Underworld

Imagining the Afterlife

The Underworld was a shadowy prospect for most ancient Greeks, characterized primarily by the absence of life’s pleasures. Perpetual torment awaited only the most exceptional sinners, while just a select few—heroes related to the Olympian gods—enjoyed an eternal paradise. Yet as this exhibition explores, individuals did seek ways to secure a blessed afterlife. Initiation in the Eleusinian Mysteries, an annual festival in Greece, promised good fortune in both this world and the next. Outside of mainstream religious practice, devotion to the mythical singer Orpheus and the god Dionysos also offered paths to achieving a better lot after death.

Some of the richest evidence for ancient beliefs about the afterlife comes from southern Italy, particularly indigenous sites in Apulia and the Greek settlement of Taras (present-day Taranto). Monumental funerary vessels are painted with elaborate depictions of Hades’s realm, and rare gold plaques that were buried with the dead bear directions for where to go in the Underworld. These works, alongside funerary offerings, grave monuments, and representations of everlasting banquets, convey some of the ways in which the hereafter was imagined in the fifth and fourth centuries bc.

This exhibition was organized in collaboration with the National Archaeological Museum of Naples – Laboratory of Conservation and Restoration.

Download the exhibition object checklist

Join the curator on a walkthrough of the exhibition in this video.

Greek Beliefs about the Afterlife

Most ancient Greeks anticipated that the soul left the body after death and continued to exist in some form, but an expectation that good would be rewarded and evil punished in the afterlife was not central to their beliefs. In Homer’s Odyssey (750–700 bc) the Underworld—otherwise known as “the house of Hades,” or simply “Hades,” after the god who ruled over the dead—was bleak and somber for nearly everyone. Only a handful of mythical figures suffered for eternity, and their wrongdoings were beyond those of mere mortals. Similarly exceptional were the rare heroes who enjoyed a happy existence in Elysium or on the Isles of the Blessed. They did so not on account of their virtuous behavior but because of their status and family connections with the gods.

References to the idea of moral judgment after death occur in poems and plays from the early fifth century bc, but the most fully articulated accounts of the afterlife survive mainly in the writings of philosophers. Drawing on abstract speculation as much as popular belief, Plato (about 428–347 bc) described separate destinations for the good and the bad, as well as cycles of penance and reincarnation. But for determining what the majority of ancient Greeks thought about the afterlife, his most revealing assertion may be that individuals dismiss the stories told about what goes on in Hades—until they face death themselves.

Envisaging the Underworld

The Greek Underworld was ill-defined as a place, although the approach to it often included a journey over water. The rivers of the realm are mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey (750–700 bc), but the poem otherwise presents Hades as a “murky darkness.” Centuries later, the comic playwright Aristophanes provided more color, describing wrongdoers lying in mud and dung, while initiates dance in myrtle groves (Frogs, 405 bc). But even at this date, there was little consensus about the Underworld’s geography. The philosopher Plato (about 428–347 bc) described four rivers in one account but omitted them from another.

