition: A high-lead bronze was chosen for the primary castings, and the composition is virtually the same for all parts of the statue (head, body, arms, legs, fingers): 6% tin and 19.5% lead. The lips, eyebrows, and nipples are made of unalloyed copper: no tin, up to 2% lead. The letters of the inscription on the foot are inlaid with silver slightly alloyed with copper (3%), and containing 0.5% gold as its main impurity (fig. 42.4a; see also table 42.1 and table 42.2 for the complete results).

| Analysis No. | Sample location | Casting type | Cu | Sn | Pb | Ag | As | Fe | Ni | S | Sb | Zn | Au | Ba | Bi | Cd | Co | Cr | Ge | Hg | In | Mg | Mn | Mo | P | Se | Te | Ti | U | V | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( in wt. %) | ( in wt. ppm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FZ20669-a | Head (curl) | PC | X | 6.3 ±0.6 | 21 ±2 | 0.046 ±0.005 | 0.16 ±0.02 | 0.045 ±0.005 | 0.075 ±0.008 | 0.15 ±0.01 | 0.059 ±0.006 | nd <0.00069 | 55 ±5 | nd <0.2 | 140 ±14 | nd <0.2 | 228 ±23 | nd <0.9 | nd <3.3 | 4.1 ±0.4 | 10 ±4 | nd <3.1 | nd <0.0 | 2.6° <8.4 | nd <24 >2.5 | 12 ±2 | 27 ±5 | nd <0.3 | nd <9.3 | nd <0.2 | nd <2.2 |

| FZ20669-b | Welding: head - body (left basin) | SC (welding) | X | 6.5 ±0.7 | 21 ±2 | 0.047 ±0.005 | 0.17 ±0.02 | 0.041 ±0.004 | 0.076 ±0.008 | 0.15 ±0.01 | 0.061 ±0.006 | nd <0.00080 | 42 ±4 | nd <0.3 | 138 ±14 | nd <0.3 | 227 ±23 | nd <1.0 | nd <3.9 | 4.1 ±0.4 | 8.2 ±1.7 | nd <3.6 | nd <0.1 | nd <2.9 | nd <28 | 9.9 ±1.1 | 31 ±3 | nd <0.3 | nd <11 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.6 |

| FZ20669-c | Body (right flank) | PC | X | 5.1 ±0.5 | 20 ±2 | 0.043 ±0.004 | 0.17 ±0.02 | 0.12 ±0.01 | 0.068 ±0.007 | 0.13 ±0.01 | 0.055 ±0.006 | nd <0.00079 | 37 ±4 | nd <0.3 | 63 ±6 | nd <0.3 | 204 ±20 | nd <1.0 | nd <3.8 | 4.2 ±0.5 | 5.5° <8.0 >2.4 | nd <3.6 | nd <0.1 | nd <2.9 | nd <28 | 12 ±1 | 32 ±9 | nd <0.3 | nd <11 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.5 |

| FZ20669-d | Welding: right arm - body | SC (welding) | X | 9.3 ±0.9 | 13 ±1 | 0.081 ±0.008 | 0.51 ±0.05 | 0.11 ±0.01 | 0.071 ±0.007 | 0.26 ±0.03 | 0.11 ±0.01 | 0.047 ±0.005 | 27 ±3 | nd <0.3 | 122 ±12 | nd <0.3 | 40 ±4 | nd <1.1 | nd <4.3 | 4.2 ±1.3 | 9.6 ±4.8 | nd <4.0 | nd <0.1 | nd <3.3 | nd <31 | 24 ±2 | 26 ±9 | nd <0.4 | nd <12 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.9 |

| FZ20669-e | Right arm | PC | X | 6.5 ±0.6 | 21 ±2 | 0.045 ±0.005 | 0.16 ±0.02 | 0.043 ±0.004 | 0.073 ±0.007 | 0.19 ±0.02 | 0.059 ±0.006 | nd <0.00096 | 27 ±3 | nd <0.3 | 138 ±14 | nd <0.3 | 228 ±23 | nd <1.2 | nd <4.6 | 4 ±0.4 | 9.4° <9.7 >2.9 | nd <4.3 | nd <0.1 | nd <3.5 | nd <34 | 9.1° <11.5 >3.4 | 28 ±3 | nd <0.4 | nd <13 | nd <0.3 | nd <3.1 |

| FZ20669-f | Pinkie finger | PC | X | 6 ±0.6 | 19 ±2 | 0.042 ±0.004 | 0.15 ±0.02 | 0.035 ±0.003 | 0.069 ±0.007 | 0.13 ±0.01 | 0.054 ±0.005 | nd <0.00096 | 24 ±2 | nd <0.3 | 128 ±13 | nd <0.3 | 208 ±21 | nd <1.2 | nd <4.6 | 3.7 ±0.7 | 3.7° <9.7 >2.9 | nd <4.3 | nd <0.1 | nd <3.5 | nd <34 | 6.5° <11.5 >3.4 | 21 ±4 | nd <0.4 | nd <13 | nd <0.3 | nd <3.1 |

