|

Peter Paul Rubens's Man in Korean Costume has been considered noteworthy since its creation in the early 1600s. This large-scale drawing, now in the Getty Museum's collection, was copied in Rubens's Antwerp studio during his own time and circulated as a reproductive print in Europe in the 18th century.

Despite the drawing's renown, why it was made and whether it actually depicts a specific person remain a mystery. This focused exhibition provides the first thorough investigation of this captivating work of art and the religious and mercantile contexts that fostered the artist's encounter with Asia. By situating the Getty drawing within the context of cultural history, this exhibition presents a broader understanding of what appears to be the earliest depiction of a Korean costume by a Western artist.

As an artist and diplomat working for rulers in courts across Europe, Rubens expressed his fascination with foreign costumes and headdresses. In this drawing, Man in Korean Costume, which depicts the attire of an Asian kingdom little known to him, Rubens lavished attention on the cascade of the shimmering folds and transparent hat. The man has been associated with Siamese ambassadors in London, pagan priests in Goa, European Jesuits in China, and most popularly a former Korean slave who traveled to Italy from Japan.

|

|

|

|

Portrait of Nicolas Trigault in Chinese Costume, 1617, Peter Paul Rubens. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Carl Selden Trust, several members of The Chairman's Council, Gail and Parker Gilbert, and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 1999.222. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image Source: Art Resource, NY

|

|

|

The Getty drawing, due to its size, media, and similar paper stock, has long been associated with four drawings depicting Jesuit missionaries working in China. By the late 16th century, members of the Catholic religious order called the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, were actively proselytizing in China, with which Korea had a tributary relationship. The Jesuits made little progress until they realized that a better way to convert the Chinese to Christianity would be to infiltrate the Ming dynasty's governmental structure. To this end, they mastered Chinese, donned the long silk robes and tall four-corner hats worn by Confucian scholars, and let their beards grow long.

This drawing is of Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628), the Jesuit leader of the Chinese mission. Rubens depicted Trigault in 1617 when the missionary traveled to Antwerp as part of his publicity campaign to raise funds and gather recruits for the Chinese mission. The artist articulated the voluminous folds of Chinese robes as well as the shimmer and sheen of the opulent silk fabric in a matter-of-fact manner. Seen as a group, these drawings demonstrate how the Jesuits used exotic costumes to advertise their global outreach and promote the magnificence of their missionary work.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

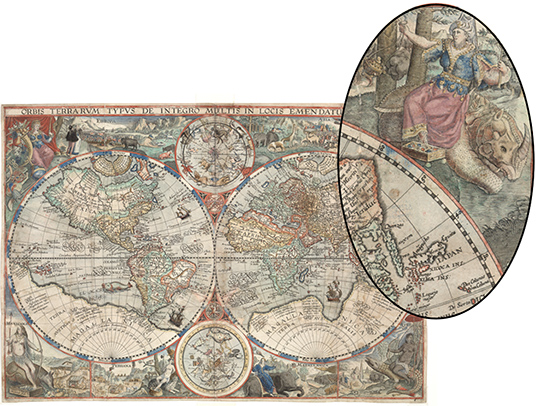

Orbis Terrarum (Map of the World) and inset of detail of Korea and personification of Asia, 1594, Petrus Plancius. Courtesy of and reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

|

|

|

|

|

|

When Rubens made his Man in Korean Costume, Korea was officially closed to the West and only indirectly linked to Europe through its East Asian neighbors. Korean diplomats came to China three times a year on average to pay tribute, which resulted in an extensive exchange of material goods between the two nations. This trade between the Chinese and Koreans took place in the capital of Beijing, where the Jesuits conducted their missionary work. Thus it is possible that Rubens's Jesuit patron Nicolas Trigault acquired Korean costume and headdresses in China and imported them back to Europe.

This colorful map of the world demonstrates an improved geographic knowledge of Korea in late 16th-century Europe. For the first time on a European map, Korea appears as a peninsula rather than unchartered territory or an island. Plancius's map also includes allegorical figures of the four continents. Asia, seen in the upper-right corner, wears a fanciful garment and headdress and brandishes an incense burner. She sits on a rhinoceros, which was introduced to Europe from the province of Assam in the early 16th century and has ever since been an animal associated with Asia.

|

|

|

|

Cheollik Excavated from the Tomb of Military Officer Byeonsu (1447–1524), early 1500s, Unknown. National Folk Museum of Korea 국립민속박물관. Image © National Folk Museum of Korea

|

|

|

Scholars of Korean costume associate Rubens's portrayal of luxurious silk garments and transparent headdress with the attire worn by high-ranking individuals of Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) Korea. It cannot be presumed, however, that the 17th-century Flemish artist's alluring depiction is mere documentation. Entirely removed from the culture to which the novel costume and headdress belonged, Rubens fashioned the foreign attire to his own liking. The artist's interpretation is noticeably different from traditional Korean clothing.

This robe is identified as a cheollik (pronounced chul-leek), a coat with long sleeves worn bunched up and a Y-shaped collar that tucks deeply underneath the arm at the left. The bodice and skirt of the cheollik are separate pieces sewn together at the waist, producing a uniform distribution of folds. In the Getty drawing, the inner coat bosts a hem of a uniformly wavy pattern and an underskirt indicative of a cheollik.

|

|

|

In 1617 the Jesuits in Antwerp commissioned Rubens to execute a monumental altarpiece promoting the miracles performed by missionary Saint Francis Xavier (1506–1552) in Goa (in present-day India). The artist first presented a smaller oil sketch modello (preparatory study) illustrating his compositional ideas. The modello shows a pagan priest wearing a Turkish turban and a caftan.

In the altarpiece, Rubens replaced Turkish costume with a variety of exotic attire, including silk robes and a transparent headdress similar to those depicted in the Getty drawing. While Rubens was glorifying the Jesuit mission in Goa, he paused to consider the Asian "idolators" on the other side of the globe: Who were these people the Jesuits were trying to convert to Catholicism and what did they look like? How did what they wear differ from what the Jesuit missionaries wore? Rubens's imaginative turn seems to have been inspired by a firsthand encounter with Korean costume and headdress.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|