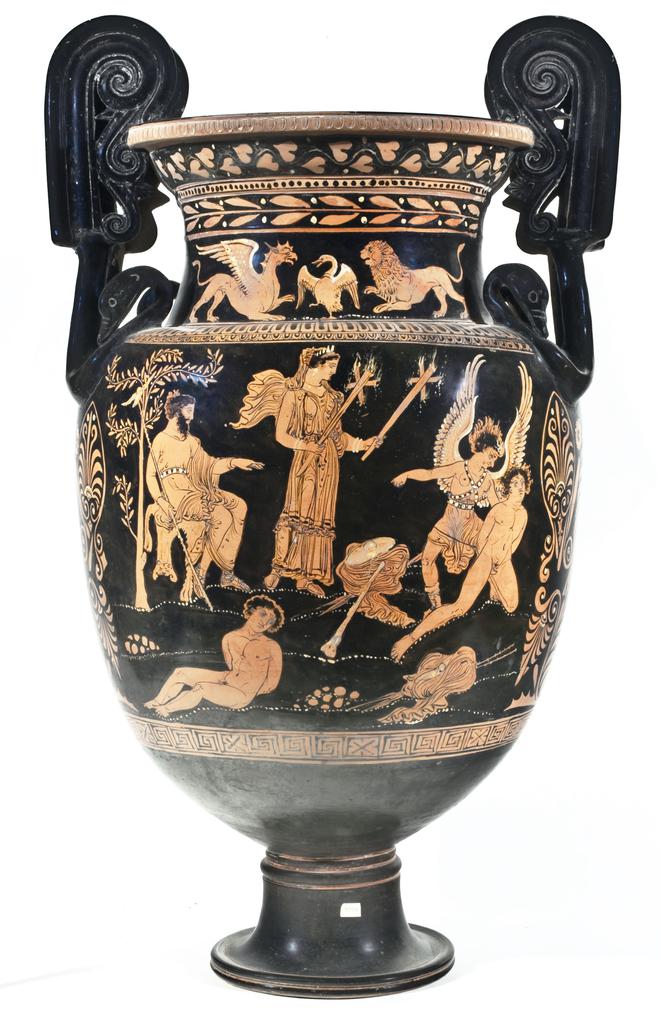

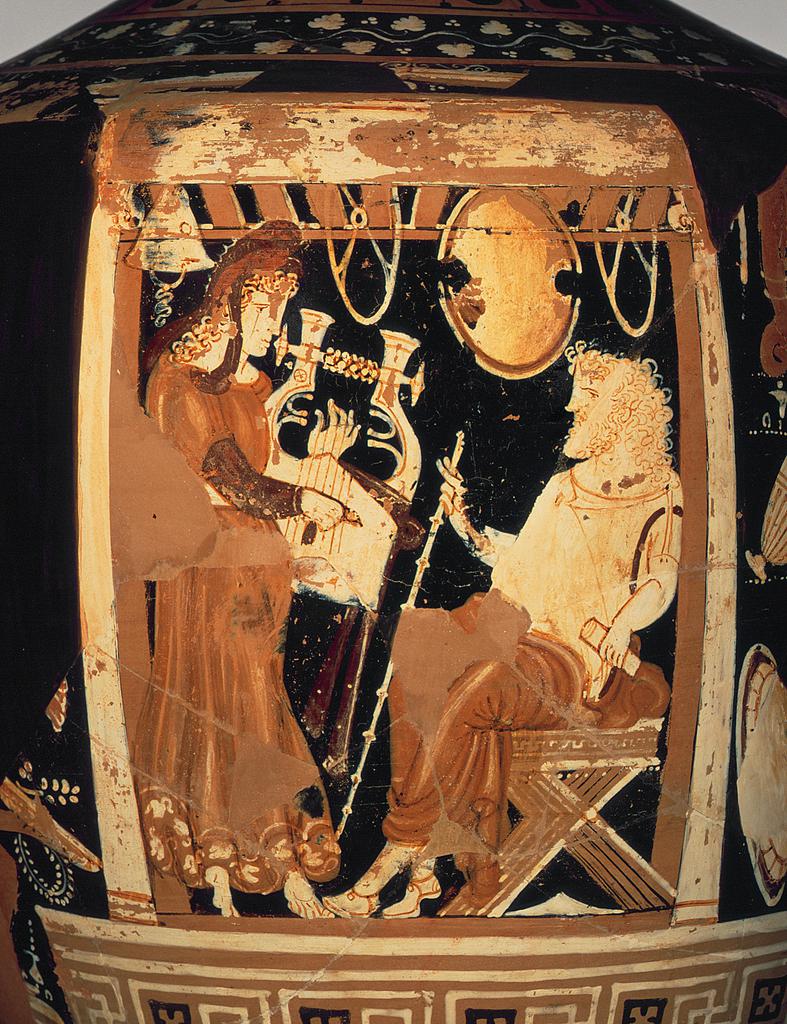

In Greek art the Underworld was an infrequent subject. In the sixth century bc, Athenian vase painters typically focused on individual inhabitants, such as Sisyphus rolling his rock. A famous fifth-century bc wall painting in Delphi depicted an Underworld landscape full of many characters, but it is only in South Italian vase painting from around 350 bc that a tradition of richly populated scenes developed. About forty Apulian funerary vessels, including the krater from Altamura, bear representations of the Underworld. Similarities among the compositions suggest that they derive from a shared model.