| FZ20669-g | Welding: pinkie finger - right arm | SC (welding) | X | 8.1 ±0.8 | 7.4 ±0.7 | 0.051 ±0.005 | 0.35 ±0.03 | 0.00081 ±0.00008 | 0.031 ±0.003 | 0.051° >0.020 <0.067 | 0.078 ±0.008 | nd <0.00070 | 18 ±2 | nd <0.2 | 57 ±6 | nd <0.2 | 25 ±3 | nd <0.9 | nd <3.4 | 3.9 ±0.4 | 2.2° <7.0 >2.1 | nd <3.1 | nd <0.0 | nd <2.5 | nd <24 | 36 ±4 | 16 ±6 | nd <0.3 | nd <9.3 | nd <0.2 | nd <2.2 |

| FZ20669-h | Left leg | PC | X | 5.1 ±0.5 | 16 ±2 | 0.04 ±0.004 | 0.18 ±0.02 | 0.13 ±0.01 | 0.068 ±0.007 | 0.13 ±0.01 | 0.053 ±0.005 | nd <0.00066 | 29 ±3 | nd <0.2 | 57 ±6 | nd <0.2 | 220 ±22 | nd <0.8 | nd <3.2 | 4.5 ±0.6 | 9.7 ±1.1 | nd <3.0 | nd <0.0 | nd <2.4 | nd <23 | 12 ±2 | 28 ±3 | nd <0.3 | nd <8.9 | nd <0.2 | nd <2.1 |

| FZ20669-i | Welding: left foot - left leg | SC (welding) | X | 6 ±0.6 | 19 ±2 | 0.044 ±0.004 | 0.17 ±0.02 | 0.025 ±0.003 | 0.075 ±0.007 | 0.13 ±0.01 | 0.056 ±0.006 | nd <0.00073 | 63 ±6 | nd <0.3 | 66 ±7 | nd <0.2 | 112 ±11 | nd <0.9 | nd <3.6 | 4 ±0.6 | 4.3° <7.4 >2.2 | nd <3.3 | nd <0.0 | nd <2.7 | nd <26 | 12 ±2 | 35 ±7 | nd <0.3 | nd <9.9 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.3 |

| FZ20669-j | Left foot (forefoot) | PC | X | 6.3 ±0.6 | 21 ±2 | 0.047 ±0.005 | 0.16 ±0.02 | 0.056 ±0.006 | 0.075 ±0.007 | 0.15 ±0.02 | 0.06 ±0.006 | nd <0.00068 | 39 ±4 | nd <0.2 | 141 ±14 | nd <0.2 | 224 ±22 | nd <0.9 | nd <3.3 | 4 ±0.7 | 6.9 ±1.7 | nd <3.1 | nd <0.0 | nd <2.5 | nd <24 | 10 ±2 | 33 ±6 | nd <0.3 | nd <9.2 | nd <0.2 | nd <2.2 |

| FZ20669-k | Right leg | PC | X | 6.3 ±0.6 | 19 ±2 | 0.045 ±0.005 | 0.18 ±0.02 | 0.024 ±0.002 | 0.072 ±0.007 | 0.12 ±0.01 | 0.057 ±0.006 | nd <0.00089 | 40 ±4 | nd <0.3 | 60 ±6 | nd <0.3 | 110 ±11 | nd <1.1 | nd <4.3 | 4.4 ±0.4 | 4.8° <9.0 >2.7 | nd <4.0 | nd <0.1 | nd <3.3 | nd <31 | 13 ±2 | 30 ±4 | nd <0.4 | nd <12 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.9 |

| FZ20669-l | Welding: right foot - right leg | SC (welding) | X | 5.5 ±0.5 | 17 ±2 | 0.041 ±0.004 | 0.16 ±0.02 | 0.025 ±0.003 | 0.075 ±0.008 | 0.13 ±0.01 | 0.051 ±0.005 | nd <0.00072 | 35 ±4 | nd <0.2 | 54 ±7 | nd <0.2 | 114 ±11 | nd <0.9 | nd <3.5 | 4.4 ±0.7 | 6.2° <7.3 >2.2 | nd <3.2 | nd <0.0 | nd <2.6 | nd <25 | 9.8 ±1.0 | 29 ±9 | nd <0.3 | nd <9.7 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.3 |

| FZ20669-m | Right foot (forefoot) | PC | X | 6.5 ±0.7 | 19 ±2 | 0.046 ±0.005 | 0.17 ±0.02 | 0.06 ±0.006 | 0.077 ±0.008 | 0.16 ±0.02 | 0.061 ±0.006 | nd <0.00078 | 31 ±3 | nd <0.3 | 135 ±14 | nd <0.3 | 229 ±23 | nd <1.0 | nd <3.8 | 4 ±0.4 | 9 ±3.5 | nd <3.5 | nd <0.0 | nd <2.8 | nd <27 | 9.8 ±3.7 | 33 ±13 | nd <0.3 | nd <10 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.5 |

