39. Conservation Treatments and Archaeometallurgical Insights on the Medici Riccardi Horse Head

- Nicola Salvioli, Conservator, Florence

- Stefano Sarri, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze

- Juri Agresti, Istituto di Fisica Applicata “N. Carrara,” Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Florence

- Iacopo Osticioli, Istituto di Fisica Applicata “N. Carrara,” Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Florence

- Salvatore Siano, Istituto di Fisica Applicata “N. Carrara,” Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Florence

Abstract

History of the Artifact

The equine bronze protome known as the Medici Riccardi horse head in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Florence is likely a surviving part of a Hellenistic life-size equestrian sculptural group, which has been dated around the second half of the fourth century BC.1 The sculpture entered the antiquarian collections of the Medici in the fifteenth century and was cited for the first time in 1495 as part of Lorenzo il Magnifico’s antiquarian collection,2 although it had certainly been found well before that. Its close resemblance to the colossal Carafa horse head in Naples, executed by Donatello between 1456 and 1458 in imitation of this original, provides an indirect terminus ante quem.

The head is also cited in the Confiscation Decree by the Republican Government as being among the artifacts of the garden of the Palazzo Medici. Between 1495 and 1512 it was in Palazzo Vecchio (perhaps in the Cortile della Dogana); then it returned to the aforementioned garden,3 where it was admired by Lorenzo Bernini in 1665.4 In 1672 the artwork was restored and adapted as a fountain mouth by Bartolomeo Cennini.5

After being moved to Palermo in 1800 in order to avoid confiscation by Napoleon,6 the head returned to Florence in 1815, when it was displayed at the Galleria degli Uffizi.7 Finally, in 1890, it was transferred to the Regio Museo Archeologico, now the Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Florence.

State of Conservation

Before the recent cleaning treatments, the sculpture appeared rather dark and many of its details were obscured by a complex superposition of random materials (fig. 39.1). A sequence of irregular material levels was recognized within the stratification using portable Raman spectroscopy. Beeswax and oily substances applied in maintenance treatments; residues of calcareous growths (due to the use of the sculpture as a fountain mouth); and underlying corrosion layers (Cu-carbonates on tenorite and cuprite) were identified along with some residues from molding operations made using gypsum or silicone rubber.

Widespread calcareous growths were present on both the outer and inner surfaces. On the inside, these growths descended behind the eyes and the forehead just below the tuft (fig. 39.2a), which likely hosted the fountain pipe. Accumulations on the outer surface were mainly concentrated on the frontal part and skinfolds (fig. 39.2), while a smaller amount was present on the neck. However, before the sculpture entered museum collections, the outer calcareous encrustations were probably roughly removed using mechanical tools and just a small amount of residue was left flattened on the metal surface. Tool marks and deep scratches associated with this cleaning are evident, along with marks of sharp blades, rhomboidal tips of darts, or arrows—concentrated on the head but also present elsewhere (see for example fig. 39.2b)—which can be linked to the ancient vicissitudes of the artwork.

In various areas, traces of gilding were found. Analysis by scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDX) of some minute fragments of this gilding (fig. 39.3) allowed assessment. Results showed it to be a very thin (not more than a few microns), irregular gold film, which was well adhered to the underlying corrosion products (see fig. 39.3a). No traces of glue or mercury amalgam were found (the gold is pure). This, along with the imprint of the inner side of the gold leaf produced by the texture of the bronze surface (see fig. 39.3b), suggests it was likely applied using heat and mechanical means. The residual leaf fragments are very fragile and required special attention during the cleaning operations in order to safeguard this important evidence of decoration.

Conservation Intervention

The recent restoration was mainly aimed at removing aggressive exogenous substances and recovering the complete legibility of the object. The intervention was carried out in a dedicated room of the archaeological museum between January and March 2015. Visitors had the opportunity to see most of the intervention, though the use of dangerous substances and noisy tools was restricted to closed periods.

After preliminary material removal tests, which were carried out in order to optimize the treatment, the following operational sequence was performed on the outer surface, leaving the interior untouched.