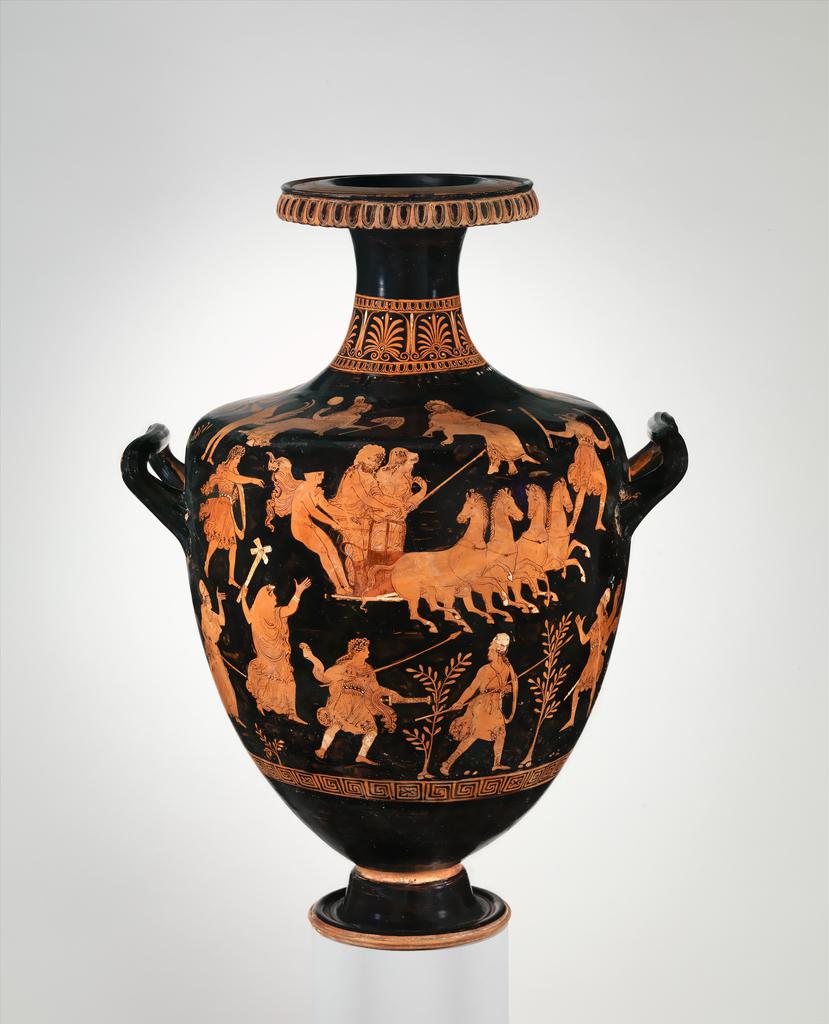

The Underworld Krater from Altamura

The Underworld krater was found in 1847 near Altamura in southeast Italy. The ancient name of the town is unknown, but by the fourth century bc it was one of the largest fortified settlements in the region. There is little information about what else was deposited with the krater, but its scale suggests that it came from the tomb of a prominent individual whose community had the resources to create and transport such a substantial vessel.

The inhabitants of southeast Italy—collectively known as Apulians—buried their dead with assemblages of pottery and other goods, and large vessels were produced for graves of the local elite. Though not Greek themselves, Apulians engaged closely with the culture of Greece, and many of their funerary vases are decorated with scenes from Greek myth and drama. No literary sources document Apulian views of the afterlife, but the Underworld krater from Altamura and other vessels like it suggest that Greek traditions were influential. Depictions of notorious wrongdoers, those who died young, and judges of the dead are all drawn from Greek mythology. Yet the practice of visualizing the Underworld so fully and the prominence accorded to Orpheus are distinctly Apulian approaches to imagining the afterlife.

The conservation and display of the krater from Altamura were made possible by support from the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Villa Council.

The Underworld Krater, up close:

Learn who's who in the Underworld

Mystery Cults and the Hope for a Better Afterlife

Faced with the thought of a bleak existence in the Underworld, some individuals sought to improve their lot. Virtuous behavior might not be sufficient, and one way to obtain a happier afterlife was thought to be through initiation in mystery cults associated with Orpheus and Dionysos.