| FZ20669-n | Fourth toe of the right foot | SC (repair) | X | 4.2 ±0.4 | 13 ±1 | 0.18 ±0.02 | 0.4 ±0.04 | 0.0082 ±0.0008 | 0.087 ±0.009 | 0.15 ±0.02 | 0.28 ±0.03 | 0.69 ±0.07 | 52 ±5 | nd <0.3 | 393 ±39 | nd <0.3 | 103 ±10 | nd <1.0 | nd <3.9 | 5.3 ±0.5 | 9.3 ±3.3 | nd <3.6 | nd <0.1 | nd <3.0 | nd <28 | 21 ±3 | 31 ±6 | nd <0.3 | nd <11 | nd <0.3 | nd <2.6 |

| ° = below the limit of quantification. PC = primary casting. SC = secondary casting. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Analysis No. | Location | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Mo | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | Au | Hg | Pb | Bi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07mai006 | Cu - right eyebrow | <0.3 | <0.05 | 0.33 | <0.0058 | 0.067 | 98.3 | <0.017 | 0.032 | <0.0071 | <0.0098 | 0.071 | <0.015 | <0.009 | <0.022 | <0.021 | <0.02 | <0.0085 | <0.0094 | 0.96 | <0.0099 |

| 07mai007 | Cu - left eyebrow | <0.26 | <0.066 | 0.28 | <0.0026 | 0.077 | 99.1 | <0.018 | <0.021 | <0.0023 | <0.0053 | 0.076 | <0.0087 | <0.0073 | <0.013 | 0.07 | <0.0091 | <0.011 | <0.0041 | 0.098 | <0.0063 |

| 07mai008 | Cu - upper lip | <0.32 | <0.048 | 0.42 | <0.012 | 0.066 | 97.6 | <0.025 | 0.19 | <0.0084 | <0.0052 | 0.055 | <0.019 | <0.0053 | <0.045 | <0.016 | <0.029 | <0.013 | <0.0094 | 1.7 | <0.014 |

| 07mai010 | Cu - lower lip | <0.21 | <0.077 | 0.47 | <0.017 | 0.072 | 98.8 | <0.024 | 0.2 | <0.005 | <0.011 | 0.029 | <0.0098 | <0.0032 | <0.031 | <0.031 | <0.024 | <0.014 | <0.0079 | 0.18 | <0.0086 |

| 07mai011 | Cu - right nipple | <0.29 | <0.057 | 0.28 | <0.014 | 0.093 | 98.9 | <0.018 | 0.14 | <0.0042 | <0.011 | 0.056 | <0.026 | <0.008 | <0.016 | <0.051 | <0.021 | <0.012 | <0.0082 | 0.17 | <0.0064 |

| 07mai012 | Cu - left nipple | <0.28 | <0.065 | 0.46 | 0.097 | 0.095 | 98.7 | <0.018 | 0.2 | <0.0049 | <0.0048 | 0.048 | <0.018 | <0.0069 | <0.0059 | <0.029 | <0.025 | <0.01 | <0.004 | 0.07 | <0.0066 |

| 07mai013 | Ag - left foot | <0.36 | <0.039 | 0.33 | <0.013 | 0.067 | 9.8 | <0.011 | 0.085 | <0.0036 | <0.0024 | 85.8 | <0.036 | <0.084 | 2.9 | <0.047 | <0.031 | 0.45 | <0.0051 | 2.1 | <0.0072 |

| 07mai014 | Ag - left foot - no scan | <0.35 | <0.059 | 0.024 | <0.0086 | 0.054 | 3.1 | <0.0059 | <0.014 | <0.0036 | <0.0021 | 95.9 | <0.027 | <0.074 | <0.59 | <0.04 | <0.023 | 0.48 | <0.0026 | 0.41 | 0.029 |

The alloy used as filler metal for welding (the so-called secondary casting) matches perfectly the one used for primary castings (head to body, left and right feet to the corresponding legs), with two exceptions: the join of the right arm to the body (sample FZ20669-d), and the join of the pinkie finger to the right hand (sample FZ20669-g), which contain more tin and less lead (see fig. 42.4a).

Last but not least, the fourth toe of the right foot (sample FZ20669-n) was repaired in antiquity, as can be seen very clearly on a detail of the X-radiograph: a tenon was inserted in the foot at the base of the broken toe, and the missing part was directly cast on the tenon. Here, the alloy is also different, only 4% tin and 12% lead (see fig. 42.4a). Given the difference in the alloy, it seems more likely that the toe repair was not made in the original workshop but was part of a later restoration, during the ancient “lifetime” of the statue.

