| Education | ||

| Exhibitions | ||

| Explore Art | ||

| Research and Conservation | ||

| Bookstore | ||

| Games | ||

| About the J. Paul Getty Museum | ||

| Public Programs | ||

| Museum Home

|

July 12–November 5, 2007 at the Getty Villa

In 1711, workers digging a well in the small town of Resina, Italy, found three mostly intact marble statues of draped women. Heralding the discovery of ancient Herculaneum, the sculptures are known today as the Large and Small Herculaneum Women. |

||||||

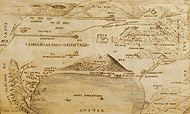

The Site of Herculaneum The ancient Roman city of Herculaneum is situated on the Bay of Naples in southwestern Italy (see map). The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79 buried the seaside town under layers of volcanic debris and mud that eventually hardened into rock. |

||||||

This bird's-eye view of Campania from the early 1500s represents an early effort to pinpoint the location of Herculaneum—marked here beneath the looming peaks of Vesuvius. |

||||||

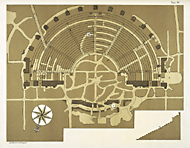

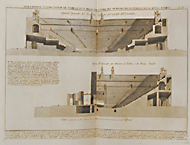

Discovering Herculaneum at the Dawn of Archaeology Early exploration of Herculaneum was motivated by the quest for ancient treasures to adorn the royal collections of the Bourbon monarch Charles III. The practice of random mining for antiquities gave way to a system of digging tunnels that followed the course of ancient building foundations. Both approaches can be seen in this first plan of Herculaneum's theater. |

||||||

Archaeological Context: The Theater When they were discovered, the Herculaneum Women were hoisted through a well shaft that led down to the remains of a Roman theater buried 75 feet below the street level of modern Ercolano. They probably once decorated the stage's impressive double-tiered façade, along with other sculptures of mythological and historical figures. |

||||||

Promotion and Controversy Under Charles III, who reigned from 1735 to 1759, the kingdom of Naples became renowned for its archaeological riches and fascinating geology. Imperial pride spurred the printing of officially sanctioned excavation reports and illustrated folios of antiquities. On this page from the first royal publication of ancient art from Herculaneum, Charles III poses as a sponsor of intellectual and cultural enlightenment. |

||||||

The Herculaneum Women in European Princely Collections Prince d'Elboeuf, whose workmen discovered the Herculaneum Women, presented the sculptures as a gift to Prince Eugene of Savoy in Vienna. The earliest illustrations of the Herculaneum Women, shown here, depict them among the exotic animals Eugene kept at his Belvedere Gardens. |

||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||