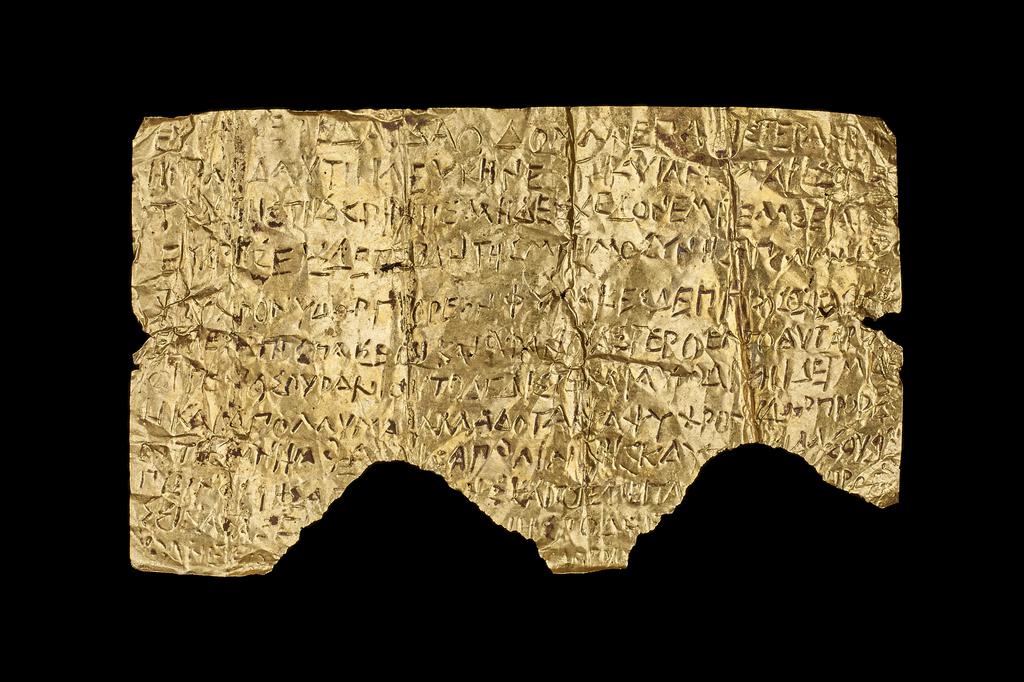

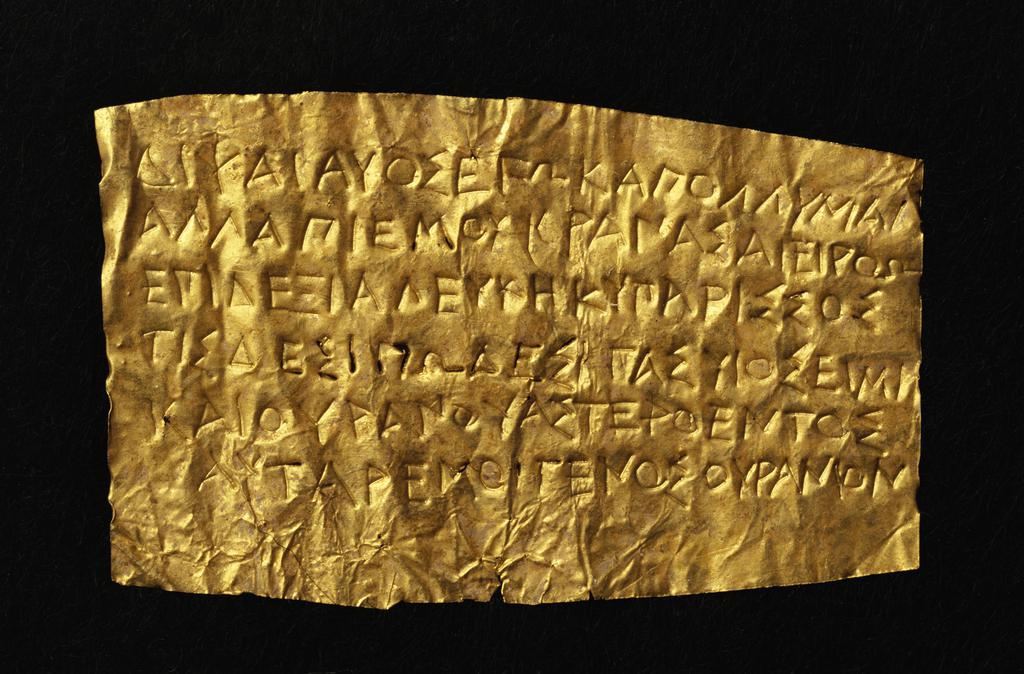

In contrast to public festivals and sacrifices, which were typically organized at a communal or civic level, the rituals of mystery cults were performed privately for individuals or small groups. Self-styled priests offered followers transformative experiences that mainstream practice could not provide and that marked the initiate as special. The rites were shrouded in secrecy and remain little understood today, but one of the most intriguing sources of information are the so-called Orphic tablets. Named by modern scholars after the mythical poet Orpheus, these are Greek inscriptions written on thin sheets of gold. They were deposited in graves, and usually bear a short text proclaiming the deceased’s distinguished status and providing guidance for his or her journey into the Underworld. Although the tablets have been found across a wide area—in Sicily and southern Italy, northern Greece, the Peloponnese, and Crete—they are exceedingly rare. Their owners were a select few who subscribed to beliefs that would have appeared esoteric and eclectic to their contemporaries.

The inscribed tablets vouch for those who had been initiated into mystery cults. The texts direct these privileged souls as they enter the Underworld. Some texts take the form of a dialogue, while others seem to speak on behalf of the dead individual. Their content varies, and many of them are riddled with scribal errors, but a number of phrases and themes recur.

Landmarks to look for in the Underworld are frequently mentioned. A path runs left or right of the house of Hades, and one must be careful to take the correct route. The track leads to a spring, often marked by a bright cypress tree, but typically this should be avoided. Though thirsty, the deceased must press on to the Lake of Memory. He or she may have to speak before unnamed guardians or in some cases the goddess of the Underworld, Persephone. The words to utter include claims of purity or divine origin. Other phrases allude to sources beyond our knowledge.

Space on these precious tablets was limited, and rather than describe the blissful existence that is the special preserve of the initiate, most texts focus on the journey. Nevertheless, there are occasional allusions to reincarnation, and some tablets promise the initiate heroic or even divine status in the afterlife.