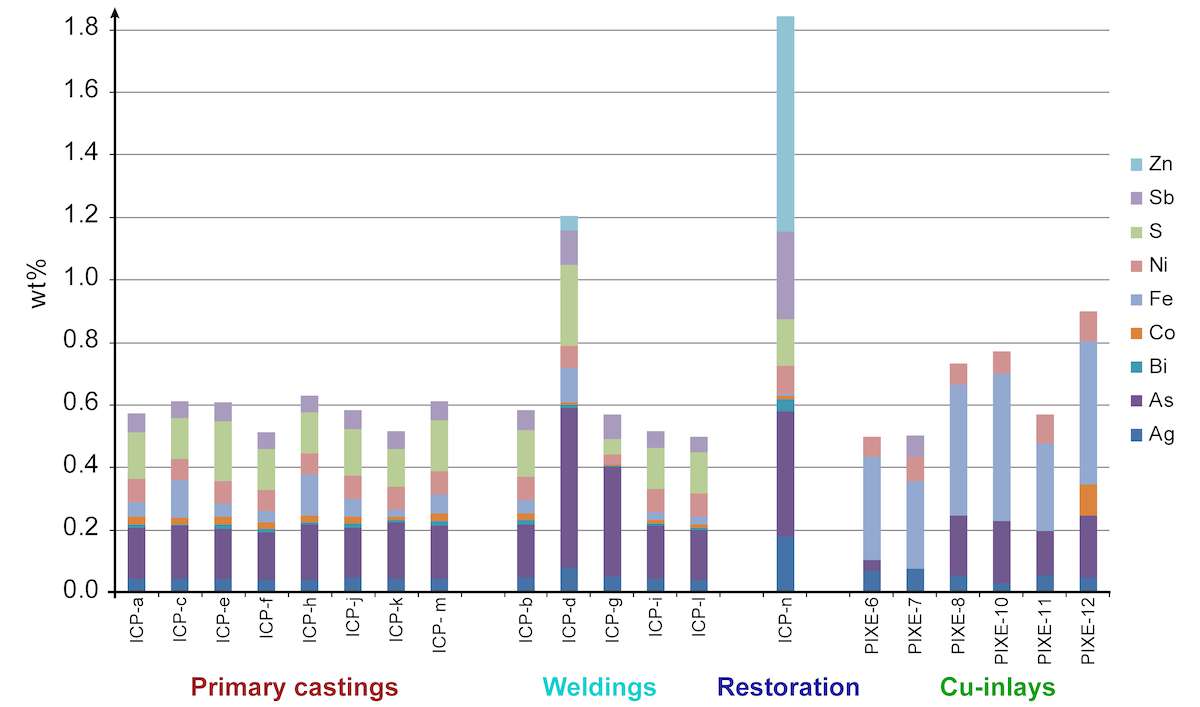

When we look at the main impurities in the metal, the first thing to notice is that the primary and secondary castings share identical impurities spectra: a global level of 0.6%, with arsenic and sulfur as the main impurities (fig. 42.4b).

The pattern observed for the fourth toe is very different, with high levels of arsenic, bismuth, antimony, and zinc, confirming the hypothesis of a later repair. Interesting is the fact that the weld join of the right arm, which shows a peculiar alloy, is also distinctive for its impurities, and quite close to the pattern of the fourth toe. This may suggest that the restoration was not limited to the replacement of the fourth toe, but that the statue underwent a major intervention.

As to the copper inlays, at least two impurities patterns stand out from that of the primary castings: iron-rich without arsenic for the eyebrows; and arsenic- and iron-rich for the lips and the nipples (see table 42.2).

Casting Technique: Working the Wax

The wax was primarily worked by the indirect process, resulting in thin and even metal walls. We were able to take a limited number of direct measurements using a thickness gauge, through the eyes of the statue and at the aperture of the feet. The walls were between 3 and 4 mm thick, and X-radiography confirmed that the metal walls were of a consistent thickness throughout (see fig. 42.3).11 Based on X-radiography combined with surface and endoscopic examinations, we concluded that wax was used to fill the inside of smaller details in relief, such as the nose, the ears, the toes, and the fingers. Given also the fact that no wax-to-wax joins were detected, except for a bib-like shape below the neck, the artisans probably used the slush technique: some liquid wax was poured into the corresponding molds of each section to deposit a layer of uniform thickness, the excess liquid wax being subsequently removed by inverting the mold.

A noticeable exception to the indirect process is the complex hairstyle, which shows some extra work done in the positive of the wax (fig. 42.5). In the skull area, each strand of hair has been very finely figured and engraved in the wax. Hair undulations combine with slight indentations of the head to produce the effect of a stepped hairstyle in four successive waves. At the forehead, from ear to ear, the strands end in a double row of corkscrew curls, which were directly carved and then added to the head one by one (fig. 42.6).

The bib-like shape below the neck previously mentioned corresponds to the only detectable wax-to-wax join. The Piombino Apollo is not the only case to present this peculiar feature: other examples of statues from the Late Hellenistic and Early Imperial periods are also known.12 It is possible that this join could indicate a certain division of labor in the workshop, where the most intricate parts such as face and hair, requiring extensive, delicate work on the wax, were made by a very skilled craftsman and then added to the other parts of the statue.

