|

An exhibition for kids and families!

This exhibition focuses on the working method of artists in the Middle Ages (about A.D. 500–1500), when books were written and copied by hand. Visitors can explore medieval books from the Museum's collection and enjoy hands-on copying activities at a scriptorium table.

Scriptorium is a Latin word that means "place for writing." It was a place where books were copied and illuminated (painted).

A scribe wrote the text for a book, and an artist, called an illuminator, painted the pictures and decoration. Scribes and illuminators made each book by hand. Manuscripts (handmade books) were often written and illuminated by monks in monasteries.

Books were written on parchment made from the skin of sheep or goats. The animal skins were stretched and scraped so that they were smooth enough to write on. Precious materials, such as gold leaf and ground gemstones, were used to decorate the pages of manuscripts.

|

|

|

|

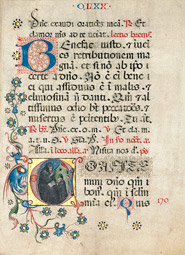

Diagram of a manuscript page

|

|

|

A page in an illuminated manuscript has three parts:

• a picture (called a miniature)

• words

• border decoration

The picture and the words tell the story. The border is usually decorative.

|

|

|

|

|

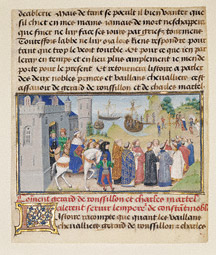

The French navy sets sail for battle on a page from the Chronicles, a history book made in the 1400s

|

|

Miniatures

Pictures in manuscripts are called miniatures, but not because they are small. The word "miniature" comes from minium, the Latin word for the red paint used in almost every picture. Miniatures illustrated stories and made manuscripts more beautiful.

The miniature on this page illustrates an episode in a history book that tells stories of the wars between England and France in the 1300s. Here the French navy sets sail for Castille, in Spain, to fight the English.

|

|

|

The Written Word

To create the text of a manuscript, scribes copied each word by hand from an existing book, and artists decorated important letters. The pages of a manuscript were ruled to help the scribes write straight lines.

A scribe used black and red ink to copy this page from a prayer book written in Latin, which was used by monks in church services.

The large decorated initials—a B at the top and a C below—mark the beginnings of new sections in the text.

|

|

|

|

|

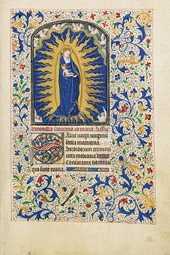

Border decoration on a page from the Arenberg Hours, a prayer book made in the 1460s

|

|

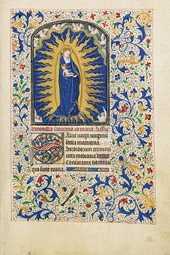

Border Decoration

Artists often adorned the borders of manuscript pages. Borders were mostly ornamental, and artists were free to be inventive when they decorated these spaces. Artists often illuminated borders with images of flowers, vines, insects, and other creatures.

Even though the Virgin and Christ child are the main subjects of this page, the artist dedicated almost as much space and attention to the border decoration as he did to the miniature.

|

|

|

Tradition was important for scribes and illuminators. For medieval artists, it was more important for a picture to be easily understood than to be original. However, medieval artists were creative in the ways they used pictures to tell a story.

|

|

|

Artists sometimes depicted the same people more than once in a single picture. This helped them tell different parts of a story in a single painting.

This page is from a history book about famous French kings. A court scribe dedicated the page to the story of future leader Charles Martel's voyage to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul).

The artist had only one small space to illustrate the journey, as well as Martel's welcome by the Byzantine emperor (shown wearing a blue cape and crown). The emperor is depicted twice: first leaving his palace, and later greeting Martel.

|

|

|

This page comes from a manual on hand-to-hand combat written by a famous fencing master. It was probably made for the Duke of Ferrara, one of the most powerful rulers in Italy.

This page explains different moves to use in combat with a dagger and a staff. The facing page shows aiming points on the body.

Throughout the book, the artist added a gold band to the leg of one of the two fighters to show the reader which fighter is demonstrating the action described in the text.

|

|

|

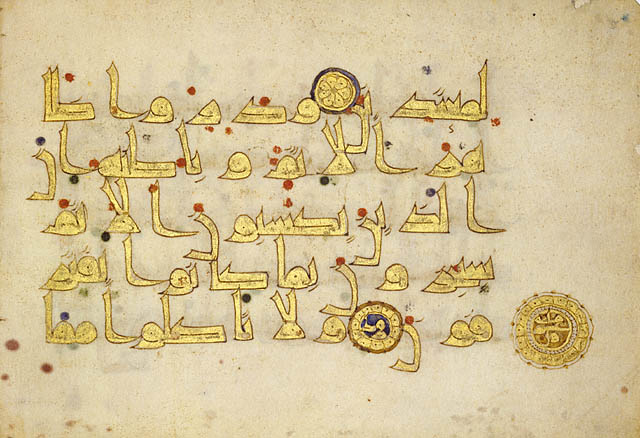

In the Middle Ages, manuscripts were illuminated throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Though written in different languages, stories were illustrated using the universal language of pictures. Artists from different countries often used the same characters, symbols, and compositions.

Islamic and Christian artists had different traditions when it came to decorating their holy books.

For example, Christian artists often illustrated their stories with pictures, while Islamic artists focused on embellishing the words themselves. But, as shown in the pages below, both cultures used gold to highlight the importance of the religious messages.

|

|

|

|

|