Removal of powder and of the outer layer of the aged protective organic materials by washing the surface using cotton pads soaked in a solvent blend of petroleum ether (80–120°C) and methyl ethyl ketone (75/25 volume ratio).

Application of agar gel supporting an aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate with pH8. The application time was 4–7 minutes, which was sufficient for softening and saponification of the oleo-waxy superposition.

Removal of the agar gel and softened materials using soaked pads as in step 1.

Repetition of the washing treatment reinforced with a blend of cyclohexane and butyl acetate using a volume fraction of 55/45, respectively. This made it possible to safely expose the oxidized bronze surface and residual calcareous spots by safeguarding the traces of gilding (fig. 39.4a–b).

Exposed calcareous spots were removed using a piezoelectric ablator and sharp tools such as metal tips, wooden sticks, and porcupine spines. The surface was then homogenized using plastic-bristle brushes.

Protection with microcrystalline wax (1% in petroleum ether at 140–180°C), which is reversible and easily replicable, and finishing using natural-bristle brushes and cotton fabric. The general views of fig. 39.1b–c and the details of figs. 39.5–6 show the significant improvement of legibility achieved.

Figure 39.4a

Figure 39.4a

Figure 39.4b

Figure 39.4b

In some areas, minor watercolor retouches were also needed in order to smooth the abrupt chromatic variation (in the area of the phalerae) or to veil calcareous residues trapped within the surface roughness. In a few cases, suitably pigmented microcrystalline wax was also used to fill microcraters and other irregularities of the surface.

A small rectangular area on the collar of the horse (left side), which includes the old inventory number (1639), was intentionally left untouched as a witness to the previous appearance of the protome.

The present restoration also provided the opportunity to create a new mechanical support and to recover a more natural anatomical posture for the protome relative to its previous display. The structure was designed using 3D simulations and crafted using steel. This support was intended as a temporary solution for the exhibition Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World, allowing for a better view of the object and easy movability. However, the new support is also suitable for installation on the previous eighteenth-century pedestal.

Notes on the Sculptural Subject

The treatment described above recovered some of the original expressive strength of the Medici Riccardi horse head, with its pronounced realism and minimal use of stylization. Such a precise naturalism is not observed in other ancient bronze horses.

Unfortunately, despite the many studies of ancient horses, the surviving part of the original artwork does not allow us to determine the equine race of the horse or even whether it was pulling a chariot or mounted by a rider. We can only say that the horse was well proportioned, since the length of its head (65 cm from the forehead to the muzzle) relative to the neck (80.5 cm from the poll to the withers) is quite realistic. The right side of the protome shows the powerful, tense muscular structure of the neck terminating at the poll with a realistic muscle bulge, which makes more evident the link between the buzz-cut mane, the combed tuft, and the ears. The latter with their dense internal hairs are well proportioned and oriented in opposite directions: the right ear is directed forward at full attention, while the left is turned and tilted back, which suggests that the original sculptural theme was highly dynamic. Apart from the latter peculiar detail, the expressive tension of the subject and its formal solution recall the two small prancing horses of Herculaneum found in the area of the theater during the Bourbon excavations of the second half of the eighteenth century.8

The structural equilibrium of the forehead, temples, and eyebrow arch was certainly useful in accentuating the eyes (which were likely made using nonmetallic materials) and the direction of the gaze, while the relatively thin nose—with nostril dilated by impetuous breath—reinforces the notion that the object was conceived as part of a very dynamic ensemble.

The open mouth and the retracted tongue allow us to see the short teeth, which are typical of a young horse at the height of its strength. The energy that the animal holds back is also evidenced by the veins bulging all over the muzzle and the tense head. The head and neck are turning to the left, where there are more skinfolds on the throat and lips than on the corresponding right side. Thus the reins could have been stretched from the left side at the height of the withers or around the middle zone of the neck, which corresponds to the typical position of a rider’s hands.