Casting Technique: Joining the Parts

X-radiographs helped to determine the join locations (see fig. 42.3), allowing us to infer a casting map, which lists the separately cast parts and shows where the wax model was cut.13

We know that the statue was cast in nine or ten sections: head, body, arms, legs, two fingers, and the anterior parts of the feet. At least one of the legs would likely have been cast separately. But the join is so perfect that we were unable to detect it. Thus, one leg may or may not have been cast together with the body (fig. 42.7).

A flow fusion welding process was used to join the different sections of the statue, involving a filler metal of the same composition as the one used for the primary castings (see also ”Casting Technique: Working the Wax”).14 The high-level mastery in joining is a very meaningful aspect to record: not only were the bronze casters able to use a broad array of preparation techniques, but they also achieved welds without any defects. Three different preparations for the joins were observed. First, welding in basins for the arms (see fig. 42.5): such joins are known from at least the fifth century BC to the third century AD.15 Second, platform welding for the head and between the legs (see fig. 42.5 and fig. 42.8): this kind of preparation is not known before the Hellenistic period.16 Third, linear joins are observed on the feet (see fig. 42.5). Such joins are totally atypical for the Late Hellenistic period but are very well known on statues from the Severe style period (ca. 480–450 BC), as for example on the Poseidon statue from Cape Artemision.17 This technical trait, purposefully adopted from statues of the first half of the fifth century BC, reinforces the notion that the Apollo was executed in Archaic-revival style, as it would have been easily visible by anyone on close examination.

Casting Technique: Core Pins and Repairs to the Casting Defects

Important observations were made concerning the core pins, or chaplets (square rods measuring 3.5 x 3.5 mm in section), since they were made not of iron but of a copper alloy. Even with the help of X-radiography, they are particularly difficult to detect, and we probably missed a few of them. From those that have been detected, it seems that they were very regularly arranged, every 20 centimeters or so (see fig. 42.5). Due to their metal composition, the core pins were often partially melted during the cast. It was therefore unnecessary to remove them or to hide the corresponding holes, saving the workshop a lot of labor-intensive repairs. Such a practice is just the kind of technological marker we are looking for, as the core pins evidenced here seem very specific to the workshop that manufactured the statue.

Exceptional is the fact that the Apollo statue was cast virtually free of defects, compared to other statues from the Hellenistic period. The smallest defects were hidden by quadrangular bronze patches, whereas a larger lacuna on top of the head was filled by a secondary casting (see fig. 42.5).

Conclusion

Certain questions concerning the Piombino Apollo remain open. Why did the sculptors hide their signatures inside the bronze? Let us remember that it was common for craftsmen to have their names inscribed on the bases that supported their works. This tradition was particularly well attested in Rhodes where there are numerous stone bases for bronze statues, from the fourth century onward, some of them signed not only by the sculptor but by the bronze-caster as well.18 They could have engraved their names on the actual statues or on their plinths if there were any.

The hidden signatures were never supposed to be read again. But this was not the case for the votive inscription on the left foot, which could be read by anyone looking at the statue. This inscription could be interpreted as witnessing the fact that the statue once stood in a Rhodian sanctuary. If so, did the pilgrims visiting Rhodes see the Apollo statue as a true Archaic ex-voto and were thus deceived by the style? Or, on the contrary, did they understand it as an Archaizing creation?

Another question concerns the shipment to Italy. The statue was found in a shipwreck, but we have no evidence that it was taken as booty or was displaced by looting. Still, the bronze does bear traces of repair. If the new study confirms that the left foot was never broken and restored in antiquity, as has been suggested more than once,19 it is still clear that the fourth toe was recast and that this took place most probably when the right arm was reattached to the shoulder, since the weld join seems to come from the same metal batch. This means not only that a certain time had passed between the creation of the statue and this secondary intervention, but also that there was enough peaceful time for a restoration to be planned and completed. This doesn’t fit well with the violent desecration of a sanctuary followed by a shipment as booty.

Another solution can’t be ruled out: the possibility that Menodotos and Xenophon intentionally fabricated a forgery. The red copper inlays on the eyebrows were intended to suggest a Late Archaic or Early Classical sculpture, and so do the linear joins on the feet. In this scenario, the Apollo would have been executed directly for commercial purposes and purchased to adorn a Roman place. The votive inscription, which bestowed a Rhodian sacred origin to the statue, could have been added in order to deceive the viewer and the potential buyer regarding the true importance of the bronze.20 No one can tell, however, whether the Apollo was intended to be displayed in a Roman house as a genuine work of art or, if slightly modified with attributes, as a lychnouchos. Be that as it may, it offers the first and, up to now, only testimony of the practice of hiding signatures in a bronze statue.

It is rare to be able to pinpoint the context of production for an ancient large bronze statue. Thus, from now on, the Piombino Apollo is to be regarded as an essential reference point not only for the study of Rhodian bronze manufacture but more generally for the knowledge of large bronzes’ manufacturing techniques during the Late Hellenistic period.