Orpheus in the Underworld

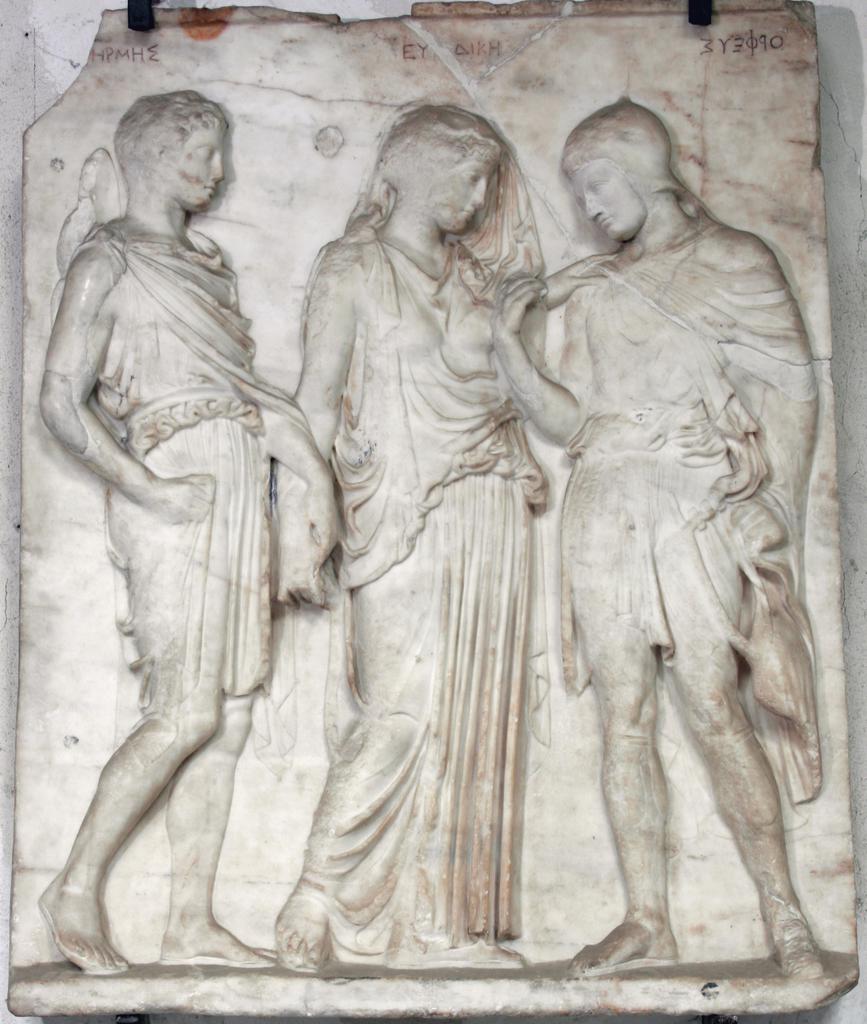

Orpheus was a mythical poet and singer of entrancing power. The son of a Muse and a king of Thrace—or, according to some, the god Apollo—he descended to the Underworld to recover his wife, Eurydike, after her early death. Through his musical prowess, Orpheus persuaded Hades and Persephone to restore Eurydike to life, only to lose her again when he disobeyed the gods’ instruction not to look back as they returned to the world above.

Despite this failure, Orpheus’s descent and return made him one of the few who could impart knowledge of the afterlife. He appears in a number of Underworld scenes on Apulian funerary vases playing his lyre before Hades and Persephone, and these images suggest safe passage into the unknown and the possibility of transcending death. Poems attributed to Orpheus, known today only from scattered references, probably recounted his journey into the Underworld. The so-called Orphic tablets, inscribed gold sheets instructing the deceased on where to go and what to say in the Underworld, may derive their authority from Orpheus’s special experience.

"Orphic" Beliefs

Whether there was ever a defined set of ancient beliefs and practices that should be termed “Orphism,” after the mythical singer Orpheus, is still debated. But even in the fifth century bc, unconventional ideas and habits were associated with him. In Euripides’s play Hippolytos (428 bc), Theseus ridicules his son’s strange behavior, saying, “Go on posturing . . . and revel with Orpheus as master, honoring the hot air of many books.” The heavy reliance on texts is a recurrent criticism, and the philosopher Plato referred dismissively in the Republic (mid- 370s bc) to “begging priests and seers [who] go to rich men’s doors . . . and produce a hubbub of books of Musaios [the legendary Athenian poet] and Orpheus.” Such itinerant priests, elsewhere called orpheotelestai (ritual initiators of Orpheus), taught that special rites guaranteed freedom from suffering in the afterlife. Those who participated in the rituals—and probably also made a financial contribution—obtained a level of spiritual purity that marked them out from the majority. In this way, they sought to allay their fear of what awaited them after death.

Sirens

The mythical Sirens were part-woman, part-bird. Their hybrid nature characterized them as marginal, otherworldly figures, existing between desire and terror, water and land, life and death. Like the legendary singer Orpheus, the Sirens had enchanting voices, but they used their vocal power to shipwreck mariners. Their fatally alluring song is described in Homer’s Odyssey (750–700 bc). Sailing past the bones of the Sirens’ victims on his journey back from Troy, the Greek hero Odysseus found an ingenious way to hear their song in safety. He tied himself to the ship’s mast and had his men fill their ears with wax so they would not be lured astray.

Over the centuries, the Sirens lost much of their dangerous aspect and became a recurring motif in Greek funerary art. Their song, though still linked with death, acquired mournful associations, rendering these figures exemplars of grief rather than danger. In Euripides’s play Helen (412 bc), the protagonist invokes the Sirens to “consort with me in my terrible griefs: as songsters harmonious with my lamentations send forth tears in accord with my tears, woes with my woes, and songs with my songs.”