Technical Examination

Various surface textures and chromatic features provide at first glance evidence of two different periods of the artwork’s life. Greenish mineralizations are observable all over the head and the upper part of the neck (those of the left side appear relatively irregular, due to interment conditions and previous invasive cleaning treatments), which shade toward the lower part of the neck; there, the modern integrations resulted in changes of color from red to brown to black. A number of losses were repaired with modern additions, including a large missing area at the left side, the entire collar (including its front banderole), which is partially superimposed on the ancient metal, and the upper part of the right ear. Furthermore, integrations are recognizable on the muzzle in the form of three recastings. Both ears were cropped in the past, and only the right one arrived to us restored, whereas the left only includes an internal uncorrelated repair. A number of intentional cuts, along with the extensive damage to the left side and the evident marks of weapons, indicate that the original sculpture likely was vandalized by being beheaded near the typical neck joint of bronze horses.

The aforementioned integrations were executed mainly by means of recasting, which involved significant heating of the original part and then the formation of a significant amount of cuprite and tenorite by redox reactions. Similarly, the subsequent cold smoothing of the patches and collar were extended to the adjacent original parts. However, the final result of this restoration remains technically rather far from the richness of detail and quality of the original, including precise casting and fine chasing of the whole surface. The ancient bronzesmiths lavished particular attention on the finishing of the mouth, the skinfolds, and the hair of the tuft and mane, which also include dense punch work between the two levels of locks achieved using a triangular punch.

The repairs, as well as the two functional holes in proximity of the withers (see the dark spots in fig. 39.1), which were likely needed to adapt the sculpture as a fountain, have to be attributed to the restoration by Bartolomeo Cennini in 1672.

The crownpiece, eyes, upper terminal of the tuft, and reins are missing. The former likely included nine phalerae whose position is evident from the set of large plugs and surface abrasions corresponding to the holes where the ancient anchoring elements of the phalerae were secured. There is also evidence of soft soldering along a linear stretch of the left cheek.

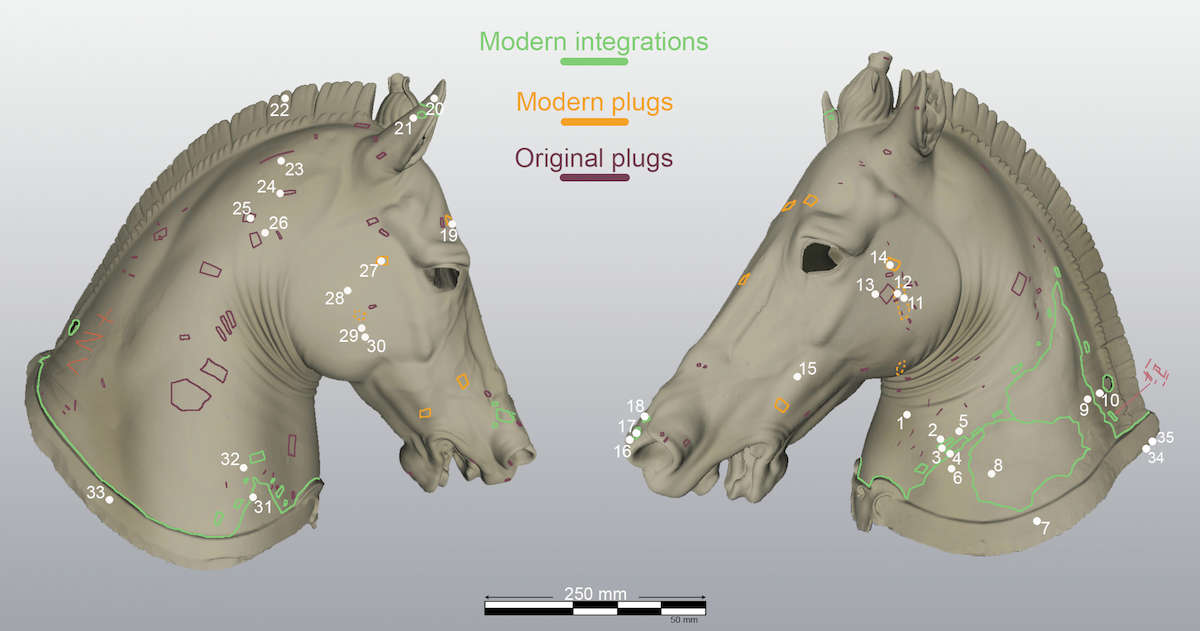

All the relevant technical features were precisely mapped on the 3D model of the outer surface, which was achieved using a range camera (Artec Eva) and suitable software. As shown in fig. 39.7, the contours of the modern integrations of the protome, including a number of plugs, were recognized. Most of them are randomly distributed, whereas the nine associated with the phalerae are arranged regularly along the missing metal strips of the crownpiece.