Very few bronze statues have been uncovered on Rhodes.21 Technological data of such finds should be compared with data revealed by the examination of the Piombino Apollo in order to verify the extremely high level and mastery of Rhodian workshops.22 As a work dated to the very end of the second century BC, the Piombino Apollo was cast with a distinctive low-tin and high-lead copper alloy with a readily identifiable pattern of impurities. The slush process was used to achieve the thin, even wax walls of the main parts of the statue, thus eliminating two possible sources of casting defects of the indirect lost-wax technique: (1) the wall thickness cannot be less than the minimum chosen by the foundryman (here 3 mm); and (2) there are no wax-to-wax joins. Distinctive core pins made of a copper alloy rather than iron are in evidence: removing them was unnecessary, thus eliminating one common cause of defects needing repair. Last but not least, the joins are extremely well executed. As a consequence, the statue appears to be virtually free of casting defects. Could these results, which reveal a high skill in casting, characterize the Rhodian industry as evoked by Carol C. Mattusch already in 1998?23 In other words, given the well-attested intensive production of Rhodian workshops, was there something like a Rhodian bronze technique? In point of fact, statues said to have been found in Rhodes, such as the Eros Sleeping at the Metropolitan Museum,24 also present very few casting defects. This is also the case for the fragments excavated within the remains of ancient Rhodian foundries, which, moreover, are all characterized by a low-tin and high-lead copper alloy.25

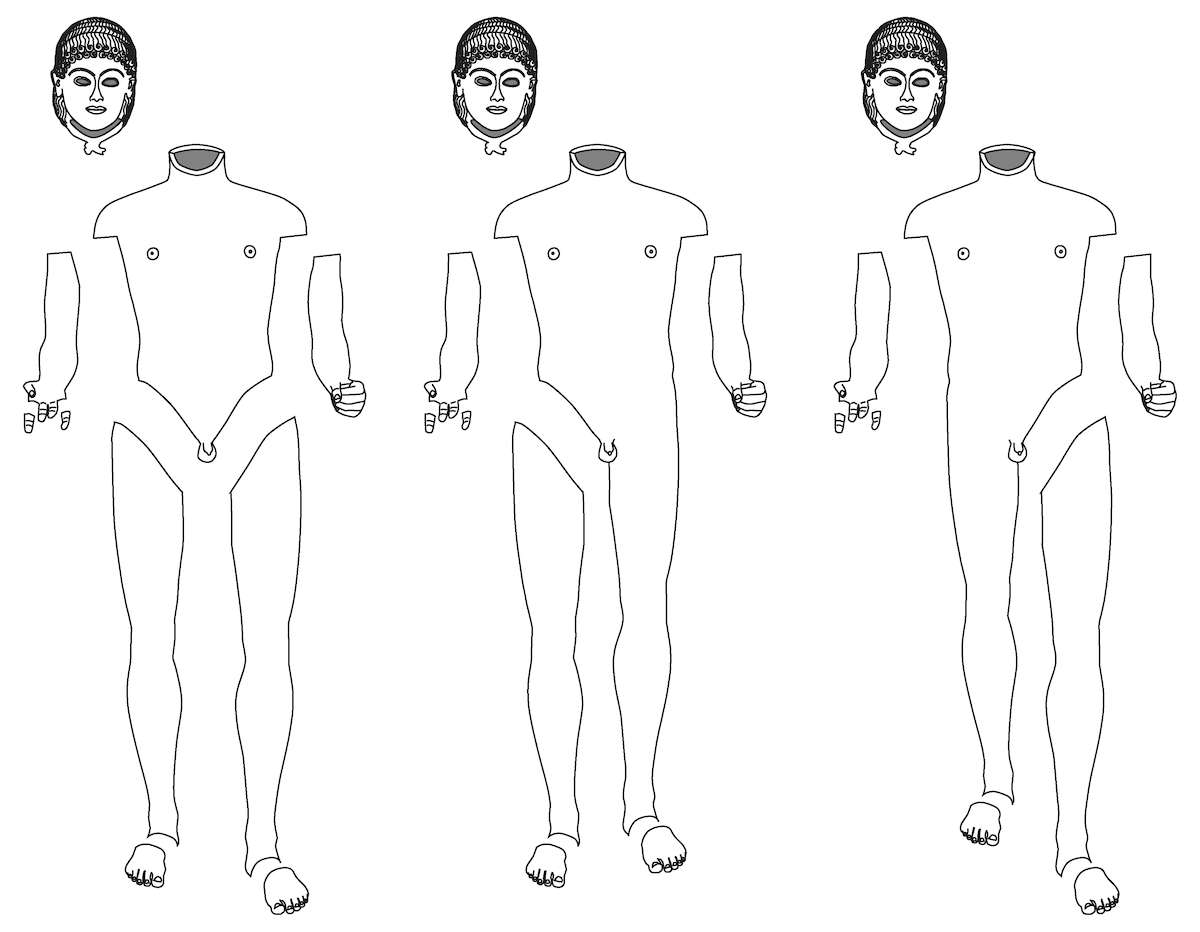

Very detailed comparative studies are still required before a distinct Rhodian bronze technique can be defined. The next step for research will be to explore the possible Rhodian origin of other large bronze statues and to compare the Piombino Apollo with other bronzes coming (or supposedly coming) from Rhodes or its vicinity. More works have to be investigated, in order to associate them, potentially, with the same production (fig. 42.9).26

