|

|

|

Fence, Truro, Joel Meyerowitz, 1976. Gift of Nancy and Bruce Berman. © Joel Meyerowitz, Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, NY

|

|

With its immensity, immateriality, and variability, the sky has been an enduring subject in art history, fascinating and challenging generations of artists.

As soon as the medium of photography was introduced in 1839, photographers attempted to represent the sky and its natural phenomena.

Atmospheric light and its constant mutability have always been hard to capture, but by the 1850s the greater light sensitivity of collodion negatives (compared to the daguerreotype and calotype processes) allowed the spectacles of the sky to be more easily transposed to photography.

With further technical improvements such as the development of instantaneous processes in the 1880s and the advent of Kodachrome color film around 1935, photographers have continued to explore this theme in diverse and imaginative ways.

|

|

|

|

Cloudy Sky—Mediterranean Sea, Gustave Le Gray, 1857

|

|

|

The collodion process (in which a syrupy, light–sensitive mixture was applied to glass–plate negatives) was advantageous for its short exposure time and sharpness, but its sensitivity to blue light could also pose a challenge. By the time the camera captured detail in the foreground, the sky was often overexposed and thus printed as blank space.

To create his sweeping seascape, Cloudy Sky— Mediterranean Sea, Gustave Le Gray combined two slightly overlapping negatives: one for the sky and one for the sea.

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled (Zuma Series), John Divola, 1977–78.

Gift of the Wilson Centre for Photography. © John Divola

|

|

In the fall of 1977, after discovering an abandoned lifeguard headquarters at Zuma Beach, California, John Divola began visiting the site to photograph. Painting the walls, incorporating props, using flash, and depending on the Pacific Ocean and the sky for a dramatic backdrop, he created a series of makeshift scenes.

Discussing his work in 1980, Divola said, "These photographs are the product of my involvement with an evolving situation. The house evolving in a primarily linear way toward its ultimate disintegration, the ocean and light evolving and changing in a cyclical and regenerative manner."

|

|

|

Robert Adams' landscape photographs tend to merge two disparate visions of the American West; they reveal problems brought on by population growth, suburban development, and highway construction and yet their formal beauty also implies nature's resilience.

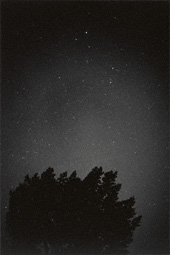

In a 2005 interview with the Getty Museum, Adams explained that the image West of Keota, Colorado was photographed from a religious site, Mother Cabrini's Shrine, located in the Denver–area foothills. It is part of a series entitled "Summer Nights." He used a tripod and a relatively short exposure of about 10 seconds, in order to avoid the stars registering as streaks across the sky.

Growing up in Denver, Colorado, Adams had always considered the American West as synonymous with space and quiet and sky. West of Keota, Colorado, captures that sensibility.

|

|

|

Soon after arriving in New York in October 1936, André Kertész spent time searching the city streets for fresh material, just as he had done in Paris for a decade. One afternoon he observed a solitary white cloud in a vast blue sky, dwarfed by the monolithic presence of the Rockefeller Center. Kertész later recounted that he was "very touched when he saw the cloud, as it "didnt know which way to go" (Bela Ugrin, Dialogues with Kertész, " 1978–85, the Getty Research Institute) — a sentiment he strongly identified with as a new immigrant.

From the lyrical to the abstract, photography has often been an apt medium with which to capture the fleeting nature of skies.

|

|