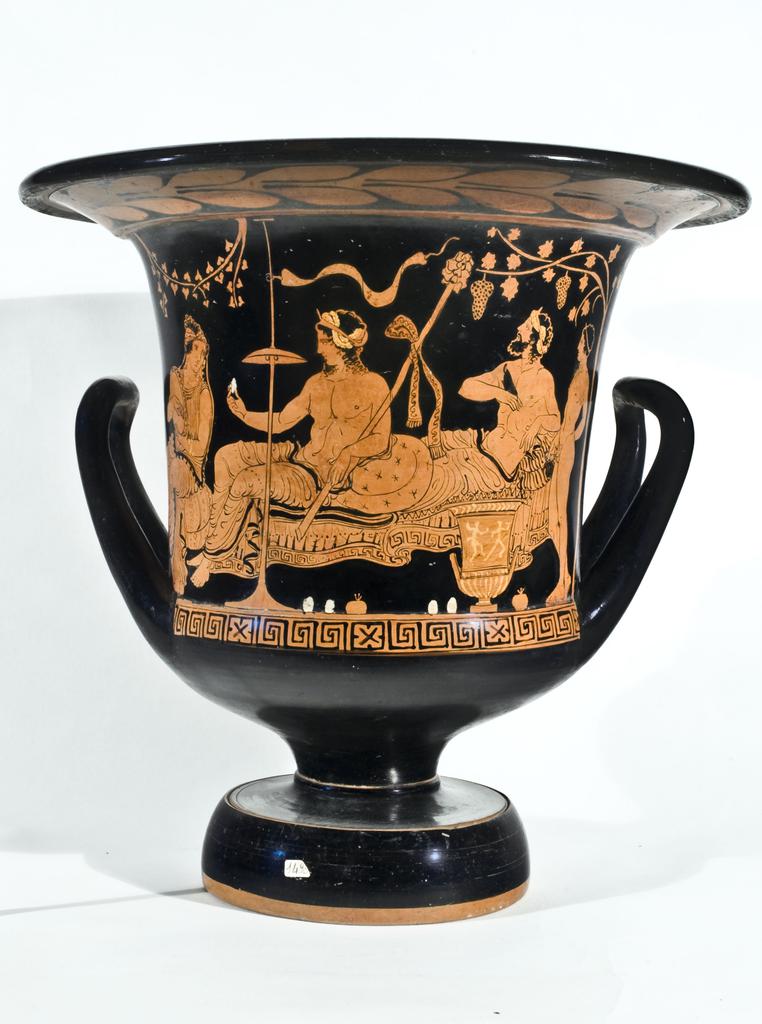

Paths to a Better Afterlife: Dionysos and Death

Dionysos is best known as the god of wine and theater, but in some circles, his power extended to the afterlife. Central to this belief was a story in which he was the son not of Semele, as was traditional, but of Persephone, goddess of the Underworld. Shortly after his birth, Dionysos was torn apart by the primordial Titans. Zeus, who was his father and king of the gods, retaliated by destroying them with thunderbolts, and Dionysos was re-created and born again. The first humans arose from the remains of the incinerated Titans and carried forever a trace of that monstrous crime. The only way mortals could purify themselves was through devotion to Dionysos, whereby they placated Persephone, who still lamented her son’s murder.

This narrative—perhaps only ever believed by a minority—may help explain the addresses to Persephone and claims to purity that recur on the gold tablets inscribed with instructions for the dead. Two examples in the shape of ivy leaves from a burial in north-central Greece make a connection with Dionysos especially clear: in both, the deceased is instructed, “Say to Persephone that Bacchios [i.e., Dionysos] himself has released you.”

"Wine as a Blessed Honor"

In the few Greek accounts that describe a blissful afterlife, the fleeting pleasures of this world—sweet fragrances, leisure, music, and dance—are imagined as extending forever into the hereafter. The blessed dead may even participate in an eternal banquet, a prospect that Plato ridiculed as a belief “that the highest reward for virtue is everlasting drunkenness” (Republic, mid-370s bc).

Scenes of symposia (male drinking parties) appear on many vases from southern Italy, often in funerary contexts, where they can be seen as expressions of hope about the afterlife. Dionysos and his entourage are occasionally present as well, blurring the boundaries between mortality and divinity.

Paths to a Better Afterlife: Hades, Persephone, and the Eleusinian Mysteries

When Hades, king of the Underworld, abducted Persephone, her mother Demeter, goddess of the harvest, traversed the world in search of her missing daughter. The fields became barren, and Hades was compelled to release the girl. But because he had tricked her into eating the seeds of a pomegranate while in the Underworld, she had to descend there for a third of each year.

In the Greek town of Eleusis, not far from Athens, where Demeter paused during her search for Persephone, an annual festival known as the Eleusinian Mysteries ensured participants good harvests and also a blessed afterlife. In contrast to private cults connected with Orpheus and Dionysos that promised their initiates a happy existence after death, the Eleusinian Mysteries were a central part of mainstream Greek religion. They were organized by the Athenian state and open to all Greek speakers save those who had committed murder. The rites themselves remained secret but likely included a reenactment of Demeter’s recovery of Persephone. The Greek writer Plutarch (about AD 46–after ad 119) described an initiation as a terrifying journey from shadow to light, akin to a near-death experience: “wanderings . . . through the darkness with suspicion, then before the very end, all the terrors—fright and trembling and sweating and amazement. But then one encounters an extraordinary light, and pure regions and meadows offer welcome.”