Notes

- Descamps-Lequime 2015, no. 47, with related bibliography. ↩

- Lapatin 2015, no. 48. ↩

- Mattusch 1996a, 139–40, plates 5–6. ↩

- Queyrel 2012, 67–68. ↩

- Badoud 2010, 137–38; Badoud 2015, 281, no. 105. ↩

- Badoud 2015, 281, 285, 430–31, nos. 99, 103. ↩

- Badoud 2017. ↩

- Rhodes, Archaeological Museum, inv. E. 127; Konstantinopoulos 1977, 83, no. 137, fig. 119. ↩

- This examination was part of the workshop “Originaux, répliques et pastiches: Techniques d’élaboration et datation des grands bronzes antiques,” held in Paris on February 13, 2013; to be published in 2017. ↩

- For a similar analysis, see Bourgarit and Mille 2003. ↩

- The lighter gray shade that appears in the X-ray of the legs area is linked to a modern restoration filling. ↩

- Analogous wax-to-wax joins are visible on X-radiographs of the Child Dionysos (Mattusch 1996b, 240–41, fig. 26c), the Salamis Youth (Heilmeyer 1996, plate 20), and the Eros from Agde (Mille et al., 2012, fig. 14). ↩

- The number and placement of the cuts is the choice of the bronze caster. It depends partly on his ability to cast large pieces and manufacture complex molds and sprue systems, and partly on his mastery of efficient joining processes. ↩

- Azéma et al. 2011. ↩

- Examples of welding in basins are far too numerous to be cited here. See the Riace bronzes for fifth-century BC examples (Formigli 1984, fig. 24) and the horse from Neuvy-en-Sullias for a later Imperial one (Mille 2007). ↩

- For joining heads: drawing, explanation of the technique, and known examples in Mille et al. 2012, sections 44 and 49, figs. 17–20, 23–24, nos. 62–63. For legs, see Azéma et al. 2012, 156–59 and figs. 2, 4. ↩

- Azéma 2013, 143. ↩

- Goodlett 1991, 673. ↩

- Dow 1941, 358: the author proposed that the two names were those of the restorers who repaired the statue. If so, this would have meant that the eye sockets were already empty at the time of the restoration. More probably and as usual, the verb form “ἐποίῃσαν” was used to designate the sculptors who conceived the statue. ↩

- Ridgway 1996, 129. ↩

- Statue of Eros Sleeping (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 43.11.4): Hemingway 2015a; Portrait Statue of an Aristocratic Boy (idem. inv. 14.130.1): Hemingway et al. 2002; Hemingway 2015b. In Berlin, Statue of a Boy Athlete (Praying Boy), Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. Sk 2: Zimmer and Hackländer 1997; Mattusch 1998, 149–50. On bronze fragments of different statues, see Zimmer and Bairami 2008, 99–107, plates 2–6. ↩

- Mattusch 1998; Zimmer and Bairami 2008, 208–10. ↩

- Mattusch 1998, 156: “We have no evidence for a Rhodian ‘school’ of sculptors, but we have plentiful evidence for a Rhodian sculptural industry.” ↩

- See above n. 21. ↩

- Zimmer and Bairami 2008, 208. ↩

- Such as the group of Eros and Psyche, Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, inv. no. Br 4105 (see fig. 42.9). ↩

Bibliography

- Azéma 2013

- Azéma, A. 2013. “Les techniques de soudage de la grande statuaire antique en bronze: étude des paramètres thermiques et chimiques contrôlant le soudage par fusion au bronze liquide.” Thèse de doctorat, Université Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris 6).

- Azéma et al. 2011

- Azéma, A., B. Mille, P. Echegut, and D. De Sousa Meneses. 2011. “An Experimental Study of the Welding Techniques Used on the Greek and Roman Large Bronze Statues.” Historical Metallurgy 45(2): 71–80.

- Azéma et al. 2012

- Azéma, A., B. Mille, F. Pilon, J.-C. Birolleau, and L. Guyard. 2012. “Étude archéométallurgique du dépôt de grands bronzes du sanctuaire gallo-romain du Vieil-Évreux (Eure).” Archéosciences 36: 153–72.

- Badoud 2010

- Badoud, N. 2010. “Une famille de bronziers originaires de Tyr.” ZPE 172: 125–43.

- Badoud 2015

- Badoud, N. 2015. Le temps de Rhodes: Une chronologie des inscriptions de la cité fondée sur l’étude de ses institutions. Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Badoud 2017

- Badoud, N. 2017. “La lame de plomb découverte à l’intérieur de l’Apollon de Piombino.” In Originaux, répliques et pastiches: Techniques d’élaboration et datation des grands bronzes antiques (Paris, Musée du Louvre-C2RMF, February 13, 2013), ed. S. Descamps-Lequime and B. Mille. Technè 45.