The tongue was likely executed by means of a casting-on operation, as suggested by its close proximity to the surrounding part of the mouth.

Apart from the areas of the modern integrations of the neck, the inner surface of the protome is relatively smooth, roughly reproducing the exterior, and does not exhibit any traces of wax joins. Minor reliefs, such as those of the locks of the mane, present corresponding modulations of the inner surface (fig. 39.8). This suggests that the wax model was formed using liquid wax. However, the lack of satisfactory radiographic data (only a few unclear images are available from the investigation of the 1990s9), the apparently strange imprint observed at the inner surface of the mane where its shape is rather sharp, and other features led us to a detailed interpretation of the preparation procedure of the wax model for casting.

Both interior and exterior surfaces were scanned and digitally reconstructed. These two 3D models were merged by exploiting the visible cross-section of the neck, thus achieving a complete volume model of the bronze wall that allowed examination of its thickness. Figure 39.9 summarizes some meaningful cross sections, such as those of the front (fig. 39.9b), the neck (fig. 39.9c), and the mane (fig. 39.9d–e). The front shows moderate thickness variations and then a good correspondence between the outer and inner profiles of the right side and mane (original parts), while more pronounced thickness variations are observed in the mane. However, the mane also shows the congruence between reliefs and indentations, although the thickness variations observed are significant; note for example that in fig. 39.9e, the left side is much thicker than the right at the upper zone. This observation, along with the sharp crest of the mane at the inner surface (fig. 39.9b), led us to consider the possibility of significant direct modeling work. However, the aforementioned features depend on many material parameters, such as possible thinning during the finishing of the wax model; the possible differences in terms of mineralization and encrustation of the two inner sides of the mane; the type of wax; and the casting process. After a critical evaluation of the data collected, we conclude that the present protome was executed according to the typical copy process wherein the wax replica was made by slush casting and direct finishing.10 The detail reported in fig. 39.8, showing the very smooth internal undulation of the right side of the head and the thickness profiles of figs. 39.9b–c, seem convincing evidence of slush casting. Probably the cleaning of the internal surface or a detailed radiographic examination would also bring to light the drips that were expected but not observed in the present study.

For the sake of completeness, let us also observe that the radiographic images collected during the investigation of the 1990s11 show a very straight wax join in proximity to the terminal part of the muzzle. Assuming this is not an accidental effect, it could be interpreted as a consequence of an intentional cut into the wax needed in order to build and dry the core structure.

Chemical Analysis of the Alloys

The alloy compositions were thoroughly investigated using laser induced plasma (or breakdown) spectroscopy (LIPS or LIBS). In this noninvasive technique, short laser pulses are focused on the material of interest, and its elemental weight fractions are derived through the spectral analysis of the bright plasma plumes generated at the laser focus.12 In some details a compositional depth profile is collected along typical depths of several hundred microns; then the bulk composition is derived by averaging the concentrations of the deeper part of this profile. (This innovative approach has also been exploited to study the Chimaera of Arezzo.13) The measurement points are mapped in fig. 39.7 (white numbers and dots), and the corresponding results are listed in table 39.1. Two distinct type of bronze alloys were measured using LIPS, with the following average compositions: (1) tin 11 wt%, lead 1.0 wt%, trace of iron for the main casting (most of the protome); (2) tin 4.3 wt%, lead 2.4 wt%, nickel 1.5 wt%, traces of zinc and iron for repairs already preliminarily attributed to the Cennini restoration, including the integration of the left side (main recasting), the collar, and the plugs closing the anchoring holes of the phalerae (measured sites: 14, 19, and 27). By contrast, the plugs corresponding to sites 24 and 25 have an alloy similar to the main one and are hence interpretable as ancient repairs.

