|

||

What Is an Illuminated Manuscript?

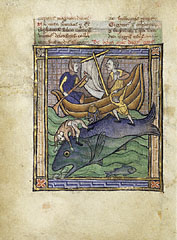

Illuminated manuscripts are books written by hand and painted with precious pigments. Manuscripts contain most of the finest surviving examples of medieval painting. The word manuscript is derived from the Latin words manus (hand) and scriptus, from the verb scribere (to write). Today the term is used to describe any handwritten text. The word illumination comes from the Latin verb illuminare (to light up), which, in this context, describes the glow created by the radiant colors of the illustrations, especially gold and silver. Illumination took the form of decorated letters, borders, and independent painted scenes, called miniatures.

Manuscripts were most often written on parchment, a high quality writing support made from the specially prepared skins of calves, sheep, or goats. Although paper could be found in Europe as early as the 14th century, parchment continued to be used for several hundred years in spite of the greater cost involved. Its beautiful texture and translucency, its ability to withstand the wear and tear of daily handling, and its resistance to the dissolving action of acidic inks were among the qualities that made parchment so appealing.

Learn how Medieval manuscripts were made, from the exhibition The Making of a Medieval Book.

|

||

The miniatures were painted with a variety of colors, including vermilion and ultramarine blue, and were often decorated with gold leaf. The pigments used in illumination consisted of vegetable, mineral, and animal extracts, which were ground up or soaked out. Vermilion was made from mercury and sulfur, while ultramarine blue, a pigment as expensive as gold, was created by crushing lapis lazuli. Gold leaf was applied to luxury manuscripts in thin sheets; in the later Middle Ages, however, artists substituted gold paint.

|

||

Makers and Materials

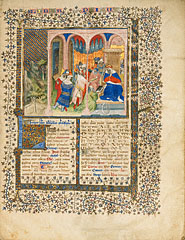

The most elaborate and beautiful illumination was devoted to religious works, which, until the rise of universities in the 12th century, were produced in monasteries. European intellectual life in the early Middle Ages was focused mostly in monasteries, many of which made copies of important books and writings (both Christian and classical) and formed their own libraries. In a monastery, the scriptorium was the center for both scholarly activity and the copying of texts. Later, lay artists were often hired to collaborate with monastic scribes.

Monastic scriptoria survived throughout the Middle Ages, but by the 12th century, scribes and illuminators were increasingly laymen who made their living by supplying fine manuscripts to noblemen, the new middle class, and the emerging universities in cities such as Paris, Bologna, and Oxford. Some religious communities also began copying manuscripts on a commercial basis.

By the 12th century, the production of a luxurious illuminated manuscript had been divided among four distinct craftsmen: the parchment maker, the scribe, the illuminator, and the bookbinder. Each was required to belong to a guild that had specific rules governing both the quality of work and the rights of its membership. The guilds also set standards and procedures for training apprentices. Frequently the guild maintained a monopoly over the rights of manufacture as well as the sale and price of goods. An independent middleman, usually an individual illuminator or a scribe, was responsible for coordinating the efforts of the four workshops involved in each commission.

The parchment maker prepared the animal skins used to make the leaves of a manuscript. The skins were soaked in a bath of lime to remove the hair. They were then stretched, scraped down, and rubbed with pumice. The final steps were to whiten the skins with chalk and cut them to size.

|

||

The scribe wrote the manuscript's text by hand. Scribes usually made their own quills and ink, just as illuminators prepared their pigments. To make the text appear in a consistent format throughout the manuscript, the scribe drew ruling lines on each page to establish the margins and the spaces between the lines.

The illuminator provided the manuscript's painted decoration. Illuminators and painters of large, freestanding panels were often members of the same guild and equally respected as artists. The number and variety of illumination in a single luxury manuscript often required the collaboration of several craftsmen, and the master of a workshop would often assign some miniatures, borders, and initials to assistants.

The bookbinder provided a binding to protect the manuscript, which held the leaves together and kept them from curling. Metal clasps or ties of leather or fabric were used to keep the manuscript closed. Bindings were sometimes embellished with paint or enamel or with designs stamped with metal tools; the most precious manuscripts were adorned with metalwork and jewels.