- Bourgarit and Mille 2003

- Bourgarit, D., and B. Mille. 2003. “The Elemental Analysis of Ancient Copper-based Artefacts by Inductively-Coupled-Plasma Atomic-Emission-Spectrometry (ICP-AES): An Optimized Methodology Reveals Some Secrets of the Vix Crater.” Measurement Science and Technology 14: 1538–55.

- Daehner and Lapatin 2015

- Daehner, J. M., and K. Lapatin, eds. 2015. Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Exh. cat. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum. Florence: Giunti; Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Descamps-Lequime 2015

- Descamps-Lequime, S. 2015. “Statue of Apollo (Piombino Apollo).” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 288–91, no. 47.

- Dow 1941

- Dow, S. 1941. “A Family of Sculptors from Tyre.” Hesperia 10: 351–60.

- Formigli 1984

- Formigli, E. 1984. “La tecnica di costruzione delle statue di Riace.” In Due Bronzi da Riace: Rinvenimento, restauro, analisi ed ipotesi di interpretazione 1–2, ed. L. Vlad Borrelli and P. Pelagatti, 107–42. Bollettino d’Arte, serie speciale 3. Rome: Libreria dello Stato.

- Goodlett 1991

- Goodlett, V. C. 1991. “Rhodian Sculpture Workshops.” AJA 95: 669–81.

- Heilmeyer 1996

- Heilmeyer, W.-D. 1996. Der Jüngling von Salamis: Technische Untersuchungen zu römischen Großbronzen. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Hemingway 2015a

- Hemingway, S. 2015. “Statue of Eros Sleeping.” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 228–29, no. 20.

- Hemingway 2015b

- Hemingway, S. 2015. “Portrait Statue of an Aristocratic Boy.” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 260–61, no. 35.

- Hemingway et al. 2002

- Hemingway, S., E. Milleker, and R. E. Stone. 2002. “The Early Imperial Bronze Statue of a Boy in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A Technical and Stylistic Analysis.” In I Bronzi Antichi: Produzione e tecnologia: Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale sui Bronzi Antichi, Grado-Aquileia, 22–26 maggio 2001, ed. A. Giumlia-Mair, 200–207. Monographies instrumentum 21. Montagnac: Editions Monique Mergoil.

- Konstantinopoulos 1977

- Konstantinopoulos, G. 1977. Musées de Rhodes. Vol. 1: Musée archéologique. Athens: Apollo.

- Lapatin 2015

- Lapatin, K. 2015. “Statue of Apollo (Kouros).” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 292–93, no. 48.

- Mattusch 1996a

- Mattusch, C. C. 1996. Classical Bronzes: The Art and Craft of Greek and Roman Statuary. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Mattusch 1996b

- Mattusch, C.C. 1996. The Fire of Hephaistos: Large Classical Bronzes from North American Collections. Exh. cat. Cambridge (MA), Harvard University Art Museums.

- Mattusch 1998

- Mattusch, C. C. 1998. “Rhodian Sculpture: A School, A Style or Many Workshops?” In Regional Schools in Hellenistic Sculpture: Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, March 15–17, 1996, ed. O. Palagia and W. Coulson, 149–56. Oxbow Monograph 90. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Mille 2007

- Mille, B. 2007. “Étude technique du cheval de bronze de Neuvy-en-Sullias.” In Le cheval et la danseuse: À la redécouverte du trésor de Neuvy-en-Sullias, ed. C. Gorget and J.-P. Guillaumet, 88–99, 264–65. Paris: Somogy; [Orléans]: Musée des beaux-arts d’Orléans; [Bavay]: Musée/site d’archéologie.

- Mille et al. 2012

- Mille, B., L. Rossetti, and C. Rolley. 2012. “Les deux statues d’enfant en bronze (Cap d’Adge): Étude iconographique et technique.” In Bronzes grecs et romains: Recherches récentes: Hommage à Claude Rolley (Actes de colloque, INHA, 16–17 juin 2009), ed. M. Denoyelle, S. Descamps, B. Mille, and S. Verger. http://inha.revues.org/3949

- Queyrel 2012

- Queyrel, F. 2012. “L’Alexandre d’Agde: Un porte-plateau ou un porte-flambeau.” In De l’Éphèbe à l’Alexandre d’Agde, 61–69. Agde: Musée de l’Éphèbe & d’Archéologie sous-marine.

- Ridgway 1996

- Ridgway, B. S. 1996. “Roman Bronze Statuary: Beyond Technology.” In Mattusch 1996b, 122–37.

- Zimmer and Hackländer 1977

- Zimmer, G., and N. Hackländer. 1977. Der Betende Knabe: Original und Experiment. Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang.

- Zimmer and Bairami 2008

- Zimmer, G., and K. Bairami. 2008. Ροδιακά εργαστήρια χαλκοπλαστικής (Rhodian Bronze Workshops). Athens: TAPA.