| Site | Sn (wt%) | Pb (wt%) | Zn (wt%) | Ni (wt%) | Fe (wt%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Throat (f) | 11.8 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | Main alloy |

| 5 Neck (l) | 11.8 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | |

| 13 Cheek (l) | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | - | - | 0.1 ± 0.05 | |

| 15 Muzzle (l) | 10.9 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | - | - | 0.13 ± 0.04 | |

| 16 Muzzle (f) | 10.8 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | - | - | 0.15 ± 0.05 | |

| 21 Ear (r) | 10.7 ± 1.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | - | - | 0.13 ± 0.05 | |

| 22 Mane (u) | 11.0 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | |

| 23 Neck (r) | 11.3 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | - | - | - | |

| 26 Neck (r) | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | - | - | 0.12 ± 0.05 | |

| 28 Cheek (r) | 11.3 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | - | - | 0.14 ± 0.04 | |

| 29 Cheek (r) | 11.3 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | - | - | 0.07 ± 0.03 | |

| 30 Cheek (r) | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | - | - | 0.1 ± 0.05 | |

| 30 Chest | 10.8 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | - | - | 0.12 ± 0.04 | |

| 35 Collar (inner) | 11.4 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | - | - | - | |

| 10 Mane (l) | 16.0 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | Visible residues of tin used to solder the crownpiece |

| 11 Tin (l) | 35.4 ± 3.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | - | - | 0.13 ± 0.04 | |

| 12 Tin (l) | 29.1 ± 3.7 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | - | - | 0.14 ± 0.05 | |

| 2 Anchoring (l) | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.07 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | Repair patches by recastings |

| 3 Anchoring (l) | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | - | 1.4 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 4 Main recasting (l) | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.06 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | |

| 6 Minor patch (l) | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | - | 1.6 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 4 Collar (outer l) | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | - | 1.4 ± 0.1 | - | |

| 8 Minor patch (l) | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 9 Main recasting (l) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.14 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 17 Muzzle repair (f) | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 18 Muzzle repair (f) | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | |

| 20 Ear repair (f) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 31 Main recasting (f) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | - | 1.5 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 33 Collar (r) | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | - | 1.5 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 34 Collar (outer l) | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | - | 1.7 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 24 Plug (r) | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | Ancient plugs |

| 25 Plug (r) | 11.7 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | |

| 14 Phalerae plug (l) | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | - | 1.6 ± 0.2 | - | Plugs corresponding to the anchoring holes of the phalera |

| 19 Phalerae plug (r) | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | - | |

| 27 Phalerae plug (r) | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | - | 1.2 ± 0.1 | - |

The coherence of the modern integration and plugs is very strong: besides having a similar amount of tin and lead, the relatively high nickel content and the frequent traces of zinc are very significant. These data are in substantial agreement with those reported by De Marinis (1998).

Conclusions

The present conservation treatments carried out on the Medici Riccardi horse head recovered the realism and dynamism of the original part of the sculpture and allowed to us to uncover and safeguard minute traces of gilding all over the artwork. These elements were previously obscured by waxy patinations, calcareous growths, and deposits. The formal features and the details of the protome are now more legible, while the modern repairs have been made more evident than before.

The gilding traces uncovered are much greater than expected. The widespread presence of gold-leaf microfragments among the skinfolds; on the throat, mane, and tongue; in the ears; and elsewhere, along with the lack of a mordant, prove that the head was gilded in ancient times. The former presence of a crownpiece with phalerae is also evident. Thus, we believe the reconstruction of fig. 39.10 is reliably supported by the present data. Most of the gold leaf was lost due to the burial conditions, the use of the sculpture as a fountain, and the aggressive mechanical and chemical cleaning treatments, which eroded the surface.

The archaeometallurgical study also allowed us to identify all the additions introduced during the seventeenth-century restoration by Bartolomeo Cennini. The data show the main alloy is very close to the conventional 90–10 (here Sn 11 wt% and Pb 1 wt%) traditionally used for large bronzes from the Classical period and up to the Roman Republican period. Examination of the metal wall thicknesses through the virtual sectioning of the double surface-3D model provided important evidence about the wax model for casting and definitively demonstrated indirect casting.

Acknowledgments

The conservation project and archaeometallurgical investigation of the Medici Riccardi horse head was funded by the Friends of Florence, a U.S. 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization supported by individuals who are dedicated to preserving and enhancing the cultural and historical integrity of the arts in the city and surrounding area of Florence, Italy.

Notes

- Cianferoni 2015; Borrelli 1992, 67; Coarelli 1981, 246 n. 88. ↩

- Borrelli 1992, 67: “la cosiddetta testa Medici-Riccardi, che figura già fra i beni confiscati a Piero de’ Medici nel 1495, e quindi dovette appartenere a Lorenzo il Magnifico.” ↩

- Cianferoni 2015. ↩

- Baldinucci 1812, 91: “… oltre alla meravigliosa testa, e collo di bronzo del cavallo, che per comun parere, e dicesi anche per sentenza dello stesso Bernino, è della stessa mano di quegli, che fece il famoso cavallo di Campidoglio” ↩

- De Marinis 1998, 283. ↩

- Romualdi 1996. ↩

- Pasquinelli 2008. ↩

- In particular the riderless horse with the head turned to left: Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 4894. ↩

- De Marinis 1998, 288–94. ↩

- In addition to refining the minute details of the sculpture, a correction of the curvature and folds of the right side was also probably performed, as suggested by some signs of manual shaping. ↩

- De Marinis 1998, 288–94. ↩

- Agresti, Mencaglia, and Siano 2009. ↩

- For further details on the technique, see Siano et al. 2012. ↩

Bibliography

- Agresti, Mencaglia, and Siano 2015

- Agresti, J., A. A. Mencaglia, and S. Siano. 2015. “Development and Application of a Portable LIPS System for Characterising Copper Alloy Artefacts.” Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 395 (7): 2255–62.

- Baldinucci 1812

- Baldinucci, F. 1812. Notizie dè Professori del Disegno da Cimabue in quà Firenze, 1681–1728. Milan: Società Tipografica dè Classici Italiani.

- Borrelli 1992

- Borrelli, L. V. 1992. “Considerazioni su tre problematiche teste di cavallo.” Bollettino d’Arte 71 (ser. 6): 67–82.

- Cianferoni 2015

- Cianferoni, G. C. 2015. “Horse Head (Medici Riccardi Horse).” In Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World, ed. J. M. Daehner and K. Lapatin, 190–91, no. 3. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; Florence: Giunti.

- Coarelli 1981

- Coarelli, F. 1981. “Alessandro, i Licini e Lanuvio.” In L’Art decoratif à Rome: À la fin de la Republique et au dèbut du Principat, 229–84. Collection de l’Ècole Francaise de Rome 55. Paris: Ècole Francaise de Rome.

- De Marinis 1998

- De Marinis, G. 1998. “La protome di cavallo Medici-Riccardi: Il contributo delle indagini chimico-fisiche.” In In memoria di Enrico Paribeni, ed. G. Capecchi, O. Paoletti, C. Cianferoni, A. M. Esposito, and A. Romualdi, 281–94. Rome: Giorgio Bretschneider.

- Pasquinelli 2008

- Pasquinelli, C. 2008. La Galleria in Esilio: Il trasferimento delle opere d’arte da Firenze a Palermo a cura del Cavalier Tommaso Puccini (1800–1803). Pisa: ETS.

- Romualdi 1996

- Romualdi, A. 1996. “La testa di cavallo Medici Riccardi.” In Bronzi greci e romani dalle collezioni del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, ed. A. Rastrelli and A. Romualdi, 8. Exh. cat. Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze.

- Siano et al. 2012

- Siano, S., M. Miccio, M. Giamello, S. Mugnaini, and J. Agresti. 2012. “Journey through the Material Layers of the Chimaera from Arezzo.” In Myth, Allegory, Emblem: The Many Lives of the Chimaera of Arezzo, ed. G. C. Cianferoni, M. Iozzo, and E. Setari, 185–222. Rome: Aracne.